|

(click here to view the original post on Facebook)

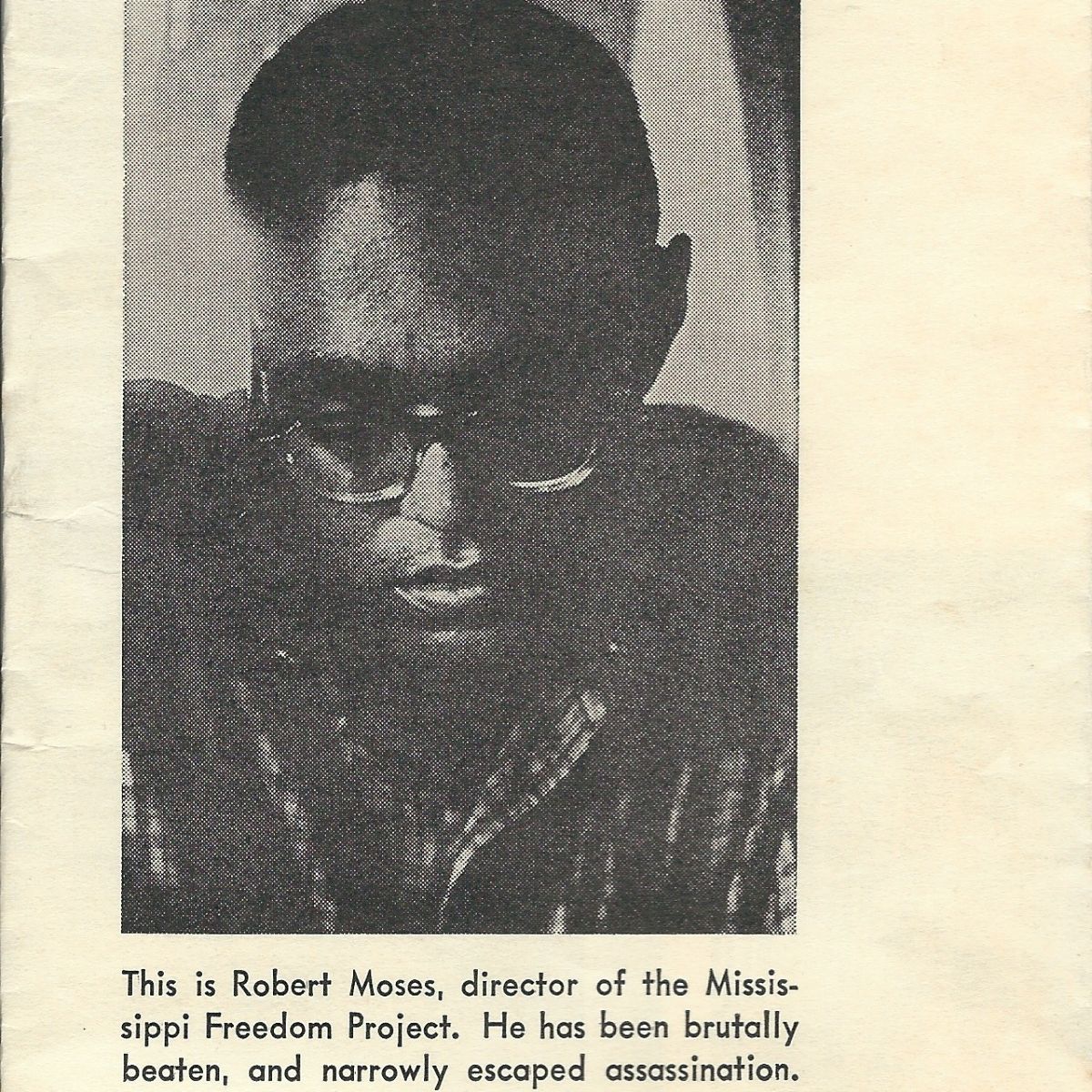

On this Week’s Peace of History: We direct our attention to Robert “Bob” Parris Moses: African-American civil rights activist, peace activist, public education advocate, and math literacy educator. Although a contemporary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the shape of Moses’ leadership style differed sharply from that of the more famous reverend. Where Dr. King’s leadership was based largely around his personal charisma on the national stage, Bob Moses avoided the limelight and preferred to foster grassroots, community-based movements. Despite the difference, however, Dr. King appreciated Moses’ experiments in nonviolent resistance, calling his “contribution to the freedom struggle in America” an “inspiration.” Born on January 23, 1935 in New York City, Moses showed himself to be very bright at a young age. Moses grew up in a housing project in Harlem and was one of only a handful of African-American students at the time who gained entry into Stuyvesant High School, the elite public school in Brooklyn. His experience receiving a top-rate education at a public school, while also witnessing the unequal opportunities for so many others in his community, left a profound influence on him. After graduating, Moses won a scholarship to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, and then earned a master’s degree in philosophy from Harvard University in 1957. His doctorate studies were cut short with the death of his mother and hospitalization of his father, but he returned to New York sometime later and worked as a math teacher at Horace Mann School. Moses’ entry into the civil rights movement began in the late 1950s, as the breadth of the struggle spread through the South and the news of the movement penetrated the North. In 1959, Moses volunteered in a minor capacity for the second Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., but organizers like Bayard Rustin encouraged him to do more. Upon Rustin’s suggestion, Moses traveled to Atlanta during his summer teaching break the following year, initially to volunteer for Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Once there, Moses volunteered with the still-nascent Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which shared an office with SCLC. Founded that April by students interested in doing nonviolent direct action, SNCC initially worked to desegregate lunch counters -- an effort that initially made Moses uncomfortable. He came around, however, when he realized that grassroots organizing meant that locals must follow “their own ideas, not mine.” Thus, he was sent by Ella Baker on a recruiting and outreach tour through the South. In Mississippi that summer, Moses met the local NAACP chapter president Amzie Moore. It was from Moore that Moses learned about black voter suppression south of the “Cotton Curtain,” and Moore who convinced Moses to return the next year. Bob Moses kept his word, returning to Mississippi in the summer of 1961 to volunteer for SNCC. That summer, Moses became the special field secretary for SNCC in McComb, Mississippi, and with NAACP member C.C. Bryant and other local community leaders began SNCC’s first voter registration campaign. Through the campaign, Moses and the other SNCC organizers learned of the immense untapped political energy of disenfranchised local people, and moreover, of the leadership already present in each community they worked in. This revelation was immensely influential to SNCC, and the group let this lesson shape their organizing style thenceforth. Moses and the other organizers would support and train up local community leaders and work closely with local activists like Fannie Lou Hamer to continue the work after outside SNCC organizers would leave. In Moses’ own words: “Leadership is there in the people. You don’t have to worry about where your leaders are, how are we going to get some leaders...If you go out and work with your people, then the leadership will emerge.” By the next year, Moses was named co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), the larger umbrella coalition of civil rights groups in the state. He was the main architect of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project of 1964, which brought student volunteers from across the United States to staff Freedom Schools, community centers, and door-to-door organizing for the re-enfranchisement of African-Americans in the state. When three of the volunteers went missing (their bodies found buried in an earthen dam by the FBI weeks later), many of the other student volunteers became frightened. According to first-hand accounts, Moses’ explicit acceptance of the mortal danger as a necessary risk to achieve their goals inspired all the other volunteers; everyone stayed. With that first challenge cleared, however, internal strife grew as the two white murder victims received the vast majority of media attention, while the murder of the black activist, as well as past black activist murder victims, did not get the same attention. At the same time, many volunteers were having difficulty accepting complete nonviolence as the best code of conduct for the movement. Bob Moses helped the diverse and at times distrustful members of the Project maintain their unity and commitment to the cause by letting the deaths of their comrades be a source of motivation, so that their sacrifices would not be in vain. By late 1964, after Freedom Summer and the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), Bob Moses resigned from his position of co-director of COFO, saying that his role in the organization had become “too strong, too central, so that people who did not need to, began to lean on me, to use me as a crutch.” Uncomfortable with the power he had accumulated, Moses stepped back from the civil rights movement and redirected his energies to the anti-war effort, even dropping his surname for his middle name for a while. In 1965, at one of the first major demonstrations in Washington, D.C. against the war in Vietnam, Moses was a featured speaker and drew comparisons between the racism underlying the war in Vietnam to the racism behind the murders of civil rights activists in Mississippi. In 1967, Bob Moses fled to Canada along with other young black men to avoid the military draft. Some took on the identities of Black Nova Scotians: primarily descendents of enslaved African-Americans who were either granted freedom by the British as “Black Loyalists” or who had escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad. Bob Moses lived there for two years before moving to Tanzania where he taught mathematics. He returned to the US in 1976 under the amnesty program for draft resisters. Today, Bob Moses is perhaps best known for his innovative Algebra Project, a national nonprofit that promotes quality public education and helps improve math literacy in children of poor communities. Throughout the decades, this humble man has continued in the struggle for justice in one form or another, and he continues to do so as his position as an educator. “Bob Moses.” https://snccdigital.org/people/bob-moses/ Intondi, Vincent J. African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement. Stanford University Press, 2015. “Moses, Robert Parris.” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/ency…/moses-robert-parris “Robert ‘Bob’ Moses.” http://freedom50.org/moses/ Visser-Maessen, Laura. Robert Parris Moses: A Life in Civil Rights and Leadership at the Grassroots. (click here to view the original post on Facebook)

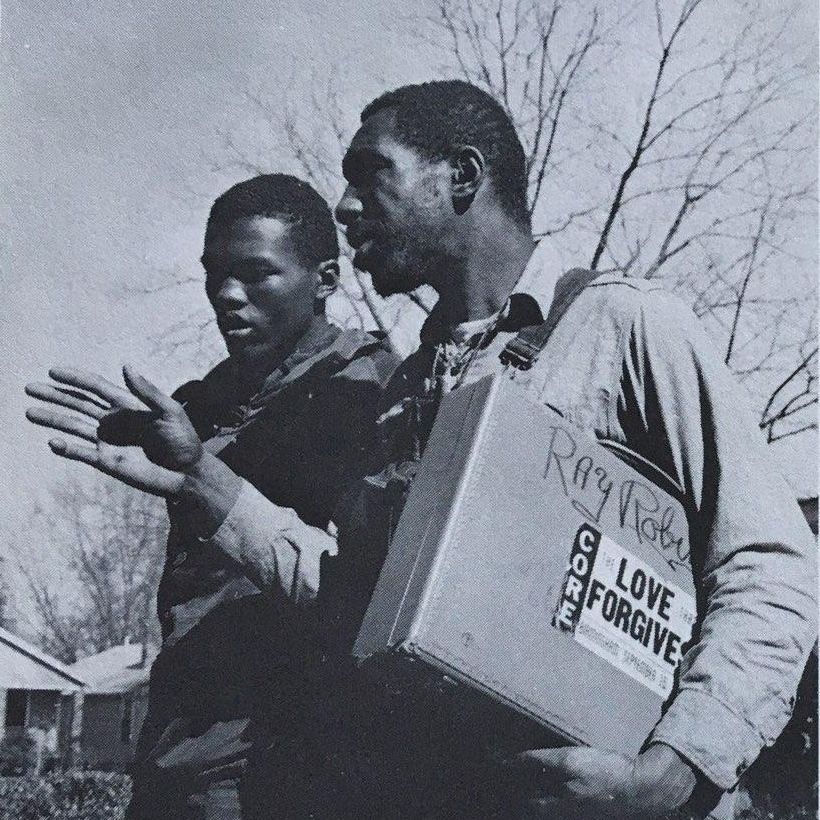

For this week’s Piece of History: We shine a light on the little-known peace and justice activist Ray Robinson. Born in Bogue Chitto, Alabama on September 12, 1937, Ray Robinson was a prize fighter before joining the peace and justice movements. Like Juanita and Wally Nelson, and many other African-Americans involved in the 20th century peace and justice movements, Ray is often characterized as a “civil rights” activist, but his work went well beyond black liberation in America. As his daughter Desiree Mark is quoted: “His whole thing was not black civil rights. It was human civil rights.” Ray attended the 1963 March on Washington, but one could argue that his fully active participation in the movement began later that year when he joined the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace organized by the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA). From Power of the People: “The purpose of the walk was to present to the Cuban people and their leaders the idea of nonviolent resistance and to protest the existence of the US naval base at Guantanamo.” From the beginning, however, the organizers had planned for the Walk to be racially integrated, and had expected to be challenged by citizens and law enforcement as they walked through the segregated South. Thus, the Quebec to Guantanamo Walk demonstrated nonviolent civil disobedience in practice, and promoted peace on the interpersonal, national, and international levels. Although not yet a “tried nonviolent activist” at the time he joined the Walk, Ray’s charisma, forthrightness, and audacity convinced Bradford Lyttle and other organizers to welcome him into the group. Ray was often described as a born leader, one who “put himself out in front of the project.” For example, while the other Walkers themselves were antiracist, many of them were still hesitant to openly challenge segregation in the South until Ray pointed out the hypocrisy of even entertaining the notion: “He wondered who was going to listen to us if we didn’t even feel free, ourselves, to behave naturally with one another” (Deming p. 75). Ray was tall, boisterous, and very visible, which sometimes made him a main target for segregationists. In Griffin, Georgia, after he and his fellow Walkers had been arrested for leafleting in a public park, the local police and a Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) agent used an electric cattle prodder on the walkers’ legs, genitals, spines, chests, and faces. Ray, however, was “particularly brutally tortured,” a pattern that would unfortunately repeat itself. The group was later arrested again in Albany, Georgia. There, Ray and several others went on a hunger strike to protest the conditions of the prison where they were incarcerated. Ray also attempted abstention from water multiple times. Chief Pritchett of the Albany Police Department had had a particular hatred for the Walkers, and especially for Ray Robinson. From Barbara Deming’s Prison Notes: “Ray has obsessed the Chief’s imagination from the start. He has, for one thing, been especially uncooperative -- even flipping himself off the stretcher as he was being carried into jail. Just the fact of his great physical strength and agility has obsessed the Chief, giving him hope of provoking him into using it to our discredit -- especially when he learned that Ray had once been a professional boxer…” (Deming p. 112). Pritchett attempted to break Ray’s fasts and provoke Ray’s aggression by a great range of physical and psychological tortures and threats, from beginning the process to transfer him to a mental asylum, to locking him in a “cell within [a] cell” where he could fit only if he “lay catercorner” (p. 107). There were more than a few times when Ray struggled with his own commitment to nonviolence under the injustice and torment of his incarceration. For example, at one point, Ray broke some shutters and a window in his overcrowded cell, and also pulled the toilet off the floor, in order to get medical attention for a sick but neglected African-American inmate. And yet, as Barbara Deming speculates, “Perhaps the very fact that Ray has to struggle with himself more than most to try to be nonviolent has made him especially real to a man like Pritchett.” Even as the Chief delighted in tormenting his prisoners, he was still known to deliver the handwritten notes that the prisoners would write to each other, including those of Ray. From Deming: “I remind myself, too, of the Chief’s surprising act upon Ray’s return -- when he brought around to my cell some writings Ray wanted me to see. Would he have been moved to such a gesture if, in the course of gaining his “victory” over Ray, Ray had not become for him the opposite of the grotesque stereotype the Chief liked to conjure up for us -- if he had not become for him a real person?” (Deming p. 115-116). Indeed, Ray had written a statement for Barbara Deming regarding the material damage he had caused in the prison, which Barbara then sent to the local paper. The text, more like a prayer than a legal statement, explained his personal growth and inner struggles regarding peace and nonviolence, and was widely circulated. Deming wrote: “I wonder now whether the words published in the Herald could have touched any of the paper’s readers in the white community. It doesn’t seem impossible to me… [An African-American woman Pritchett knew and respected] called him and read Ray’s statement to him over the telephone. Ray had now begun his first water fast… She told me that after she read Ray’s words to the Chief there was simply a long silence at the other end of the line. The Chief could usually find something to say, and it was her guess -- though it could only be a guess -- that he had been shaken.” (p. 114-115). After the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace, Ray continued his involvement in the peace and justice movements, participating in the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi, throwing in his support for Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1967, and helping to organize the Poor People’s Campaign’s Resurrection City at the Washington Mall in 1968, among many other activities. In 1973, while members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the FBI faced off at Wounded Knee at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, over the objections of his wife Cheryl, Ray Robinson traveled up to South Dakota to see what he could do to help reconcile the tense situation. Stories differ over what happened when Ray arrived at Pine Ridge, but most reports agree that he was shot by a Native man over a misunderstanding or what was perceived as insubordination. Anti-black prejudice may have played a factor, and some AIM members made it clear that Ray and other African-Americans were not wanted in “Indian Country.” Nevertheless, it appears that Ray’s last acts were guided by the pacifism and the faith in interracial peace he had begun to develop a decade earlier. Let us leave you this week with Ray’s statement from that Albany jail, that prayer that stunned his tormenter into silence: “Yes I was one of the angry young men, yes I rebel against society. I had no respect for law and order or man, especially the white man the one who has made me feel inferior… The most powerful weapon to me at the time being hatred, disrespect for anyone [white], I never trusted him, and every chance I got, I tried to hurt him… I was violence. I got at one point where I started waiting for one to assault me, where I could strike back with all my strength… I could not fight him legally, and win, so I decided to take up boxing where the world could watch and see me beat one with my hands… Revenge was what I thought I got… So now come a new thing to me that’s called nonviolence and I’m trying it. But yet my past of hatred for him has been stirred up again. Which way shall I go? It’s easy to go back to revenge, and God know I have all the rights… This thing that’s called nonviolence is the biggest challenge I have ever tried as a man and altho it’s hard, I have manage to continue to hold my violence in check. But how much longer can I stay this way? … Maybe more strength on my part will help. But really why should it be on my part, especially since I the oppressed. I’ll just leave things into God’s hands. But here I’m confused about God, where is he now? I need him now. But just when do God put his hand into this thing? … God … can’t you see just what I going thru as a young man? If I sound as tho I’m beginning to doubt you, God, if there’s one, show me your face, don’t keep hiding your face from me, don’t put words into others’ mouths to explain to me about you… But yet God I haven’t thrown you completely out of my mind. So give me strength and courage to continue onward to things unknown, who knows what the tomorrows will bring.” (Deming p. 112-113). Next week: we will tell the story of Bob Moses, an exceptional organizer and activist in the peace and civil rights movements. “A follower of Martin Luther King Jr. might be buried at Wounded Knee.” https://www.indiancountrynews.com/…/887-a-follower-of-marti… Cooney, Robert and Helen Michalowski (ed.). The Power of the People: Active Nonviolence in the United States. Peace Press. Deming, Barbara. Prison Notes. “Flash from Albany.” https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6312_cnva_albany2.pdf “Nonviolence and Police Brutality: A Document.” https://www.crmvet.org/info/quebec_guantanamo.pdf (click here to view the original post on Facebook)

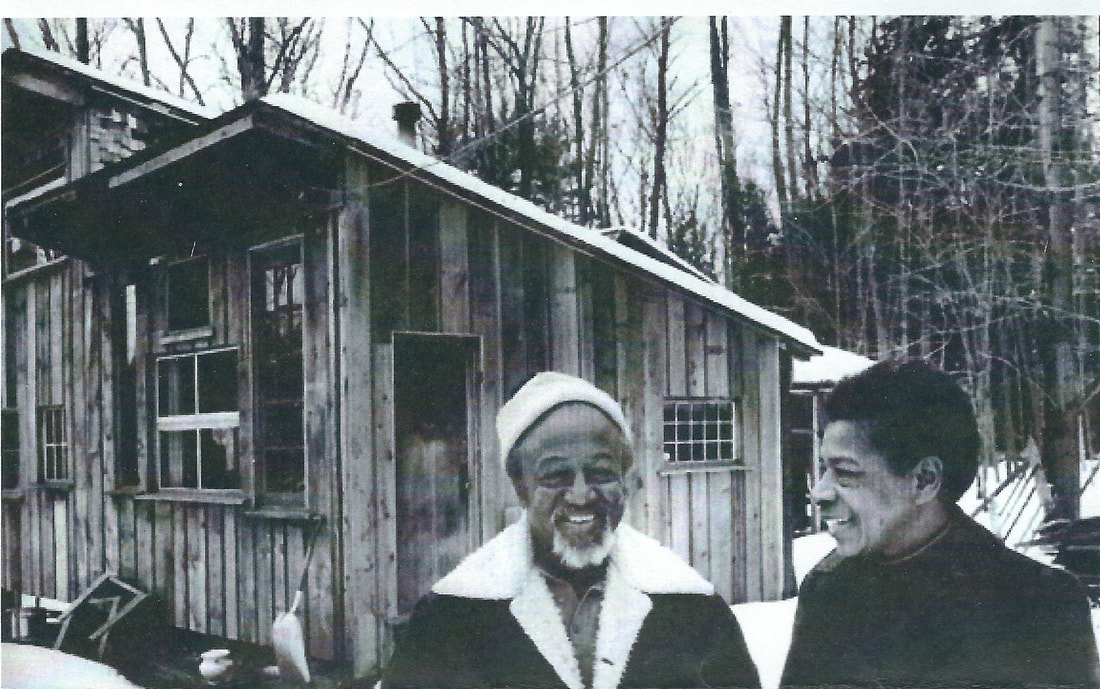

For this week's Peace of History: Let us continue honoring the legacies of Wally and Juanita Nelson. Last week, we surveyed some of the political movements, projects, and actions that carried Wally’s and Juanita’s respective brilliance across the country. This week, we will focus on how they lived as homesteaders in their later years, and how they influenced and inspired so many to live simply, happily, cooperatively, and consistently with pacifist values. We shall read some of the arguments the Nelsons themselves made in defense of their political convictions and their simplified lifestyle, as well as the words of friends, neighbors, and fans of these extraordinary individuals. Wally is quoted as saying: “Nonviolence is the constant awareness of the dignity and humanity of oneself and others; it seeks truth and justice; it renounces violence both in method and in attitude; it is a courageous acceptance of active love and goodwill as the instrument with which to overcome evil and transform both oneself and others. It is the willingness to undergo suffering rather than inflict it. It excludes retaliation and flight.” It is this expansive concept of nonviolence that proved to be a throughline in the lives of Wally and Juanita. In particular, the Nelsons’ belief in the “active love and goodwill as the instrument” for social transformation, as well as their “willingness to undergo suffering rather than inflict it” led to a successful radical rejection of the dominant economic system for decades. As US involvement in the Vietnam War escalated, in 1970, Wally and Juanita moved to Ojo Caliente, New Mexico to learn to be homesteaders. From Juanita’s memorial program: “...Juanita was intent on dissociating herself from an economic system that spawned injustice and war. She saw very clearly the connection between our modern lifestyles and war-making…Wally, who vowed he would never again have a hoe in his hand after the sharecropper days of his youth, needed some convincing. He could see, however, that Juanita’s vision of self-sufficiency was something totally different, and he acquiesced.” They learned to grow and preserve their own foods and live simply, with limited electricity and other “modern” amenities. In 1974, facing affordability issues, the couple relocated to Deerfield, Massachusetts upon the invitation of Randy Kehler and a Quaker-run school at Woolman Hill. There, with the help of old and new neighbors and friends, Juanita and Wally “...took apart and reassembled a cabin, had a well dug, and built an outhouse on the half-acre or so of land that the Woolman Hill community allowed them to use, as specified in a Memorandum of Understanding.” Despite -- or perhaps because of -- their extremely humble lifestyle, Wally and Juanita were known for their happiness and love for their fellow humans. Race had no meaning to them, except to mean the human race. Randy Kehler, long-time friend and neighbor of the Nelsons, said of Wally, “He showed us how to lead a life of integrity and how to have the courage of our convictions. He demonstrated that you can choose to live a different way and achieve a level of happiness most people can’t imagine. He was a very happy man.” And with Juanita, according to Ed Agro, “[E]ach conversation began and ended with hugs and smiles.” But their happiness did not necessarily mean they loved every part of their radical lifestyle. With clarity and humor, Juanita herself made reference to some of the sacrifices they’d had to make to follow what Wally referred to as “rightlivelihood” in a silly popular poem she wrote in New Mexico called “Outhouse Blues”: Well, I went out to the country to live the simple life, Get away from all that concrete and avoid some of that strife, Get off the backs of poor folks, stop supporting Uncle Sam In all that stuff he’s puttin’ down, like bombing Vietnam Oh, but it ain’t easy, ’specially on a chilly night When I beat it to the outhouse with my trusty dim flashlight -- The seat is absolutely frigid, not a BTU of heat… That’s when I think the simple life is not for us elite. Well, I try to grow my own food, competing with the bugs. I even make my own soap and my own ceramic mugs. I figure that the less I buy, the less I compromise With Standard Oil and ITT and those other gouging guys. Oh, but it ain’t easy to leave my cozy bed To make it with my flashlight to that air-conditioned shed When the seat’s so cold it takes away that freedom ecstasy, That’s when I fear the simple life maybe wasn’t meant for me. Well, I cook my food on a wood stove and heat with wood also, Though when my parents left the South I said, “This has got to go,” But I figure that the best way to say all folks are my kin Is try to live so I don’t take nobody’s pound of skin. Oh, but it ain’t easy, when it’s rainy and there’s mud To put on my old bathrobe and walk out in that crud; I look out through the open door and see a distant star And sometimes think this simple life is taking things too far. But then I get to thinkin’, if we’re ever gonna see The end of that old con game the change has got to start with me. Quit wheelin’ and quit dealin’ to be a leader in any band, And it appears the best way is to get back to the land. If I produce my own needs I know what’s goin’ down, I’m not quite so footsy with those Wall Street pimps in town. ’Cause let me tell you something, though it may not be good news, If some folks win you better know somebody’s got to lose. So I guess I’ll have to cast my lot with those who’re optin’ out. And even though on freezing nights I will have my naggin’ doubts, Long as I talk the line I do and spout my way out views I’ll keep on usin’ the outhouse and singin’ the outhouse blues. Inspirations to multiple generations of peace activists, Juanita and Wally were beloved by distant fans and their closest neighbors to the end. After Wally passed away, Juanita suffered a stroke in late 2010, at which point the community they had cultivated took action to take care of her. Let us end with the last part of Juanita’s memorial program: "[Many] opened their homes to Juanita and cared for her as a beloved member of their families for the last four years of her life. Many friends and acquaintances visited and supported her during this time. The love and steadfast commitment that Juanita extended to others during her long life circled back to embrace her: a beautiful ending to an extraordinary, well-lived, remarkable life.” Next week, we will take a look at Ray Robinson, a peace and civil rights activist who disappeared at Pine Ridge Reservation during the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee. “A Celebration of the Remarkable Life of Juanita Morrow Nelson" Long, Tom. “Wallace Nelson, 93, pacifist and early civil rights activist,” The Boston Globe. Nelson, Juanita. “Outhouse Blues” https://nwtrcc.org/juanita-nelson-remembrance-and-apprecia…/ (click here to view the original post on Facebook)

For this week’s Piece of History: We are celebrating Black History Month with stories of incredible yet under-acknowledged African-American activists in the modern peace movement. As we shall see, the history of the Voluntown Peace Trust overlaps with many of these important black peace activists. We begin with Wally and Juanita Morrow Nelson: civil rights activists, war tax resisters, and two of the co-founders of the Peacemakers -- one of the most quietly influential early peace organizations in modern United States history. Wally and Juanita Morrow Nelson were each impressive figures in their own right, and they inspired countless people with their personal examples of simple living and refusal to participate in an unjust economy. They were patrons of organic farms, supporters of community land trusts, promoters of simple and peaceful living, and teachers of nonviolence. Together, they are sometimes known as two of the “grandparents” of the modern war tax resistance movement. Wally Nelson was born in Arkansas in 1909 to a family of sharecroppers and a self-taught minister. After dropping out of high school to help support his family, he took a pledge of nonviolence with a Methodist youth group, which he tried to live by for the rest of his life. During WWII, Wally registered as one of 37,000 American conscientious objectors, but then walked out on the Civilian Public Service camp to which he was assigned, reasoning that his labor still contributed to the war effort. He and five others left for Detroit to work in service of a poor community there. He was later caught and incarcerated for three and half years, but never ceased his radical work, and in fact became an important figure in the desegregation of the federal prison system. It was in prison that Wally shared a cell with Chicagoan co-founder of CORE, Joe Guinn. It was also there that he met his future life-partner, Juanita Morrow, who was working as a reporter on prison conditions. In 1947, after leaving prison, Wally had participated in the Journey of Reconciliation rides sponsored by FOR and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the first “freedom rides” to test the 1946 Supreme Court decision to integrate interstate travel. Wally also became CORE’s first Field Secretary, effectively the national field organizer for workshops and actions in Washington D.C. and the country as a whole. Juanita Nelson was just as impressive and committed to the peace movement. Born on August 17, 1923, Juanita had always been a person of principle and action. In 1939, due to her own frustration at the indignity of segregated train cars, 16-year old Juanita decided in defiance to try sitting in every car of the train she was riding with her mother on their way to Georgia. She did so without incident, except for a black porter concerned for her safety advising her to return to her original car. Four years later, as a student at Howard University, Juanita and a few of her friends were arrested for ordering hot chocolate at a “whites-only” drugstore. Shortly after her night in jail, Juanita began working for CORE, helping to desegregate a restaurant at the edge of campus in less than a week. Leaving Howard early in part for financial reasons, she returned home and found work as a reporter for a local newspaper. In her new work, she met Wally Nelson while doing a story about segregation in the jail. After Wally left prison, he and Juanita began their lifelong partnership, joining the pacifist group the Peacemakers which had just formed. Their personal philosophies resonated with the group’s tenets of non-registration for the draft, war tax resistance, and nonviolence as a way of life. In 1950 they moved into an intentional community with other Peacemakers, including founders Ernest and Marion Bromley, in Cincinatti, Ohio. This caused tension among the neighbors, but this would not be the first time the Nelsons would defy the norm of segregation. The Peacemakers, founded in 1948, took their inspiration from Gandhi’s example in India and other experiments in nonviolent peace and liberation movements around the world. They also rejected the organizational principles of many other pacifist groups. Juanita Nelson, one of the co-founders, said, “Groups or cells are the real basis of the movement, for this is not an attempt to organize another pacifist membership organization, which one joins by signing a statement or paying a membership fee.” These cells were typically organized as intentional communities, so that individuals could work together to change their lives into ones consistent with radical pacifist values. The Peacemakers focused on small direct action projects and, starting in 1957, trainings in nonviolent action. Wally and Juanita had been giving nonviolent action trainings since the late 1940s, and so many of the Peacemakers’ trainings were personally led by Juanita and/or Wally Nelson, including the ones conducted in the summer of 1960 for the Polaris Action in New London, CT. The Peacemakers conducted numerous experiments in the complete integration of radical pacifism into one’s life, leading to a “living program” of draft and war tax resistance, personal transformation, and group participation in work to promote political and economic democracy. The group also initiated the first modern organized war tax resistance movement, and published the “Handbook on the Nonpayment of War Taxes.” Along with Ernest and Marion Bromley and Reverend Maurice (Mac) McCracken, Wally and Juanita Nelson are considered by many to be the grandparents of this movement. Decisions were made at an annual Continuation Committee meeting, and starting in 1949, The Peacemaker newsletter served as an important forum for letters, announcements, and personal accounts of radical pacifists for individuals and groups associated with the peace movement. For the first decade of its existence, up until the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA) was founded, the Peacemakers were the most active nonviolent direct action in the nation. Neither Juanita nor Wally ever wavered in their commitment to the pacifist movement. In 1957, Juanita and Wally briefly joined the radical pacifist Koinonia Farm in southwest Georgia to support their racial integration efforts. In an interview, Juanita recounted how Wally would take long trips to buy supplies for the farm when local businesses boycotted them for their integrated living policy. In 1959, Juanita was arrested in her home in Philadelphia for tax refusal. In contrast to many other activists of the time, who emphasized dignified, well-dressed appearances in the face of ugly violence and injustice, Juanita refused to change out of the bathrobe in which she had been arrested, saying, "Why am I going to jail? Why am I going to jail in a bathrobe? What does it matter in the scheme of things whether or not you put on your clothes? Are you not making, at best, a futile gesture, at worst, flinging yourself against something which does not exist? Is freedom more important than justice? Of what does freedom of the human spirit consist, that quality on which I place so much stress?" By one account, “Juanita Nelson was the first woman in modern times to be apprehended for war tax refusal,” although the government was never able to collect the money they claimed she owed. Continuing to experiment with ways to divest themselves from what they viewed as an unjust economy, the Nelsons began homesteading, first in New Mexico from 1970 to 1974, and then in New England for the rest of their lives, where they became deeply influential in the local community. They were frequent visitors to the CNVA / Voluntown Peace Trust as friends and valued resource people. From the home that they and many friends built, with an outhouse and no electricity, the Nelsons continued their work, helping found the Valley Community Land Trust, the Pioneer Valley War Tax Resisters, and the Greenfield Farmers’ Market. They supported the development of other community land trusts started by their friends Bob Swann and Chuck Matthei through the Institute of Community Economics and Equity Trust. For their lifelong work to promote peace and justice, both Wally and Juanita Nelson received the Courage of Conscience Award from The Peace Abbey in Sherborn, MA. Wally died at 93 on May 23, 2002. Juanita died on March 9, 2015 at age 91. Next week, we will continue with stories of African-Americans whose involvement in the peace movement has been woeful undertold. https://aaregistry.org/story/wally-nelson-a-committed-activist/ http://www.americancenturies.mass.edu/activities/oralhistory/nelson/index.html https://www.crmvet.org/mem/nelsonw.htm http://www.memorialhall.mass.edu/activities/oralhistory/nelson/bio.html https://web.archive.org/web/20090207195509/http://www.peaceabbey.org/awards/cocrecipientlist.html Cooney, Robert and Helen Michalowski (ed.). The Power of the People: Active Nonviolence in the United States. Peace Press. Gross, David (ed.) "We Won't Pay!: A Tax Resistance Reader." pp. 451-461 |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed