|

(click here to view the original post on Facebook)

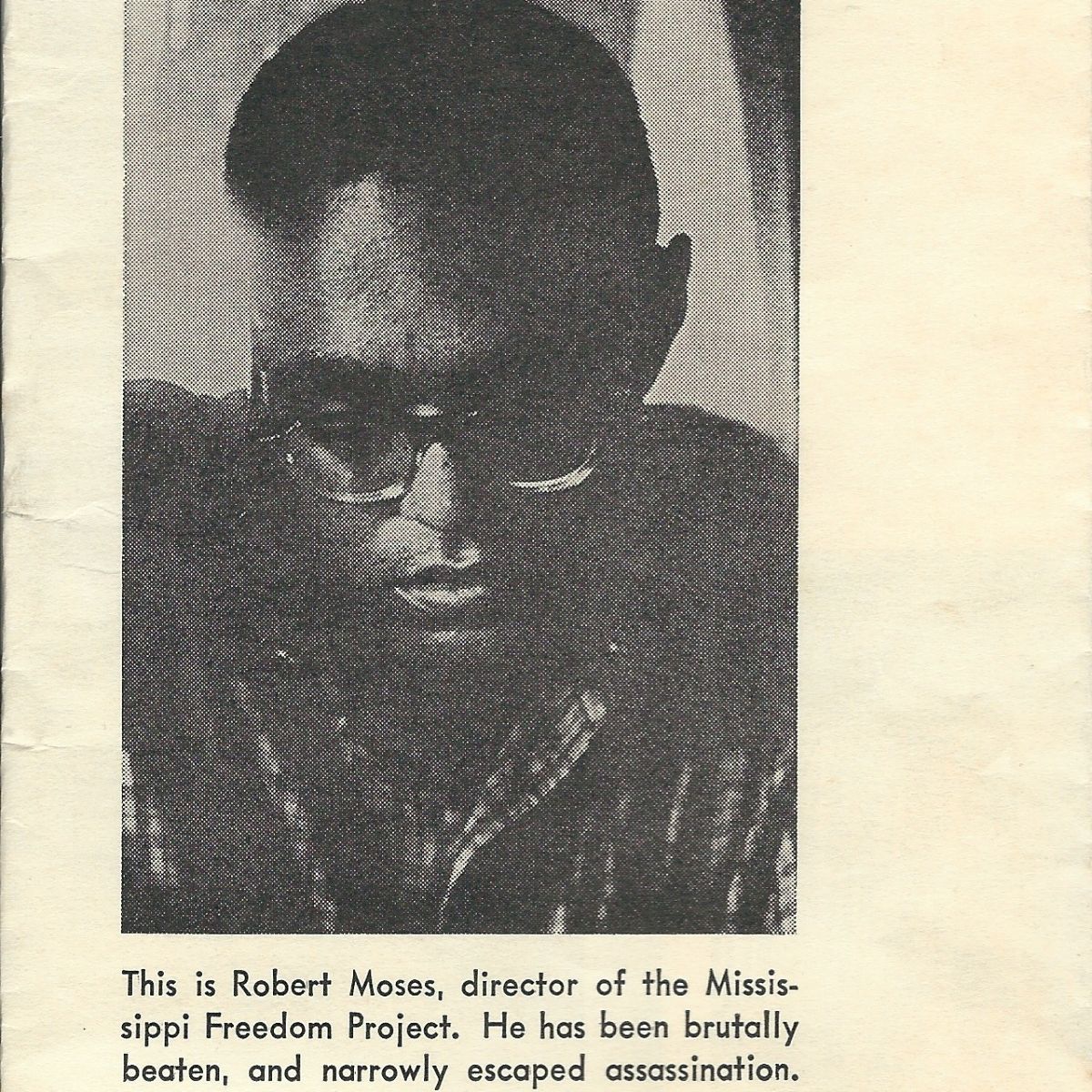

On this Week’s Peace of History: We direct our attention to Robert “Bob” Parris Moses: African-American civil rights activist, peace activist, public education advocate, and math literacy educator. Although a contemporary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the shape of Moses’ leadership style differed sharply from that of the more famous reverend. Where Dr. King’s leadership was based largely around his personal charisma on the national stage, Bob Moses avoided the limelight and preferred to foster grassroots, community-based movements. Despite the difference, however, Dr. King appreciated Moses’ experiments in nonviolent resistance, calling his “contribution to the freedom struggle in America” an “inspiration.” Born on January 23, 1935 in New York City, Moses showed himself to be very bright at a young age. Moses grew up in a housing project in Harlem and was one of only a handful of African-American students at the time who gained entry into Stuyvesant High School, the elite public school in Brooklyn. His experience receiving a top-rate education at a public school, while also witnessing the unequal opportunities for so many others in his community, left a profound influence on him. After graduating, Moses won a scholarship to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, and then earned a master’s degree in philosophy from Harvard University in 1957. His doctorate studies were cut short with the death of his mother and hospitalization of his father, but he returned to New York sometime later and worked as a math teacher at Horace Mann School. Moses’ entry into the civil rights movement began in the late 1950s, as the breadth of the struggle spread through the South and the news of the movement penetrated the North. In 1959, Moses volunteered in a minor capacity for the second Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., but organizers like Bayard Rustin encouraged him to do more. Upon Rustin’s suggestion, Moses traveled to Atlanta during his summer teaching break the following year, initially to volunteer for Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Once there, Moses volunteered with the still-nascent Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which shared an office with SCLC. Founded that April by students interested in doing nonviolent direct action, SNCC initially worked to desegregate lunch counters -- an effort that initially made Moses uncomfortable. He came around, however, when he realized that grassroots organizing meant that locals must follow “their own ideas, not mine.” Thus, he was sent by Ella Baker on a recruiting and outreach tour through the South. In Mississippi that summer, Moses met the local NAACP chapter president Amzie Moore. It was from Moore that Moses learned about black voter suppression south of the “Cotton Curtain,” and Moore who convinced Moses to return the next year. Bob Moses kept his word, returning to Mississippi in the summer of 1961 to volunteer for SNCC. That summer, Moses became the special field secretary for SNCC in McComb, Mississippi, and with NAACP member C.C. Bryant and other local community leaders began SNCC’s first voter registration campaign. Through the campaign, Moses and the other SNCC organizers learned of the immense untapped political energy of disenfranchised local people, and moreover, of the leadership already present in each community they worked in. This revelation was immensely influential to SNCC, and the group let this lesson shape their organizing style thenceforth. Moses and the other organizers would support and train up local community leaders and work closely with local activists like Fannie Lou Hamer to continue the work after outside SNCC organizers would leave. In Moses’ own words: “Leadership is there in the people. You don’t have to worry about where your leaders are, how are we going to get some leaders...If you go out and work with your people, then the leadership will emerge.” By the next year, Moses was named co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), the larger umbrella coalition of civil rights groups in the state. He was the main architect of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project of 1964, which brought student volunteers from across the United States to staff Freedom Schools, community centers, and door-to-door organizing for the re-enfranchisement of African-Americans in the state. When three of the volunteers went missing (their bodies found buried in an earthen dam by the FBI weeks later), many of the other student volunteers became frightened. According to first-hand accounts, Moses’ explicit acceptance of the mortal danger as a necessary risk to achieve their goals inspired all the other volunteers; everyone stayed. With that first challenge cleared, however, internal strife grew as the two white murder victims received the vast majority of media attention, while the murder of the black activist, as well as past black activist murder victims, did not get the same attention. At the same time, many volunteers were having difficulty accepting complete nonviolence as the best code of conduct for the movement. Bob Moses helped the diverse and at times distrustful members of the Project maintain their unity and commitment to the cause by letting the deaths of their comrades be a source of motivation, so that their sacrifices would not be in vain. By late 1964, after Freedom Summer and the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), Bob Moses resigned from his position of co-director of COFO, saying that his role in the organization had become “too strong, too central, so that people who did not need to, began to lean on me, to use me as a crutch.” Uncomfortable with the power he had accumulated, Moses stepped back from the civil rights movement and redirected his energies to the anti-war effort, even dropping his surname for his middle name for a while. In 1965, at one of the first major demonstrations in Washington, D.C. against the war in Vietnam, Moses was a featured speaker and drew comparisons between the racism underlying the war in Vietnam to the racism behind the murders of civil rights activists in Mississippi. In 1967, Bob Moses fled to Canada along with other young black men to avoid the military draft. Some took on the identities of Black Nova Scotians: primarily descendents of enslaved African-Americans who were either granted freedom by the British as “Black Loyalists” or who had escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad. Bob Moses lived there for two years before moving to Tanzania where he taught mathematics. He returned to the US in 1976 under the amnesty program for draft resisters. Today, Bob Moses is perhaps best known for his innovative Algebra Project, a national nonprofit that promotes quality public education and helps improve math literacy in children of poor communities. Throughout the decades, this humble man has continued in the struggle for justice in one form or another, and he continues to do so as his position as an educator. “Bob Moses.” https://snccdigital.org/people/bob-moses/ Intondi, Vincent J. African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement. Stanford University Press, 2015. “Moses, Robert Parris.” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/ency…/moses-robert-parris “Robert ‘Bob’ Moses.” http://freedom50.org/moses/ Visser-Maessen, Laura. Robert Parris Moses: A Life in Civil Rights and Leadership at the Grassroots. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed