|

(This week's post was written by VPT Board Chair Joanne Sheehan)

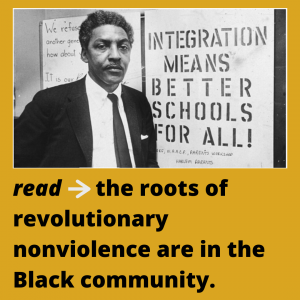

For those who have been reading A Peace of History, or know the history of the Voluntown Peace Trust, you will recognize a number of people in the history of the roots of revolutionary nonviolence (read the article here: https://www.warresisters.org/roots-revolutionary-nonviolence-united-states-are-black-community), which we hope you will read. The roots of VPT’s own history as the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) grew from roots in the Black community, the transnational solidarity with the anticolonial movement in India, and the solidarity of White allies who were radical pacifists. As described in the article, Bayard Rustin was one of the Black activists committed to the development of nonviolent action in the US in the late 1930’s. Bayard worked closely with A.J. Muste, a Dutch-born minister whose organizing went back to the Lawrence, Massachusetts strike of 1919. They shared a deep understanding of the importance of strategic nonviolent action and played key roles in spreading the use of nonviolence. They were both co-founders of the Committee for Nonviolent Action in 1957. The creation of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942 attracted Marjorie Schaeffer Swann, another CNVA co-founder. As Marian Mollin (who lived at Ahimsa Lodge at VPT) wrote in her book Radical Pacifism in Modern America: “CORE organized its campaigns around discipline and deliberation, always militant but never reckless or hasty. Marjorie Swann, a young white pacifist who joined Chicago CORE as a charter member, recalled that “any time you did anything...there were certain rules. Nobody could do anything, even picket, without getting the training!” CORE’s well-disciplined tactics and carefully planned protests were strikingly successful.” Nonviolence training was important to the preparation for action, and also helped deepen the understanding of nonviolent action. Wally Nelson and Juanita Morrow (Nelson), two Black activists involved in the early Civil Rights Movement, were both pioneers in the war tax resistance movement, nonviolence trainers, early CORE members, co-founders of the Peacemakers, and also worked closely with CNVA for decades. In 1947, sixteen Black and white men, mostly war resisters, participated in the Journey of Reconciliation, an integrated interstate bus ride that became the inspiration for the better-known Freedom Rides of 1961. Over half of the participants became active in CNVA. Polaris Action was organized by CNVA iIn the summer of 1960. Together with Peacemakers they organized a 16- day training in New London, CT. This brought together many of the people who had been actively developing nonviolence over the previous 20 years. Among the 24 listed as Faculty: Richard Gregg who wrote “The Power of Nonviolence” in the late thirties, co-founder of the Harlem Ashram Ralph Templin, Wally and Juanita Nelson and several others involved in war tax resistance, and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth from Birmingham, AL who was a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Barbara Deming came to the training as a skeptical journalist, stayed for the remainder of the training and became a committed nonviolent activist. In the mid 1970’s Marj Swann, who learned about nonviolence training in 1942 from CORE, and Bernard Lafayette who was one of the Nashville students trained by Rev. James Lawson in 1960, co-facilitated a “Training for Trainers in Boston. American Friends Service Committee staff person Suki Rice participated and went on to train the first Clamshell Alliance activists who occupied the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant in 1976, and helped design the participatory process and structure of nonviolent actions based on training and affinity groups. There are so many lessons that we can learn from these stories. We need to know and appreciate the history of nonviolent social change, particularly as so much of it was brought to us by Brown and Black people. As the movement today looks at how to center the people most affected by racial inequality and racial injustice and how to understand the role of white allies, we can learn from our Elders in the overlapping social movements of the 20th century. The lessons of solidarity, building trusting relationships, taking the time to learn skills through trainings, and developing strategy were, and remain, key to transforming society. Seventy-eight years ago today, President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 came into effect, forcibly moving an estimated 120,000 US residents of Japanese descent (most of whom were US citizens) out of their homes and jobs and into concentration camps for the remainder of the Second World War. While public opposition to this policy was scarce, some of the most vocal critics of the policy came from African-Americans, who more readily recognized the patterns of racial oppression -- Langston Hughes and George Schuyler were some of the most prominent critics of the time. But perhaps none wrote against Executive Order 9066 with more clarity and force than the columnist Erna P. Harris. Her example gives us a model for building alliances by recognizing patterns of our own oppression in others.

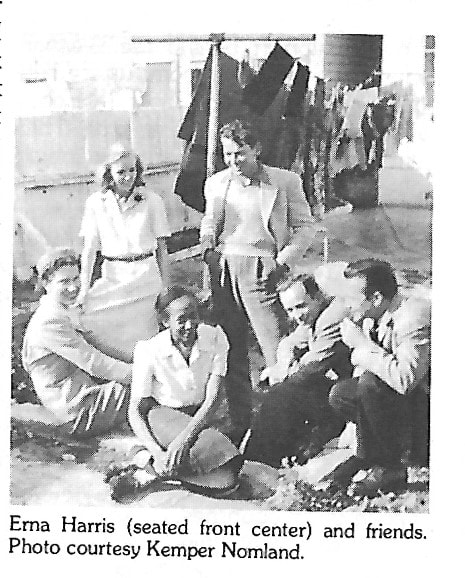

Born in segregated Oklahoma in 1908, Harris became one of the first African-American women to earn a journalism degree. Her father was an early American follower of Gandhi and was widely considered in his community as courageous and principled. Taking after her father, Erna not only struggled against the endemic prejudice in her area, but she also faced backlash when she argued against mandatory military conscription in her own weekly newspaper, The Kansas Journal. Harris was forced to close her newspaper due to her politics in 1941, and then moved to Los Angeles where she joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), an interfaith civil rights and social justice group, as well as the secular antiwar group the War Resisters League (WRL). About her experience with FOR and WRL, she later recounted: “We didn’t formalize it as a support group, but I was there taking my chances for going to prison… encouraging violation of the Selective Service Act and later when the guys were in the camp and some of them went over the hill from camps. A lot of them spent several nights on the floor in my living room in the apartment I rented with Ella, a German girlfriend. She and I had a little apartment and I would move out of my room and sleep back in her room so the COs could sleep on the floor in my room. They didn’t have any money and we were harboring criminals” (Harris, “US Women”). Erna also found a job with the Los Angeles Tribune, the youngest and most progressive of the three Black newspapers in the city. Now with a wider audience and some more support at her back, Erna began writing an editorial column around social issues, “Reflections in a Crackt Mirror.” Not long after she began writing for the Tribune, President Roosevelt made Executive Order 9066, and law enforcement began rounding up Japanese-Americans in 1942. It quickly became apparent that the Tribune was the only newspaper, Black- or White-run, in Los Angeles to formally oppose the order. Harris particularly went after the executive policy, writing periodically about the internment issue for the duration of the war. As law enforcement began to forcibly remove tens of thousands of people from their homes, Harris wrote in the Tribune, “[T]o visit evacuation neighborhoods and talk with neighbors of the ‘evil, treacherous, fifth column menaces’ who are being summarily moved away, who have been adjudged guilty without any trial at which to claim innocence was to acknowledge an event with all earmarks of a legalized community lynching” (Harris, “Reflections”). The use of the word “lynching” to describe the federal policy must have been intentional to draw the connection between Black and Japanese oppression. Indeed, in 1944, Harris wrote in her column, “Ever since the evacuation of Americans of Japanese ancestry and Japanese along the Pacific Coast was proposed, I have pointed out that the issue was one of race and on that basis affected anyone who was physically distinguishable as ‘colored’” (Harris, “Reflections”; emphasis added). Two years into the policy, it was becoming clearer to some that a failure to stand up against these injustices could mean an expansion of these kinds of policies to other groups as well. Harris began writing for other publications at the same time, working hard to connect other Americans to the plight of Japanese internment, but also to humanize Japanese-Americans on their own terms. After the Second World War was concluded, and tens of thousands of people were released from the camps, Harris continued to encourage interracial solidarity against White supremacy and White leadership, specifically encouraging Blacks to reject White-led “Brotherhood” initiatives and instead to form their own groups that “Nisei [second-generation Japanese-Americans], American Indians and other Americans whose physical characteristics make them detectable” could join and support. Harris’ persistent and clear stance against Japanese internment likely played a part in the newspaper’s decision to hire a bevy of excellent Japanese-American writers after the war. Thousands of African-Americans had moved into suddenly vacant neighborhoods during the war; now, many of the original Japanese-Americans were returning to their homes, only to find a new community already there. The Tribune sought to bridge the divide between the two communities. Until Harris’ departure from LA in the early 1950s to work more with the antiwar movement, this Black champion of Japanese-American rights worked with several Nisei individuals who would find renown as well: most notably, Hisaye Yamamoto, one of the best known Japanese-American writers of the post-war era. Yamamoto, in turn, would later become heavily involved in the antiwar and civil rights movements herself, joining FOR and communicating its activities to the Japanese-American community, as well as helping to organize the LA chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1947. For decades, Executive Order 9066 was largely forgotten in the collective American memory, but in part as a consequence of the civil rights movement, a new generation of Japanese-Americans began to organize and seek justice. The issue of Japanese internment only began to be redressed decades after the fact when Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which officially apologized for the inhumane treatment of Japanese-American citizens and made reparations payments to the survivors. The US Supreme Court only reversed the notorious 1944 decision in Korematsu v. United States (which upheld Executive 9066) three years ago in 2018, well after most of the victims had passed away. The State of California made its official apology for its role in the removal and internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII just last year in 2020. But even as recent lawmakers and justices patted themselves on their backs for these mostly symbolic acts of apology, the “Muslim ban” was still in effect and practically unchallenged, and ICE was still holding countless people including separated children in internment camps along the Southern border. As we now step into the next stage of the movement for Black lives, it is worth looking at how people built alliances in the past. Erna P. Harris’ showed us that alliance-building really begins with standing up for others -- and that such alliances can grow into movements that transform society. Sources: Cramer, Maria. “California Plans to Apologize to Japanese-Americans Over Internment.” New York Times. 18 February 2020. Ellen, Elster and Majken Jul Sorensen, Editors. “Women Conscientious Objectors: An Anthology.” War Resisters International, 2010. Hurwitz, Deena and Craig Simpson. “Against the Tide: Pacifist Resistance in the Second World War - An Oral Story.” War Resisters League Calendar, 1984. Robinson, Greg. “Erna P. Harris: An African-American Champion of Equality.” Discover Nikkei. 26 November 2019. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2019/11/26/erna-p-harris/ Robinson, Greg and Nichi Bei Weekly. “THE GREAT UNKNOWN AND THE UNKNOWN GREAT--The life and times of Hisaye Yamamoto: writer, activist, speaker.” Discover Nikkei. 14 March 2012. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2012/3/14/hisaye-yamamoto/ Today is the 54th anniversary of the passing of the illustrious A.J. Muste, perhaps the single most instrumental person in the 20th century US antiwar movement. At the end of his life,Muste. served as the National Secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), had a seat in the national committee for the War Resisters League (WRL), and worked as Chairman of the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA, predecessor to the Voluntown Peace Trust). CNVA published a Special Supplement on A.J. Muste. 1885 - 1967 from magazine WIN: Peace & Freedom Through Nonviolent Action, co-published by WRL. The following are excerpts from that special supplement, written by supporters and admirers: from a civil rights leader to a famous US presidential candidate, from one of the most well-known communist leaders in history to the president of a liberal arts college in Connecticut. The sheer range of people Muste personally affected should speak to his incredible ability to bridge differences and build alliances between such different kinds of people, and provides to us a model for changing society.

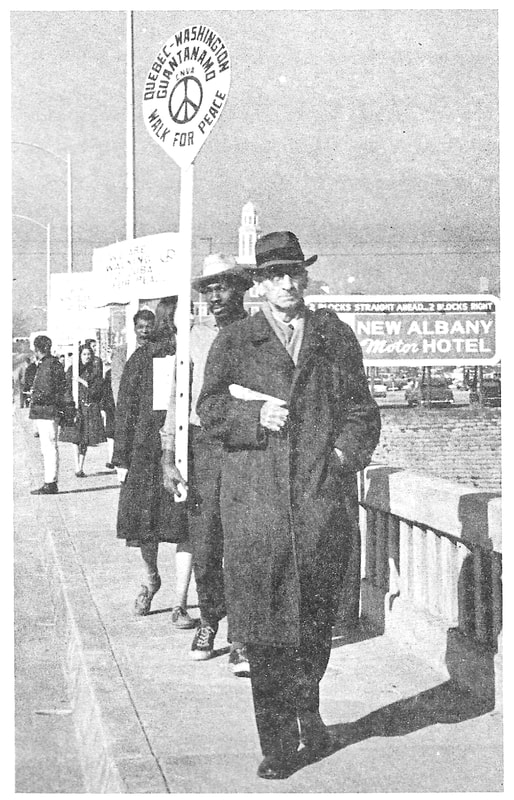

On A.J.’s importance to the antiwar movement: Neil Haworth, WIN editor, WRL member, CNVA activist “Those of us involved in the large peace demonstrations of the past few years, in which tens of thousands have marched and hundreds have volunteered for arrest, have a hard time remembering that such events have a very recent genesis. Just ten years ago, civil disobedience protests against militarism were the province of a mere handful of people. A.J. Muste has been the central figure of this growth. While a large number of conscientious objectors chose prison in World Wars I and II, the idea of pacifists actively confronting militarism on its own ground had its real start in the U.S. in 1957. As chairman of the group that became the Committee for Nonviolent Action, A.J. was frequently in the front line of the action and always present as major strategist, fund-raiser, and reconciler of differences. His work in this role has been absolutely vital in the development of a movement that has included conservative Quakers and other religious pacifists, angry young artists and Marxists, traditional liberals, and New Left students…” Bradford Lyttle, founder of the US Pacifist Party and organizer for WRL and CNVA “Polaris Action, launched the following summer [1960], stirred even greater controversy among pacifists than did Omaha Action. But in A.J.’s mind there seemed little doubt that Polaris Action could be an effort of high spiritual order and he backed it… A.J. stood by the San Francisco to Moscow Walk, too. He negotiated tirelessly with Peace Committee officials in the Communist countries… It came to me [last fall] that none combined a greater number of virtues than did A.J. It was an odd but inescapable fact that the tall, stooping, quivering, compassionate gentleman who worked in the office across the way had become the greatest man in the world…” On A.J.’s physical and moral courage: Barbara Deming, journalist, WRL member, CNVA activist: “It was during the trip (to Vietnam) that five of us made with him last April to protest the war in Saigon. On the last day of that trip, when we tried actually to make our protest, I was very scared for A.J., as well as for myself. For one thing, we had decided not to cooperate with Ky’s police when they arrested us; they would have to carry or drag us. None of us had any idea how rough they might be; and A.J. looked so very frail. As it turned out they were gentle with us, but up to the last moment of course one was never sure that the next official to handle us would be gentle.” Ho Chi Minh, President of North Vietnam at the time (by telegram): “OUTSTANDING FIGHTER FOR PEACE AND DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENT IN USA AND WORLD” Robert F. Kennedy, US Senator at the time and future US Presidential candidate (by telegram): “A.J. MUSTE SPOKE TO ALL GENERATIONS BUT WAS LIMITED BY NONE. HIS COURAGE WAS BOTH MORAL AND PHYSICAL NOT ONLY IN HIS WILLINGNESS TO FACE IMMEDIATE DANGERS BUT MORAL AND PHYSICAL NOT ONLY IN HIS WILLINGNESS TO FACE IMMEDIATE DANGERS BUT ALSO THAT FAR MORE RARE WILLINGNESS TO OPPOSE HIS SINGLE CONSCIENCE TO THE OPINIONS OF HIS FELLOWS IN THE PURSUIT OF HIS IDEALS AND IN THE SERVICE OF US ALL. HE WAS ALWAYS READY TO TAKE THE FIRST STEP, THE NEXT STEP, OR THE LAST STEP.” On knowing A.J. and his legacy Gordon Chistiansen, WIN editor, WRL member, CNVA activist: “Liberalism responds in strange ways when it bumps into radical pacifism. I encounter these extraordinary responses all the time here in New London, Connecticut. But what I’m thinking about right now are some reactions to A.J. Muste along about 1960 when Polaris Action was just beginning to bite into this community… [Connecticut College President Rosemary Park] was saying that to truly know A.J. Muste is, in a way, tragic; to actually grasp and accept what is being said by that skinny Dutchman-preacher turned pacifist-revolutionary, whose face and words and actions could bore so gently but so irresistably [sic] into your conscience, is to lose control of your own destiny. When all that happens to you, the events, or the fates, or principles take over and your life moves inexorably toward… well, toward something. So far the judgment is a wise one; I believe that is what happens to anyone who is really touched by A.J. But the liberal goes on to structure it as a true tragedy by concluding that that “something” toward which the Muste-touched radical moves so inevitably is somber, unhappy, disastrous. He believes that dedication to the proposition that human beings should love one another and deal nonviolently with each other is fatal utopianism. Here finally, is the tragedy of knowing A.J. It leads inevitably to the death of a liberal and to the destruction of cherished liberal standards. It is simply not possible, after once having been truly a part of A.J.’s life, to have an isolated, uninvolved life of one’s own. The radical tragedy comes if a person touched by A.J. tries to deny that knowledge and go back to being a conventional, establishment liberal; he is doomed to a life of denial, and he must live with the knowledge of his own denial. The tragic liberal judgement [sic] sees this denial of radical pacifist vision as the only alternative. He cannot understand the joy and freedom and fullness of a life of resistance to a violent, unloving system. Hence the liberal’s tragic judgment of A.J.’s vision.” Barbara Deming, journalist and WRL member, CNVA activist: “I have sat with him at so very many committee meetings, where after hours it was easy to become dazed by our own endless words about this or that program of action which we might or might not adopt, and easy somehow to forget in the process the realities of the particular situation with which we were supposed to be concerned. And time after time I have seen A.J. at a certain point speak out of his own suddenly renewed sense of that situation, his sharp sense of the real people involved to whom real things were happening. And because it was real to him as he spoke, it would suddenly be real again to everyone in the room.” James Bevel, Civil Rights activist since Nashville Lunch Counter Sit-in, Director of Spring Mobilization Committee to end the War in Vietnam (a role which A.J. Muste asked Bevel to take shortly before his death) “We say A.J. is dead and the tragedy is that most of us don’t understand the process of life. We say A.J. is dead but anybody who was caught up in the process of bringing people together can never die.” Source: Reyes, Gwen, editor. WIN: Peace & Freedom Through Nonviolent Action, Special Supplement: A.J. Muste 1885-1967, 1967. February is Black History Month, and today marks the 108th anniversary of the birth of Rosa Parks. Famously, on December 1, 1955, Parks became the catalyst of the Montgomery Bus Boycott after refusing to move to the “colored” section in the back of a public bus. What is less well known, however, is that Parks was already involved in civil rights and antiracist activism when she committed her act of civil disobedience.

In 1932, Rosa married Raymond Parks, an active NAACP member. Seeing the difficulty of her husband’s work started to radicalize Rosa to the fight for racial justice. In 1943, Rosa Parks officially joined the NAACP and started working as secretary for the president of the Montgomery chapter, Edgar Nixon. That same year, defying Jim Crow and all of its attending laws meant to keep her from doing so, Rosa began attempting to register to vote. On one of her first attempts to register, Rosa had a run-in with the notoriously racist bus driver James F. Blake, who kicked her off the bus for entering through the front “Whites” stairwell as opposed to the back. One must wonder if Blake’s treatment made Rosa even more committed to racial justice. Her voter registration was finally approved two years later, in 1945. Over the next decade, Rosa and her husband Raymond would continue to work in the civil rights movement. Rosa began leading the NAACP Youth Council, and reformed it in 1954 to take greater stands against segregation. During this time, Virginia and Clifford Durr, a White liberal couple for whom she worked as a seamstress, encouraged Rosa to attend courses at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Clifford was on the Highlander board of directors, and thus helped Rosa fund her travel and stay at the school in the summer of 1955. Inspired by the successful folk schools in Denmark, the Highlander Folk School had been established during the Great Depression in 1932 “to provide an educational center in the South for the training of rural and industrial leaders, and for the conservation and enrichment of the indigenous cultural values of the mountains” (Horton and Freire). It was one of the only racially integrated schools in the South, and despite being the target of persistent racist violence since at least the 1950s (the central office building was torched by arsonists as recently as in 2019), the school came to be affiliated with several civil rights leaders: Dr. King, John Lewis, Rosa Parks, Julian Bond, and more. One of the most important people at the Highlander Folk School was Septima Clark, a Black former school teacher who had lost her old job due to her activity in the civil rights movement. While Clark was attending her first workshop, Highlander founder Myles Horton was so impressed that he hired her soon after as the full-time director of workshops. That summer in 1955, a year after the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education decision was made that federally mandated the desegregation of public schools, Rosa took Septima Clark’s two-week workshop, “Racial Desegregation: Implementing the Supreme Court Decision.” By all accounts, Rosa was quiet and not particularly optimistic about positive change coming to Montgomery, which she described as “complacent.” Nevertheless, the glimpse Rosa received at Highlander of a harmonious and racially integrated future transformed her. Rosa was particularly inspired by Septima Clark’s example: her personal story of losing her career and risking so much else to continue in the movement for civil rights, only to end up at Highlander as a director and equal to White men in the organization. Rosa left Tennessee with some reluctance but with a redoubled conviction, promising to continue working with the NAACP Youth Council for desegregation. Five months after she had returned to Montgomery, a bus driver demanded Rosa that she give up her seat for White passengers. The driver was none other than James F. Blake, the man who kicked Rosa off the bus 12 years earlier. This time, Rosa refused; when Blake threatened to call the police, she responded, “You may do that.” That night, Edgar Nixon and Clifford Durr bailed her out. Within days, Nixon and the NAACP, led by the Women’s Political Council, had begun organizing a boycott of the Montgomery bus system in Rosa’s defense: a campaign that lasted over a year and which became one of the first major groundbreaking events in the history of civil rights. A few years later, when the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) bought the “Peace Farm” in Voluntown, predecessor to the Voluntown Peace Trust (VPT), the Highlander Center was one of their major inspirations. Like at Highlander, the CNVA ran community citizenship and activist training workshops from its founding in 1962. Indeed, some of the founding members of the New England CNVA attended courses at Highlander Folk School, and later VPT members have taken workshops at its successor, the Highlander Center, as recently as in the past decade. The Voluntown Peace Trust continued this tradition of community folk education, hosting workshops and other events through the past couple decades: nonviolence training weekends, YouthPeace weekend retreats for high school students, and more. Last year, as the movement for Black lives gained momentum after the murder of George Floyd, VPT started running training workshops online for people wanting to get involved with racial justice in Connecticut. Another run of VPT workshops for 2021 is in the planning stages now. The Highlander Folk School showed Rosa Parks a vision for a better world and inspired her to assert her rights in “the cradle of the Confederacy.” Five months later in Montgomery, Rosa sparked one of the most foundational campaigns in the civil rights movement. As a fellow folk learning center, VPT seeks to do the same for eastern Connecticut and New England as a whole. Sources: Horton, Myles and Paulo Freire. We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Temple University Press, 1990. Robnett, Belinda. How Long? How Long? African-American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights. Oxford University Press, 1997. Theoharis, Jeanne. The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. Beacon Press, 2013. Whitaker, Matthew C. Icons of Black America: Breaking Barriers and Crossing Boundaries. ABC-CLIO, 2011. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed