|

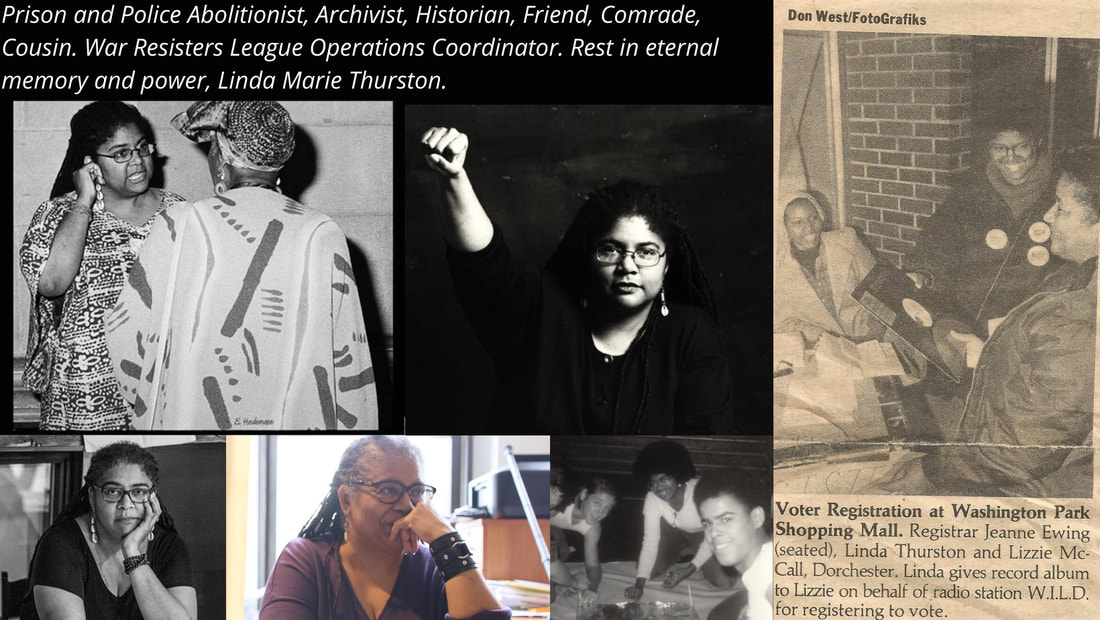

For this week's A Peace of History, we are sharing this memorial post honoring Linda Thurston, who unexpectedly passed away last weekend. Linda was a dedicated police & prison abolitionist and Operations Coordinator for our friends at War Resisters League. As a WRL staffperson, Linda stayed at VPT numerous times for retreats, national committee meetings, and more. As an historical archivist, Linda also advised us invaluably on what to keep and preserve from the many documents of Marj Swann. As we share some staff with WRL, Linda's passing comes as a shock to many in our community who worked closely with her for many years. Please be patient with us as we at VPT process this tragedy and work through how to move forward. Linda's family has organized a HomeGoing fundraiser to cover the funerary expenses. If you can give to ease some of the financial burden for the family of this amazing woman who gave so much of herself to social justice causes, please visit the following address: https://www.gofundme.com/f/homegoing-for-linda-m-thurston... To our dear community,

We are grieved to be sharing with you all devastating news: Linda Thurston, War Resisters League's Operations Coordinator passed away unexpectedly this weekend. Linda first organized with WRL for the Day Without the Pentagon action in 1998 and later joined the national staff collective in 2007 where she was responsible for maintaining daily operations, our office space, the website, technology, and was known to geek out about tech things. She held much WRL history and institutional knowledge. Linda leaves a big void in our hearts. Linda dedicated her life to movement and radical antiwar politics, particularly prison and police abolition ("before it was cool," she would often say ❤️). She fought tirelessly to end the death penalty and wrote to many political prisoners over the decades. In addition to being an abolitionist, Linda was many things: archivist, historian, radio host, Star Trek nerd. As we organize in memory of Linda, we want to invite you to share the memories of the Linda you knew and the pictures you have of her. Leave them publicly in the comments here, or reply back to this email. There will be more information regarding a memorial, which we will share with you soon. In grief and love and solidarity, War Resisters League On May 21, 1956, the United States performed its first air drop of a thermonuclear (hydrogen) bomb. While the Soviet Union accomplished a similar feat the year before with a fraction of the payload, the success of the U.S. test touched off a new chapter in the nuclear arms race. But that historic and consequential test was just one of 23 nuclear weapons tests that the United States performed over 8 years at and around Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. In honor of Asian-American / Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we offer a brief overview of U.S. nuclear weapons testing at Bikini Atoll, the fallout caused by the tests, and the trauma inflicted on the local people that persists to this day.

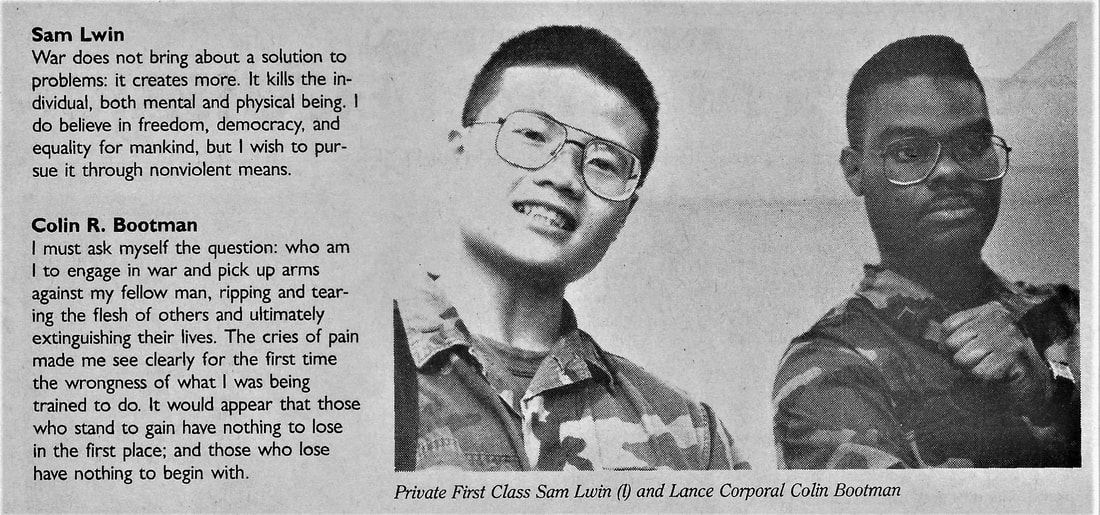

The tests that made up Operation Crossroads were decided in early 1946, just a few months after the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The weapons used were atomic bombs similar in scale to the ones used on Japan. The 167 Bikini Atoll inhabitants were told of the decision after the fact, and were convinced by U.S. Army officials to temporarily evacuate the atoll to the uninhabited Rongerik Atoll 120 miles away. The Bikinians soon found that the new atoll could not be adequately farmed, but it was not until anthropologist Leonard E. Mason visited Rongerik Atoll in January 1948 that the U.S. government realized the Bikinians were starving. By then, the United States had completed two weapons tests but canceled the third due to the overwhelming radioactive contamination of the area from the first two. The Bikinians could not return. Testing resumed in 1954 with Operation Castle, a series of experiments to test designs for new thermonuclear (hydrogen) bombs many times more powerful than the ones used on Japan. This series began with the now-infamous Castle Bravo test, the largest nuclear explosion the United States has ever caused. The blast was twice as powerful as scientists had predicted, completely vaporizing three islands, and produced enormous amounts of radioactive fallout that spread across the Marshall Islands and fell upon the people living there, including the displaced Bikinians on Rongerik Atoll. Over a thousand people ultimately came down with symptoms for acute radiation syndrome, and one Japanese fisherman died as a direct result, causing an international public outcry. But testing continued through the rest of 1954. Two years later, the United States started a new round of tests under the name Operation Redwing, including one specifically ordered by the Department of Defense to intimidate the Soviet Union: Operation Redwing Cherokee. This was the only test of the series not expressly for weapon development, and the first time the United States had successfully detonated a thermonuclear weapon dropped from a plane, demonstrating to Soviet rivals the U.S. capability to deliver such a weapon in war. All the tests in the Redwing series were named for Indigenous American nations -- following the longstanding American tradition of claiming and militarizing Indigenous names. Despite being dropped 4 miles off-course, the United States made its point. The Soviet Union, however, responded with an acceleration of their nuclear weapons program that would not slow for several more years. While the literal nuclear fallout from the tests irradiated the islands, the metaphorical fallout came in the form of an international public outcry to end all such nuclear tests forever. As the destructive power of these weapons increased, and as the influence of the anti-nuclear movement in the United States grew, it became clear that the arms race would likely only end in one of two ways: disarmament or death. Then, the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 brought the world to the brink of nuclear war, forcing many on both the U.S. and Soviet sides to reevaluate the international strategies they had been pursuing. Thus, in 1963, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty prohibiting the vast majority of nuclear weapons tests and significantly slowing the arms race. In the decades since, Bikinians have made a few attempts to resettle their old home, but have suffered severe effects from the radioactive contaminants as a result and were forced to evacuate. Although some studies suggest that human habitation is now possible on Bikini Atoll, because the radiation has worked itself into the ecology over the ensuing decades, no food grown or caught there is safe to eat. Just a handful of people live on Bikini Atoll now as caretakers: testing the soil for radiation, leading dives for tourists, and keeping the atoll for the time when Bikinians can return. Until then, the surviving original Bikinians and their descendants, which now number in the thousands, are scattered across several other Pacific islands, the United States, and other countries -- victims of what might be called the first nuclear diaspora. Today, as the People’s Republic of China has replaced the Soviet Union as the United States’ greatest rival, concerns are rising over new Chinese nuclear reactors and the possibility of developing weapons from them. US ambassador Robert Wood recently said at a UN conference, “Despite China’s dramatic build-up of its nuclear arsenal, it continues to resist discussing nuclear risk reduction bilaterally with the United States,” signaling the possibility of a reduction of US nuclear arms as well. But despite the rhetoric, the United States has taken no steps to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which came into force in January of this year. As the nation who first brought these doomsday weapons into the world, as the only nation to ever use any of these weapons in war against a foe, and as the possessor of the second-largest and arguably most sophisticated nuclear arsenal on the planet -- the United States is morally obligated to dismantle its nuclear arms, to join the United Nations’ call to ban all such weapons, and to help to forge a path to a new chapter of international peace and cooperation. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources “Castle Bravo.” Atomic Heritage Foundation. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/castle-bravo “Concerns grow over China nuclear reactors shrouded in mystery.” Al Jazeera. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/5/19/concerns-grow-over-china-nuclear-reactors-shrouded-in-mystery Niedenthal, Jack. “A Short History of the People of Bikini Atoll.” Bikini Atoll. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://www.bikiniatoll.com/history.html “Operation Redwing.” Nuclear Weapon Archive. Accessed 18 May 2021. http://nuclearweaponarchive.org/Usa/Tests/Redwing.html “Operation Redwing: 1956.” United States Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Tests: Nuclear Test Personnel Review. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://www.dtra.mil/Portals/61/Documents/NTPR/1956%20-%20DNA%206037F%20-%20Operation%20REDWING%201956.pdf “Revisiting Bikini Atoll.” NASA: Earth Observatory. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/83237/revisiting-bikini-atoll “Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.” United Nations: Office for Disarmament Affairs. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/tpnw For International Conscientious Objectors’ Day, observed annually on May 15, we tell a story about soldiers refusing to serve in the First Gulf War. Thirty years ago this month, at the conclusion of that war, Private First Class Sam Lwin and 24 other Marines were charged with desertion. They were among tens of thousands across the U.S. Armed Forces who applied for conscientious objector (CO) status or otherwise resisted participation in a war that they came to realize was wrong. Lwin, a Burmese-American student and Marine reservist of Fox Company, led 7 others in his unit to resist the military, ultimately joining a mass exodus of the military in which soldiers deserted at higher percentages than even in the Vietnam War. The story of why these soldiers resisted, how, and with whose help is lesser known but deserves greater recognition.

The First Gulf War had a few causes, but the most immediate was a disagreement about oil pricing in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) that came to a head in mid 1990. Iraq, still devastated from the nearly 8-year long Iran-Iraq war that had only concluded a couple years earlier, desperately needed oil price stability to recover. Kuwait also held some significant Iraqi debt which, if they were to disappear, would hasten Iraq’s recovery. When Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah of Kuwait again refused to comply with OPEC production quotas, selling more oil than was agreed upon and thus dragging the price of oil down for the rest of OPEC, President Saddam Hussein of Iraq threatened a military response in early July 1990. The invasion began early the next month. An international coalition largely led by the United States quickly formed to denounce and repel the Iraqi invasion. One major concern was that, after a rapid conquest of Kuwait, Iraq could invade and wrest control of the massive oil fields in U.S.-allied Saudi Arabia. Within days of Hussein’s invasion into Kuwait, the U.S. soldiers were sent into Saudi Arabia. Although the initial objective of Operation Desert Shield, as it was known, was “wholly defensive,” mission creep led U.S. forces to start bombing Iraq within months, starting in mid January 1991. The military coalition that formed against Iraq justified intervention in the regional conflict with a number of reasons. Under Hussein, Iraq had a documented history of human rights abuses, including the use of chemical, biological weapons, and torture. Iraqi human rights abuses continued in Kuwait. But after the Iraqi invasion into Kuwait, the Kuwaiti government exaggerated and even invented alleged Iraqi atrocities, specifically targeting the international and American public with this propaganda through the Hill & Knowlton public relations firm. The PR campaign successfully rallied the public against Iraq. Thus, much of the U.S. public was primed to view Iraqis as monstrous, and themselves as heroic liberators. This rhetoric strongly informed the U.S. military’s vision of itself as well. The resisters within the U.S. military saw things differently. Although Saddam Hussein’s aggression was worth denouncing, many soldiers did not find it heroic to defend a foreign dictator across the world just to keep some oil fields in friendly hands. Many, including Sam Lwin, enlisted with the military as teenagers uncertain about their life paths or how they might pay for college. For many, and especially for POC in the military, patriotism was less of a motivator than the desire for status, funding for education, and a decent paying job in the face of few other options. Others joined genuinely wanting to do good in the world, but over time realized that, in the words of Major General Smedley D. Butler, “war is a racket” meant to benefit a small few. As West Point graduate, former Army career officer, and CO David Wiggins, MD put it, “I had been taught that anything below officer was for inferior types -- minorities, bums, criminals in lieu of jail… Their lives were pretty insignificant, and it was no great loss if a few of them died defending our freedom.” When soldiers applied for conscientious objector status, many faced various threats, docked pay, incarceration and isolation, and psychiatric evaluations. Many POC soldiers experienced racism during Boot Camp, but racist harassment increased significantly for those who came out as COs. As the possibility of a U.S. military intervention around Kuwait increased, Marine Corps Private First-Class Sam Lwin began to seriously consider what it would mean to participate in such a violent venture. He filed for CO status a few weeks before his unit was called to report for duty, and when his application was ignored, he went AWOL. He reached out to the War Resisters League (WRL) which counseled him and hundreds of other COs around the country seeking help in getting out. Throughout the ordeal, Michael Marsh of WRL worked with Lwin and 29 other COs to have their status recognized and to reduce any penalties that may arise -- and Marsh was just one out of dozens of WRL counselors working with COs. Lwin was a student at The New School at the time, and when he told his fellow students about his predicament, the students formed a grassroots group to support and defend Lwin’s conscience. Hands Off Sam!, and later just Hands Off! as the group expanded, was composed of dozens of New School students who helped publicize Lwin’s story, stood with him as he protested before the Marine armory in the Bronx, and packed the court rooms for his and his fellow COs’ court-martials. These groups successfully convinced judges that the Marine Corps’ treatment of COs like Lwin was systemic, abusive, and illegal. Sam Lwin initially faced 7 years in prison; his civilian support had the sentence reduced to just four months. It is often the case that soldiers with doubts about their military participation do not attempt to resist until a fellow soldier does. Sam Lwin was the one who suddenly revealed the possibility of resistance to his 7 other fellow Marines in Fox Company -- without Lwin standing up for his conscience and thus demonstrating that that was even an option, the fates of the 7 other Marines could have been very different. But on the other hand, as Sam Lwin’s story makes clear, soldiers within the military who come to realize their conscientious objections often have a very difficult time having their concerns acknowledged by their superiors. This is especially true in times when the military is actively engaged or preparing to engage in a conflict, a disturbing trend considering the fact that the U.S. armed forces have not seen peace in over 18 years. And with President Biden’s $13 billion dollar military budget increase over Trump’s budget, the American war machine does not seem to be slowing or shrinking. COs within the military often need the assistance of civilian groups to successfully resist. So, for the sake of fellow soldiers who may be inspired by a CO’s resistance, for the sake of a world constantly threatened by the whims of its largest military, and for the sake of the COs themselves, let us do more to promote and honor those who refused to participate in war. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Applebome, Peter. “Epilogue to Gulf War: 25 Marines Face Prison.” The New York Times. 3 May 1991 (accessed 12 May 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/03/us/epilogue-to-gulf-war-25-marines-face-prison.html Cohen, Mitchel. “FOR EACH & EVERY WARRIOR WHOSE STRENGTH IS NOT TO FIGHT.” MitchelCohen.com. 1 June 2013 (accessed 12 May 2021). https://www.mitchelcohen.com/?p=2479 Cohen, Mitchel. “Thousands Said ‘No’ to Gulf War.” Fifth Estate. Summer 1991 (accessed 12 May 2021). https://www.fifthestate.org/archive/337-late-summer-1991/thousands-said-no-to-gulf-war/ Esch, Betsy. “Honoring Our Gulf War Resisters.” Marxists.org. (accessed 12 May 2021). https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/atc/976.html#r9 Gonzalez, David. “MIDEAST TENSIONS; Some in the Military Are Now Resisting Combat.” The New York Times. 26 November 1990 (accessed 12 May 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/1990/11/26/world/mideast-tensions-some-in-the-military-are-now-resisting-combat.html “Marine War Objector Given 4-Month Term.” Los Angeles Times. 24 May 1991 (accessed 12 May 2021). https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-05-24-mn-2367-story.html Wiggins, David. “From West Point to Resister.” Nonviolent Activist, vol. 9, no. 1, 1992, pp. 3–5. Many know about U.S. involvement in and resistance to the Vietnam War, but few are as familiar with the Korean War. Although the war is commonly accepted to have occurred between June 1950 and July 1953, hostilities near the 38th Parallel actually began in May 1949. Moreover, the Korean Armistice Agreement ended armed hostilities in the Korean peninsula but never actually ended the war -- a technicality that until very recently mandated military service for all South Korean men.

After Japanese Imperial forces left the Korean peninsula at the end of the Second World War, political divisions between Koreans came to a head. By 1948, violent government repression of communists and dissidents led to an atmosphere of distrust and betrayal. When a U.S.-backed Korean general election was announced for July 1948, several significant groups including the Korean communists and many noncommunist Korean politicians refused to participate. A separate government was formed in the northern part of the country, and after months of armed conflict at the emerging border, the northern Korean People’s Army (KPA) made a drive into the south in June 1950. The United States, under the authority of the United Nations Security Council, responded immediately, landing troops within a month of the incursion and kicking the U.S. Selective Service system back into gear. Among the roughly 1.5 million people whose draft numbers were called were James Lawson and Gene Sharp. But unlike most, these two men refused to participate in any capacity. Born to a Methodist minister, Lawson’s refusal stemmed from the deep contradiction he found between the teachings of Jesus and participation in war. When he received his draft card within the first few months of the Korean War, instead of reporting for duty, 22-year old sociology student James Lawson simply returned the card to the Selective Service Board and was promptly arrested. During his incarceration for draft resistance, Lawson wrote “I’m an extreme radical which means the potent possibility of future jails...” -- foreshadowing his future work in the civil rights movement. After being released from prison in 1953, Lawson went to India as a Methodist missionary and studied Gandhian satyagraha (“truth force” nonviolent resistance). Shortly after returning to the United States, while getting his Master’s at Oberlin, Lawson met a young Martin Luther King, Jr. Recognizing that Lawson had unique expertise to share, King urged him to go South to join the nascent desegregation movement as soon as possible. He settled on Nashville, a segregated Southern city, but one with all the elements that could give rise to change. Within a year, the students he trained started the Nashville Lunchcounter Sit-in Campaign, one of the main sparks which ignited the civil rights movement. Gene Sharp was similarly born to a Protestant minister, was called for military service during the Korean War, refused to cooperate with the Selective Service Board, and was imprisoned for nine months for his noncompliance. While Sharp was already learning about nonviolent strategy before his incarceration, after his prison term, Sharp continued to develop a pragmatic approach to nonviolent resistance related to but distinct from the more spiritual Gandhian conception. For Sharp, nonviolent action was a means of exerting combative power that could be every bit as aggressive and forceful as war, except without violence. Over the decades, Sharp documented and developed the theory of nonviolent action even further, writing handbooks used by successful nonviolent revolutions around the world to face down and dismantle violent authoritarian regimes: protests from Tiananmen Square to Tehran, revolutions against dictators in Eastern Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s, the Arab Spring and especially the Egyptian Revolution that ousted Hosni Mubarak, and beyond. His theories of “civilian-based defense” as well as the “198 Methods of Nonviolent Action” he assembled have been borne out successfully in the real world for decades, and outside of the United States, his ideas have been considered especially dangerous to authoritarian regimes. It is no coincidence that both of these influential men were also students and colleagues of the great leftist pacifist leader A.J. Muste, co-founder of the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) and namesake of the Conference Center at the Voluntown Peace Trust. Lawson joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the affiliated Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) shortly after his incarceration. Through FOR and CORE, Lawson met Muste, who in turn introduced Lawson to the great organizers Bayard Rustin and James Farmer. In fact, it was AJ Muste and Glenn Smiley who created the FOR Field Secretary position for Lawson to teach nonviolent action in Nashville. Sharp worked as a secretary for Muste after his own prison term, and was active with the early CNVA as an activist until he turned to academia, becoming a researcher of nonviolent movements. After some decades out of social movements, Gene Sharp ultimately returned to the Voluntown Peace Trust for the CNVA 50th anniversary in 2010. The draft resistance of James Lawson and Gene Sharp led both men to cross paths with other influential leaders of justice, and to do foundational and revolutionary work that continues to reverberate in the United States and around the world. In South Korea, where military service for all men ages 18-28 has been mandated since the Korean Armistice Agreement, conscientious objection to military service was not recognized until very recently. Refusal meant multiple prosecutions, repeated fines, and/or imprisonment. But in June 2018, the South Korean Constitutional Court ordered the government to recognize conscientious objection as a valid reason to refuse conscription, and in January 2021, the first South Korean conscientious objectors on non-religious grounds were accepted for alternative service. These victories were made as a result of 20 years of organizing by World Without War, a South Korean affiliate of War Resisters’ International. With the possibility for Korean reunification now closer than at any time since the Korean War, it is clear that a conversion from military readiness to community-building, social healing, and coalition-based nonviolent resistance to further injustice will be necessary to successfully integrate the divided states. With conscientious objection now legally recognized in South Korea, and the history of war resisters in the United States making such immense contributions to domestic and international justice, might this development in South Korea form new leaders of a nonviolent action movement? -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Dickerson, Dennis C. "James M. Lawson, Jr.: methodism, nonviolence and the civil rights movement." Methodist History, vol. 52, no. 3, 2014, p. 168+. Accessed 6 May 2021. https://go.gale.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA378369331&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=00261238&p=AONE&sw=w “James Lawson.” SNCC Digital Gateway. Accessed 4 May 2021. https://snccdigital.org/people/james-lawson/ Roberts, Sam. “Gene Sharp, Global Guru of Nonviolent Resistance, Dies at 90.” The New York Times. 2 February 2018 (accessed 4 May 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/02/obituaries/gene-sharp-global-guru-of-nonviolent-resistance-dies-at-90.html Smithey, Lee. “Gene Sharp has died and the world has lost a global educator.” Peace and Conflict Studies at Swarthmore College. 31 January 2018 (accessed 4 May 2021). https://blogs.swarthmore.edu/academics/pcs/2018/01/31/gene-sharp-has-died-and-the-world-has-lost-a-global-educator/ “South Korea: Conscientious objection on non-religious grounds recognised by Supreme Court and MMA first time.” War Resisters’ International. 15 March 2021 (accessed 4 May 2021). https://wri-irg.org/en/story/2021/south-korea-conscientious-objection-non-religious-grounds-recognised-supreme-court-and “THIS WEEK’S PROFILE: REV. JAMES LAWSON.” Memphis Public Libraries. Accessed 4 May 2021). https://www.memphislibrary.org/diversity/sanitation-strike-exhibit/sanitation-strike-exhibit-march-17-to-23-edition/this-weeks-profile-rev-james-lawson/ |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed