|

The turn of a new year can often feel significant, but this one feels especially so. The vaccines for covid-19 are starting to be distributed now, and with the incoming Biden administration taking over from the catastrophically incompetent President Trump, many have good reason to feel optimistic about 2021. But covid-19 did not simply reveal the vulnerability of this country’s healthcare and pandemic response system; it also exposed the economic fragility of so many working Americans’ living situations. Despite moratoriums and ban orders, people are continuing to lose homes at unprecedented rates. And even for those who do not suffer eviction, most are still forced to pay rent even as their working hours have been reduced. Many are falling further into debt just to survive. As important as the vaccine will be in the months ahead, it will not solve the debt and homelessness crises that this year have exacerbated. But looking forward to the turn of this new year, and ahead to the inauguration of a new President, perhaps we can take some lessons from the ancient past to give us inspiration on how to recover from the immense trauma our society has recently experienced.

In the ancient Sumerian and Babylonian kingdoms, debt seems to have been invented before writing. According to anthropologist David Graeber, the concept of debt and its twin, interest-bearing loans, was likely invented by government administrators to incentivize local traders and still receive a cut. But the concept quickly jumped from commercial debts to consumer or individual debts. By around 2400 BCE, it was apparently already common practice for peasant families suffering bad harvests to take advance loans from wealthy merchants or officials, having their goods, lands, and even family members taken as collateral. People taken in this way were debt-peons: a kind of enslavement in which one is forced to work for the “lender” (merchant/official) until the “borrower” (peasant) can redeem the person in peonage with the debt owed -- but of course, this became more difficult to do as more the borrower’s assets would be seized and family broken apart. To make matters worse, this was not simply an individual or family-level problem, but one that threatened to rip society apart completely. Bad harvests usually result from a regional issue like drought or flooding. Consequently, every bad harvest meant that large portions of the peasant population would be thrown into complete crisis. From Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years: “Before long, lands lay abandoned as indebted farmers fled their homes for fear of repossession and joined semi-nomadic bands on the desert fringes of urban civilization” (Graeber 65). Therefore, to avoid the periodic threat of absolute societal collapse, it became customary for new leaders to enact “clean slate” general amnesty to all outstanding consumer debts upon their ascensions, as well as periodically throughout their reigns. Indeed, redemption from debt-peonage appears to be the first recorded use of the word “freedom” at all. The concept of “clean slate” debt amnesty was not unique to the Sumerian and Babylonian civilizations. In the Book of Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible, a similar debt-bondage crisis gripped Judaea. Families were broken apart, with some children going to serve in the households of wealthy neighbors, while others being sold into slavery abroad. In 444 BCE, a Babylonian-raised Jewish governor instated policies of debt forgiveness in Judaea, the most famous of which was the Law of Jubilee: “in the Sabbath year” (i.e. after seven years) all debts would be cancelled and all those in debt-peonage would be released. This theme of liberation from bondage echoes through much of ancient Jewish history, and was taken even further in Christian theology with the redemption of Christ: “forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.” In ancient Greek history, Solon “the Lawgiver” is viewed as an especially important early reformer who laid the foundation for Athenian democracy. By his time, the debt-peonage crisis had spread to Greece, and Athenian society was terribly divided by the few wealthy creditors and the masses of farmers forced to sell themselves and their family members to them. Seeing this primarily as a moral problem of society originating in unrestrained greed, Solon included in his famous reforms the policy of seisachtheia, the “shaking off of burdens.” All debt-peons were returned home, all current debt contracts were cancelled, and future debt slavery was forbidden. In the popular imagination, if not in fact, Solon’s reforms ushered in a golden age of Athenian civility, sophistication, and heroism which ultimately came to fend off the much more powerful Persian Empire. Perhaps to many of us today, the concept of debt forgiveness sounds absurd, even unethical. Don’t those people owe that money though? If they couldn’t pay it back, then maybe they shouldn’t have gotten the loan in the first place. Don’t their creditors have a right to get back what they had agreed upon? And yet, that line of thought only obscures the unjust reasons for having acquired that debt in the first place. Yet, for hundreds of years and across diverse peoples, the practice of periodically canceling all outstanding debt was commonplace, popular, and to a large degree, the practical and necessary policy to avoid massive social crises. In more modern times, the very first community land trust in the United States, started by Black civil rights activists as a safe haven for Black farmers, was foreclosed upon after years of being denied the same government debt forgiveness their White neighbors received. Americans are saddled with enormous debts, mostly from credit cards, auto loans, and student loans. Due to the overwhelming personal debt that so many Americans face today, it is not uncommon now for a college-graduate to return home to their parents for a few years. Many of those with the best training and education are financially unable to create, innovate, and enact the plans they have made. Countless couples have put off having children indefinitely for fear of an uncertain future. And now, despite ostensible legal protections preventing this very thing from happening, record numbers of people have lost their homes this year through no fault of their own. This is our modern consumer debt crisis. No vaccine will cure this cycle of debt; no vaccine will prevent evictions. Recovery from covid-19 will take so much more than mass immunization. This was a landmark year. A dramatic change in leadership is just a few weeks away. The time feels right to wipe the slate clean. It’s time to bring back the debt jubilee. -- David Graeber was a cultural anthropologist, one of the primary theorists of the Occupy Wall Street Movement, and the thinker behind many recent analyses of modern life, such as the significance of political direct action, the meaning of “bullshit jobs,” and, of course, debt. Something of a radical academic, his writing style is at once familiar and approachable while also conceptually challenging. David Graeber suddenly passed away this year at the age of 59. If you would like to learn more about debt-cancellation and the modern consumer debt crisis, check out Rolling Jubilee, a project of Strike Debt which formed out of the Occupy Wall Street movement (http://rollingjubilee.org/). The South-Eastern Connecticut Community Land Trust (SECT CLT) is a nonprofit dedicated to establishing permanent affordable housing using a unique and equitable system first pioneered in the United States by civil rights activists. With a recent change in staff, SECT CLT is getting ready to renew a push to continue its mission in 2021 (https://sectclt.org/). If you are interested in assisting local community members who have recently lost their homes in the Norwich area, a new group has formed for that purpose. The first project is to create a directory of services and essential information, especially for those who are newly unhoused and thus might not know the systems in place to help them. Visit the Norwich Homeless Resource Volunteers group page to learn more (https://www.facebook.com/groups/658687648159825) Sources & Further Reading: Amadeo, Kimberley. “Current US Consumer Debt.” The Balance, updated 28 December 2020. https://www.thebalance.com/consumer-debt-statistics-causes-and-impact-3305704 Graeber, David. Debt: The First 5000 Years. Melville House, 2011. Hudson, Michael. “A debt jubilee is the only way to avoid a depression.” The Washington Post, 21 March 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/21/debt-jubilee-is-only-way-avoid-depression/ The child’s parents lived in an old, proud country that had come under the “influence” of a much more powerful country across the sea. Conflicts had led to civil war, and the country was only just starting to recover. To appease his imperial bosses, the king of the country coordinated a census, requiring all citizens to go register in their families’ ancestral town. The child’s parents would have to join the many other people on the roads and travel to Joseph’s hometown to register.

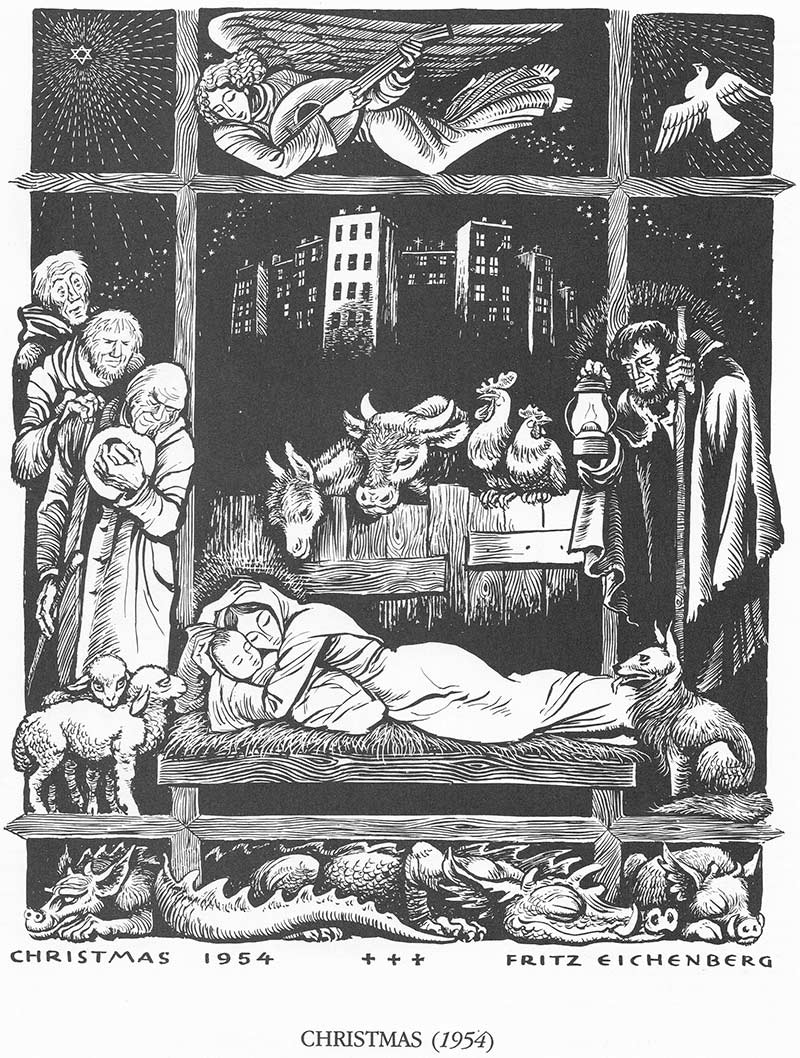

But there was a problem: the teenaged Mary was very pregnant. She could only move so fast. And so when she and Joseph finally arrived at an inn to stay the night, they found that they were too late: all the rooms were already full. But they could stay in the barn; at least it would be a roof over their heads. That night, among the hay straw and animals, Mary went into labor. One can only imagine how scared the two young parents must have been, trying to deliver their first baby with no one to help them. Some local shepherds, considered rather low-class in that country, were collecting their sheep in a field nearby and must have heard the commotion of Mary giving birth -- they discovered a young couple with their newborn son in the stable: the parents weak and tired, but filled with joy at the health of this perfect child. Many are familiar with the Christmas nativity story, but the story is worth reconsidering specifically through the lens of 2020. Despite the eviction ban under the Covid-19 pandemic CARES Act (which ended in July) and the subsequent executive order to halt even more evictions in late August through to the end of the year, people in the United States have been losing their homes at record rates. And yet, even with the shutdowns, lost wages, the bare minimum of federal aid, and all the other attending difficulties of the pandemic, many Americans still believe that it must somehow be due to a personal failing that someone loses their job, or has to sleep outside, or gets pregnant at 14. It is practically the default narrative of hardship in our country. The nativity story, however, is specifically about a young, itinerant, pregnant couple dealing with difficult challenges due to circumstances outside of their control. No one has ever accused Joseph of being an alcoholic and waking up too late, or blamed Mary for being lazy and not walking fast enough -- Christians have long understood that the occupied inn and the lowly circumstances of the birth were the cards dealt to the couple, and a message to us. Many more people today are being dealt worse hands for reasons outside of their control. This was true before the pandemic arrived, but Covid-19 has exacerbated the problems. But Covid-19 has also broken open new possibilities, new visions for the future. Like Mary and Joseph of the nativity story, we live through a transitional period in which the old world is dying and the new struggles to be born. Moments like this are full of real, suffering people. So let us regard each other with the same generosity of spirit as Christians have always regarded Mary and Joseph. We leave you with this poem from Thomas Merton, Trappist monk and committed promoter of social justice. “Room in the Inn” Into this world, this demented inn in which there is absolutely no room for him at all, Christ comes uninvited. But because he cannot be at home in it, because he is out of place in it, and yet he must be in it, His place is with the others for whom there is no room. His place is with those who do not belong, who are rejected by power, because they are regarded as weak, those who are discredited, who are denied status of persons, who are tortured, bombed and exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world. - Thomas Merton Sources: Eichenberg, Fritz. “Christmas 1954” (or, “A Christmas Meditation for a Troubled World”). Goldstein, Matthew. “Landlords Jump the Gun as Eviction Moratorium Wanes.” New York Times, 23 July 2020 (updated 2 September 2020). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/23/business/evictions-moratorium-cares-act.html Jones, Zoe Christen. “COVID driving record homelessness figures in NYC, advocates say.” CBS News, 11 December 2020. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/covid-driving-record-homelessness-figures-in-nyc-advocates-say/ar-BB1bR7TU Merton, Thomas. "No Room in the Inn.” In 1914, New York City experienced its worst winter in years. Massive snowstorms repeatedly drove upon the city while temperatures would dip below 0 degrees Fahrenheit. In just two nights, 16 individuals died of sheer cold, and scores more had to be hospitalized from frostbite. Those who could find shelter at all lit fires indoors in desperate attempts to survive the frigid nights, risking the safety of other buildings nearby. Those who could not find shelter often suffered injuries or illnesses, ending up at the hospital and occupying a bed for longer than a typical patient. Some others would purposely choose arrest; at least jail guaranteed some food and a warm place to sleep.

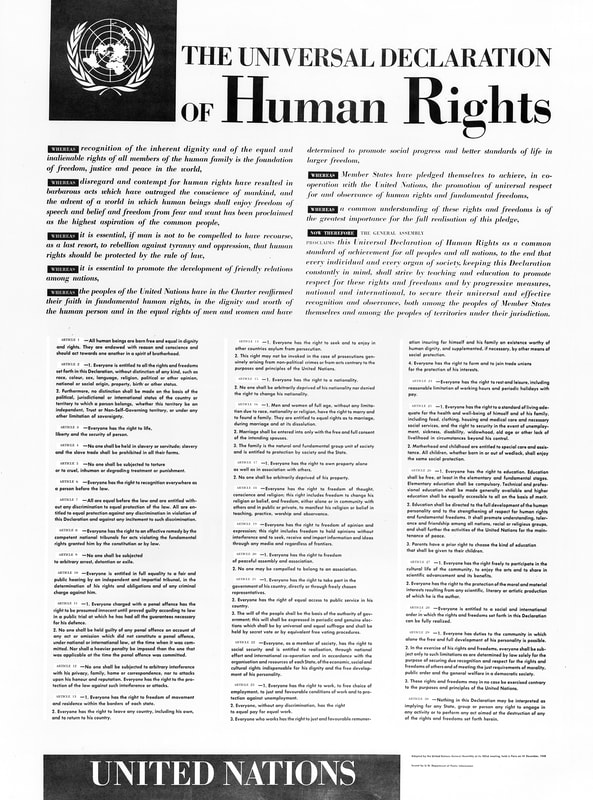

Nationally, unemployment had been on the rise, reaching a staggering ⅓ of available workers out of a job. In New York City, hundreds of unhoused people, mostly recently-unemployed men, lined the buildings to soup kitchens and shelters. Formerly the sole domain of religious groups, new charitable organizations sprang up to support and oftentimes shepherd the economically vulnerable into this or that cause. Favorable interpretations for these new organizations viewed them as modern, scientific, and wholly apolitical -- seen as an advancement over the improvised system of neighborhood power brokers developed by Tammany Hall. But critics pointed out the immense sums these groups brought in, the comparatively meager and low-quality food and accommodations provided for those in need, and the quick manner in which the biggest charitable groups banded together to create a monopoly on the whole enterprise. One couplet became popular among some in that time: “The organized charity, scrimped and iced / In the name of a cautious, statistical Christ.” On February 13, in the middle of the worst blizzard the city had seen in years, a wealthy socialite went out dancing, leaving her chauffeur to wait in the car. The unfortunate chauffeur was found in the car frozen to death later that evening. Over the next couple weeks, the city government would work on establishing its first “municipal employment bureau”: a system to match unemployed workers and their skills to open jobs. When the city found that it suddenly needed many temporary workers to clear the streets of snow and ice, the list at the new bureau was invaluable in finding the necessary labor. However, the workers quickly realized how even this new system was rigged, and some became completely disillusioned with the new system. From Thai Jones’ More Powerful than Dynamite: ‘Thirty-five cents an hour was no fortune, considering the severity of the work. And that old foe, graft, incised deeply into even this meager sum. Each person sent from the employment bureau was directed to a private contractor who took twenty-five cents off the top plus a dime to hire the shovel. After an eight-hour day, and another nickel for the foreman, a man might have a dollar left. But he didn’t get a dollar, he got a ticket, which he could use only at a particular saloon. There he was charged 20 percent to cash the thing and was forced to buy a drink…’ (Jones 70) It was in this difficult situation that a young 19-year old man by the name of Frank Tannenbaum started leading an “army” of unemployed and unhoused men into the churches of Manhattan. Frank was a passionate member of the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W. aka “Wobblies”) and fully believed in the union’s message of establishing true justice and human brotherhood through solidarity and direct action. Night after night through the snow and cold, the “Boy I.W.W. leader” Frank Tannenbaum lined up the other homeless men who wished to join him into marching ranks and led them through the city, politely but firmly demanding from the priests of these churches to live up to their Christianly values and provide food and shelter for just the evening. Some nights there were several dozens of men with Frank; other nights, well over a hundred. Word spread quickly: the wealthiest churches requested extra security from the police, while the press ran typical slanderous stereotypes of rabble-rousers. And yet, neither violence nor property destruction was ever reported to the police by these churches. From Thai Jones again: “The out-of-work army had shown the highest qualities of anarchism. It was spontaneous, nonviolent, dignified, and viciously subtle in its revelation of hypocrisy” (Jones 94). After just over a week of demonstrating the power of direct action, Frank and his “army” were led into a trap by police, and Frank was promptly arrested, had bail set to to an incredible $5000, and was soon after sentenced to the maximum sentence: a year of hard prison labor. Frank would eventually leave prison and become a respected professor, but his actions in early 1914 seemed to inspire seasoned revolutionaries like Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman as well as lesser-known anarchists and direct-actionists to continue this new revolutionary chapter. We live in a different world, but some similarities are striking. After over a decade of steadily decreasing numbers of homeless people in the United States, that number has started to increase again in the last two years. Unemployment rates skyrocketed earlier this year due to covid-19 and have only recently begun to drop primarily because, without government assistance, people are being forced back to work. We have a new incoming government, but few harbor genuine hope in its competency or political will, despite Biden and Harris’ progressive posturing. And then there’s the snow. Because more people are losing their homes, the government systems in place to support those people, which were already underfunded and stretched too thin, are in crisis. Our local shelters are full. Camps are a temporary solution, but are unsafe and unsanitary, especially for women, queer people, and people with disabilities. And, of course, being unhoused makes every other part of one’s life more difficult. Addressing homelessness, however, is complex and multifaceted. Does that mean trying to prevent homelessness, or does it mean supporting people who are already homeless? Does preventing homelessness mean physically defending tenants from evictions? Does supporting already unhoused people mean helping them where they are, or does it mean finding them a new home? How can we balance immediate needs with long-term solutions? Frank Tannenbaum’s solution in 1914 was not a permanent one either, but it was a way for the men to win some dignity, survive the night, develop solidarity with each other, and inspire others. That is the beauty of direct action. Sources: Jones, Thai. More Powerful Than Dynamite: Radicals, Plutocrats, Progressives, and New York’s Year of Anarchy. Bloomsbury, New York: 2012. Moon, Robin J. “Where do homeless patients go after being treated for COVID-19?” PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/where-do-homeless-patients-go-after-being-treated-for-covid-19 Today is the 72 anniversary of the publication of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the foundational document for international human rights law. Its purpose was primarily to serve the UN mission: to maintain freedom, justice, and peace in the world so that individuals can best develop themselves. That mission can only be achieved by a universal recognition of all humans’ inherent dignity and equal rights, which the UN detailed in the 1948 document. Despite some flaws and ambiguities, it is a remarkable political document -- one that feels both familiar to the American reader due to similarities with the Declaration of Independence and the US Bill of Rights -- yet it also feels new, bold, and exciting.

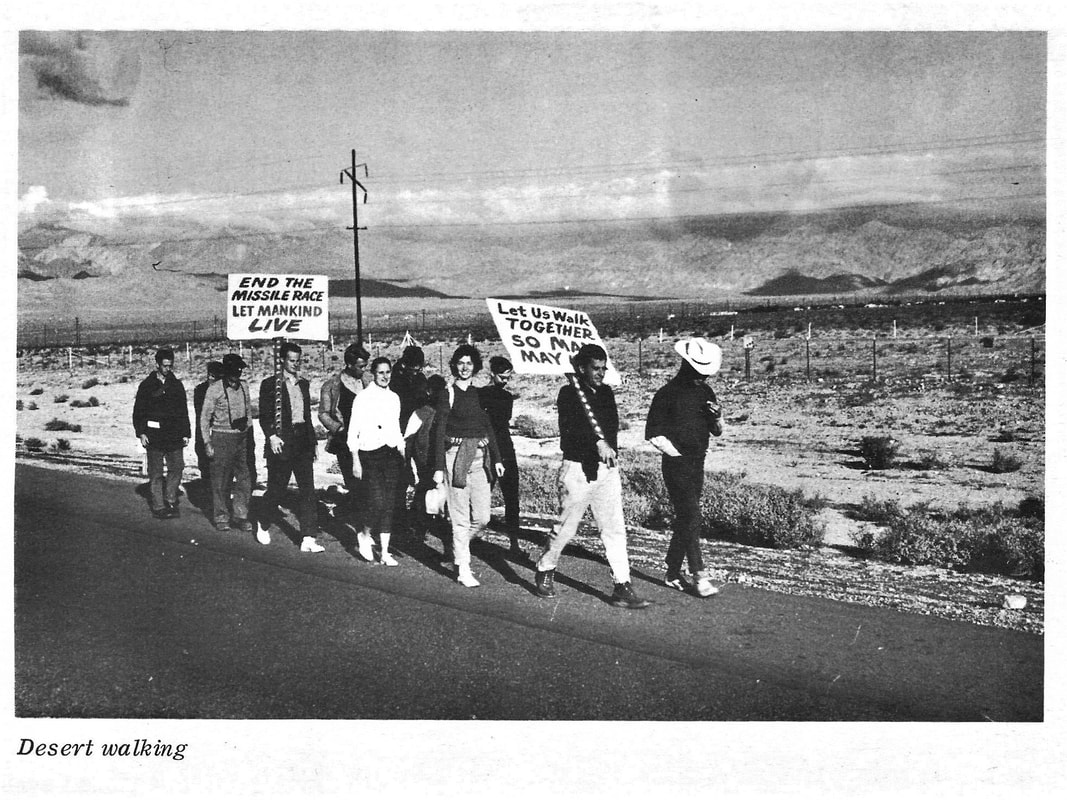

It is no use to anyone if this Declaration was made and never read. The Declaration explicitly states that the system of values it lays out can only function if there is common understanding about the meaning and purpose of those values. To that end, here is the powerful, Universal Declaration of Human Rights in its entirety. -- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) Preamble. Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge, Now, Therefore THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY proclaims THIS UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction. Article 1. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2. Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4. No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5. No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6. Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7. All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8. Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law. Article 9. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile. Article 10. Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him. Article 11. (1) Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence. (2) No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed. Article 12. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks. Article 13. (1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. (2) Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. Article 14. (1) Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution. (2) This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations. Article 15. (1) Everyone has the right to a nationality. (2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality. Article 16. (1) Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution. (2) Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses. (3) The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State. Article 17. (1) Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others. (2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property. Article 18. Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance. Article 19. Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. Article 20. (1) Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association. (2) No one may be compelled to belong to an association. Article 21. (1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. (2) Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in his country. (3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures. Article 22. Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality. Article 23. (1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment. (2) Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work. (3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection. (4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests. Article 24. Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay. Article 25. (1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control. (2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection. Article 26. (1) Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit. (2) Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace. (3) Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children. Article 27. (1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. (2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author. Article 28. Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized. Article 29. (1) Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible. (2) In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society. (3) These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations. Article 30. Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein. Source: “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html This passed Tuesday marked the 60th anniversary of the start of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. On December 1, 1960, sixteen committed individuals took off from San Francisco’s Union Square on foot, determined to walk across the United States and Europe to Moscow in order to spread their message of nuclear disarmament to Americans, Europeans, and Russians alike. Bradford Lyttle, one of the main organizers of the Walk, wrote an account of the experience, including the unique opportunities and encounters that walking across 6000 miles revealed.

Almost everywhere they went, people of all kinds were drawn to the artists, anarchists, academics, and idealists who took part in the Walk. What is striking about so many of these interactions is how they revealed the sometimes surprising private feelings of ordinary citizens about war, peace, conscience, nuclear weapons, and the future of humanity in an era of extreme conformity. In our current culturally divided moment, perhaps it is a good reminder that not everyone who disagrees with us is the enemy, that one’s actions do not always reflect one’s beliefs, and that a single interaction can inspire great acts of kindness from ordinary people. The following are excerpted accounts of the first few weeks of the Walk from Bradford Lyttle’s book You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. -- Our alarm went off at 5:30 next morning. Everyone was so sore and tired that we decided to sleep until 7:30. Then we took two hours to repack our luggage. All of us had too much gear. We were afoot by 11:00. At Millbrae, police forbade leafleting for one mile. We complied, feeling it would shock the Executive Committee [of the Committee for Nonviolent Action “CNVA”] in New York, if we were jailed the second day out. Joe Glynn led us a mile off the route to picket a Liquid Carbonics plant and other industries with military contracts. In the evening, several marchers met with members of the Palo Alto Peace Center. We reached Redwood City and separated to spend the night in homes of supporters. December 3, we began walking earlier, and passed through Stanford University. Students readily accepted leaflets. In Redwood City’s municipal park, we held an open air meeting at noon with more than 100 sympathizers. A Rabbi and a minister brought their Sunday School classes to meet us. Sympathizers gave us cookies and money. From 4:30 to 5:30 we picketed Moffat Air Force Base. UPI sent a reporter. A man stopped his car. He said he recently had left his job building Polaris [intercontinental nuclear] missiles at a nearby Lockheed factory. He couldn’t square manufacturing missiles with his conscience. He pressed $5 into my hand. Members of the San Jose Quaker Meeting prepared our supper and we talked with them afterwards. Then we held an internal meeting. Since we were already eight miles behind our schedule, we decided we should walk from 6:00 AM until noon every day, with no time out for picketing or meetings. A moment of truth had also arrived in regard to personal belongings. Each marcher was asked to reduce his gear to a minimum and be responsible for his things. -- We reached the Monterey Peninsula on December 6. Milton and Jane Meyer served us supper at their Carmel home. Later, Berkeley station KPFA interviewed us. [The Hilary Harris filmmakers] Saul Gottlieb and Ray Wisniewski arrived in the middle of the interview. A breakdown of their Volkswagen had delayed the mobile movie-takers for three days. The Mayers knew that radical peacewalks seldom come to Carmel. They had decided to work us hard. At 7:00 the next morning we and half a dozen local sympathizers picketed Fort Ord. Reporters were on hand. At 7:30, we walked through the town of Seaside, leafleting. At 8:00, a car whisked us to picket the Naval Air Facility Base near Monterey. The Monterey Police Chief was on hand and very amiable. “Everyone has a right to express themselves. If you believe this is the way to do it you are welcome to do so in Monterey.” So ran the gist of his statement. We proceeded through the campus of Monterey Peninsula College. Throngs of students gathered to read our leaflets and discuss our views. We were permitted to leave only after we had promised to send marchers back in the afternoon to speak in classes and debate in the student lounge. We walked through downtown Monterey. A drugstore owner gave us a canvas waterbag. After picketing for 25 minutes at the Presidio, an Army language school, we walked and leafleted in Pacific Grove. A parade through Carmel and meetings in classes at Carmel High ended our whirlwind tour of Monterey Peninsula. In the afternoon, half a dozen marchers returned to Monterey Peninsula College and went also to Emerson College. Everywhere, students were eager to discuss our ideas, although few seemed to agree with them. -- We marched into Santa Maria, a town near the missile testing range at Vandenberg AFB, on the 14th. Santa Maria is “The Missile Capital of the Free World” according to the masthead of its newspaper. A courageous Methodist minister opened his church to us. Likely more than half his congregation was directly or indirectly involved in testing military rockets. In the afternoon, we reached the main entrance of Vandenberg. An Air Force officer threatened me with violence if I took his picture. On the way there, I was hitchhiking, and two men who earlier had lingered at the fringe of a public meeting in Santa Maria, gave me a lift. They were hostile. I feared they might be planning to “give me a ride”. But they only wanted to talk. One was a jet fighter pilot on the aircraft carrier Ticonderoga. He was a troubled young man. “In training class an officer said, ‘You men are killers now. Don’t forget that!’” The boy shook his head and grinned uneasily. “I’m a killer. I’m supposed to be a killer,” he said. His companion serviced missiles at Vandenberg. He was more detached from his work than the pilot, and argued the strategy of deterrence with me. I was unable to shake his conviction that the missiles would never be used. On the 15th, we resumed the March at Vandenberg’s main gate. CNVA Committee member Sam Tyson and Joe Glynn had been picketing. Police gave them tickets for parking by the side of the road -- on Government property. About two miles out from the gate, out in the lonely, hilly dunes, a man stopped his car and took movies of us. I talked with him. He was a physicist who worked with Convair on Atlas missiles. His heart was heavy, his conscience raw. A Catholic and a Thomist, he justified his work on the grounds that the missiles were being used for peaceful space exploration, as well as to carry H-bombs. But the rationalization obviously was thin. “I’m due for a promotion soon,” he said gloomily. How many employees felt as he did in the great, sprawling Base, whose gantry cranes squatted like some strange animals on the beach, blinking their red and green warning lights? At least one more. A pretty young lady stopped her car where we were resting and gave us $5. She taught grade school on the Base. A powerful impulse drove her to join us, but she had a family to support. She drove beside us about two miles, discussing our program. -- On the 19th, the March picketed recruiting offices in Oxnard. On the 20th, we attended a public meeting in the Santa Monica Unitarian Church. Every night we succeeded in finding accommodations in churches or private homes. Much of the walking was inspiring and exhilarating. In the winter, the countryside is beautiful in Central and Southern California. -- Roberta Ridley, a Los Angeles mother who had been deeply moved at the Santa Monica meeting, provided hospitality for three nights. I warned her about the dangers of having 16 individualistic peacewalkers in her home. She was undaunted. When she was able, she took responsibility for our meals, too, and I don’t think we met many people in 5000 miles whose devotion and generosity exceeded hers. Source: Lyttle, Bradford. You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. Greenleaf Books, Raymond, New Hampshire: 1966. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed