We at the Voluntown Peace Trust have been working to preserve and communicate the history of our property, the groups who have used it, and the diverse activities that have sprung from our resources. We also conduct research on the 20th century U.S. peace movement, from which VPT was born. Below, you will find summaries of the various eras in our organization's history. We will continue to update this page as we do more research.

We also post a new story from the history of the peace movement each Thursday on Facebook and on our blog "A Peace of History." To see those posts, please click here.

We also post a new story from the history of the peace movement each Thursday on Facebook and on our blog "A Peace of History." To see those posts, please click here.

Before Voluntown: A Legacy of Violence

In 1721, white settlers of mostly English and Scotch-Irish descent incorporated a small village in the area between Jewett City to the west and the powerful Narragansett nation to the east. Dozens of Pequot settlements had dotted the area just a few decades previously, but by 1721, the Pequot War and colonial law had wiped them out. The white colonists settled their village upon the ruins of one of these Pequot settlements, so recently evacuated by its Native builders and stewards, and named the new settlement “Voluntown,” after the volunteer colonial soldiers who fought in King Philip’s War.

The story of the Pequot genocide does not begin here. In fact, by the time of Voluntown’s incorporation, the Pequot nation had already been declared extinct by the colonial government for 83 years. Some may be familiar with the story of the Pequot War, the first major violent conflict between Native Americans and English colonists in New England, which ended in the genocide of the Pequot people. The unprecedented destruction and brutality of the English colonists, however, shocked their Mohegan and Narragansett allies. The Mohegans largely remained faithful allies to the English colonists, but the Narragansetts and many other Native peoples of the area became ever more wary.

Meanwhile, to the north, the Wampanoag nation had been dealing with English settlers of their own. In 1620, the Wampanoag leader Ousamequin (a.k.a. Sassasoit) had sent Tisquantum (a.k.a. Squanto) and Epenow to teach the helpless Mayflower Pilgrims to plant corn and survive the winter. By the time Ousamequin’s son, Pumetacom, had become the new Wampanoag leader, however, the situation had changed dramatically. Pumetacom (a.k.a. Metacomet), called the Christian name “Philip” for his father’s famous good relations with the Mayflower Pilgrims, recognized the threat posed by the English colonists to Native life. War broke out over a small controversial issue, as they often do, involving the murder of a Christianized Wampanoag man and the execution of his alleged Wampanoag murderers by the colonial government. The Narragansett, former allies of the English but who had by 1675 declared official neutrality, were accused by the English of harboring Wampanoag soldiers, and suffered preemptive attacks by their former allies as a result.

When the English brought war to the Narragansett nation, they brought their brutality to the Pequot survivors living in eastern Connecticut under Narragansett protection as well. Doubling the tragedy was that among the Mohegans, still allies of the English, were the surviving “western” Pequot people who had been absorbed into the Mohegans decades earlier. For three years, King Philip’s War consumed most of New England, destroying 17 English towns, damaging 52 other English towns, destroying untold numbers of Native settlements, and claiming the lives of thousands, including as much as 40% of all Native people of the area. There is some evidence to suggest that around the main house at the Voluntown Peace Trust may have been the site of a small Pequot village, and local stories point to other parts of the VPT property, especially the area around Ahimsa Lodge, as one of the temporary sanctuaries used by Pequot women and children fleeing for their lives after the English had slaughtered the men of the community.

We at the Voluntown Peace Trust recognize and honor the fact that we simply serve as stewards of this land we hold in trust. We are building relationships with local Tribes who have a history tied to this land to learn more about that history and engage in discussions about the most responsible, respectful and cooperative way to steward the land.

The story of the Pequot genocide does not begin here. In fact, by the time of Voluntown’s incorporation, the Pequot nation had already been declared extinct by the colonial government for 83 years. Some may be familiar with the story of the Pequot War, the first major violent conflict between Native Americans and English colonists in New England, which ended in the genocide of the Pequot people. The unprecedented destruction and brutality of the English colonists, however, shocked their Mohegan and Narragansett allies. The Mohegans largely remained faithful allies to the English colonists, but the Narragansetts and many other Native peoples of the area became ever more wary.

Meanwhile, to the north, the Wampanoag nation had been dealing with English settlers of their own. In 1620, the Wampanoag leader Ousamequin (a.k.a. Sassasoit) had sent Tisquantum (a.k.a. Squanto) and Epenow to teach the helpless Mayflower Pilgrims to plant corn and survive the winter. By the time Ousamequin’s son, Pumetacom, had become the new Wampanoag leader, however, the situation had changed dramatically. Pumetacom (a.k.a. Metacomet), called the Christian name “Philip” for his father’s famous good relations with the Mayflower Pilgrims, recognized the threat posed by the English colonists to Native life. War broke out over a small controversial issue, as they often do, involving the murder of a Christianized Wampanoag man and the execution of his alleged Wampanoag murderers by the colonial government. The Narragansett, former allies of the English but who had by 1675 declared official neutrality, were accused by the English of harboring Wampanoag soldiers, and suffered preemptive attacks by their former allies as a result.

When the English brought war to the Narragansett nation, they brought their brutality to the Pequot survivors living in eastern Connecticut under Narragansett protection as well. Doubling the tragedy was that among the Mohegans, still allies of the English, were the surviving “western” Pequot people who had been absorbed into the Mohegans decades earlier. For three years, King Philip’s War consumed most of New England, destroying 17 English towns, damaging 52 other English towns, destroying untold numbers of Native settlements, and claiming the lives of thousands, including as much as 40% of all Native people of the area. There is some evidence to suggest that around the main house at the Voluntown Peace Trust may have been the site of a small Pequot village, and local stories point to other parts of the VPT property, especially the area around Ahimsa Lodge, as one of the temporary sanctuaries used by Pequot women and children fleeing for their lives after the English had slaughtered the men of the community.

We at the Voluntown Peace Trust recognize and honor the fact that we simply serve as stewards of this land we hold in trust. We are building relationships with local Tribes who have a history tied to this land to learn more about that history and engage in discussions about the most responsible, respectful and cooperative way to steward the land.

The Campbell Farmhouse

Emigrating from Ulster County, Ireland in 1719, the Campbell family first appears in Connecticut in records kept in New London, but the family soon relocated north to Voluntown around the time of its incorporation in 1721. Although the exact date is unknown, the Campbells were among the first European colonists to settle in Voluntown, which had been named for the English volunteer soldiers of King Philip's War. Dr. John Campbell (the second son in the family) is known to have visited Voluntown as early as Nov. 19, 1719, when he and a woman named Agnes Allen got married. The whole Campbell family received a lot of 40 acres, 10 of which they cleared and farmed, and established themselves in the community. In 1723, Robert (the father), and his two oldest sons Charles and John became founding members of the first Presbyterian Church in the town and the state. Robert Campbell passed away a couple years later at the age of 52 in 1725, but the property remained in his family for over a century.

Around 1750, Dr. John Campbell had a house built on the farm -- the very same that still stands at the front of the property today. It features a traditional central chimney with a main hearth in the kitchen and fireplaces in a number of the bedrooms. Dr. John Campbell was the first physician to practice in Voluntown, and many of his descendants carried on in the profession. The house itself offers some clues to Dr. John Campbell’s vocation: the side door and entryway are both unusually wide for colonial houses of the era. Bob Swann believed that may have been the Doctor’s office entrance and waiting area. What is now the bathroom off the hallway is suspected to have originally been the pharmacy. The room across the hall, what is now the Gandhi Reading Room, may have been the original examination room. Former residents have found small antique glass jars buried near the house: old discarded medicine bottles likely from one of the doctors’ practices.

Decades later, people escaping slavery in the South found refuge in the basement of the Campbell Farm as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Although the basement has long since been remodeled, according to a newsletter from the Voluntown Historical Society, there was once “a room behind the chimney in the cellar which several sources report was used as a hiding place for the slaves who came through the underground escape route during the Civil War.”

The Farmhouse has been renovated on numerous occasions, most recently in the mid-90s under the direction of Chuck Matthei, Equity Trust founder and former Executive Director. It is the home of the VPT Caretaker Nancy and her family.

Around 1750, Dr. John Campbell had a house built on the farm -- the very same that still stands at the front of the property today. It features a traditional central chimney with a main hearth in the kitchen and fireplaces in a number of the bedrooms. Dr. John Campbell was the first physician to practice in Voluntown, and many of his descendants carried on in the profession. The house itself offers some clues to Dr. John Campbell’s vocation: the side door and entryway are both unusually wide for colonial houses of the era. Bob Swann believed that may have been the Doctor’s office entrance and waiting area. What is now the bathroom off the hallway is suspected to have originally been the pharmacy. The room across the hall, what is now the Gandhi Reading Room, may have been the original examination room. Former residents have found small antique glass jars buried near the house: old discarded medicine bottles likely from one of the doctors’ practices.

Decades later, people escaping slavery in the South found refuge in the basement of the Campbell Farm as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Although the basement has long since been remodeled, according to a newsletter from the Voluntown Historical Society, there was once “a room behind the chimney in the cellar which several sources report was used as a hiding place for the slaves who came through the underground escape route during the Civil War.”

The Farmhouse has been renovated on numerous occasions, most recently in the mid-90s under the direction of Chuck Matthei, Equity Trust founder and former Executive Director. It is the home of the VPT Caretaker Nancy and her family.

Polaris Action

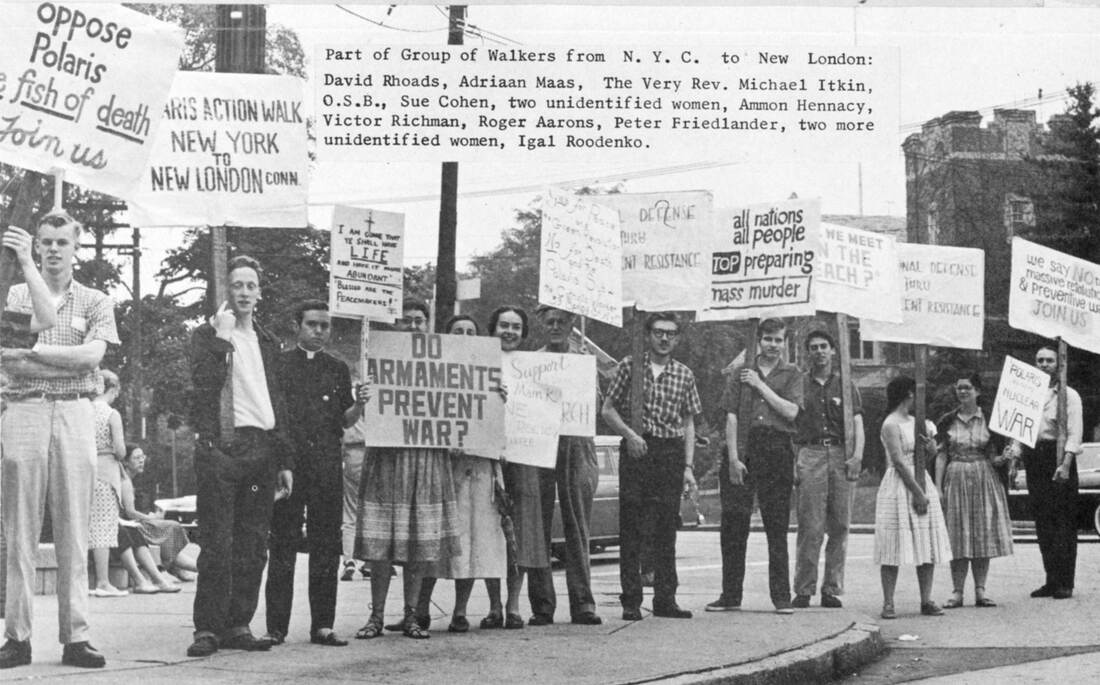

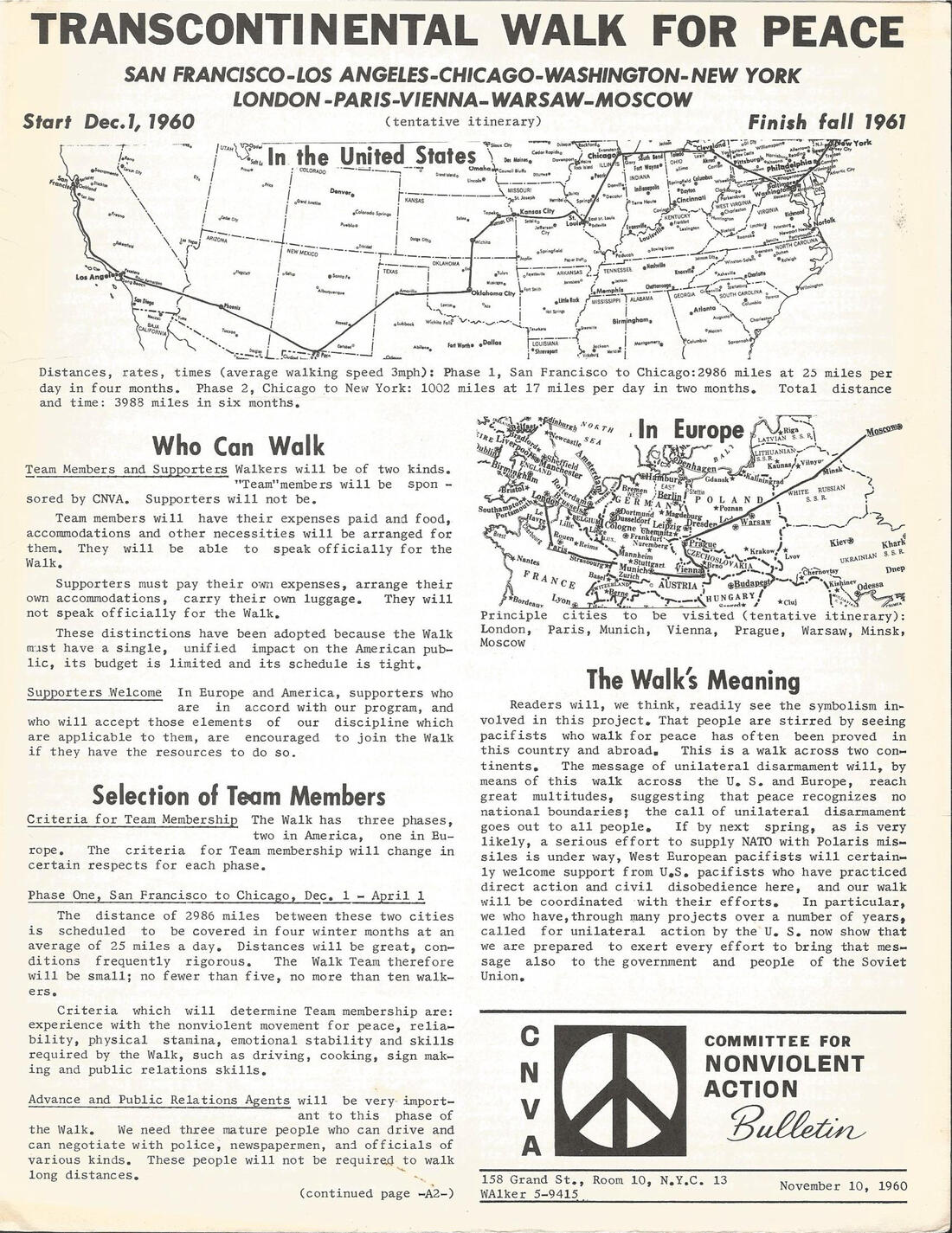

In the summer of 1960, peace activists from around the country gathered in New London, Connecticut to protest the construction of the first nuclear-armed submarines in human history. Conceived primarily by Bradford Lyttle and sponsored by the CNVA, the Polaris Action was a summer-long campaign to “educate Americans to the realities and dangers of the nuclear deterrent policy typified by the Polaris submarines and their deadly cargoes of nuclear missiles” that were being built at General Dynamics/Electric Boat in Groton. Hundreds of participants marched, distributed leaflets, conversed with workers, stood in daily vigils, and made lasting connections with both the local communities and with each other.

"Polaris Action may be thought of as a giant test tube in which are being tried out a great variety of novel peace education activities." The four goals as articulated in the CNVA bulletin "Polaris Action" were:

It was this great experiment in New London and surrounding areas that attracted hundreds of activists to the summer-long action. When the summer ended, however, upon reflection of previous "summer actions" sponsored by the CNVA, many CNVA members including Marj and Bob Swann decided that the old formula “...where we stirred up the community for the summer and then everyone left -- either going to prison or returning home” was neither practical nor morally responsible. So several CNVA members including the Swanns decided to establish a permanent base in southeastern Connecticut to continue to protest the arms race at the largest submarine manufacturing facility in the country, and to promote economic alternatives.

"Polaris Action may be thought of as a giant test tube in which are being tried out a great variety of novel peace education activities." The four goals as articulated in the CNVA bulletin "Polaris Action" were:

- Penetrate public activity by starting conversations about the military industrial complex, the mounting threat of nuclear holocaust, and the ethics of massive retaliation.

- Reach the public by highlighting a diverse range of daring-yet-humble human activities, from attempting to board submarines from small sailboats, to maintaining a friendly and attractive outreach center in a largely hostile environment.

- Gain publicity and distribute literature by cultivating and maintaining good relationships with journalists and other media professionals, while also publishing reports and informational literature from the CNVA itself.

- Create a peace army and the moral equivalent of war by providing peaceful yet vigorous alternatives to military service.

It was this great experiment in New London and surrounding areas that attracted hundreds of activists to the summer-long action. When the summer ended, however, upon reflection of previous "summer actions" sponsored by the CNVA, many CNVA members including Marj and Bob Swann decided that the old formula “...where we stirred up the community for the summer and then everyone left -- either going to prison or returning home” was neither practical nor morally responsible. So several CNVA members including the Swanns decided to establish a permanent base in southeastern Connecticut to continue to protest the arms race at the largest submarine manufacturing facility in the country, and to promote economic alternatives.

New England Committee for Nonviolent Action (NECNVA)

As the summer schedule of protests, outreach attempts, and nonviolence trainings of Polaris Action wrapped up in August of 1960, it was decided that they should continue this work, extended their summer project into a permanent presence. Several participants made plans to stay on a full or part-time basis, joining Bob and Marj Swann (and their children) to continue and expand upon the activities. From “Prospectus for a History of New England CNVA” by Marj Swann: “Moving from the tenement which had been the living quarters for the summer project to a house in Norwich, owned by a supporter, several of the summer participants continued to staff the office, engage in interaction with workers at Electric Boat and sailors at the Navy Base, and began reaching out around the New England Region.” This group named themselves the New England Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA), became an independent affiliate of the national CNVA, and selected Bob and Marj Swann as Co-coordinators for their combined experience as peace activists. As others joined them, Marj Swann writes, “The office in New London was maintained, and the program expanded all around New England, with local groups springing up after the staff had conducted a vigil, a march, or a public education program at local high schools, churches, and universities.”

After a year and a half of sustained work and growth, the New England CNVA decided that they needed more space to effectively hold trainings and workshops, and neither the office in New London nor the house in Norwich, CT would do. A property in a nearby rural area, however, could serve the group’s needs much better. The solution was provided by Mary Meigs, an affluent artist and NECNVA member. The Swanns met Meigs through her then-partner Barbara Deming through Polaris Action in 1960. Deming, a reporter for The Nation magazine at the time, had attended a sixteen-day Peacemaker training session held at their apartment house in New London. On May 8, 1962, for the sum of $17,000, Mary Meigs bought the 40-acre Campbell Farm in rural Voluntown, CT, northeast of New London and Groton. Just a few months later, on August 30, Meigs entered the property into a land trust with Gordon Christiansen and Marjorie Swann. Community land trust pioneer Bob Swann authored the agreement. The first three terms of the agreement are:

Putting the land in trust was both a commitment to the nonviolent economic structures being developed by Bob Swann, and a protection of the land for activists, many of whom were war tax resisters who did not want to own private property that could be seized by the government. The Voluntown Peace Trust was established to be the home of the Community for Non-Violent Action, renamed to reflect the permanence of the group in southeastern Connecticut. Bob, however, wrote the trust agreement to be dynamic and flexible, so that the land could be used for a variety of purposes. Called the “Peace Farm” in those early years, the flexibility written into the original trust agreement proved to have been a wise decision as the priorities, programs, faces and names of the Voluntown Peace Trust changed throughout the decades, while continuing to promote peace.

After a year and a half of sustained work and growth, the New England CNVA decided that they needed more space to effectively hold trainings and workshops, and neither the office in New London nor the house in Norwich, CT would do. A property in a nearby rural area, however, could serve the group’s needs much better. The solution was provided by Mary Meigs, an affluent artist and NECNVA member. The Swanns met Meigs through her then-partner Barbara Deming through Polaris Action in 1960. Deming, a reporter for The Nation magazine at the time, had attended a sixteen-day Peacemaker training session held at their apartment house in New London. On May 8, 1962, for the sum of $17,000, Mary Meigs bought the 40-acre Campbell Farm in rural Voluntown, CT, northeast of New London and Groton. Just a few months later, on August 30, Meigs entered the property into a land trust with Gordon Christiansen and Marjorie Swann. Community land trust pioneer Bob Swann authored the agreement. The first three terms of the agreement are:

- The name of the trust shall be the Voluntown Peace Trust.

- The trust shall be a charitable trust in perpetuity.

- The purpose of the trust shall be the promotion of world peace through educational and other means.

Putting the land in trust was both a commitment to the nonviolent economic structures being developed by Bob Swann, and a protection of the land for activists, many of whom were war tax resisters who did not want to own private property that could be seized by the government. The Voluntown Peace Trust was established to be the home of the Community for Non-Violent Action, renamed to reflect the permanence of the group in southeastern Connecticut. Bob, however, wrote the trust agreement to be dynamic and flexible, so that the land could be used for a variety of purposes. Called the “Peace Farm” in those early years, the flexibility written into the original trust agreement proved to have been a wise decision as the priorities, programs, faces and names of the Voluntown Peace Trust changed throughout the decades, while continuing to promote peace.

Attack on the Peace Farm

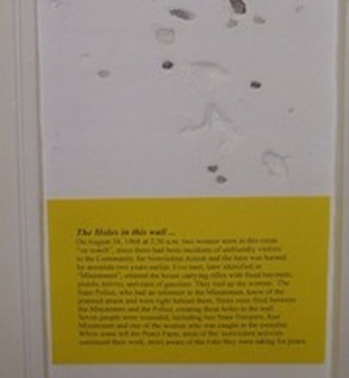

Despite the NECNVA's diligent efforts at peace-building, challenges from oppositionally-minded groups occurred from time to time. These challenges even became violent. In 1966, arson burned down a barn on the Peace Farm. Two years later, in the pre-dawn hours of August 24, 1968, five armed members of the right-wing vigilante group the Minuteman Project stormed the main house with the apparent intention to burn down the rest of the buildings of the farm. Their ultimate goal was to the peace movement here in southeastern CT. The intruders had bound the Farm inhabitants when State Police (tipped off by the FBI) broke in. After a brief and confused firefight -- the evidence of which can still be found embedded in the walls of the Farmhouse -- the Minutemen were subdued.

The Peace Farm's immediate response to the attack is notable: the construction of two new buildings (the A.J. Muste Center and the Swann House), the remodeling of already existing facilities, and a general renewed vigor for peace activism. Rather than focus on the Minutemen attack and other attempts to remove them, many renewed their commitments and threw themselves into the creative work that sprang forth after the dust had settled.

To learn more about the attack, please take a look at this article from CT Explored.

View or download the first-hand report for the New England CNVA, written a month after the attack, here.

The Peace Farm's immediate response to the attack is notable: the construction of two new buildings (the A.J. Muste Center and the Swann House), the remodeling of already existing facilities, and a general renewed vigor for peace activism. Rather than focus on the Minutemen attack and other attempts to remove them, many renewed their commitments and threw themselves into the creative work that sprang forth after the dust had settled.

To learn more about the attack, please take a look at this article from CT Explored.

View or download the first-hand report for the New England CNVA, written a month after the attack, here.

Swann House

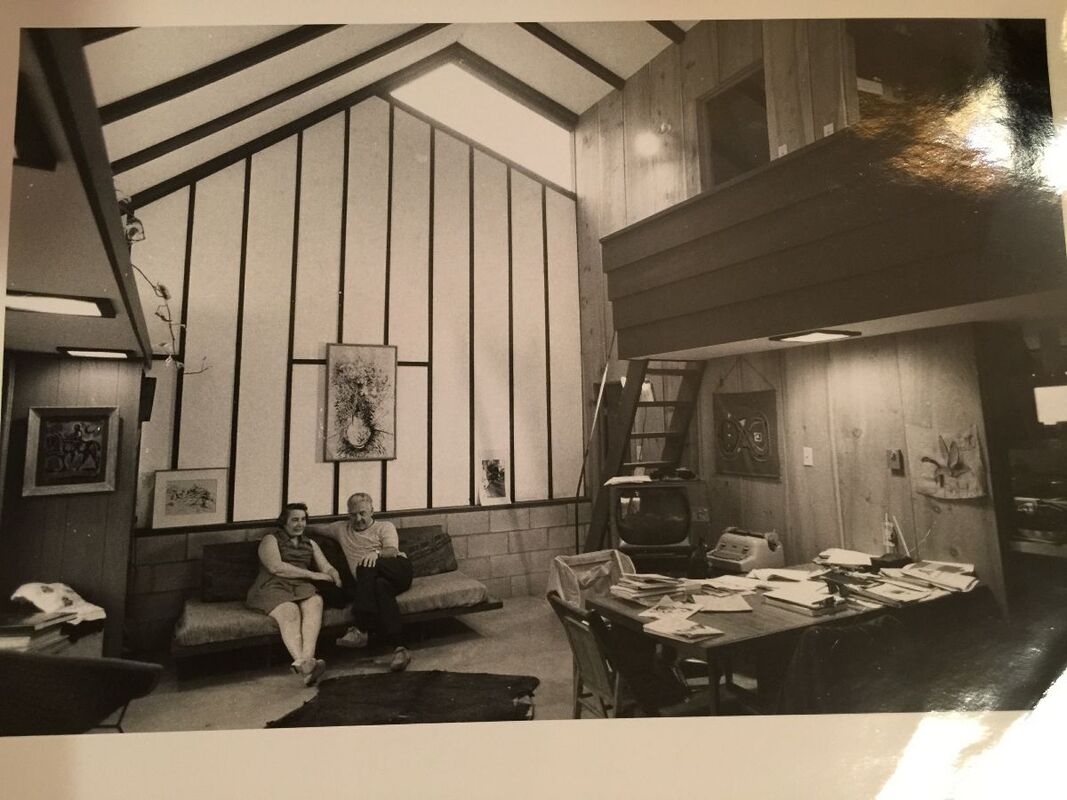

The idyllic Swann House is nestled into a small slope back beyond the VPT Farmhouse and a little west of the A.J. Muste Conference Center. Named after the designer, Bob Swann, the Swann House was the family home of Bob and Marj Swann as well as their children for years.

As a builder for Frank Lloyd Wright in the late 1940s, Bob worked on Wright’s “Usonian” affordable homes in Kalamazoo, Michigan. “Usonia” was Wright’s word for his particular utopian vision of a new beautiful, ethical, middle-class lifestyle in the United States -- shaped in large part by his simple but bespoke homes. Inspired by the renowned architect, Bob tried his own experiments in making beautiful, affordable housing. The Swann House, built in 1966 by Bob and the help of volunteer labor, and with materials totaling just $3000, is one such example.

After the Swann family moved away in 1971, the house has been used by VPT for other purposes. Over the decades, Swann House has sheltered innumerable guests for conferences and retreats, as well as women and children seeking safety from unsafe domestic environments. As a unique building designed by a Frank Lloyd Wright builder, Swann House also holds value as an example of bespoke affordable home design, of Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy and influence, and of developments in the broader history of modern architecture.

Recently, we here at VPT have been renovating the upper loft area in order to better comply with fire codes, to respond to changes in how we use the space, and to have the house better fit with the land. The renovated loft will contain two rooms, both with access to a new back deck. As the back of the house is partially set into a slope, the deck and accompanying ramp will bridge the small gap between the top of the slope and the house itself, giving the two loft rooms a safer "ground floor" point of egress, and generally providing greater accessibility. These changes are being added in such a way as to improve the house's aesthetic cohesion with the shape of the surrounding land while still maintaining the original spirit of the structure.

In October 2020, while some of the other renovation plans were paused, volunteers gave Swann House a fresh paint job. With the new coat of paint, Swann House looks ready to finish those renovations and open back up to guests soon.

These renovations have not been cheap, and due to the pandemic, VPT lost nearly all of its rental income in 2020. If you can, please consider donating to us to help offset the costs of these renovations. To give a tax-deductible gift to the Voluntown Peace Trust, visit our donations link here.

As a builder for Frank Lloyd Wright in the late 1940s, Bob worked on Wright’s “Usonian” affordable homes in Kalamazoo, Michigan. “Usonia” was Wright’s word for his particular utopian vision of a new beautiful, ethical, middle-class lifestyle in the United States -- shaped in large part by his simple but bespoke homes. Inspired by the renowned architect, Bob tried his own experiments in making beautiful, affordable housing. The Swann House, built in 1966 by Bob and the help of volunteer labor, and with materials totaling just $3000, is one such example.

After the Swann family moved away in 1971, the house has been used by VPT for other purposes. Over the decades, Swann House has sheltered innumerable guests for conferences and retreats, as well as women and children seeking safety from unsafe domestic environments. As a unique building designed by a Frank Lloyd Wright builder, Swann House also holds value as an example of bespoke affordable home design, of Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy and influence, and of developments in the broader history of modern architecture.

Recently, we here at VPT have been renovating the upper loft area in order to better comply with fire codes, to respond to changes in how we use the space, and to have the house better fit with the land. The renovated loft will contain two rooms, both with access to a new back deck. As the back of the house is partially set into a slope, the deck and accompanying ramp will bridge the small gap between the top of the slope and the house itself, giving the two loft rooms a safer "ground floor" point of egress, and generally providing greater accessibility. These changes are being added in such a way as to improve the house's aesthetic cohesion with the shape of the surrounding land while still maintaining the original spirit of the structure.

In October 2020, while some of the other renovation plans were paused, volunteers gave Swann House a fresh paint job. With the new coat of paint, Swann House looks ready to finish those renovations and open back up to guests soon.

These renovations have not been cheap, and due to the pandemic, VPT lost nearly all of its rental income in 2020. If you can, please consider donating to us to help offset the costs of these renovations. To give a tax-deductible gift to the Voluntown Peace Trust, visit our donations link here.