|

As our country continues to reckon with the genocidal campaigns and other historical violence against Native peoples since the colonization of this land, we at the Peace Trust have also been reckoning with the violent and unjust legacy we unknowingly inherited by moving to Voluntown almost sixty years ago. Voluntown was originally named for the colonists who volunteered to attempt genocide on a Wampanoag-led Native coalition in what has become known as King Philip’s War (1675-1678).

When Wamsutta wrote the following speech, it was only two years after the American Indian Movement had started (and two years after Dr. King’s assassination), and the residential school system was still ongoing. Large swaths of white America were still unwilling to reconsider the historical myths they had been taught as children, and Wamsutta’s speech was never delivered to its intended audience. Now, 52 years later, as we continue to remove or recontextualize statues of colonizers and slaveowners, and as state governments (including Connecticut’s) establish the mandatory teaching of Native history in public schools, perhaps this country is finally ready to learn its true history, to correct past wrongs, and to build a truly just society. “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG” To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970 ABOUT THE DOCUMENT: Three hundred fifty years after the Pilgrims began their invasion of the land of the Wampanoag, their "American" descendants planned an anniversary celebration. Still clinging to the white schoolbook myth of friendly relations between their forefathers and the Wampanoag, the anniversary planners thought it would be nice to have an Indian make an appreciative and complimentary speech at their state dinner. Frank James was asked to speak at the celebration. He accepted. The planners, however, asked to see his speech in advance of the occasion, and it turned out that Frank James' views — based on history rather than mythology — were not what the Pilgrims' descendants wanted to hear. Frank James refused to deliver a speech written by a public relations person. Frank James did not speak at the anniversary celebration. If he had spoken, this is what he would have said: I speak to you as a man -- a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction ("You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!"). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so. It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt's Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people. What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called "savages." Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other "witch." And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the "savage" and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again. The white man used the Indian's nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman -- but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we Indians have been termed "low man on the totem pole." Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons. What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as "civilized" people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags'] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty. History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood. The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his "savageness" has boomeranged and isn't a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian's temperament! High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians! Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently. Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting We're standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us. We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail. You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian. There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We're being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours. Wamsutta September 10, 1970 -- Take Action See how you can support the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative: http://www.narragansettfoodsovereignty.org/ Sign the petition and see what else you can do to stop Line 3 and support Water Protectors: https://www.stopline3.org/biden — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source James, Wamsutta (Frank B.). “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG.” United American Indians of New England. http://www.uaine.org/suppressed_speech.htm Too often around this time of year, we tend to only hear two types of stories of Native Americans: colonialist myths evoking racist stereotypes and true stories of immense historical trauma. The former continues to cause harm by dehumanizing contemporary Native peoples into caricatures. The latter is important to teach and understand, but also often fails to tell what happened to the survivors of colonial genocidal acts and their descendants. Especially in southern New England, many of those descendants continued to carry on Indigenous practices, often balancing traditional ways with the demands of living under an alien colonial government and, later, within a “modern” nation-state that formed over them. Despite the combination of economic, cultural, and political pressures that disparaged Native traditions and sought to push Native Americans into conformity with the white social hegemony, some Indigenous people were able to pass along such traditional knowledge to the next generation.

The Dovecrest Restaurant was the result of one of those Native families who managed to balance between old and new ways. Founded by Eleanor (Pretty Flower, 1918-2019) and Ferris Babcock Dove (Chief Roaring Bull, 1915-1983), both members of the Narragansett/Niantic Tribal Nation, Dovecrest was a family-operated restaurant that came to be known for its unique offering of Indigenous cuisine. From 1963 to 1984, the Doves and their extended family promoted Narragansett/Niantic culture through Native culinary arts. Eleanor herself had grown up in a family of chefs. But Dovecrest was more than just a restaurant. The main dining room of the restaurant could seat up to 90 people, and the restaurant itself became a cultural center for Narragansett/Niantic people. In the late ‘60s, the Doves invited fellow Narragansett/Niantic member Red Wing (Mary E. Congdon, 1896-1897) to live at Dovecrest. Red Wing was the co-founder and curator of the original Tomaquag Museum and an internationally known storyteller and keeper of cultural knowledge for the Narragansett/Niantic and Wampanoag Tribes. When the original Tomaquag Museum in Ashaway closed in 1969, it was relocated to Dovecrest and so well integrated into the restaurant that soon, Dovecrest and Tomaquag became effectively synonymous. Once Red Wing made the move, she and the Doves hosted several Indigenous thanksgivings at Dovecrest throughout the year. They would invite Native and non-Native peoples alike to join together to celebrate and learn more about the Indigenous culture of their area — something that almost never happened outside of powwows. The restaurant also sat adjacent to the Doves’ home, where the western part of the building was designated as the Dovecrest Trading Post: a gift shop selling “a variety of Indigenous art, clothing and jewelry from all over the United States.” Below, we have an excerpt from the Tomaquag Museum’s blog Belongings about the Dovecrest Restaurant. Check the source below the excerpt for the link to the full blog post, which includes additional details on the Dove family, Red Wing, the thanksgiving celebrations at Dovecrest, and more. On the Belongings blog page, you will also find four special Indigenous recipes! — …Initially, when the Doves had opened Dovecrest Restaurant the menu offered “standard steakhouse fare,” which was typically considered main dishes such as beef steaks, pork chops chicken and seafood with sides of vegetables and hearty soups, stews and chowders- your typical Yankee style meat and potatoes type restaurant. (This was very much the backbone of the Dovecrest Restaurant for its entire existence.) It wasn’t until a few years after Dovecrest was in operation that patrons of the restaurant noticed that the Doves were preparing different meals for their children in the room behind the kitchen. These meals comprised of wild meats, or “game” meats. Soon, customers were asking that if instead of ordering the standard steakhouse fare, they were able to order dishes such as venison stew and creamed dried cod. Venison was of course an important staple for the Indigenous people throughout time on both the North and South American continents. Venison was essential to both survival and culture as the white tailed deer provided not only food, but clothing, adornments and tools. Ferris, in his own words, “When I was growing up in Charlestown, we depended on food like venison. We would have feasts of venison steaks, oysters we pulled from the bay, Johnnycakes and potatoes. This was 1930, and only the poor people were eating that stuff. Now it’s a delicacy. Isn’t it funny how things change?” And things did change. Slowly, but surely the Doves began incorporating wild game and other traditional Indigenous recipes, some that Eleanor had learned from her father, Joseph Spears, Sr. (who had also been a chef at the University Club in Providence) into the menu. These wild games were then appeared on for special occasions or whenever wild game or shellfish happened to be available and/or in season. Eleanor said she tried to always keep one game dish on the menu, but it was often difficult to have a steady stock on hand. Many of the wild game was procured locally, from friends and neighbors who hunted, but for other types of game, such as bison they had to rely on private, out of state distributors such as ranch in Western Massachusetts or Iron Gate Products in Manhattan. As the specialty wild game dishes began appearing on the menu, word traveled fast and Dovecrest started to become well known as a restaurant that was not only owned and operated by Indigenous people-at that time the only such establishment east of the Mississippi River-but Indigenous people who were also serving traditional Indigenous foods in this small, out of the way place in rural Exeter. One of the dishes which became a specialty at Dovecrest was a “briny fresh clam chowder” which were of course locally sourced from Narragansett Bay and other locations in Rhode Island and were shucked by Ferris every Friday and according to Eleanor “does it faster than anyone I’ve ever seen.” In addition to the venison stew, creamed dried cod and briny; or Rhode Island style clam chowder, Dovecrest entrees on the menu could include bison steak and pie, quahog pie, venison steak and pie, rabbit stew, squirrel pie, racoon pie, bear, elk, succotash, Indian pudding-and what they became most famous for, Johnnycakes. Johnnycakes, or “Journey cakes” as they were known during the contact (Colonial) period, were a traditional staple of Indigenous people throughout North America and the Caribbean before the invasion of Europeans and was quickly adopted by European colonists and anglicized into what we know now as Johnnycakes. Usually (but not always) they are made out of ground white flint maize, water, milk and butter, salted with a little sugar and cooked on a griddle until deep golden brown, Johnnycakes then became a staple of European colonial life and like many of the plants and animals in the Americas slowly had their Indigenous roots erased through time. Johnnycakes were served plain, as is, or with additional local, seasonal ingredients such as maple syrup, blueberries and cranberries. Over the years as their reputation grew, Dovecrest Restaurant was recognized in many ‘Best of” guides, winning rave reviews for their Johnnycakes as often the best in the state (and even some said New England) appearing in a New York Times article ‘Cuisine as American as Raccoon Pie’ in December 9, 1981 and even winning a 1982 Ocean Spray Cranberry Salute to American Food Award in Pittsburgh in addition to a USA Today article, ‘On The Menu Succotash and Venison.’ All of the awards and accolades were hard earned and well deserved for Dovecrest Restaurant, especially the Dove matriarch Eleanor, who was the primary chef and ran the kitchen. According to Ferris, “she’s the cook and I’m the waiter.” In addition to Ferris’ clam shucking, bartending and wait duties, Dovecrest Restaurant and Trading Post was a family operation and relied on the help of close family members such as their children, Mark, Paulla, Dawn and Lori and later granddaughters Elisabeth Dove (Manning) and Lorén Wilson (Spears) as well as Eleanor’s father Joseph Spears, Jr. and Ferris’ mother Mimi Babcock Dove as well as other extended family members and local tribal members… -- Take Action See how you can support the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative: http://www.narragansettfoodsovereignty.org/ Sign the petition and see what else you can do to stop Line 3 and support Water Protectors: https://www.stopline3.org/biden — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source “From the Archives: Dovecrest Restaurant & Thanksgiving.” Tomaquag Museum. 26 November 2020 [Accessed 17 November 2021]. https://www.tomaquagmuseum.org/belongingsblog/2020/11/2/dovecrest-restaurant-and-thanksgiving — Further Resources Here is a podcast episode for all ages about Wampanoag and Narragansett thanksgiving traditions featuring Loren M. Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum: “Giving Thanks!” Time For Lunch podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/giving-thanks/id1504928110?i=1000499993371 Today is Veterans Day here in the United States — better known as Armistice Day or Remembrance Day throughout much of the world. In the past, we have used this holiday to draw comparisons between the United States and much of the rest of the world. But this year, we are turning inward to examine how the US military has affected one specific racial category within the United States itself: Native Americans.

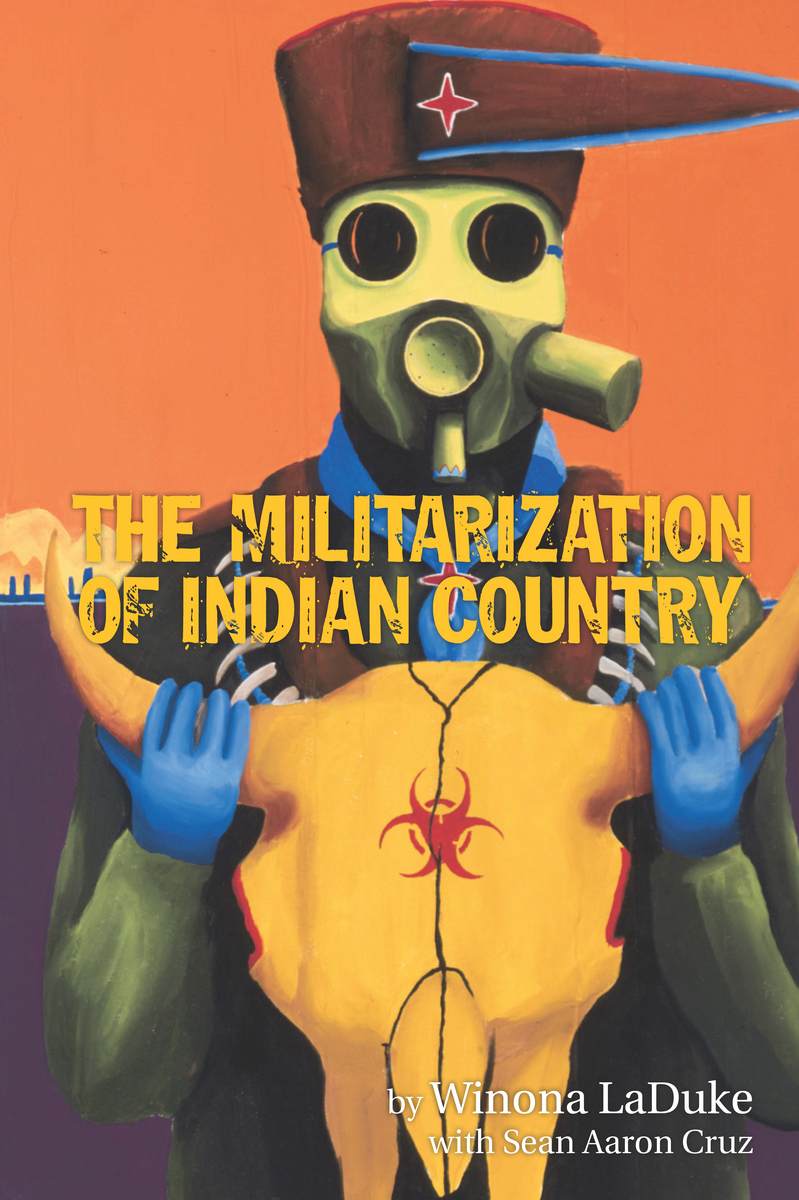

Winona LaDuke is a Native American Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) activist-economist who is known for her involvement in many large projects: the White Earth Land Recovery Project, which reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people; Honor the Earth, a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues; and most recently, the Line 3 pipeline protests that seek to prevent enormous ecological disasters in Native lands. In her 2013 book The Militarization of Indian Country, LaDuke explores several dimensions of the intersection of Native peoples and the US military, from historical seizures of Native land by the military, to contemporary post-traumatic stress disorder of Indigenous veterans, to glimmers of hope and peace in the future. As LaDuke alludes in these excerpts, the relationship between the US military and Native American peoples is complex and fraught. On the one hand, the military offered to many Native Americans a ticket out of desperate circumstances: the impoverished reservation, the horrifying residential schools, the abusive adoptive family, and other awful situations to which so many Native people had been subjected. On the other hand, it was precisely the US military that drove so many recent Native ancestors from their homes, violently fractured countless Native communities and families, and then appropriated Native names to describe the US military’s bases (all on occupied land), weapons and vehicles (inanimate death machines), and most problematically, enemies (nameless, faceless, irrational “Others”). — [...] I do not hate the military. I do despise militarization and its impacts on men, women, children, and the land. The chilling facts are that the United States is the largest purveyor of weapons in the world, and that millions of people have no land, food, homes, clean air or water, and often, limbs, because of the military funded by my tax dollars. Countless thousands of square miles of Mother Earth are already contaminated, bombed, poisoned, scorched, gassed, bombarded, rocketed, strafed, torpedoed, defoliated, land-mined, strip-mined, made radioactive and uninhabitable. I despise militarization because those who are most likely to be impacted or killed by the military are civilian non-combatants. Since the Second World War, more than four fifths of the people killed in war have been civilians. Globally there are some 16 million refugees from war… I decided to write this book because I am awed by the impact of the military on the world and on Native America. It is pervasive. Native people have seen our communities, lands and life ways destroyed by the military. Since the first European colonizers arrived, the US military has been a blunt instrument of genocide, carrying out policies of removal and extermination against Native Peoples. Following the Indian Wars, we experienced the forced assimilation of boarding schools, which were founded by an army colonel, Richard Pratt, and which left a history of transformative loss of language and culture. The modern US military has taken our lands for bombing exercises and military bases, and for the experimentation and storage of the deadliest chemical agents and toxins known to mankind. Today, the military continues to bomb Native Hawaiian lands, from Makua to the Big Island, destroying life. The military has named us and claimed us. Many of our tribal communities are named after the forts that once held our people captive, and in today’s military nomenclature Osama bin Laden, the recently killed leader of al Qaeda, was also known as “Geronimo EKIA” (Enemy Killed in Action). Harlan Geronimo, an army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam and is the great grandson of Apache Chief Geronimo, asked for a formal apology and called the Pentagon’s decision to use the code name Geronimo in the raid that ended with al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden’s death, a “grievous insult.” He was joined by most major Native American organizations in calling for a retraction and apology. The Onondaga nation stated, “This continues to personify the original peoples of North America as enemies and savages. . . . The US military leadership should have known better.” The analogy from a military perspective is interesting. At the time of the hunting down of Geronimo, over 5,500 military personnel were engaged in a 13-year pursuit of the Apache Chief. Geronimo traveled with his community, including 35 men and 108 women and children, who in the end surrendered in exhaustion and were met with promises that were never fulfilled. It was one of the most expensive and shameful of the Indian Wars… The military, it seems, is comfortable with this ground. Indeed, Native nomenclature in the US military is widespread. From Kiowa, Apache Longbow and Black Hawk helicopters to Tomahawk missiles, the machinery of war has many Native names. (The Huey helicopter―Bell UH-1 is the Iroquois, and the Sikorsky helicopters are also known as Chickasaw, Choctaw and Mohave helicopters.) As the Seventh Cavalry invaded Iraq in 2003 in the “Shock and Awe” campaign that opened the war, one could not help note that this was the name of the cavalry division that had murdered 300 men, women and children at Wounded Knee. Yet, despite our history and the present appropriation of our lands and culture by the military, we have the highest rate of military enlistment of any ethnic group in the United States. We also have the largest number of living veterans out of any community in the country. We have borne a huge burden of post traumatic stress disorder among our veterans, and continue to feel this pain today, compounded by our own unresolved historic grief stemming from colonization. In this book, I consider the scope of our historic and present relationship with the military and discuss economic, ecological and psychological impacts. I then examine the potential for a major transformation from the US military economy that today controls much of Indian Country to a new community-centered model that values our Native cultures and traditions and honors our Mother Earth… -- Take Action Sign the petition and see what else you can do to stop Line 3 and support Water Protectors: https://www.stopline3.org/biden While on the topic of Indigenous issues, there is a renewed campaign to free Native American activist Leonard Peltier from prison. Read about his story and, if you are moved to do so, support the Leonard Peltier Freedom Ride 2021 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source LaDuke, Winona. The Militarization of Indian Country. Michigan University Press, 2012. — Further Resources Honor the Earth: a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues. https://www.honorearth.org/ White Earth Land Recovery Project: reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people. https://www.welrp.org/ Fourteen months ago, we told the story of the 1992-1995 grassroots campaign that successfully removed the statue of John Mason who led the massacre of the Pequot village in Mystic in 1637 from its original location on the site of the massacre. When we told that story, the country was grappling with the legacy of public statues that celebrate historical violence against people of color in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. In the time since then, there have been further developments with the fate of John Mason’s statue. In Windsor, where the statue was relocated in 1996, the town council decided in January 2021 to move the statue from its prominent position on Palisado Green to an accessible site at the nearby Windsor Historical Society, where new plaques would provide more complete context for students and other members of the public. And in Hartford, in June of this year, the legislature included provisions in the state’s 2021-2022 budget to remove their own John Mason statue from the state Capitol building’s facade. However, in part due to some public resistance to the removal and in part due to the unexpectedly high cost of the project, the plans to remove the statue from the Capitol have been put on hold. Some of the opposition have argued that to remove the statue is to lose an important part of Connecticut history, and that “The historic preservation of history cannot be changed just because someone doesn’t like the moment.” But that is patently false. History is not a collection of immutable facts, but an ever-developing process of understanding the past. Moreover, as our story below shows, the movement to remove problematic statues is not new or simply part of our current “moment,” but has been a long process with roots as far back as the 1970s. And as this movement continues to develop and find success, previously buried parts of our state’s history will be revealed, new understandings of our state’s peoples will form, and we will all be better for it.

— (Originally posted on September 10, 2020: https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/posts/10158463469292978/) After decades of Native and allied activists raising the consciousness and educating the public about the myths and truths about early European colonization of the Americas, starting in June of this year, Christopher Columbus statues started to topple all across the United States. Less than three decades ago, such a trend would have been unimaginable. In fact, during the 1992 “celebrations” of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ first transatlantic voyage, activists in eastern Connecticut focused their efforts not on the removal Columbus statues, but on another target: Captain John Mason, “Conqueror of the Pequots.” The colonial leader’s 9-foot tall, 2-ton heroic bronze statue stood for more than a century in Mystic, CT over the place where he led the massacre of 400-700 Pequot people of all ages and genders, mostly noncombatants. In the end, the Pequot leadership was assassinated; the Pequot name was forbidden; and the roughly 200 survivors were hunted down and either taken in by their former Native rivals, the Mohegans and the Narragansetts, or else enslaved by the English and sold to far away places. In simplified terms, the Pequot survivors who were taken by the Mohegans to the west became the Mashantucket Pequots, and the ones taken by the Narragansetts to the east became the Eastern and Eastern Paucatuck Pequots. (To learn the story of the massacre itself, please visit the websites for the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center as well as the Battlefields of the Pequot War project.) The efforts to remove or relocate the John Mason statue that began in 1992 was not the first such attempt. Years earlier, starting in the 1970s and continuing into the mid 1980s, Raymond Geer of the Paucatuck Eastern Pequots led an attempt to remove the Mason statue, but did not gain much traction at the time. The Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Tribal Nation was only granted federal recognition in 1983, very narrowly having almost lost the entirety of their reservation land to the State of Connecticut a few years earlier. The Eastern Pequots and Paucatuck Eastern Pequots, two separate groups, unified and became recognized by the Department of Interior in 2002 -- only to have that recognition revoked in 2005 due to fears of a new possible casino on reservation land. In the 1970s-80s, indigenous groups such as the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the United American Indians of New England began publicly challenging the racist assumptions inherent to Columbus Day and Thanksgiving, but the full effects of those consciousness-raising campaigns would not be felt for years. In this period, the Pequot population that lived on reservation land was growing but still quite tiny. Geer had few allies to turn to when he made his attempts against the Mason statue, and this first attempt failed. But by the 1990s, changes in the broader culture were apparent. The recently federally-recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation completed phase 1 of the planned Foxwoods Resort Casino in 1992. Columbus Day “celebrations” were held across the country for the 500th anniversary just as more Americans than ever before started to realize the problems with honoring a figure like Columbus. And in that same year, Wolf Jackson of the Eastern Pequots asked the Southeastern Connecticut Coalition for Peace and Justice (SCCPJ), which had initially formed to oppose the First Gulf War, to help renew the campaign to remove the Mason statue. This time, the effort was built on alliances. The SCCPJ itself was composed of diverse groups including the Catholic Diocese of Norwich, Veterans for Peace, and the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. Wolf Jackson and the SCCPJ circulated a petition that summer about removing the statue, which collected over 900 names agreeing that the statue is “an inappropriate commemoration of a massacre of over 700 men, women, and children and represents a distortion of history which is extremely offensive to many citizens, particularly Native Americans.” At first, none of the councils of the three Pequot tribal nations would officially endorse the move, despite the common opinion of Pequots that the statue was offensive. Complicating matters was the bitter rivalry between the Pequot tribes, especially between the darker-skinned Eastern Pequots and the lighter-skinned Paucatuck Eastern Pequots, that made forming a united front very difficult. But after two years of building alliances and healing old wounds, cultivating community support and exploring many possible options for compromise, the demand to remove the statue spread to more people and became impossible to ignore. The petition was presented to the Town of Groton, where there were allies on the Town Council. Despite the growing demand to remove the statue, a descendant of John Mason spoke in favor of keeping the statue on the massacre site. By then, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, suddenly a big player in Connecticut politics, had ended their initial silence and proposed not just the removal of the statue, but its relocation to the in-development Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. The Mashantucket Pequots even offered to pay for the statue’s removal, relocation, and storage while the museum was being built. The Town of Groton ultimately voted to follow the Mashantucket Pequot proposal, but the lawful owner of the statue, the State of Connecticut, instead moved it to Windsor, Connecticut, one of the towns John Mason founded. In May 1995, supporters of the campaign gathered at the statue’s location to witness its removal. The ceremony was one of Native unity and community power. Present were Pequots from all three tribal nations; Mohegans and Narragansetts descended from the old Pequot enemies; and members of SCCPJ and the neighborhood community. Rick Gaumer, SCCPJ member and a former resident of the Voluntown Peace Trust in the late 1970s, was in attendance at the ceremony. After working for the removal of the statue, he discovered that he was a descendant of Nicolas Olmstead, a soldier who followed John Mason’s command to burn the village. Rick spoke at the ceremony, describing how the burning of villages in Vietnam had made him a pacifist, bringing him to this place. A year later, the town of Windsor celebrated the “return” of their hometown founder. It was a solution that Wolf Jackson said he “could live with.” Now, the old question of what to do with the problematic statue is haunting Windsor. The statue has been a target of vandalism since it was moved to Windsor, and the most recent act of vandalism occurred within the last few months. On September 7 of this week, the Windsor Town Council voted 5-4 to take it down from its prominent position at the Palisado Green and move it to the Windsor Historical Society -- a decision difficult to imagine without the momentum of the many recent successes taking down Columbus statues right behind it. When Raymond Geer made his attempt to remove the John Mason statue in the 1970s and 80s, perhaps his society was not quite ready to hear him out. But within a decade or so, things in eastern Connecticut began to change. The 500th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas heightened the attention and scrutiny paid to colonial history, and raised consciousness of the European invasion that led to the genocides of indigenous peoples. The successes of the Mashantucket Pequots and other Native groups along with the 500th Columbus anniversary created a unique cultural moment in eastern Connecticut in the early 1990s -- a moment that Wolf Jackson and the SCCPJ used effectively to complete their campaign. The 400th anniversaries of the founding of Jamestown (1619) and the landing of the Mayflower (1620) have similarly focused some people’s attention on the violent realities of White supremacy and capitalism, bringing coalitions of people together who are now removing statues and dispelling historical myths. Like Wolf Jackson and the SCCPJ, our present challenge is to use our own cultural moment -- and together create a more just society. — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “1637 - The Pequot War.” The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. https://www.colonialwarsct.org/1637.htm Gaumer, Rick. “Reminder of the violence that founded a nation.” The Day. July 20, 2020. https://www.theday.com/article/20200720/OP03/200729992 Goode, Steven. “State will move John Mason statue and take it to historical society; monument honored colonial leader of attack on Pequots.” Hartford Courant. September 9, 2020. https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/city-officials-discuss-removal-of-controversial-statue-in-windsor/2301219/ “The History of the Pequot War.” Battlefields of the Pequot War. http://pequotwar.org/about/ Libby, Sam. “For one Pequot, statue’s removal is vision come true.” Hartford Courant. May 11, 1995. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1995-05-11-9505110513-story.html Libby, Sam. “THE VIEW FROM: MYSTIC; An 1889 Statue Leads to Second Thoughts About a Battle in 1637.” The New York Times. November 29, 1992. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/29/nyregion/the-view-from-mystic-an-1889-statue-leads-to-second-thoughts-about.html Libby, Sam. “Where a Statue Stands Is State’s Decision.” The New York Times. July 24, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/24/nyregion/where-a-statue-stands-is-states-decision.html Louie, Vivian and Sam Libby. “Groton Statue Stands at Center of Debate.” Hartford Courant. October 4, 1992. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1992-10-04-0000111690-story.html “The Pequot War.” The Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Tribal Nation. https://www.mptn-nsn.gov/pequotwar.aspx Purdy, Erika M. “Windsor council votes to remove controversial statue from Palisado Green.” Journal Inquirer. September 9, 2020. https://www.journalinquirer.com/towns/windsor/windsor-council-votes-to-remove-controversial-statue-from-palisado-green/article_6c12a68c-f2b0-11ea-a772-6fc4cbb99145.html Shanahan, Marie K. “John Mason Statue has a Homecoming.” Hartford Courant. June 1996. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1992-10-04-0000111690-story.html “Town Officials Discuss Removal of Controversial Statue in Windsor.” NBC Connecticut. July 12, 2020. https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/city-officials-discuss-removal-of-controversial-statue-in-windsor/2301219/ Underhill, John. “Newes from America; Or, A New and Experimentall Discoverie of New England; Containing, A Trve Relation of Their War-like Proceedings These Two Yeares Last Past, with a Figure of the Indian Fort, or Palizado” (1638). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 37. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/37 — Further Resources Hallenbeck, Brian. “A second Mason statue to be moved to less prominent site.” The Day. 10 June 2021 [Accessed 3 November 2021]. https://www.theday.com/article/20210610/NWS01/210619927 Stuart, Christine. “John Mason Statue at Capitol Gets Temporary Reprieve.” MSN CT. 1 October 2021 [Accessed 3 November 2021]. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/john-mason-statue-at-capitol-gets-temporary-reprieve/ar-AAP3mrn Goode, Steven. “Council vote to fund John Mason statue move reopens disagreement.” Hartford Courant. 20 January 2021 [Accessed 3 November 2021]. https://www.courant.com/community/windsor/hc-news-windsor-john-mason-statue-update-20210120-ylwwscrq7ra43nag7c2pynyufi-story.html |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed