|

(This week’s post is a condensed version of an essay Marco Frucht wrote in 2009 for the University of Connecticut. You can read the full version at his blog: http://muffinbottoms.org/?p=395)

Committee for Nonviolent Action and the Highlander Center share so much in common throughout their distinct experiences in Connecticut and Tennessee respectively, that this essay will only attempt to survey the ideas and events around one important year in their common history; 1960. CNVA was founded nationally in 1957 by A.J. Muste, a veteran labor agitator and Christian pacifist and David Dellinger who had been a conscientious objector since at least as early as World War II. Many chapters were started around the country in the next few years, including the New England CNVA which began in 1960. Today, the New England CNVA is known as the Voluntown Peace Trust. Highlander Folk School was established in the 1930s by Myles Horton to train labor and Civil Rights activists. Nonviolence and music were always common themes there but didn’t come into primary focus until the late 50s and early 60s. Some of this was at the inspiration of Mohandas Gandhi because he had taught non-violent direct action as a tool the people in India could use in their struggle against British rule. Horton says the following about music in the movement: “Song, music and food are integral parts of education at Highlander. Music is one way for people to express their traditions, longings and determination. Many people have made significant contributions to music at Highlander. In the early days, Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger came to visit. Later on, Frank Hamilton and Jack Elliott spent time with us. More recently, the Freedom Singers, Bernice Reagon and Sweet Honey in the Rock, as well as Highlander’s former codirector, Jane Sapp, have been regular contributors. There were also those who stayed at Highlander for longer periods, such as Lee Hays, one of the original Almanac Singers, and Waldemar Hille.” One of the times Martin Luther King, Jr., was at Highlander, he was a keynote speaker at their seventh annual College Workshop, April 15, 1960. In this speech he called for a nationwide campaign of selective buying and said he wished for people to hold their money from places all over the south that were violent and racist. “There is another element that must be present in our struggle that then makes our resistance and nonviolence truly meaningful. That element is reconciliation. Our ultimate end must be the creation of the beloved community.” 1960 was a very busy year for Folksinger Pete Seeger too, singing everywhere from the Nevada Test Site to protests of the Polaris submarine launchings in Groton, CT., not to mention making all the time necessary to coproduce television pilots with his wife Toshi that eventually became the weekly show Rainbow Quest on WNJU-TV in New York and New Jersey. Marj Swann printed the following in Polaris Action Bulletin #4. 13jun60: “Four Canadian young people asked why Americans are so afraid to speak out against Government policies or to be different. At the festival, Pete Seeger, who had visited the New London office earlier, dedicated “The Hammer Song” to the Satyagraha, a sloop named after some of Gandhi’s famous nonviolent direct actions.”[...] When Seeger wasn’t singing in Connecticut, home in Upstate New York on the Hudson river, or playing a gig somewhere else in the world he was at the Highlander Folk School. (Over the years, Highlander came to be called the Highlander Research and Education Center). Highlander was where Guy Carawan spent years teaching countless people to sing many songs, but notably “We Shall Overcome.” Nashville Public Library has a Photograph of a meeting at Fisk University, where Guy Carawan leads song on his guitar, April 21, 1960. That song was fast becoming a staple for folksingers all over America. It’s still very popular today. So who taught Carawan to play that song? Pete Seeger of course; but who taught it to Pete? Zilphia Horton showed him the tune as her all-time favorite song when she was Highlander’s music director. Where the song originally came from and how it changed over time would easily be a good topic for anyone’s PHD thesis, because it changed so much over the decades like a well worn shoe; but Pete Seeger is credited with changing “I” to “We” and helping spread the song all over the deep south. Many consider that song to be the earliest primary link between the following movements, Abolition, Labor, Civil Rights, Peace, No-Nukes, Anti-Globalization and all points in between. Some could even argue Pete Seeger himself was that link. Nevertheless, that song was being taught at CNVA, Highlander, and anywhere else people were discussing American social justice in 1960[...] What was happening in New London County, that would call for songs, and people like Carawan, Seeger and Joan Baez to drop in often? Polaris[...] New London County is very close to New York and Boston but it’s also just a short drive from Newport. Of course that means the annual Jazz fests and Folk fests can be an easy visit for someone with a local gig; but oftentimes they would stay there at CNVA instead of booking a hotel room. And of course that made them an excellent guest teacher for a day or three. While the members of Polaris Action were at the Newport Folk festival, they and Pete Seeger brought the project to the attention of Joan Baez, whom they had heard was a pacifist. That was the first time that Joan sang at the festival, and her extraordinarily clear, wide-ranged, powerful and moving soprano voice propelled her into the stature of perhaps the country’s premiere folk singer[...] Nonviolence and music carry on year after year helping maintain memory within the various different aspects of the peace movement. Take a quick look what CNVA was up to in the late 1970s as well. The call went out on February 16, 1977. Charlie King, Joanne McGloin, Joanne Sheehan, and Rick Gaumer, at the Community for Non-Violence in Voluntown, CT had evidence, from participating in the Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice that others were also singing and collecting songs that gave voice to people’s struggles. The group wanted to do what came naturally — bring these folks out of the woodwork and see what happened. Odetta should be mentioned as well. She may not have ever been to Connecticut or Tennessee but her songs sure have. She almost lived long enough to sing for Obama’s inauguration this year; but she died just last December not too long after saying how proud she was “that we now have a black man as president of the United States.” Giving voice to people’s struggles is what so many people around the United States hope the current President will do for them, but people like Odetta, Seeger, Baez and Carawan have always known it’s something we will always have to do for ourselves and for each other[...] -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust Recently, we heard a claim that Pete Seeger’s famous song “Bring Them Home” was inspired by the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA), specifically when a mob of students at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) confronted and threw rotten eggs at CNVA members Marge Swann, Bob Swann, and 23 others in 1966. Seeger had already been acquainted with the CNVA for at least 6 years, having participated in the Polaris Action in New London, Connecticut in the summer of 1960. Seeger first started playing the song “Bring Them Home” in 1966, not long after the CNVA-UNH incident. In the song, Seeger argues that supporting the troops means demanding that they be brought back to their own communities that need them, not encouraging them to go kill people halfway across the world. The lyrics contain a few lines that strongly resemble CNVA antiwar concepts (“Show those generals their fallacy… / They don't have the right weaponry… / For defense, you need common sense… / They don't have the right armaments”). But what actually happened at UNH in 1966, and why might it have inspired Pete Seeger to write this popular song?

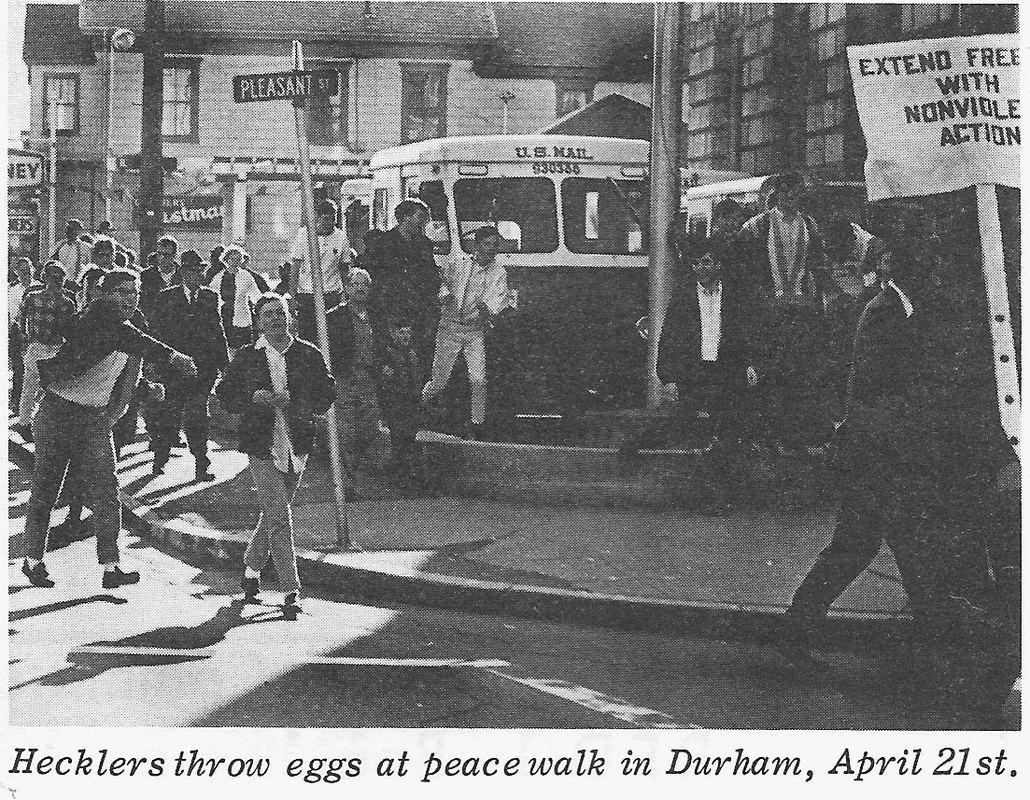

On April 21, 1966, twenty members of the New England and Boston chapters of the CNVA led by Marjorie Swann and Bob Swann attempted to hold a peace vigil for “the war dead of all participants in the Vietnam war” outside the Memorial Union Building at the University of New Hampshire. According to a 2012 post from UNH Today, when the CNVA members attempted to approach the building, they were met by a hostile mob of 2000 students. The CNVA members withstood eggs thrown at them for a while, but were eventually turned away by the mob. This incident evidently caused a great spiritual examination within the faculty, staff, and students of UNH. Starting almost immediately after the incident, members of the UNH community grappled with the meaning of what had happened. They were still talking about it when famous folk musician Pete Seeger came to the university to play a concert a couple weeks later. When Seeger arrived, he found that a petition had been circulating the school since the day after the incident, demanding the administration denounce the acts of the student-mob and to invite the CNVA back. By the end, the petition had over 700 names attached to it. After learning about what happened, Seeger penned his name to it, too. The UNH administration did invite the CNVA back for May 10, to which the activist group agreed. Before they arrived, however, the Durham Board of Selectmen banned all demonstrations by protesters who had previously been arrested for nontraffic-related incidents. This stipulation clearly targeted many CNVA members, several of whom had been arrested multiple times for nonviolent antiwar actions. In reaction to the arbitrary ban, several professors decided to lead the protest in the CNVA’s stead, marching ahead of about 120 Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) members and sympathizers, turning the demonstration into a protest both of the war in Vietnam and what the professors considered an unconstitutional restriction of freedom of speech. Meanwhile, 23 members of the New England and Boston CNVA chapters marched separately from the rest of the demonstrators, in defiance of the ban against them. In the official CNVA statement about the targeted restriction, the organization asserted: “To say that no person can participate in this parade who has been convicted by a court for other than traffic violations would ban from the streets of Durham many of mankind’s finest leaders, among them Jesus, the Apostle Paul, Socrates, Voltaire, Robert Browning, Thoreau, Dostoyevsky, Gandhi, Nehru, Martin Luther King—and a veritable army of others.” The statement then went on to mention other cities in both “democractic” and “communist” countries that have variously permitted CNVA demonstrations. “On the other hand,” the statement continued, “CNVA demonstrations have been prevented in some cities. Noteworthy is East Berlin, under the Ulbricht government; and Albany, Georgia, a notorious hard-core segregationist city. Just a few weeks ago it happened in Saigon, under the leadership of Premier Ky, who has avowed himself an admirer of Hitler… It is the policy of opponents of liberty everywhere to deny the right to demonstrate.” Several of the CNVA members would subsequently get arrested for violating the ban, but the rest ultimately made it to the Memorial Union Building and successfully held an hour-long silent vigil there. The arrested CNVA members were released after 11 days and all charges dropped for lack of evidence. Whether the CNVA-UNH egging incident really inspired Pete Seeger’s “Bring Them Home” or not, the story itself became a popular one told within many antiwar circles; the story has stuck in the minds of many older members of the antiwar movement to this day, as evidenced by the Seeger connection claim that was recently shared with us. The drama of the incident, which was the subject of many articles in The New Hampshire for weeks, did exactly what the CNVA wanted: to heighten the unjust contradictions in society and force people to reconsider the values that they had been conditioned to accept. “Success” for the antiwar activist may sometimes look like the opposite to the outsider, but the massive attention and targeted restrictions that the CNVA attracted all over, not least of all at the University of New Hampshire in 1966, demonstrated just how much of a threat to the status quo groups like the CNVA had come to be. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Gregonis, Peter. “PEACE WALKERS JAILED, BEATEN.” Direct Action for a Nonviolent World, 15 May 1966, pp. 2-3. Mayberry, David T. “Seven Pacifists To Be Arraigned For Parade Violations Tomorrow.” The New Hampshire, 12 May 1966, pp. 1-9. https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3040&context=tnh_archive Salstrom, Paul. “CNVA’ers ARRESTED.” Direct Action for a Nonviolent World, 15 May 1966, pp. 1-2. Swann, Marj. Prospectus For a History of New England CNVA (unpublished), pp. 124-143. Vreeland, Peg. “Pacifists Invited Back to UNH.” The New Hampshire, 28 Apr. 1966, pp. 1–8. https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3038&context=tnh_archive Woodward, Mylinda. “The Way We Were: In 1966 a Mob Tried to Stop a Peaceful Protest.” UNH Today, 12 April 2012 (accessed 16 June 2021). https://www.unh.edu/unhtoday/2012/04/way-we-were-1966-mob-tried-stop-peaceful-protest June is LGBTQ+ Pride Month, commemorating the 1969 Stonewall Riots that are largely credited as the beginning of the “gay pride” movement. Every June, queer organizations and individuals recount the story of Stonewall, or at least evoke the powerful images of Black and Brown transwomen and gangs of young gay runaways finally refusing to accept the constant and targeted harassment they had previously endured from both the police and the public. But our annual observance of Pride today was not an inevitability; Stonewall was not the first “gay” riot, and it could have been buried under the homophobic hegemony like other ones that preceded it. Instead, several queer groups already operating in New York City and around the United States made Stonewall the catalyst to join together, to articulate a new vision of queer liberation, and to act to manifest it.

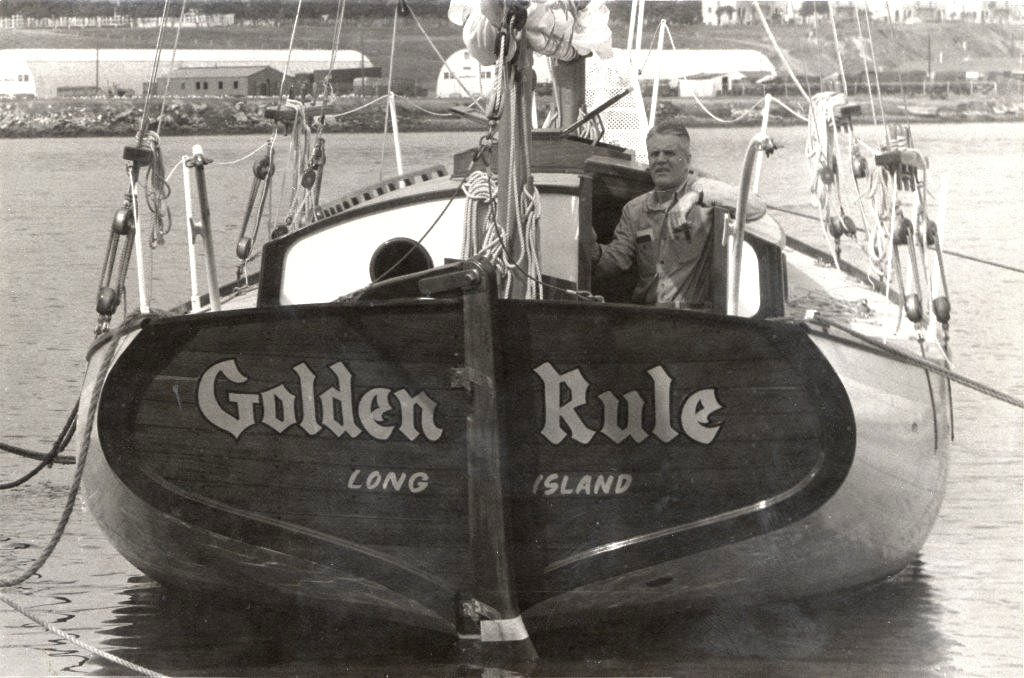

By so many measures, 1969 was a watershed year: no less so in queer circles across the United States. Organizations of “homophiles” had existed for some years before, especially in the major cities, but were largely led by an older generation. In 1962, groups like the Mattachine Society, the Daughters of Bilitis, and the Janus Society formed the East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO) and, later, the larger Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) to coordinate their political efforts. One such effort was the Annual Reminder: a silent picket held on July 4, 1965-1969 outside Liberty Hall, Philadelphia to remind the country that queer people were still denied the most basic rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” At the insistence of one of the organizers, Frank Kemeny, there would be a strict, gendered, formal dress code and any behavior that might be “shocking” to the public was forbidden. But by 1969, a new generation of queer people were less interested in silent pickets and trying to prove their respectability, but was instead looking to the dramatic actions of the antiwar, feminist, and civil rights movements — the “counterculture.” Even before the Stonewall Riots began, this mostly younger generation of radicals started forming small, independent queer groups like the Mattachine Action Group with the intention to “spark public consciousness.” Then, in the early hours of June 28, 1969, somebody fought back during a police-raid of the popular Manhattan gay bar Stonewall Inn and riots mostly led by transwomen broke out for the next several days. Those small groups of queer radicals started organizing, producing leaflets and flyers exposing the bar’s Mafia owners as well as the corrupt deal they had with the police. Then they began organizing public meetings and merged to eventually form new groups like the militant New Left-oriented Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and eventually the more moderate single-issue Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). These new groups were much more diverse than many previous groups, with many more Asians, Latinx, and Blacks as well as more trans people. Over the next several months, these groups would develop “zaps” as a direct action tactic to force important figures to publicly address the issue of queer oppression. After the riots had ended, some ERCHO members who had been radicalized by Stonewall, including organizer Craig Rodwell, went down to Philadelphia to participate in what would be the final Annual Reminder. There, a lesbian couple purposely defied the order for “lawful, orderly, dignified” behavior and broke ranks to hold hands. When Frank Kemeny tried to separate them, Rodwell became furious; and when Kemeny was later speaking to the press, Rodwell interrupted to denounce the “gay” leadership’s meek pleas for acceptance, pointing to Stonewall as evidence. The Annual Reminder was over, but in the next few months, Craig would join with others to convince ERCHO to endorse the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee (CSLDC, named for the street where the Stonewall Inn was), which was to organize a commemorative celebration of the Stonewall Riots. Announcements were made to the various ERCHO groups, as well as sister groups across the country encouraging them to organize their own festivities in tandem. It was decided that the celebration would not have any commercial ties, but that it would be permitted and well-organized. The CSLDC began monthly meetings in January 1970, but moved to weekly meetings in April. They raised the money, appointed marshals, planned a route for a “march for freedom” through midtown Manhattan up to Central Park, and organized events at the march’s end. They produced and distributed advertisements, bulletins, and press releases to every publication that would print them. A sister celebration was announced in Los Angeles. And they got the permits, even if the last of them arrived just hours before the opening march was to begin. On June 28, 1970, exactly one year after the beginning of the Stonewall Riots, the first Christopher Street Liberation Day was celebrated. A delightful, colorful procession of fabulous drag queens and transwomen, members of GAA and GLF holding banners, and gaggles of gay men and women marched up the center of New York City unharassed. The New York Times reported on its front page the next day that the march extended about 15 blocks. Thousands took part; for some, this was the first time that they had ever expressed their queer identity publicly in daylight. The cathartic, catalytic rage from one year prior had been forged into comradery, hope, and joy. And the changes in queer communities stemming from the 1960s counterculture that inspired the formation of new action groups and spurred the Stonewall Riots was now undeniable. Now, through the work of all those queer people radicalized one year before, more people than ever could feel it, too. Over the next few years, the GLF would collapse and more white and trans-exclusionary elements would come to dominate the Christopher Street Liberation Day celebrations (which would later be renamed Gay Pride), leading prominent trans members of the NYC queer community like Marsha P. Johnson to publicly break with the group in 1973. And although Pride celebrations are now generally as inclusive as possible, racism and trans-exclusionary prejudice are still major problems in many queer communities today. Despite these obstacles, as well as the devastation of the AIDS epidemic years later, the movement that started 52 years ago has accomplished an incredible amount in a relatively short period. And much of what has been accomplished owes a great debt to those small initial groups of young queer radicals who defied the prescribed wisdom and boldly asserted their right not just to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” not just to acceptance, but to PRIDE. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Baumann, Jason, ed. The Stonewall Reader. Penguin Books, 2019. Clendinen, Dudley and Adam Nagourney. Out for Good: The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America. Simon & Schuster, 2001. Duberman, Martin B. Stonewall: The Definitive Story of the LGBTQ Rights Uprising That Changed America. Plume, 2019. About 63 years ago, the small sailing vessel the Golden Rule became the first civilian ship to ever attempt to disrupt a nuclear weapons test. From July 1946 to August 1958, the United States detonated 23 of its largest nuclear weapons at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, directly killing at least one person through radioactive fallout, irradiating the ecology of the atoll to fatal levels, and directly causing the world’s first nuclear diaspora (read our post on it here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/1959579410859051). By 1958, calls for a ban on atmospheric and other nuclear weapons testing had been ringing out for years worldwide, but no one had yet attempted to actually stop the largest of these tests with direct action. Part of the challenge was that Bikini Atoll and the rest of the US Pacific Proving Grounds were in the middle of the largest ocean on Earth. But by the late 1950s, a new generation of activist groups, including the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) began experimenting with novel forms of civil disobedience to protest unjust government policies. On June 4, 1958, the four-person crew of the CNVA-sponsored ketch the Golden Rule attempted such an experiment: by risking their lives to sail into the middle of the Pacific Ocean, into the middle of an active nuclear weapons testing site, to try to halt their own government’s belligerently provocative testing of these weapons of mass destruction.

The planned Pacific voyage was not the first nuclear protest the CNVA had organized. On August 6, 1957, the twelfth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, about 35 people gathered outside of the gates of the Nevada Proving Grounds and held a group prayer, a conscience vigil, and an act of civil disobedience by crossing the line into the restricted zone. Among those arrested in the action was Marj Swann, cofounder of the Voluntown Peace Trust, as well as Albert Bigelow, a former lieutenant commander in the US Navy. The story of Swann’s involvement, and the sexist chastising she experienced from the judge of her case, inspired an article in the popular women’s magazine Redbook titled “You Are a Bad Mother.” Bigelow had resigned from his position in the US Navy soon after learning of the US atomic bombing of Hiroshima, just one month from eligibility for his pension, and in the years after the Second World War, Bigelow joined the Quakers and became a pacifist. Within the next few months, Marj Swann, Albert Bigelow, and others came to form the Committee for Nonviolent Action, which over the next several years became known for several of their dramatic actions in resistance to nuclear arms. When the announcement for another round of nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll came in September, just a month after the action in Nevada, the newly formed Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) and National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), as well as the Religious Society of Friends began a protest campaign to halt them. Albert Bigelow joined the effort, ultimately delivering a petition of 17,500 names against nuclear weapons testing to the office of President Eisenhower. Because no one actually wanted a nuclear war, and President Eisenhower himself had called for “a giant step toward peace,” the petition argued to cancel all planned tests, to allocate those funds to the Special United Nations Fund for Economic Development (SUNFED), and to challenge the Soviet Union to do the same. But when the petition disappointingly received no response from the White House, the CNVA began planning a new action the government could not ignore: to sail a ketch into the test site and disrupt it themselves. After some hesitation, due to his nautical experience, Albert Bigelow was convinced to captain the little boat. They named the Golden Rule for the principle they requested their government apply to its nuclear arms program and spent the first few months of 1958 in preparation for the voyage. Around the same time across the Atlantic, the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament held their first public meeting in London. There, artist Gerald Holtom presented a circular symbol with a vertical line through the center and two diagonal lines falling at 45° from the center, meant to be a stylized combination of the semaphore signs for N and D: nuclear disarmament. The symbol originally debuted to the world at the first Aldermaston March for nuclear disarmament on Easter 1958. The American antiwar and civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin participated in the march and, when he returned home, shared the new symbol with his cohorts in the various US antiwar and racial justice groups. At some point, it was introduced to the crew of the Golden Rule, who eventually got a flag with the ND symbol to fly from their mast, spreading the symbol even further. In March 1958, Skipper Albert Bigelow, First-Mate William R. Huntington, and Crewmembers George Willoughby and Orion Sherwood set sail from San Pedro, CA to Honolulu. As the CNVA informed President Eisenhower of their plan beforehand, the US Atomic Energy Commission issued an injunction against all Americans sailing into the testing zone while the Golden Rule was en route to Honolulu. The little ketch successfully sailed across the open ocean, but by the time they arrived in Hawai’i, the US Coast Guard was waiting for them. On May 1, the Golden Rule set sail from Honolulu towards the Marshall Islands, but was stopped just five nautical miles from shore. The US Coast Guard arrested the four men and tugged the boat back to port, but released them quietly, hoping not to add to the significant publicity the endeavor had already generated. Just over a month later, on June 4, the crew tried once more. They were again stopped and arrested, this time receiving a 60-day jail sentence. After their stint in jail, the crew returned to the mainland and continued in the peace and civil rights movements for some years. And although the crew of the Golden Rule was unable to complete the action that they had set out to accomplish, they inspired another crew to do it in their stead. Within a month of the Golden Rule crew’s sentencing, the Phoenix of Hiroshima successfully sailed into the testing zone near the Marshall Islands. The combined public exposure of the Golden Rule’s dramatic saga and the successful, surprise conclusion of the project by the Phoenix of Hiroshima inspired a new wave of global calls to limit nuclear weapons testing. Five years later, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, banning all atmospheric, underwater, and outer space tests of nuclear weapons. But the Golden Rule and the Phoenix of Hiroshima did not just try to sail into restricted waters and kickstart the antinuclear movement: they invented a whole new method of protest. Within a couple years of the voyage, many others would copy and expound upon the idea of protest sea vessels such that by 1960, peace activist Scott Herrick would be sailing his sloop Satyagraha up and down the Thames River in Connecticut to protest the construction of the world’s first nuclear-armed submarines at General Dynamics - Electric Boat near the mouth of the river: the words “End the Arms Race” in big letters on one of its sails and the ND “peace” symbol on another. In the late 1960s, activists in Vancouver, British Columbia organizing against underground nuclear weapons testing at Amchitka, Alaska decided to try their own version of the 1958 project. Starting in 1971, the group that would become known as Greenpeace began to attempt disruptions to the tests using civilian sea vessels, successfully forcing the United States government to cancel the rest of the tests after the government received immense criticism from the first. Today, Greenpeace is far from the only organization using protest vessels to take action and spread a message. But in 2015, members of the organization Veterans for Peace completed the restoration of a particularly special protest ship: the original Golden Rule. Today, Veterans for Peace operates the vessel to “advance… opposition to nuclear weapons and war, and to do so in a dramatic fashion.” -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources “1958–1961: Nuclear Protests.” Phoenix of Hiroshima Project. (Accessed 2 June 2021). https://phoenixofhiroshima.wordpress.com/our-history/pleasure-yacht/ Bigelow, Albert. The Voyage of the Golden Rule: An Experiment with Truth. Doubleday, 1959. “Friends Journal 1958 coverage of the Golden Rule.” Friends Journal. 31 July 2013 (accessed 2 June 2021). https://www.friendsjournal.org/golden-rule-1958/ “The Golden Rule and Phoenix voyages in protest of U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands, 1958.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. (Accessed 2 June 2021). https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/golden-rule-and-phoenix-voyages-protest-us-nuclear-testing-marshall-islands-1958 “History.” VFP Golden Rule Project. (Accessed 2 June 2021). https://www.vfpgoldenruleproject.org/history/ Little, Jane Braxton. “Restored Anti-Nuke Sailboat Launches Again on a Peace Mission.” National Geographic. 19 June 2015 (accessed 2 June 2021). https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/150619-golden-rule-ketch-restoration-nuclear-weapons?loggedin=true Miles, Barry. Peace: 50 Years of Protest. Essential Works Limited, 2008. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed