|

For this week’s Peace of History:

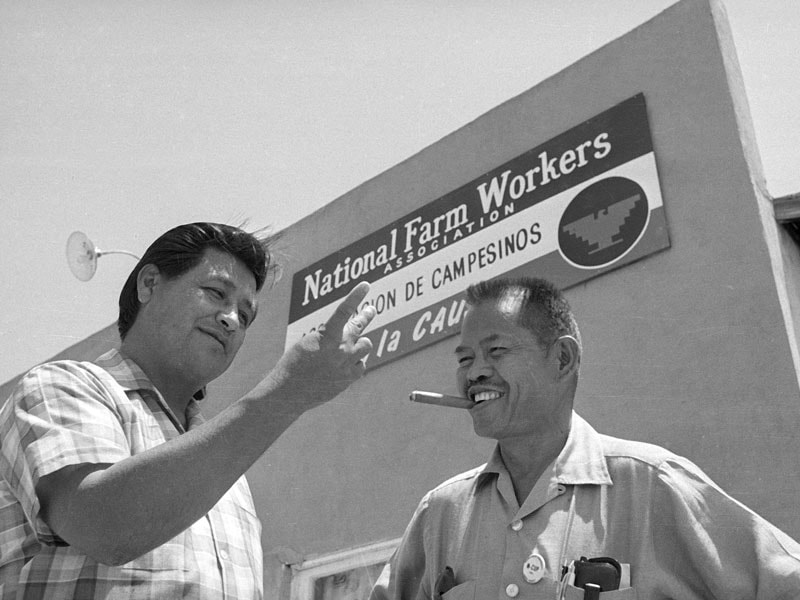

Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of the successful end of the 5-year Delano Grape Strike, which saw the formation of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW) and the rise of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta as legendary figures in the labor movement. And yet much has been forgotten, written out, or otherwise misunderstood about why the strike started in the first place, who was involved, how it succeeded, and what followed. Too often, key pieces of contextual history are excluded from the telling of a story. A more complete history of the founding of the UFW must include the story of Larry Itliong’s leadership, the initial unity of the Filipino-American manong generation and Mexican-American farm workers, and the dangers of placing too much power in the hands of a single person. To understand the Delano Grape Strike, we must trace back two separate lines, how they came together, and why they frayed apart. Following the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), the United States aggressively colonized the Philippines on multiple fronts. As a result of colonization, from 1917 to 1934, the tens of thousands of Filipino immigrants to the United States in the early 20th century did not face the heavy immigration restrictions that other Asians received, and many Filipino immigrants did not initially feel like such outsiders. Upon immigrating, however, Filipinos often suffered racist violence, prejudice, and segregation. It was not unknown for bosses to physically whip and beat Filipino workers, call grown men “boys,” and perform other acts of dehumanization. Moreover, in 1934, Congress changed immigration laws to change the status of all Filipino-American citizens to “alien,” and to restrict new Filipino immigration similarly to other Asians. Furthermore, anti-miscegenation laws prevented “Whites” (including most Hispanics) from marrying “Blacks,” “Asians,” and after 1930, “Filipinos.” With a gender disparity of 14 men to 1 woman in Filipino immigration in the early 20th century, this lost generation of mostly unmarried men became known as the manong (“older brother”) generation to later Filipino immigrants. The manong formed alternative communities and economies based both on their Ilocano Filipino heritage and on the new itinerant lifestyles many had adopted in the United States. While some Filipinos came to participate in American universities, the vast majority were young men seeking migrant manual labor. These mostly male communities dotted along the west coast and relied as much on the migrant Filipino agricultural workers as the workers did on these communities. Through years of traveling, working, eating, and sleeping side-by-side together, the manong developed a strong group identity and mutual trust with each other. Thus, they also started organizing as workers in the face of racist exploitation early on. When Larry Itliong immigrated to the United States in 1929 at the age of 15, Itliong found manong already starting to organize, and he quickly got involved. Over the years, Itliong helped to organize cannery and agricultural workers unions from Alaska’s dangerous fisheries in the north to California’s massive plantations in the south. Larry Itliong became known among the other manong for his charisma, militance, and skill in organizing. The 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s saw frequent, sometimes violent resistance from Filipino laborers in the United States, which was often successful at winning higher wages and other short-term concessions, but never resulted in written contracts with codified improvements. At first, the Delano Grape Strike in 1965 seemed to follow the pattern. The predominantly Filipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) led by Larry Itliong had won a strike months earlier in May against Coachella Valley grape growers ended with the typical results: no contract. Moving north to Delano in September, Filipino workers asked the AWOC to help organize a strike to win the same wages as in Coachella Valley. The strike began on September 8. Mexican-American workers, however, had also migrated into the area, and could easily provide the scab labor for the grape growers -- another pattern which had previously often led to Filipino workers physically confronting and fighting Mexican-American workers. But this was 1965: Dr. King’s message of interracial harmony, equal justice, and nonviolent methods were world-famous. Things were different now. And besides, by this time, most of the manongs were in their 50s and 60s, their bodies weathered by decades of manual labor -- Larry Itliong himself had years ago lost three fingers in a fishing accident. Itliong evaluated the situation carefully. Around the same time, Mexican-American workers on the west coast were starting to organize. The bracero federal workers program had ended in 1964, opening up more opportunities for Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to organize primarily Mexican-Americans working in agriculture. Chavez dreamed of leading a Chicano movement, with labor a key component. Huerta had already demonstrated her skill in community organizing with her work improving conditions in barrios, and looked to the farm workers as the next step. The two formed the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) in 1962, grew the membership rapidly, and in April 1965, helped to organize a short, successful strike for rose grafters. The NFWA’s reputation was growing steadily, but Chavez himself felt that they would not be ready for a large-scale strike for at least another three years. And yet, when Larry Itliong approached Chavez personally to join the strike, Chavez felt backed into a corner. The issue was put to a vote with the NFWA, and on September 16, Mexican Independence Day, an overwhelming majority of the more than twelve hundred of his union members voted in support of the Filipino workers. For years after, Mexican and manong workers alike picketed together, ate or went hungry together, and slept on the same dusty cold floors together. With the NFWA’s superior numbers, Chavez quickly took over organization of the strike, sending representatives to the Longshoremen to convince them not to pack grapes. Soon, the United Automobile Workers pledged financial support to the strikers. Inspired by the boycott tactic popular in the Civil Rights Movement, Chavez met with SNCC to learn their methods and foster an alliance. They started a national boycott of California grapes, with Dolores Huerta coordinating a campaign that sent hundreds of strikers across the country to share their stories. Chavez eventually led a 300-mile march from Delano to Sacramento to draw attention to the farm workers’ plight. The message was simple and clear: tens of thousands of strikers are making enormous sacrifices to secure labor justice and dignity as workers -- but average Americans can help by making the small sacrifice of abstaining from grapes. Unlike many of the boycotts of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, which were usually focused on local or regional businesses, the farm workers’ boycott campaign brought distant struggles for justice into countless grocery stores and suburban homes. This strategy proved to be particularly effective, and laid the groundwork for the success of future national boycotts like the Lettuce Boycott of 1970-1971 and the Gallo Wine Boycott of 1973-1978. About a year into the strike, the AWOC and the much larger NFWA merged to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, later known as the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), with Chavez as General Director and Itliong as Assistant Director. It was well-known, however, that Chavez organized around himself as a “one man union” with a few close, ambitious, like-minded confidantes like Huerta to carry the rest of the responsibilities. Itliong and other Filipino labor leaders found themselves a “minority within a minority,” filling largely symbolic roles in a union that increasingly seemed to forget about the very workers who started the strike in the first place. After five long years, in July 1970, the UFW won the strike over the Delano grape growers, and a contract for the agricultural workers specifying codified rules to improve conditions in the fields -- a first for the manong. But provisions negotiated by Chavez and Huerta also implemented hiring systems that drastically disrupted manong communities, many of whom still had no families or savings for support. The concerns of these aging Filipino men were increasingly ignored as they became a smaller and smaller minority in an organization they helped found. Chavez appointed Itliong the National Boycott Coordinator of the UFW in 1970, but Itliong increasingly felt uncomfortable with his own unelected position and how Chavez ran the union. In 1971, Itliong resigned from the UFW, citing the lack of concern for the manong workers and Chavez’ particular leadership style as his reasons. A key figure in the Asian American Movement, Larry Itliong continued to organize and advocate for his fellow manong workers until his death in 1977. Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez went on to become powerful figures in the labor and Chicano movements, and undoubtedly effected positive changes for countless workers. Utilitarianism posits that whatever effects the greatest good for the greatest number of people is the most ethical choice -- under such an analysis, the UFW’s victory in the Delano Grape Strike was an overwhelming success. But at the same time, many manong concerns were neglected, and some ended up worse off than before. As we build up our own groups and form coalitions, let us not repeat the mistake of the UFW. Let us remember the minority within the minority. Sources: “The 1965-1970 Delano Grape Strike and Boycott” https://ufw.org/1965-1970-delano-grape-strike-boycott/ “‘A Minority Within a Minority’: Filipinos in the United Farmworkers Movement” https://prizedwriting.ucdavis.edu/sites/prizedwriting.ucdavis.edu/files/sitewide/Barbadillo_vol28.pdf “COACHELLA VALLEY: Filipinos’ 1965 strike set stage for farm labor cause” https://www.pe.com/2005/09/03/coachella-valley-filipinos-1965-strike-set-stage-for-farm-labor-cause/ The Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the UFW https://www.pbs.org/video/kvie-viewfinder-delano-manongs/ Dunne, John Gregory. Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike. 1971 https://books.google.com/books?id=GQ1JkSnNmLQC&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false Jiobu, Robert M. Ethnicity and Assimilation: Blacks, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Japanese, Mexicans, Vietnamese, and Whites. 1988 https://books.google.com/books?id=VJa9SDpTfzEC&pg=PA49#v=onepage&q&f=false “The Forgotten Filipino-Americans Who Led the ’65 Delano Grape Strike” https://www.kqed.org/news/10666155/50-years-later-the-forgotten-origins-of-the-historic-delano-grape-strike “Forgotten Hero of Labor Fight; His Son’s Lonely Quest” https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/19/us/larry-itliong-forgotten-filipino-labor-leader.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 For this week’s Peace of History:

We mourn the deaths of the Rev. C.T. Vivian and Representative John Lewis, who both passed away last week on Friday, July 17, 2020. Their experiences in the Civil Rights Movement, in different but intersecting ways, feel especially pertinent for us to examine in our present historic moment. As the Black Lives Matter movement grows and enters a new phase, and many are wondering what comes next -- let us honor the memories of these lifelong titans in the struggle for justice by examining their early experiences with nonviolent action and their roles in the campaign that shaped a generation of protests: the Nashville Lunch Counter Sit-Ins. C.T. Vivian’s first experience with nonviolent action happened earlier than many of his peers. In Peoria, IL, 1947, Vivian became involved in his first sit-in campaign to desegregate local lunch counters and restaurants when he met Ben Alexander, a member of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and a local minister. They led a successful campaign using the methods developed by CORE: asserting a nonthreatening but absolutely unavoidable presence to confront consciences directly. Over a decade later, upon being called to ministry, Vivian went to Nashville to study at the American Baptist Theological Seminary. There, in 1959, he met James Lawson, who was teaching Gandhi’s principles and strategies that he had learned in India. Lawson was a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), the southern director of CORE, and was himself enrolled at the Divinity School at Vanderbilt University -- so he started his nonviolent trainings with other ministers and Black students who attended several colleges in Nashville. Students drawn to the workshops included Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel, and none other than John Lewis. Many were skeptical going in, but later became some of the most disciplined practitioners and outspoken proponents. Vivian, although having experienced a nonviolent action campaign in practice before, still did the workshops to learn the strategic principles and greater social philosophy of nonviolence, and became a skilled trainer himself. Lawson started leading these training sessions sporadically out of the basement of his church in 1958, as he got to know C.T. Vivian and other Black ministers and students in Nashville. By the Fall of 1959, more students and young people were becoming interested, momentum had picked up, and Lawson held trainings every Tuesday night for at least the 5 months before the Nashville Sit-In campaign would commence. John Lewis, like so many others of his peers, was enraptured. Also in school for the ministry at American Baptist Theological Seminary, Lewis heard Lawson discussing nonviolence and felt that “it was something I’d been searching for my whole life.” Lewis, like Vivian, quickly became immersed in the nascent movement, becoming a founding member of the Nashville Student Movement in October 1959. Four months later, on February 13, 1960, in-part inspired by the start of the Greensboro Sit-Ins less than two weeks prior, the students initiated their first sit-ins in downtown Nashville. No one could have known that the success of the Nashville Sit-In campaign would have such immense and lasting consequences. One effect was that the student-leaders emerging from the campaign quickly formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and some members trained by James Lawson went to train more people in other cities across the South -- seeding the principles, strategies, and practices of nonviolent direct action across the region. Others, like John Lewis and C.T. Vivian, built upon the practice of nonviolent action. On May 4, 1961, Lewis joined 6 other African-Americans and six white allies from the North when CORE revived an old FOR project: the integrated Freedom Rides through the South. C.T. Vivian participated in some of the last Freedom Rides that summer, despite the continuing violence against Riders. Lewis and Vivian both suffered nearly deadly attacks on multiple occasions, but when the rest of CORE decided to shift priorities elsewhere, in part to avoid further violence, Lewis, Vivian, and Diane Nash had SNCC take over the project, successfully completing the last rides in August of that year. As we look at the chain of events that would lead to John Lewis addressing over 200,000 people alongside Dr. King at the 1963 March on Washington, to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, to C.T. Vivian’s founding of Upward Bound in 1965, Black Action Strategies and Information Center (BASICS) in 1977, and Center for Democratic Renewal with Anne Braden in 1979, and beyond -- we have the privilege of knowing how the stories of C.T. Vivian and John Lewis end. Those foundational experiences, especially those early training workshops and action campaigns, almost read like convenient origin stories for legendary persons like Vivian and Lewis. But it is essential for us to remember that the early successes of the Civil Rights Movement did not come from nowhere, but instead emerged from months of educating, training, and coordinating. James Lawson tilled the soil and planted the seeds -- but he could not have known that his students like C.T. Vivian and John Lewis would carry the fruits of his labors so far. Now, it is our turn. CALL TO ACTION: Voluntown Peace Trust is planning to run a ~2 hour Intro to Direct Action Workshop next week, between Monday and Thursday. This 2-hour Zoom workshop explores one of the most foundational campaigns in the Civil Rights Movement, which took place in 1960 and still has much to teach us today. Both John Lewis and C.T. Vivien, who died this past week, were involved. The 25-minute documentary “Nashville: We Were Warriors” from “A Force More Powerful” shows the power of nonviolent action training and how strategic planning can create a successful campaign, while introducing us to the students and ministers who were at the core of this campaign and who went on to be key strategists, organizers, and trainers in the Civil Rights Movement. Rev. James Lawson’s workshops in Nashville were the training grounds. This workshop’s agenda includes exercises to help us better understand the lessons they learned about strategic nonviolent actions. Sources: “C.T. Vivian” http://www.ctovma.org/ctvivian.php “C.T. Vivian, civil rights hero and intellectual, dead at 95” https://www.ajc.com/news/ct-vivian-civil-rights-hero-and-intellectual-dead-at-95/2GOB7SU7MZDHJADH63LIKYHK6M/ “C.T. Vivian, Martin Luther King’s Field General, Dies at 95” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/17/us/ct-vivian-dead.html “Jim Lawson Conducts Nonviolence Workshops in Nashville” https://snccdigital.org/events/jim-lawson-conducts-nonviolent-workshops-in-nashville/ “John Lewis” https://snccdigital.org/people/john-lewis/ “John Lewis recounts Freedom Rides, 50 years later” https://www.ajc.com/news/local/john-lewis-recounts-freedom-rides-years-later/mz9l7sgB4TYxhWqbAeS51O/ “John Lewis, Towering Figure of Civil Rights Era, Dies at 80” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/17/us/john-lewis-dead.html “Oral History Interview: Reverend C.T. Vivian” https://www.crmvet.org/nars/vivian2.htm For this week’s Peace of History:

We celebrate the birth of prolific protest troubadour Woody Guthrie. Born July 14, 1912 in Okemah, Oklahoma, Guthrie’s restless nature carried him across the United States, eventually becoming one of the country’s most beloved folk singers -- both in his time and today. Like many larger-than-life historical figures, however, Woody Guthrie’s legacy has been so severely sanitized that the man and meaning behind his songs are all but forgotten -- in the case of his most famous song, “This Land Is Your Land,” even much of his own lyrics are often omitted. So let us take a look at the man himself, how he embodied his radical beliefs, and how he’s inspired generations of protest music. As a young man, he traveled west to California as one of thousands of “Okies” fleeing the Dust Bowl and seeking agricultural work. Guthrie, always having been a musician, found work as a broadcast radio performer playing commercialized “hillbilly” and folk music. Some of his success came from the growing popularity of traditional folk songs and the romanticisation of the working class -- Guthrie’s background as an Okie and a troubadour lent a great deal of rural working class authenticity, despite his family’s middle-class background. Guthrie took advantage of this national fascination with “hillbillies” and other “traditional” rural folks to sing about the plight of fellow migrant workers and other working class issues -- giving voice to the voiceless. Many of these songs would later be collected and recorded for his first album Dust Bowl Ballads. During this time, newscaster Ed Robbin introduced Guthrie to communist circles and became something of a political mentor to Guthrie. Unlike certain anarchist groups like the IWW, which had published their “Little Red Songbook” in 1909, many communist and socialist groups had been slow to adopt music as a tool for protest and forming unity. That attitude shifted shortly before Woody Guthrie entered the scene. Although never a card-carrying member of the Communist Party, the ideology fit perfectly with Guthrie’s own personal politics and experiences as a migrant worker. After learning more, Guthrie openly supported communism, played benefit shows at leftist events, and even wrote a regular column in the communist newspaper People’s World, in which he gave social commentary with an exaggerated hillbilly dialect. Guthrie and his communist friends realized that, like with commercial folk music, Guthrie’s Okie reputation could lend a kind of homegrown American authenticity to the communist movement, as well. At some point, he made enough money to send for his wife and children to join him in California, but after the signing of the non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and Germany in 1939, Guthrie and Robbin were both fired for fear that they would spread Soviet propaganda. Guthrie moved his family back to Texas, but then himself moved up to New York City where he got in with the folk music scene there, achieving even more success on the radio and busking on the side. In 1940, Guthrie used his growing clout in the radio world to secure a regular CBS spot for his friend Huddie Ledbetter, a.k.a. “Lead Belly,” which helped bring Lead Belly back into popularity. Around this time, Woody Guthrie also met Pete Seeger at a benefit concert for farm workers organized by John Steinbeck, and the two became lifelong friends. Guthrie joined Seeger’s newly formed folk-protest group the Almanac Singers, first writing “peace” songs, and then moving on to anti-fascist songs after the surprise Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1939. After his divorce from his first wife, anti-fascism took on new meaning to Guthrie when he began working extensively with his second mother-in-law, Yiddish poet Aliza Greenblatt. He would come to be strongly influenced by Jewish traditional folk music, and he wrote many songs about Hanukkah and Jewish history in the 1940s. Despite some of his personal flaws, Guthrie’s unwavering commitment to justice and the oppressed classes suffuses his immense repertoire. He never really stopped writing protest songs, even as his mental and physical health deteriorated -- in 1950, two years before he was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, Guthrie wrote “Old Man Trump” a brief, unpublished ditty about his racist landlord, Fred Trump. Privately, he wrote about racist housing discrimination following WWII, and how landlords like Fred Trump gleefully enforced and profited from such policy. In one notebook, he imagined himself transforming the whites-only complex where he lived, all around him “a face of every bright color laffing and joshing in these old darkly weeperish empty shadowed windows,” and then calling out to a young African-American woman: “I welcome you here to live. I welcome you and your man both here to Beach Haven to love in any ways you please and to have some kind of a decent place to get pregnant in and to have your kids raised up in. I’m yelling out my own welcome to you.” Perhaps due to his experiences as a migrant worker, Guthrie consistently saw kinship in other peoples’ struggles for justice and liberation. His unapologetically radical politics inspired countless other musicians to use their songs in protest -- most notably Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, John Mellencamp, Billy Bragg, Tom Paxton, and so many more. People's Music Network for Songs of Freedom and Struggle, which began here at VPT, continues that tradition of protest music. Indeed, Guthrie literally wrote the words “this machine kills fascists” prominently on his guitar -- to Woody Guthrie, music was more than mere self-expression. Music could do things to people: open hearts, change minds, deepen understanding. And due to his Okie-folksy reputation and the cultural trends of the time, Guthrie leveraged his influence to support certain causes in ways even many other popular musicians could not. Woody Guthrie showed us in his brief time on Earth the enduring power of music to inspire and change people, even whole societies -- and how it can start with just one person. Let us leave you this week with this, the commonly-omitted verses of Guthrie’s most famous song, “This Land is Your Land”: As I went walking I saw a sign there, And on the sign it said "No Trespassing." But on the other side it didn't say nothing. That side was made for you and me. In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people, By the relief office I seen my people; As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking Is this land made for you and me? Nobody living can ever stop me, As I go walking that freedom highway; Nobody living can ever make me turn back This land was made for you and me. Sources: Cray, Ed. Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004. Galyean, Crystal. “This Machine kills Fascists.” https://ushistoryscene.com/article/woody-guthrie/ Guthrie, Woody. “Ear Players.” Common Ground, Spring 1942, pp. 32-43. “Happy Joyous Hanukkah & Wonder Wheel.” https://www.woodyguthrie.org/merchandise/klezmatics.htm Kaufman, Will. “Woody Guthrie, ‘Old Man Trump’ and a real estate empire’s racist foundations.” https://theconversation.com/woody-guthrie-old-man-trump-and-a-real-estate-empires-racist-foundations-53026 “This Land Is Your Land.” https://www.woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/This_Land.htm For this week’s Peace of History:

We celebrate the birth of activist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau. Born July 12, 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, Thoreau’s influence on American culture has persisted well beyond his time. His observations contributed significantly to the field of natural history, and many of his observations anticipated future discoveries in ecology. The transcendentalist philosophy which he followed believed in the inherent goodness of individuals, a deep suspicion of the corrupting influence of society and institutions, and the value of self-reliance and personal freedoms -- it is not hard to find reflections of those beliefs in various forms across contemporary American culture today. His account of his Walden years still continues to inspire experiments in off-grid homesteading and alternative lifestyles. But for the pacifist movement, it is his tax resistance and the development of his concept “civil disobedience” that holds a special relevance. On July 4, 1845, Thoreau began his famous experiment at Walden Pond on property owned by the unofficial leader of the transcendental movement, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In the transcendentalist tradition, Thoreau’s goal was to live simply and self-sufficiently in nature in order to develop a more objective perspective of society. He used this time to observe, think, and write about the relationships between individuals, between individuals and society, and between people and nature. A staunch lifelong abolitionist, in 1840, Thoreau had started refusing to pay taxes in protest of slavery. About one year into his stay at Walden Pond, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector, who demanded the unpaid poll taxes of the last six years. Citing slavery and the recently begun Mexican-American War, which many abolitionists considered a Southern invasion into sovereign lands to expand slavery, Thoreau refused to pay and spent a night in jail. Against his wishes, a family member paid his back taxes and he was released the next day. That encounter with the State affected him greatly; two years after the incident, Thoreau delivered lectures in Concord, MA that would become the basis of his famous essay “Resistance to Civil Government,” also known as “Civil Disobedience.” In it, he wrote: “A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight… If a thousand men were not to pay their tax-bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution, if any such is possible.” He frames the individual’s moral relationship with the State in binary terms: either you support the State through paying taxes, thus literally financially supporting the violence and brutality of the State; or you withhold your taxes from the State and sleep well knowing that no one has been hurt or killed with your tax dollars. It is also worth noting that despite the transcendentalist tendency to prioritize the importance of the individual, Thoreau nevertheless clearly states that collective action, even amongst a minority, is the only method for nonviolent revolution. Even more, he seems to say that a collective refusal of the State is the definition of a peaceful revolution. Much of the rest of the essay concerns the individual’s spiritual and physical struggle with the State, but here, Thoreau is explicit about the necessity for individuals to take action collectively in order to establish a truly just government. Henry David Thoreau was not strictly speaking a pacifist. Indeed, after John Brown’s violent and ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry and his subsequent execution, Thoreau is credited for being the first person to publicly support John Brown’s actions, even as other abolitionists tried to distance themselves from Brown. But his concepts of collective nonviolent action as a viable means of revolution have reverberated and inspired pacifists across the world: to Russia, where Leo Tolstoy developed the ideas even further using anarchist philosophy and Christian theology; to India, where Gandhi successfully led the independence movement from the British Empire by means in-part inspired by “Civil Disobedience”; back to the United States, where “Civil Disobedience” inspired the modern war tax resistance movement promoted by the Peacemakers and CNVA; to the South, where the Civil Rights Movement famously and spectacularly employed the strategy to end segregation and voting disenfranchisement. Now, individuals are coming together to pull down statues, to form police-free neighborhoods, and to form mutual aid societies. Civil disobedience has developed beyond what Thoreau probably could have imagined. Sprung from a simple act of tax refusal and a single night in jail, for all that this little idea of civil disobedience has accomplished -- for all the people that this idea has liberated, spiritually and physically -- we hope that Thoreau would be proud. Sources: “Henry David Thoreau: A War Tax Resistance Inspiration” https://nwtrcc.org/2014/07/10/henry-david-thoreau-a-war-tax-resistance-inspiration/ “Thoreau and ‘Civil Disobedience’” https://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/thoreau-and-civil-disobedience Whitman, Karen. “Re-evaluating John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry” http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh34-1.html Thoreau, Henry David. “Resistance to Civil Government.” Ed. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. Aesthetic Papers. https://archive.org/details/aestheticpapers00peabrich/page/n209/mode/2up Thoreau, H. D., letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson, February 23, 1848. http://thoreau.library.ucsb.edu/project_resources_additions/c1.344-350.pdf For this week’s Peace of History:

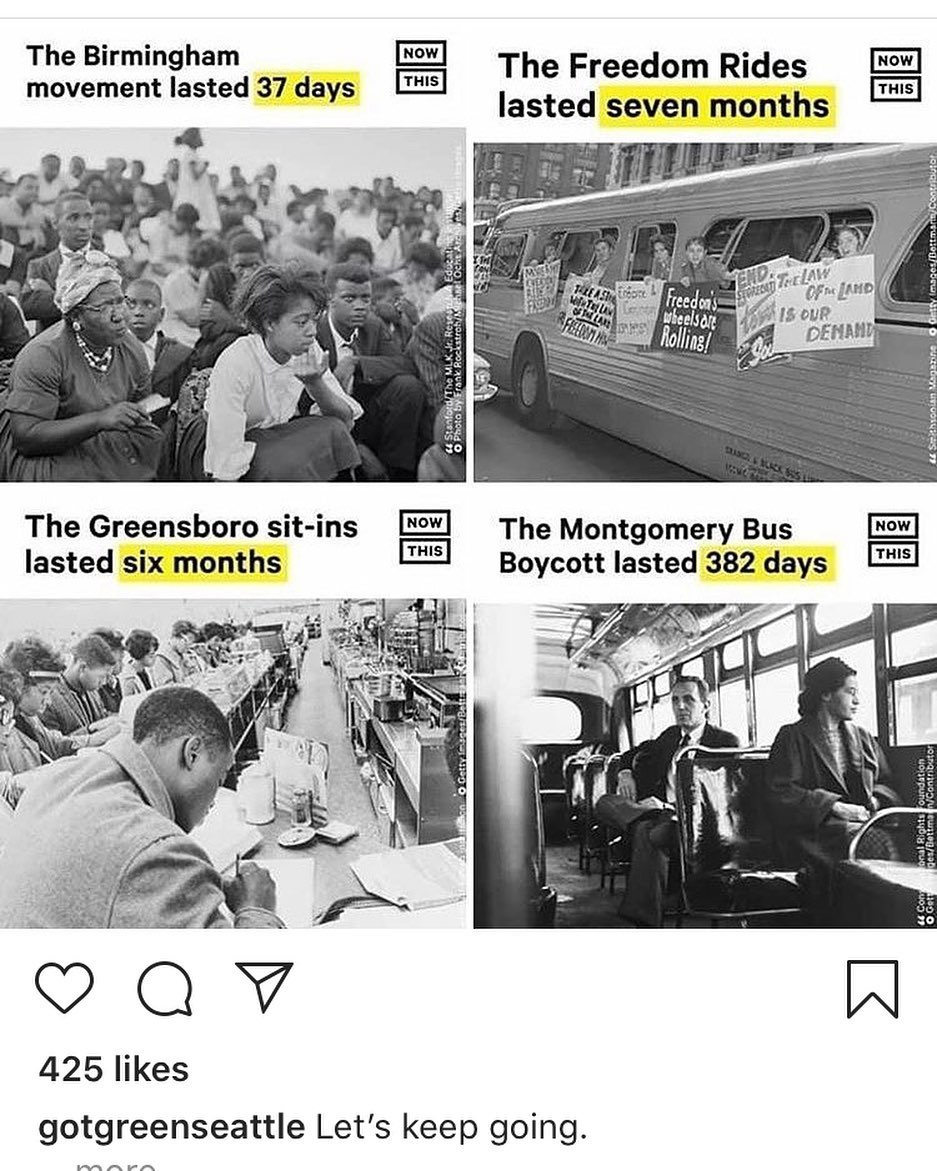

Fifty-six years ago today, the US Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law. This landmark legislation outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; enforced the equal application of voter registration requirements; and prohibited racial segregation in schools, employment, and public accommodations -- signaling an end to the Jim Crow era in the Southern United States. Most of us know the basic touchstones: Rosa Parks, Dr. King, lunch counters and buses, marches and hoses, “I have a dream…” But those are the singular, dramatic, snapshot moments we know from photos, transcripts, and mythology -- compressing a long and still-unfinished movement into a mythical long-ago. As we look around today, with a catastrophically mismanaged pandemic, a looming financial collapse, and decades of racist police brutality and incarceration serving as the backdrop of the beginning of a new social justice uprising -- it is easy to lose a sense of how much time and work it takes to achieve justice. Social movements can last for years, even decades, and are composed of several interrelated campaigns, one often inspired by another. Campaigns have specific goals, and achieving those goals can take weeks or months of sustained effort -- and all that takes organizing and time. About three weeks ago, Instagram user gotgreenseattle posted an image reminding us of that fact. Let us meditate on how long these famous historical campaigns lasted, and what it might have been like to be in the participants’ shoes:

At this moment, we are writing a new chapter in the history of civil rights in this country. After Rosa Parks’ arrest in 1955, people across the country were inspired to participate in direct action campaigns for racial justice for the next 9 years and beyond, forcing the conscience of the country to face its racist reality and getting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed. Similarly, activists across the country have been pulling down or forcing the removal of racist statues from public areas in the wake of the George Floyd protests -- after years of debate, there’s been a tidal shift, and now statues are coming down left and right. Things seem to be happening so quickly these days -- and in a sense, they are. But if we want this movement to go beyond mere symbols, we must organize and press on with more campaigns and more demands. The time for sign-waving protest is drawing to a close; it is time to learn, organize, and take action. NOTE: On June 15, 2020, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protection against workplace discrimination based on sex also applies to gay and transgender workers. This decision was announced days after President Trump announced the removal of nondiscrimination protections for trans and gender nonbinary people with regards to healthcare and health insurance -- in the middle of a pandemic. The only way to protect trans, nonbinary, and all vulnerable people is to organize, take action together, and strap in for the long haul. Sources: “Birmingham Campaign” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/birmingham-campaign “Civil Rights Law Protects Gay and Transgender Workers, Supreme Court Rules” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/15/us/gay-transgender-workers-supreme-court.html “CORE Volunteers put their lives on the Road” http://www.core-online.org/History/freedom%20rides.htm “Freedom Rides” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/freedom-rides “Montgomery Bus Boycott” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/montgomery-bus-boycott “Sit-ins” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/sit-ins “Transgender Health Protections Reversed By Trump Administration” https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/06/12/868073068/transgender-health-protections-reversed-by-trump-administration |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed