|

(click here to view the original post on Facebook)

For this week’s Peace of History: We share a brief history of ACT UP, the queer health advocacy group whose work helped save countless lives during the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. In early March, 1987, as the Reagan administration continued to cruelly neglect the rising body count of the new deadly disease, activists from the NYC queer community formed the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP). From its beginning, ACT UP was decentralized and leaderless, diverse in race and gender, followed nonviolent principles, and performed radical direct action and civil disobedience. This generation of activists was inspired by and trained by members of the civil rights, feminist, and peace movements of the previous decades. Jamie Bauer, a nonviolence trainer with the War Resisters League (WRL), encouraged ACT UP to put members through trainings to prepare for actions, to take care of each other, and to "use their bodies as a force for change." Jamie was one of many who learned their training skills from WRL. Almost exactly 33 years ago on March 24, 1987, ACT UP held their first protest on Wall Street, demanding greater access and affordability of experimental HIV/AIDS medicine from the pharmaceutical industry. Within the year, more chapters began forming in other cities across the country. In its heyday, the wholly grassroots organization took on the FDA’s excessive drug approval process for life-threatening conditions; the CDC for its narrow and inaccurate definition for AIDS; the NIH for its lack of urgency addressing the epidemic as well as its inaccurate reporting of cases; various presidents and other elected officials for their inaction, mismanagement, or divestment from life-saving programs; health insurance companies for discriminating against people with HIV/AIDS; the Catholic Church for its opposition to safe sex education in schools; and more. Even after ACT UP activity slowed elsewhere in the country, in 1996 ACT UP Philadelphia organized and applied enough pressure on Congress and the UN to force them to make HIV/AIDS medicine affordable worldwide as well. In this time of extreme uncertainty and federal ineptitude, let us take inspiration from the recent past: let us (virtually, or while practicing social distancing) join together, organize, give mutual aid, and demand justice from the powers that be in radical and creative ways. We are not powerless. To read the full story of ACT UP, please check out the two articles linked below. “ACT UP Was Unofficially Founded 33 Years Ago, Changing the Face of Queer Activism.” https://hornet.com/stories/act-up-history/ “Early AIDS Activism Was So Much More Diverse Than Media Depicts It.” https://www.out.com/…/early-aids-activism-was-so-much-more-… Source: “ACT UP ACCOMPLISHMENTS – 1987-2012.” https://actupny.com/actions/ (click here to view the original post on Facebook)

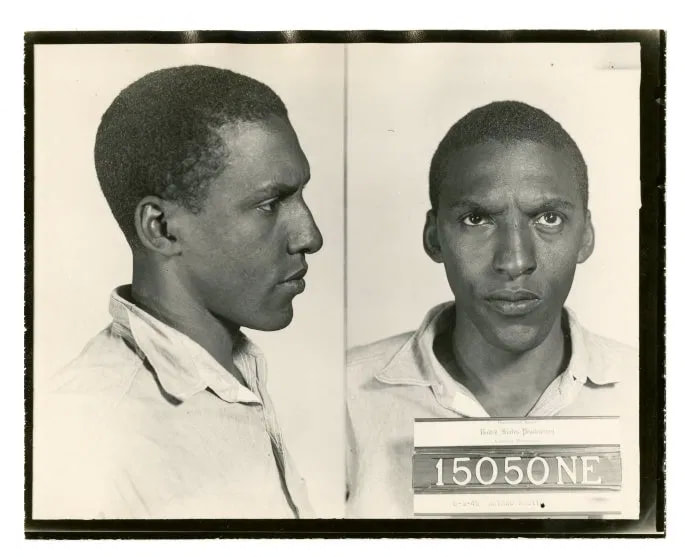

For this week’s Peace of History: In acknowledgment of Bayard Rustin’s 108th birthday and our recent theme of conscientious objection, we will highlight Rustin’s conviction and courage as a conscientious objector during WWII. Much has been done in the past couple decades to elevate heroic stories of African-Americans in the armed forces, as well as black veterans' roles in inspiring the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. But little has been shared of the stories of African-Americans who just as bravely refused compulsory military service at the same time, and who had laid the foundations for the civil rights movement before black vets came home en masse. As Matt Meyer with the War Resisters League wrote on Rustin’s centennial anniversary: “It is important first to note that, just as the foundations for much of the 1950s tumult around civil rights were laid by the Tuskegee Airmen and other members of the U.S. Armed Forces of African descent, Rustin was a part of another grouping of World War II veterans. When the black vets who helped liberate Europe from fascism and open the doors of the concentration camps came home to find that democracy and equality was not forthcoming despite their heroic efforts, Rustin and his World War II conscientious objector colleagues had spent their war years behind bars. Many of them, including Rustin, Dave Dellinger, Ralph DiGia, George Houser and Bill Sutherland, were active in efforts to desegregate the federal prisons they were held in, a daring effort 10 years before the widespread lunch counter sit-in and bus boycott campaigns.” Like many other conscientious objectors before him and since, Rustin was imprisoned from 1944-1946, for his refusal to register with the Selective Service Board. For Rustin, refusal to join the war effort was not merely about the injustice of war itself, but moreover, as he wrote in a letter to his local draft board in 1943: “Segregation, separation, according to Jesus, is the basis of continuous violence… Racial discrimination in the armed forces is morally indefensible.” According to Shaina Destine at the National Archives, Rustin’s prison file upon admission into Ashland Federal Correctional Institution on 1944 states: “...it is believed that this inmate will continue to bring up racial problems in this institution, as has been his practice before being committed here, and it is further indicated by his actions that he is already engaged in practices of agitating other inmates on the race problem. His adjustment in this institution is doubtful.” Indeed, before his arrest, Rustin had trained with the American Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia and had become involved in several racial justice efforts, including with the Harlem Ashram. (See the January 30th Peace of History for more on the Harlem Ashram.) As suspected, Rustin did not tone down his beliefs and behaviors much in prison. He was frequently disciplined for “arousing and agitating” the other prisoners about medical care, mail policies, and racial integration. From his prison file: “...this inmate objects to institutional ruling in not allowing Whites and Negroes to intermingle in so far as eating and sleeping is concerned. He will not walk in a line segregated or be segregated in the dining hall. Today at noon meal he came out with the Qurantive group but refused to line up with the Negroes, but instead started to deliver an oration on his opinions of segregation, etc. He was told to line up as required…but this he refused to do and then had to be excorted [sic] back to his cell.” In March 1946, Rustin began a hunger strike to protest racial segregation in prison. Support for Rustin among the prisoners and some sympathetic correctional officers broke when word of his homosexuality got out, but this did not break him. Rustin would go on to rack up ten disciplinary reports, finally forcing the Chief Medical Officer to designate Rustin as not “suitable for a correctional institute.” Rustin was transferred to a farm labor camp, but shortly after, Rustin was offered a conditional release with travel and publicity restrictions. He refused, citing his need for both freedoms to perform his job as field agent for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Some of these restrictions were removed. Yet, when the warden warned Rustin that he must at least try to conform to some of the other conditions for his release, Rustin refused again. In the end, the warden had to sign for him, and Rustin refused even the suit they had chosen for his release. Many have argued that WWII was a justified and necessary war for the United States to fight, and that the alternatives, fascist and imperial rule, were objectively worse. But Bayard Rustin’s resistance to participating in the Second World War highlights the essentially hypocrisy of U.S. involvement in the war: the fact that even while fighting Nazi racism abroad, America continued to racially segregate in the prisons and the barracks. Indeed, it was exactly this national cognitive dissonance, this mismatch of moral messaging and policy, that drove so many black vets to the post-war civil rights movement -- but it was conscientious objectors like Bayard Rustin who led the way. Next week: we will look into the government failure to respond during the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the grassroots organizing that gave rise to direct action groups like ACT UP. Sources: Destine, Shaina. “Bayard Rustin: The Inmate that the Prison Could Not Handle.” https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2016/08/16/bayard-rustin-the-inmate-that-the-prison-could-not-handle/ Mascari, John. “U.S. Conscientious Objectors in World War II.” https://www.friendsjournal.org/u-s-conscientious-objectors-world-war-ii/ Meyer, Matt. “Remembering Bayard Rustin at 100.” https://wagingnonviolence.org/2012/03/revisiting-rustin-on-his-centennial/ For this week’s Peace of History:

On March 10, 1987, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights officially determined conscientious objection to military service to be a human right. The men and women who founded the CNVA “Peace Farm” (that became the Voluntown Peace Trust) identified as conscientious objectors, and many more involved with VPT over the years have identified similarly. Most men deeply involved with the CNVA and VPT had resisted being drafted into the military during the Vietnam War, and women resisted war and militarism by other means, as we shared in last week’s post. In recognition of the UN decision and VPT’s own history, let us analyze the meaning of conscientious objection today. Conscientious objection has a history at least a few hundred years long in the western world, largely based off of the beliefs of pacifist religious minorities. Historically, conscientious objection meant supporting a state’s war effort by means other than military service: usually alternative labor or an additional tax. Where C.O. status was not legally granted, C.O.s faced incarceration, and sometimes execution. Most modern states have granted some recognition to conscientious objection, usually granting “exemptions” from military service and assigning alternative labor in service to the state. And yet even this practice is fraught with problems. What are the limits to “exemption” to military service within the context of an economy built around an unfettered military-industrial complex? And so it is significant that on multiple occasions following its initial adoption in 1976, the UN has reiterated the official interpretation of Article 18 of the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as including conscientious objection to military service. Article 18 defends “the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” However, it is worth examining the exact recommendations and requests that the UN laid out in the 1987 decision. Included are appeals to “exemption from military service on the basis of a genuinely held conscientious objection” and the establishment of “impartial decision-making procedures to determine whether a conscientious objection is valid” (emphases added). But by what measures and tools can a state judge the authenticity of one’s moral beliefs? The nebulousness of defining “genuine” conscientious objection is a major problem. Under current United States law, conscientious objection is defined as: “A firm, fixed, and sincere objection to participation in war in any form or the bearing of arms, by reason of religious training and/or belief.” The GI Rights Hotline (linked in the sources) does an excellent job of deconstructing this definition. But the interpretation of the definition, and thus the judgment of one’s authenticity, is ultimately up to one’s local board, a mental health specialist, a military chaplain, and an investigating officer -- all connected to the military. The terms “training and/or belief” is especially troubling, as they imply a kind of consistency that excludes personal growth and revelatory experiences. The term “religious,” too, is confusing especially since it is meant to encompass more than just “traditional religious beliefs,” but not to include “political, sociological, or philosophical views.” Which then begs the question: what kind of ethical argument to defend conscientious objection does not rely on religion, politics, sociology, or philosophy? To a certain extent, attempting to define conscientious objection is a rhetorical trap for those already resisting war. One former member of the US Army, Stephanie Atkinson, begins her account of going AWOL before Operation Desert Storm by stating, “I am not a conscientious objector. I am not someone who has had to defend my beliefs for not participating in war. I am someone who when called upon to participate in a war that I thought was unjustifiable for many reasons, refused to go.” She goes on to describe her reasons as “political” but also as “murky” and coming from “feelings and experiences that indicated to me that my participation in the first Gulf War would be wrong.” But for those who did not grow up in a religious tradition, activist community, or other pacifist organization -- for those who reach the decision to resist military participation through later life experiences -- how can they defend their beliefs as legitimate to the military itself? And by what right can anyone say that their new beliefs are any less authentic as a lifelong acolyte of faith? Another resister, Diedra Cobb, describes the difficulty of gaining C.O. status in the contemporary U.S. military. Having begun basic training in January 2002, Cobb immediately realized that the violent chants and the actual weapons trainings, alongside the absolute dearth of cultural understanding of other peoples was all very disturbing to her. Within a few months after training, Cobb’s perspective was solidified even further by reading a book by Julia Alvarez. Deceived into reporting for duty, Cobb was sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland with her C.O. papers in hand, and then deployed to Iraq. After months of bureaucratic stalling, false threats by an ambitious commander, and a sexual assault in the barracks, Cobb returned home in December 2003. After all that, her C.O. case was denied, and she began working with a lawyer to defend her objection if she were to be called upon again. The difficulty Cobb describes in her story is unfortunately not uncommon. And so we return to the question of what conscientious objection means today. In practice, the term is quite arbitrary and is in a very real way defined by the body to which the term objects. Indeed, the United Nations acknowledges certain limitations on the rights to freedom of thought, including those “necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.” While clearly written to curtail and delegitimize violent or oppressive personal beliefs, that caveat can just as easily be misapplied by a sufficiently motivated military to coerce C.O.s to participate in war more directly. Therefore, for those not already in the military, sometimes other types of resistance are more effective. Perhaps the most familiar type of draft resistance is simply to fail to show up when called to serve. When the draft is inactive, some refuse to register with the Selective Service at all. And for those who awaken to their conscientious objection while already in the military, but who are then denied C.O. status, refusing to obey orders or even desert may be their only options so that they do not violate their conscience. Next week: we will look at what happens when one objects to even indirect participation in war, including the story of Bayard Rustin’s resistance in WWII. Sources: Elster Ellen and Majken Jul Sorensen, Editors. “Women Conscientious Objectors: An Anthology.” War Resisters’ International, 2010. “Conscientious Objection: Fact Sheet.” https://girightshotline.org/en/military-knowledge-base/topic/conscientious-objection-discharge “Conscientious objection to military service.” https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/RuleOfLaw/Pages/ConscientiousObjection.aspx “Conscientious objection to military service.” https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f0ce50.html “Conscientious Objector.” https://www.sss.gov/consobj “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.” https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx (click here to view the original post on Facebook)

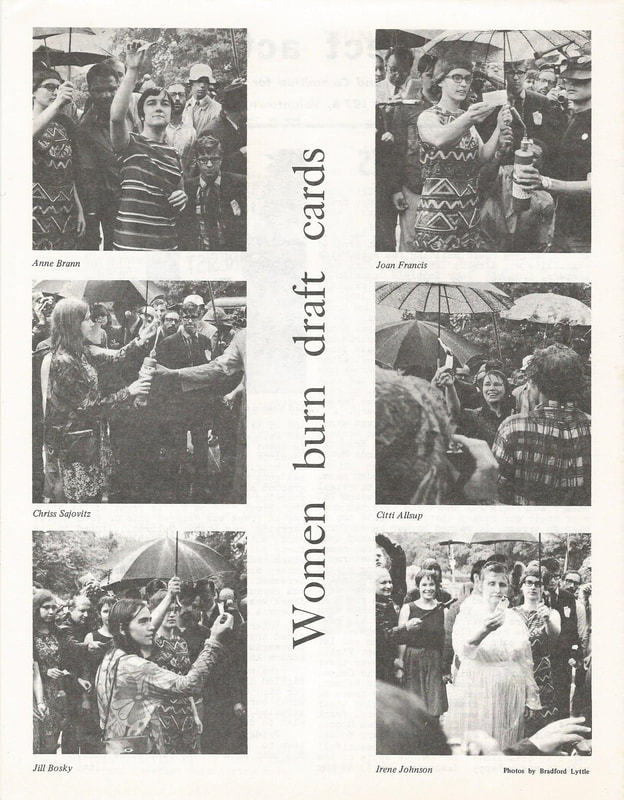

For this week’s Peace of History: In acknowledgement of International Women’s Day on March 8, we will share stories of women’s direct resistance to military service. Some resisted their own service, after enlisting under false assumptions, misconceptions, or outright deceit. Others have put themselves at risk of arrest and bodily harm to resist as surrogates for others. And still others have made themselves into roadblocks to hamper the draft effort. One woman, Jean Zwickel, lost her job as a teacher for refusing to conscript students during World War II. She joined the Harlem Ashram, then the greater peace movement, remaining a dedicated activist into her eighties. Another woman, Erna Harris, a member of the War Resisters League and the Fellowship of Reconciliation, risked arrest and worse when she and a friend encouraged the “guys from the camp” to either apply for conscientious objector designation or to go “over the hill” and desert. Harris, a black woman and journalist who continued to be active in the pacifist and civil rights movements years later, provided shelter and aid to C.O.s and deserters. From her own words, “What we women were mostly doing was trying to take care of the guys who went to camp and make sure they didn’t feel deserted, which was easy to feel, and to take care of the ones who didn’t get their classification or who decided not to register and, therefore, were in trials or on their way to prisons.” Years later, as the draft returned during the Vietnam War, the Committee for Nonviolent Action staged a remarkable protest in Washington, D.C. On June 19, 1968, under umbrellas and plastic coverings at the foot of the Supreme Court Building, several men handed over their draft cards to their female co-conspirators, who lit the cards ablaze with a little propane torch. The women and some men over the draft age again put themselves at risk of arrest and injury to voice their opposition to compulsory military service. Exemption from the draft did not include exemption for the penalty of burning a draft card. Several of these activists, including Mary Suzuki who lived a CNVA in Voluntown (predecessor to VPT), were subjected to being dragged by their hair and clothes by police as activists nonviolently obstructed the arrests of their fellow protesters. Others were arrested later, when police forcibly broke into a church, interrupting a nonviolent resistance training for teens and adults. Our society is changing rapidly, and some in more recent times have argued that true gender equality would also mean that women should have to register for selective service alongside men -- otherwise, those proponents say, the feminists’ call for gender equality is revealed to be disingenuous. And yet in the past decade alone, at least 20-32% of female service members have been sexually assaulted by other service members, often by officers and senior staff. Accurate numbers are difficult to attain, but several surveys have determined that while sexual assault in the armed forces is at least twice as high as in the general public, it is also extremely underreported, and even fewer reports result in convictions. At least half of those who report assault have suffered some form of retaliation by their superiors, and some have been dishonorably discharged for reasons relating to the assault. The entire premise of the military is built upon authoritarianism and patriarchy. To impose the draft on more people would only serve to expand and reinforce such an institution, and to impose the draft on women would especially reproduce and amplify the worst elements of toxic masculinity in the world. If the choice between gender-neutral selective service and the dismissal of gender equality is a false dichotomy, so is the choice between being a “Rosie-the-Riveter” and a helpless maiden as one’s country decides to go to war. For some years now, there has been an increased effort to promote and celebrate stories of women’s contributions to great national war efforts on the “homefront”: working in factories to replace the male workers, caring for families and children who have lost their main breadwinners, and generally maintaining the social fabric of their communities. And yet, little has been made of the converse: the remarkable women who resisted war, militarism, and selective service with action or noncompliance, even when it may have been easier to comply. May those women who resisted be an inspiration for us, as they show us that to have inner strength means to remain true to our convictions even when there is no immediate threat to us personally. Next week, we will discuss the various reasons for conscientious objection, the different paths that have led many to pacifism, and what it means for the United Nations to have deemed conscientious objection as a human right. Sources: Allsup, Citti. “Sisters Say Yes.” Direct Action for a Nonviolent World. New England Committee for Nonviolent Action, June-July 1968. Elster Ellen and Majken Jul Sorensen, Editors. “Women Conscientious Objectors: An Anthology.” War Resisters’ International, 2010. https://www.newsweek.com/militarys-secret-shame-66459 https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/02/us/military-sex-assault-report.html?_r=0 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/01/military-sexual-assault-reports-soar-pentagon-report Photos from Direct Action for a Nonviolent World, June-July 1968. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed