|

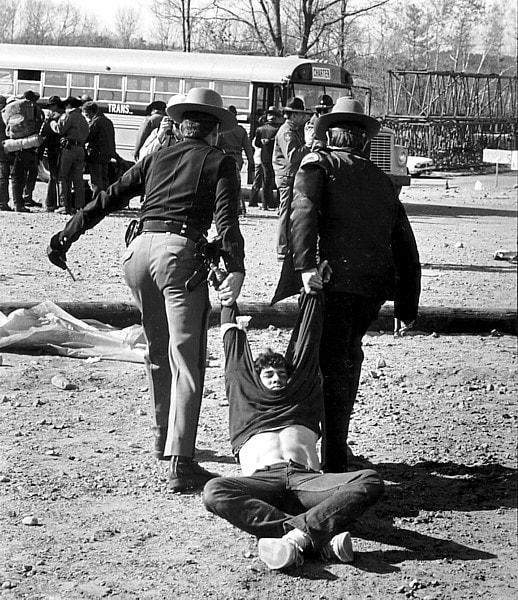

On April 30, 1977, over 2400 people gathered at a construction site in New Hampshire to protest the building of the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant. The coalition of activists called themselves the Clamshell Alliance, referring to the native clams endangered by the building of the power plant. Every single attendant had been trained extensively for this action. It was not the first time these organizing practices had been used; such ideas had been implemented widely in the antiwar movement and had been used organically by peoples all over the world for time immemorial. Nor was it the first time someone had objected to the project plan at that site; for years, community members had been using traditional legalistic tactics to stop the construction plan, and local activists had already held two smaller-scale occupations of the site the year before. But the protest in April-May 1977, less than a year after the Clamshell Alliance had formed, proved to be a watershed moment that has shaped the form of leftist organizing in much of the United States and Europe up to the present day.

Inspiration for the Clamshell Alliance came from the activities of two communities on opposite sides of the Rhine River. There, the French and German communities worked in solidarity to nonviolently occupy the construction sites of a lead factory and a nuclear power plant, successfully halting the building of both facilities. Back in New Hampshire, when the local community’s traditional legalistic strategies to stop the construction of the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant failed, activists began planning their own occupation of the building site. In April 1976, organizers invited American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) member Suki Rice to train activists for the first protest action. One striking detail to note is that the Clamshell Alliance actively sought the expertise of extraordinary women who had much experience from their work in other social movements. Suki Rice had received her training from Marj Swann, co-founder of CNVA and the Voluntown Peace Trust (which sent the affinity group Millstone Mollusks to the 1977 Clamshell occupation). Swann, in turn, received her training as a charter member of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942, and led trainings alongside civil rights leader Bernard Lafayette, one of the student-activists of the trailblazing 1960 Nashville sit-in campaign. Activists announced the formation of the Clamshell Alliance in July 1977 and made plans to occupy the power plant’s construction site in August. At the first action, 18 activists were arrested. At the second action later that month, 180 people were arrested. Organizers realized the need for all attendants to undergo extensive and specific training before participating in any given action, especially if they wanted to also scale up the occupation. They invited Suki Rice, fellow trainer Frances Crowe, and others back to give those trainings, but shortly after the first action, it became clear that more trainers would be necessary to keep pace with the growing numbers in the Clamshell Alliance. Thus, Rice and others began conducting weekend training-for-trainers so that each state and region had the persons to give such trainings as well. The basic training agenda began as a day-long program, but gradually got shorter as the date of the action neared and more people wanted to participate. Trainings included group discussions of values and actions, roleplay of scenarios involving hecklers and police, information on legal matters like arrests, consensus decision-making in affinity groups, and various other resources as handouts. The Clamshell Alliance adopted a specific set of organizing principles. The Clamshell would be organized without hierarchies or leaders in order to maintain logistical flexibility. As mentioned, Clamshell activities would be strictly nonviolent: all participants agreed to a code of nonviolence, and organizers ensured discipline among participants with the extensive trainings delivered by Rice, Crowe, and others whom they trained. In the same nonhierarchical spirit, the Alliance organized itself by “affinity groups”: small autonomous groups of about 6-20 persons who already know each other and have some common bond. Affinity groups were inspired by Spanish anarchist cells, women’s consciousness raising groups, and had been used to some degree in the U.S. by the Vietnam-era antiwar movement, in which many Clamshell activists had participated previously. The Clamshell organizers also adopted the consensus decision-making process learned from Suki Rice and others in the AFSC. In the consensus process, participants take no action without the consent of all members. Affinity groups were trained in the consensus process for all their meetings. To coordinate between affinity groups the concept of the “spokescouncil” formed. In the spokescouncil system, each affinity group would choose a representative from among the group to join in a circle of “spokespeople” to coordinate. The representatives would then return and consult with their respective affinity groups. These organizing principles were described in handbooks. Setting all these principles early and ensuring that all participants were trained in those principles proved to be essential, especially at the April 30, 1977 occupation. With over 2400 activists preparing to camp at the construction site, everyone had to be on the same page. But within the next two days, 1415 of the occupying activists were arrested. Jail solidarity, including the mass refusal of bail, had been a part of the trainings everyone received, and everyone maintained their discipline. Some were held in National Guard armories for two weeks. Locked up in such close quarters, their morale buoyed by the mental and physical preparations they had previously made through training, some used the close quarters and extended time together for even more training and cross-pollination of ideas between various affinity groups. Although one of the two Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant was eventually built, the antinuclear movement that developed in the preparations for April 30, 1977 as well as during the two weeks after their arrests proliferated and became so effective that no new nuclear power plants have been built in the United States since. No one could have known it at the time, but the trainings that were held, the handbooks that were printed, and the relationships that formed during the April 30, 1977 occupation reverberated longer and wider than anyone expected. Later in the same year, activists in central California, on the other side of the continent from Seabrook, formed the Clamshell-inspired Abalone Alliance to shut down the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in much the same way that Clamshell had. Over the next few years, the War Resisters League (WRL) would spread the Clamshell model that included affinity groups trained in consensus and nonviolence guidelines to many other groups around the country. In 1979, some WRL members who participated in the Clamshell Alliance formed the SHAD Alliance in Long Island, NY, using those principles to organize a successful campaign against the construction of the Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant. In 1982, during the United Nations’ Special Session on Disarmament, close to a million people gathered in New York City to demonstrate for nuclear disarmament. WRL organized mass actions among the incredibly diverse collection of people, spreading the Clamshell principles to an even greater number of activists. ACT UP, the grassroots HIV/AIDS activist group that began in 1987, also organized their movement around these principles to great success. In 1989, WRL published the Handbook for Nonviolent Action, which was updated and extended in the new text, Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns. By the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, concepts like the consensus process, affinity groups, spokescouncils, and pre-action trainings were so widespread that anarchist groups were quickly able to organize and mount disruptive civil disobedience and other actions. And in 2011, when the Occupy Wall Street movement began, those same organizing principles used by the Clamshell Alliance maintained the camps and directed mass actions. Now that a new generation of activists has formed since the George Floyd protests, it is important to review watershed moments like the Clamshell Alliance 1977 occupation in order to learn effective organizing practices and to understand how these practices were forged and proven. It is a terrible waste of time and resources to attempt to reinvent the wheel -- or the spokescouncil. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Asinof, Richard. “No-Nukers Demonstrate Their Strength at Seabrook.” Valley Advocate. Published May 11, 1977 (accessed 28 April 2021). https://archive.is/20030706050409/http://old.valleyadvocate.com/25th/archives/seabrook.html “Clamshell history.” To the Village Square. (accessed 28 April 2021). https://web.archive.org/web/20070629024709/http://www.clamshell-tvs.org/clamshell_history/index.html Rice, Sukie. “As I Recall It.” Clamshell Alliance. (accessed 28 April 2021). https://www.clamshellalliance.net/legacy/2010/03/06/as-i-recall-it-by-suki-rice/ “Seabrook, NH Nuclear Plant Occupation Page.” Updated 18 February 2012 (accessed 30 April 2021). https://www.marcuse.org/harold/pages/seabrook.htm Sheehan, Joanne. “Practicing Nonviolence.” War Resisters League. Published originally in The Nonviolent Activist, July-August 1998 (accessed 28 April 2021). https://www.warresisters.org/decades-nonviolence-training Sheehan, Joanne and Eric Bachman. “Seabrook-Whyle-Marclolsheim: transnational links in a chain of campaigns.” https://www.nonviolence.wri-irg.org/en/resources/2008/seabrook-wyhl-marckolsheim-transnational-links-chain-campaigns Today we mark the fifty-first Earth Day, an annual event to celebrate, promote, and educate the public about healthy ecologies and the environmental protections that sustain them. Since 1970, Earth Day has expanded far beyond its original scope, birthing the modern environmental movement, becoming an international holiday in 1990, and gaining renewed urgency with the acceleration of global climate change in the 21st century. Yet, Earth Day now is too-often reduced to small, single issues and individual responsibility. While there is nothing wrong with promoting recycling, reducing energy consumption, and picking up litter (indeed, VPT will be joining Voluntown’s downtown clean-up event this Saturday morning), such actions alone are inadequate to address the global existential threat that climate change poses. Environmentalism has also become severely politicized, as most dramatically evidenced by the Trump Administration’s reversal and rollback of more than 100 environmental protections in just four years. Therefore, on this anniversary, let us examine how and why the first Earth Day came to be, what occurred on that day, and what happened as a result.

A few seemingly unrelated events led to the invention and success of the first Earth Day. In 1962, the great media theorist Marshall McLuhan coined the term “global village” to describe the increasing interconnectedness of the modern world. That same year, biologist Rachel Carson published her groundbreaking book Silent Spring, which revealed the ecological dangers caused by massive and indiscriminate use of pesticides. Thanks to the attempts of industrial chemical companies like DuPont, who attempted to discredit Carson while the work was still in pre-print, Silent Spring published with massive publicity. Within just a few years, Silent Spring had inspired countless people, especially in the scientific community, to think more critically about the greater consequences of modern scientific intervention in the natural world: in time for much of the American public to feel disturbed at the news of their government using Agent Orange and “defoliation” tactics in the Vietnam War. Then, in 1968, NASA’s Apollo 8 mission successfully sent a team of astronauts around the moon and back for the first time, returning with the first color photos of Earth from space taken by a human being; included in the photo set is the famous Earthrise image. That iconic photo of the singular, majestic blue and white orb rising out of the infinite shadows of the Moon has been called “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken.” It has evoked awe and wonder since Americans first saw it in 1968. But that beautiful image of the Earth fell into stark relief against the realities of unfettered resource extraction and pollution just a month later. In late January 1969, an offshore oil drilling accident off the coast of California resulted in the Santa Barbara oil spill, the worst oil spill in U.S. waters up to that time. For over two months, crude oil under immense pressure bubbled up from the seafloor, poisoning and killing an untold number of birds and sea life. Commercial fishing around the area was halted, beaches were blackened with oil, and the bodies of dead marine mammals and birds started to wash ashore at an alarming rate. The ecological damage was shocking enough to prompt an enormous public response even before anyone knew the full extent of the disaster. Soon, hundreds of volunteers were trying to absorb the oil in the water and on the beaches with massive quantities of straw and detergent. Workers in bulldozers removed contaminated sand. Airplanes hastily dumped chemical dispersants over the spill to hasten the clearing process. After 45 straight days of cleaning efforts, most of the area was cleared of oil, but the leak continued for the rest of the year, and the negative effects of the spill continued to manifest. It was all of these factors converging at once that sparked the idea for what would become Earth Day. The concept started in mid-1969 with Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson as a day of teach-ins at colleges across the United States. Inspired by the student activism of the 1950s and 1960s civil rights movement and the antiwar movement, Senator Nelson formed the nonprofit Environmental Teach-In, Inc. with bipartisan support and hired Harvard graduate student Denis Hayes to serve as National Coordinator of the entire campaign. But by 1970, the concept of the teach-in already seemed outmoded to some, and the “Environmental Teach-In” name was having little success in inspiring participation. Then, a successful ad-man named Julien Koenig offered to help with the campaign, ultimately proposing the name “Earth Day.” The new name was immediately adopted nationwide, and magazines and newspapers ran Earth Day ads advertisements under the new name brought in donations from thousands of supporters and potential participants. The supporters, however, were more than just college students: letters and donations came in from K-12 teachers, housewives, and especially organized labor. Educational materials were produced and distributed for classrooms and community events. Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers and a firm supporter of the civil rights and antiwar movements, had personally made the first donation to the campaign within the first week of its announcement; he would go on to direct his union to fund all of the printing and mailing of Earth Day materials, to fund all of the phone lines between organizers across the country, and encouraged workers in every participating city to join Earth Day events. On April 22, 1970, twenty million people across the United States demonstrated at more than 12,000 Earth Day events in support of increasing environmental protections: 20 million people disturbed by the findings about ubiquitous pesticides in Carson’s Silent Spring, moved by the far-away splendor of the Earthrise photo, horrified by the loss of animal life from the Santa Barbara oil spill, or otherwise compelled to stand against preventable ecological damage. It was the largest demonstration for environmental protections in history, and rather diverse in how they were conducted. Some purposely evoked the catastrophic oil spill from the year before. One group dumped oil-coated rubber ducks in front of the Department of the Interior, while another dragged dead fish in a net down New York City’s Fifth Avenue. Others focused on related topics like the energy industry as a whole, or industrial pollution from factories. In some places, the mood was warm and cozy; at others, intense and carnivalesque. The events proved to be so popular that many were extended through the week. Several colleges, where most of the activist energy was usually directed toward the antiwar movement, ended up holding some environmental teach-ins after all. The first Earth Day, with its joyous mix of theatricality, education, and community unity, changed the lives of many Americans. Among those who experienced that change was the staff of Environmental Teach-In, Inc. who resigned after the first Earth Day and formed a new group, Environmental Action. But some politicians were also compelled by the intensity of the burgeoning environmental movement to take action. Due to the environmental concerns that had been growing since Silent Spring was published, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was the first bill of 1970 that President Nixon signed into law. Within three months of the first Earth Day, and in part because of its success, Nixon sent a proposal for a new independent agency of the federal government to coordinate the objectives outlined in the NEPA, and before the year was out, the Environmental Protection Agency was already sending notices to cities to comply with new regulations or else face federal lawsuits. As the first Earth Day shows, marching and picketing are not the only effective collective actions available to us. Working in conjunction with educational literature, emotionally moving art, community events like teach-ins, good media coverage, and a diverse range of interested parties from the community, political demonstrations can be celebratory events in which people are reminded of the things in life worth preserving. The first Earth Day also shows that protest is often most effective when a plurality of the public takes part. Without all the different kinds of people who stepped up to support the campaign -- housewives, union members, teachers, students, ad-men and politicians from both major parties -- Earth Day would have been over before it started. Now, we look back on a troubled recent past and face ahead an uncertain future. The Paris Climate Accords have largely failed to curb global climate change, even as the covid-19 pandemic kept so many sequestered at home. Earth Day may have started with a focus on the United States, but to truly address the greater concerns to which Earth Day points, we will need robust, intense international cooperation -- and in all likelihood, a globe-spanning network of groups and individuals to collectively pressure their respective governments. Luckily, much of that groundwork has already been done. Today is the 51st Earth Day. The movement is already here. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources “Earthrise.” NASA, (accessed 21 April 2021). https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_1249.html Hill, Gladwin. “EARTH DAY THEME CONTINUES IN U.S.” The New York Times, 24 April 1970 (accessed 21 April 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/1970/04/24/archives/earth-day-theme-continues-in-us-antipollution-activity-goes-beyond.html Lewis, Jack. “The Birth of EPA.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, (accessed 21 April 2021). https://web.archive.org/web/20060922192621/http://epa.gov/35thanniversary/topics/epa/15c.htm Popovich, Nadja, Livia Albeck-Ripka, and Kendra Pierre-Louis. “The Trump Administration Rolled Back More Than 100 Environmental Rules. Here’s the Full List.” The New York Times, updated 20 January 2021 (accessed 21 April 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/climate/trump-environment-rollbacks-list.html Rome, Adam. “Earth Day 1970 was more than just a protest. It built a movement.” The Washington Post, 22 April 2020 (accessed 21 April 2021). Yeo, Sophie. “How the largest environmental movement in history was born.” BBC, 21 April 2020 (accessed 21 April 2021). https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200420-earth-day-2020-how-an-environmental-movement-was-born A little less than fifty years ago in 1971, over 800 Vietnam War veterans gathered in Washington, D.C. and ceremonially threw their medals, ribbons, and other markers of military valor onto the grounds in front of the Capitol. The veterans were there to protest the brutal and unwinnable war that the United States was perpetrating in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia -- the war in which those veterans earned those medals and ribbons in the first place. The story of the veterans throwing away their military honors in protest made the front page of newspapers across the country, including The New York Times, but the memory of that dramatic demonstration has largely been forgotten, the significance of the event lost, and the event itself replaced with misleading and wrongful myths about veterans’ active roles in the antiwar movement.

It is a long-standing misconception that antiwar activists and war veterans are fundamentally at odds with each other, but even just a glance at the history quickly dispels the notion. The myth of antiwar protesters spitting on returning veterans has been effectively disproven, and one of the earliest and most popular slogans in the Vietnam era movement was “bring our boys home.” Antiwar activists have always directed criticism on the political and military leadership, not the soldiers themselves; in fact, much of antiwar activity centers around supporting active-duty soldiers and veterans as they struggle with what they have been forced to do in the military. For example, the Committee for Nonviolent Action, which founded the original iteration of the Voluntown Peace Trust, offered military counseling and support for resisters. But veterans were not merely passive victims; they themselves ultimately became leaders in the antiwar movement. Exactly 55 years ago, twenty recently discharged veterans joined an antiwar protest in New York City under a banner which read: “Vietnam Veterans Against War.” Later that day, six of those veterans decided to start a formal organization to give voice to other veterans who had come to oppose the war like themselves: Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). As the war continued, membership in the organization grew, especially after a few shocking events. On April 28, 1970, President Nixon authorized US troops to cross into neutral Cambodia, illegally extending the war. Days later at Kent State University, the National Guard fired about 67 live rounds with no immediate provocation at student antiwar protesters, killing four students and injuring nine more. The massacre triggered more protests across the country and thousands to join VVAW. A few months later, over Labor Day weekend in September, VVAW conducted Operation RAW (Rapid American Withdrawal). Over 200 VVAW members, accompanied by members of other antiwar groups, marched from Morristown, New Jersey to Valley Forge State Park in Pennsylvania. Organizers had planted actors in towns along the route beforehand. When the VVAW would arrive in a town along the march route, they would conduct dramatized “search and destroy” missions with the actors, bringing the Vietnamese civilian’s war experience to American small towns’ streets. Operation RAW concluded with a four-hour rally at which future Presidential candidate John Kerry, civil rights leader Rev. James Bevel, and actor-activist Jane Fonda and other speakers addressed a crowd of over 1500. VVAW sponsored actions, investigations, and other projects to support those left out in the cold by the Veterans’ Affairs office. VVAW also continued to educate the American public about the horrible realities of the war. To serve both ends, from January 1971 to February 1972, VVAW sponsored the Winter Soldier Investigation into American war crimes that U.S. veterans witnessed or were forced to commit. The project was meant to expose the military’s lies that hideous massacres like at the village of My Lai were extraordinary cases. According to the testimonies of 109 Vietnam veterans, such atrocities committed by U.S. Armed Forces were routine. Although the testimonies were ultimately entered into the Congressional record and submitted to the Department of Defense to be used in an internal investigation, the Winter Soldier Investigation was the target of a media blackout. Therefore, the veterans’ testimonies never reached the wider public as organizers had hoped. The VVAW action in April of 1971 outside the U.S. Capitol was harder to ignore. Named “Operation Dewey Canyon III” after a series of intense U.S. Marine invasions into Laos, participants ironically described it as “a limited incursion into the country of Congress.” On April 19, 1971, the American Gold Star Mothers (an organization for American mothers whose children died in service of the U.S. military) led over 1100 veterans to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. The gates had been closed and locked before the march arrived, but that did not stop the group from holding a memorial service for the lives lost on all sides of the conflict. Over the next few days, VVAW would perform more guerilla theater search and destroy missions, attempt to surrender to the Pentagon as war criminals, and lobby congressional representatives about ending the war. VVAW spokesperson John Kerry addressed the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for two hours to testify against the war. Patriotic songs were sung. A candlelight vigil was held. The veterans also defied an injunction against camping on the National Mall and prepared themselves to be detained for it, but were pleasantly surprised when park police refused orders to make any arrests. A group of 106 veterans were later arrested for protesting the injunction on the steps of the Supreme Court, but were shortly thereafter released. Finally, on Friday, April 23, about 800 veterans lined up before the U.S. Capitol. After four days of anxiety and dramatic action, the veterans had had enough. The original plan was to put the medals, ribbons, and other military memorabilia into a body bag to deposit at the Capitol, but fences had been hastily erected to keep the veterans out. And so, in front of news media cameras and hundreds of people, the veterans formed a line. Someone played “Taps.” Then, each veteran gave their name, rank, military awards, and a few personal words before ripping off their war mementos and tossing them over the fence. Some Gold Star Mothers participated as well, throwing away the awards the military had posthumously granted to the Mothers’ children. The videos and photos that were captured that day speak to the raw fury and deep sadness, but also the profound catharsis of the action. Veterans alluded to the horrible acts for which they received commendations, the unjust reasons and propagandistic government lies that made them go to war in the first place, and the memories of those who had senselessly lost their lives. One said, “This is for my brothers.” Another named a comrade who had “died needlessly” for every medal he threw. A third tossed his commendations because they had been given to him “by the power structure that has genocidal policies against nonwhite peoples of the world.” And on and on, until the grounds before the Capitol was littered in hundreds of symbols of “ honorable military service.” Within two years of Operation Dewey Canyon III and the famous “throwing of medals” in particular, the United States would cease active military operations in southeast Asia. After the United States had left the war, VVAW continued to operate as an advocacy group for Vietnam veterans to both the government and to other veterans’ groups. VVAW also began to advocate for a blanket amnesty for draft resisters and military deserters: those who had escaped the war horrors to which so many veterans had been subjected. Due to their work, President Carter granted amnesty in 1980. Over two decades later, as the first U.S. veterans were returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan, VVAW inspired Iraq Veterans Against the War, which continues to operate as a protest and advocacy group today under the name About Face. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Hunt, Andrew E. The Turning: A History of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. New York University Press, 1999. Lembcke, Jerry. “The Myth of the Spitting Antiwar Protester.” The New York Times. 13 October 2017 (accessed 14 April 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/13/opinion/myth-spitting-vietnam-protester.html Vietnam Veterans Against the War. (accessed 14 April 2021). http://www.vvaw.org/ “Veterans Discard Medals In War Protest at Capitol.” The New York Times. 24 April 1971 (accessed 14 April 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/1971/04/24/archives/veterans-discard-medals-in-war-protest-at-capitol-veterans-discard.html Yesterday, people across the planet celebrated the 72nd World Health Day. First recognized in 1950, World Health Day is sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) to celebrate international efforts to improve people’s health and to raise awareness of a particular health-related issue. In response to the extreme social and economic inequities exposed by the covid-19 pandemic, the theme for World Health Day 2021 is “Building a fairer, healthier world.” Many are already aware of the risks and sacrifices essential workers have been forced to make in most of the United States, but less have considered the global inequity that this pandemic has exposed, or what that inequity will mean in the long term. But this is far from the first time the WHO and the global community have worked together to address a deadly common threat. Now, as the vaccines are rolling out and the end of the pandemic may be in sight for some, let us examine a few of those past instances in order to duplicate our greatest successes -- and avoid our worst failures.

By 1950, due to widespread systemic changes to modern life in many parts of the world, an invisible menace would descend upon communities in the summer months, maiming and even killing 20,000 to 60,000 people, especially children, each year. The mysterious threat was the poliovirus, and in the first half of the 20th century, the disease was mutating to become even deadlier. Incurable, highly contagious, and easily spread by asymptomatic carriers (up to 70% of those infected), polio first attacks the intestinal tract, but then moves to attack the central nervous system in about 1% of victims. Once in the central nervous system, polio can cause muscle weakness, partial paralysis, and sometimes death. Around the middle of the 20th century, three brilliant U.S. scientists led teams to track, study, and eliminate this devastating illness. The vaccines that they developed saved countless lives around the world, and one is still used today in the WHO’s ongoing international quest to eliminate polio forever. The three men most responsible for the development of these vaccines were Hilary Koprowski, Jonas Salk, and Albert Sabin. Many are familiar with the heroic story of Jonas Salk, who famously devoted two and a half years to the effort, tested the injected “killed” vaccine on himself and his family, and then famously refused to patent the vaccine so that its distribution would not be hindered. After years of trials, the Salk vaccine was approved in the United States in 1955 and saved thousands of lives. Few, however, know that Polish-born virologist Hilary Koprowski’s team developed an oral-delivery “live” vaccine first in 1950, which was never approved in the United States but saved countless lives overseas. Then, through the 1950s, Albert Sabin’s team developed a safer and more potent version of Koprowski’s vaccine, which was first approved in the United States in 1961. Before it was approved in the U.S., though, Sabin freely shared the vaccine with the Soviet Union, the rising rival to the United States, acknowledging that the polio pandemic was not just an American problem but a global one. Like Salk, Sabin never patented his team’s vaccine either. It is the Sabin-Koprowski vaccine that has gone on to be the primary vaccine used globally by the WHO today. Through international cooperation, humans have completely defeated one other viral threat to our species: smallpox, declared eradicated in 1980. Polio is likely next -- after the immense amount of attention and activity to develop and distribute a vaccine in the mid-20th century, the WHO with its regional partners have eliminated the poliovirus from the Americas, Europe, Africa, Oceania, East Asia, and most of South Asia. In recent years, the number of worldwide annual cases have reduced to a range between the hundreds and the low thousands. The main hurdle to complete eradication is regional political instability, in large part caused by violent nationalism and exacerbated by foreign interests looking to exploit the instability for their own ends. In our current covid-19 pandemic, we have seen both ugly racial prejudices cropping up as well as an immense international effort to address the global threat. The scientific cooperation has been rather inspirational, if underreported. But former President Trump pulled the United States out of the WHO just when American expertise could have assisted the global community, as covid-19 became a global pandemic. Biden has rejoined the United States to the WHO, but international inequality in the distribution of vaccines continues. Rich countries are ordering and stockpiling many more vaccine doses than their total populations -- the United States has ordered a little less than double the number of its total population -- despite the immense difficulty that many poorer countries are having in acquiring any vaccine doses at all and despite the United States’ own massive culpability in incubating and spreading the covid-19 pandemic. At the same time, “vaccine nationalism” has convinced regional political entities like the European Union to halt the export of vaccine doses to their partners abroad, while their own citizens are not fully inoculated -- despite the failure of the EU vaccine rollout stemming from poor management and a lack of infrastructure as opposed to a lack of doses. Meanwhile, as rich countries subsidize the vaccine for their own citizens, some pharmaceutical companies are making tens of billions of dollars from these vaccines. A fourth issue is that after rich countries have reached the threshold to achieve herd immunity, international efforts to distribute the vaccine will significantly slow down. This was the pattern with HIV/AIDS; while a massive grassroots campaign of HIV-positive people and their allies was largely responsible for educating the public about HIV/AIDS and getting the medical community to address the epidemic, as the therapies became more effective at managing the symptoms, more privileged individuals and communities could live healthy and happy lives with the disease, while more impoverished communities were left behind. Today, the majority of HIV/AIDS cases occur in middle and low resource countries, and in rich nations, in poorer communities and communities of color. Some have described it as “a disease of inequality,” citing the strong correlation between HIV prevalence and income inequality, but it is just one on a long list. It is not unthinkable that a similar situation could develop with covid-19. Of course, covid-19 is much more easily transmissible than HIV, and the thought of permanently eradicating covid-19 in one or a few countries while the rest of the world continues to suffer is completely nonsensical. In our global economy, as we have seen, regional diseases can become worldwide pandemics within a matter of weeks, and just as soon as one region seems to have it under control, visiting neighbors from another region can set entire communities back. With new technologies being pioneered with the covid-19 vaccines, the rate of new vaccine development is expected to accelerate in the next few years -- perhaps fast enough to keep pace with even more dangerous covid-19 variants. But even that is a pipedream, considering how much the United States relies on overseas labor and goods. This present pandemic has revealed how extraordinarily unequal this country is; as essential workers making starvation-level wages have been forced to risk their lives, oftentimes without health insurance, the call for Medicare for All is more relevant, pressing, and louder than ever. As of this date, over 515,000 American lives have been lost to the pandemic -- many of them with comorbidities or other risk factors that are preventable given adequate healthcare. Even if we quickly get the pandemic under control, we as a society will be dealing with the long-term health consequences (and associated costs) for years. The establishment of universal single-payer healthcare in the United States is an actionable, equitable, and immediately beneficial goal for us as Americans. In the 1970s, a movement to create equitable accommodations and to remove social stigma for people with disabilities was often led by polio survivors; they are the reason we have ramps next to stairs, special parking for the handicapped, and other accessibility options that have improved our society. But this is a global pandemic, and we live in a global community. As we as a nation begin to recover from this catastrophe, let us not forget that full recovery can only occur after the pandemic has been defeated everywhere. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Challacombe, Stephen J. “Global Inequalities in HIV Infection.” Oral Diseases, vol. 26, no. S1, 30 Aug. 2020, pp. 16–21., doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13386. Fox, Margalit. “Hilary Koprowski, Who Developed First Live-Virus Polio Vaccine, Dies at 96.” The New York Times. 20 April 2013 (accessed 7 April 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/21/us/hilary-koprowski-developed-live-virus-polio-vaccine-dies-at-96.html Kollewe, Julia. “From Pfizer to Moderna: who’s making billions from Covid-19 vaccines?” The Guardian. 6 March 2021 (accessed 7 April 2021). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/mar/06/from-pfizer-to-moderna-whos-making-billions-from-covid-vaccines Noble, Greg. “From The Vault: Dr. Albert Sabin saved the world from polio.” WCPO Cincinnati. 29 July 2020 (accessed 7 April 2021). https://www.wcpo.com/news/our-community/from-the-vault/from-the-vault-dr-albert-sabin-saved-the-world-from-polio Seuss, Jeff. “Our history: Sabin and Salk competed for safest polio vaccine.” Cincinnati Enquirer. 10 May 2019 (accessed 7 April 2021). https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2019/05/10/our-history-albert-sabin-jonas-salk-competed-for-safest-polio-vaccine/1140590001/ “World Health Day 2021.” World Health Organization. (accessed 7 April 2021). https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-health-day/2021 Yesterday was Transgender Day of Visibility, an annual celebration of transgender, nonbinary, and other gender-variant persons and their contributions to society. While many usually highlight living transgender people on that day, the public still knows very little about historical gender-variance. Therefore, this week we will give tribute to a transgender American religious leader born in 1752 whose story of gender-nonconformity and prophethood gives much context to the Revolutionary Period of American history. It is a story about rejection, resurrection, and revolution: the story of the Public Universal Friend.

(A note about pronouns: contemporaries usually referred to the Public Universal Friend with masculine pronouns or avoided pronouns, opting to use “the Friend” or “P.U.F.” While the use of the pronouns “they/them” have been used informally to refer to singular persons for centuries, including in the time of Wilkinson/the Friend, it is only in recent years that the convention has begun to be formalized. For this piece, we will use feminine pronouns to refer to Jemima Wilkinson and modern gender-neutral pronouns for the Public Universal Friend, since followers considered the two to be distinct entities -- the former a woman, and the latter a genderless being.) Assigned female at birth, Jemima Wilkinson grew up in the Quaker religious community of Rhode Island during a time of passionate spiritual revival and experimentation. With the Quaker community in her area increasingly insular and concerned with membership purity, Wilkinson began to explore other spiritual traditions and trends. By her early 20s, Wilkinson was starting to attend services of the New Light Baptists, a new religious sect inspired by the Great Awakening spiritual movement. The New Light Baptists rebelled against traditional sources of authority, including old church hierarchies and civil authorities, instead emphasizing the primacy of the Bible and the cultivation of a personal relationship with God through the Holy Spirit. In principle, Quaker theology also highly regarded the individual relationship with God and the importance of every person’s “inner light,” but the vigorous energy and excitement around the New Light services stood in stark contrast to the somber and stilted atmosphere of Quaker services of the time. This spiritual exploration and other behaviors deemed unacceptable resulted in Wilkinson and some of her other family members from being expelled from the Quaker community in 1776. It was a tumultuous and uncertain time for the Thirteen Colonies. Colonists mostly in New England had been waging one rebellion after another against British authority for years: protests against the Sugar Act in 1764, the Stamp Act in 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767-1768, and of course, the Tea Act of 1773, which prompted the famous Boston Tea Party. In 1774, Parliament passed the so-called Intolerable Acts in order to discipline the colonists after the immense property destruction caused by the Boston Tea Party. Frustrations were boiling over, rebellion was in the air, and many colonists were starting to interrogate basic assumptions about people, society, and authority. The next year, colonists were already fighting battles against British soldiers in Massachusetts, and in 1776, the Declaration of Independence was made and a Continental Army formed. On October 5, 1776, Wilkinson fell severely ill with a sickness thought to have been brought to the area by the Continental Navy ship Columbus -- a fairly common occurrence in colonial Rhode Island. But while all others either eventually recovered or simply succumbed to disease, something peculiar seemed to happen to Jemima Wilkinson. After being bedridden and feverish for days, Wilkinson suddenly arose, apparently fully recovered, but proclaiming that the soul of Jemima Wilkinson had died and ascended to Heaven. In her place, God had allegedly instilled Wilkinson’s body with a divine spirit neither male nor female to be a holy servant: the Public Universal Friend. The Jemima Wilkinson name was abandoned, and the Public Universal Friend wasted no time in enacting their divine mission. Regardless of how we conceive of gender today, it is clear that the Friend was convinced of their own transformation. At no point for the rest of their life did the Friend deviate from the new persona, consistently defending their identity as a divine genderless entity. The Friend kept few personal possessions and no real fortune. They spoke in an ambiguously deep, sonorous voice. They adopted androgynous dress: men’s hats and unique neck kerchiefs somewhat similar to masculine trends of the time, but also long hair and long flowing garments of their own design, halfway between clerical robes and gender-neutral morning gowns. In a society in which gender and style of dress was an essential conveyer of social standing, the Public Universal Friend’s ambiguous appearance confounded many. The Public Universal Friend almost immediately began preaching, giving speaking tours around Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania to growing numbers of followers, many of whom had also been cast out by the Society of Friends (the official name for the Quakers). Much of the content of the Friend’s spiritual message was not too dissimilar from many other group’s beliefs. Unsurprisingly, the Friend borrowed much from Quaker theology, while also incorporating their charismatic leadership and millenarian apocalyptic prophecies drawn from the Great Awakening: a belief in free will over predestination, the equal value of all humans’ inner lights in the eyes of God, and an imminent apocalypse for which all must prepare. The result was a mix of doctrines familiar enough to both ex-Quakers and New Light adherents to attract a decent following of men and women, including some prominent members of society. But the Public Universal Friend also emphasized some of the more radical implications of these doctrines: the abolition of slavery and inclusion of Black followers at services, the rejection of traditional patriarchal authority, and universal hospitality regardless of faith or background. By 1790, the Friend and their followers, the Society of Universal Friends (not to be confused with the Society of Friends, a.k.a. Quakers) had bought land from the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), founded a settlement in western New York, and put the land in trust. In their new home, woman-leaders took charge and became particularly prominent in the community. During the tense post-war negotiations between the new United States government and the Haudenosaunee (who had largely sided with the British), the Friend was the only American non-man who attended and spoke during the talks. The Friend gave a sermon, translated by an interpreter, to both the American men and the Haudenosaunee men and women in attendance. Speaking about the importance of love and peace between peoples, the Friend impressed the Haudenosaunee, and may have been a major contributing factor for them to agree to the landmark Treaty of Canandaigua. Detractors had disrespectfully questioned and rejected the Public Universal Friend’s gender, unique dress, and spiritual sincerity from the moment the Friend announced themself. Others spread false rumors of violence and charlantry. Some of the confusion and suspicion has continued over the centuries, with one book as recently published as in 1964 rejecting the Friend’s nonbinary gender identity in the very title: Pioneer Prophetess. Modern gender conceptions are still in flux, and were far less developed in 1964, but then and now, gender is largely known and expressed through performance: how one dresses, speaks, and behaves. The Friend deliberately blended traditional masculine and feminine features in attire and mannerisms to forge a wholly unique gender identity that was inseparable from their identity as a divine prophet. Today, we can remember the Public Universal Friend as an early American example of a nonbinary transgender leader, well before those terms were invented. The Friend arose in the wake of a society-shaking religious movement, in the middle of an uncertain political revolution, and at the start of a massive war. Some even to this day have accused the Public Universal Friend of simply being a character Jemima Wilkinson invented to break from patriarchal notions of gendered work, which at the time excluded women from the pulpit. Wilkinson, these accusers claim, simply took advantage of the revolutionary spirit of the time that forced so many to question basic assumptions of their lives. But regardless of the Friend’s sincerity with regards to prophethood, the sincerity of their nonbinary gender seems genuine. The Public Universal Friend died on July 1, 1819, and was ultimately buried in an unmarked grave according to their wishes. Having been centered around a charismatic leader, the Society of Universal Friends dwindled and eventually fell into obscurity, although some descendants still live in the area today and still keep old stories, if not artifacts, from the time when the Friend was with them. May the tumultuous and historic times we are currently experiencing force us to question some of our society’s basic assumptions. May we see in our own time prophets of peace, love, and spiritual rebellion blend tradition with modern thinking to explore new ways of being and to reveal what is possible in the world. May we all be inspired by this truly unique figure who carved out a seemingly impossible existence through religious conviction and community-building. And let us recognize, through our own still-developing conceptions of gender that transgender, nonbinary, and gender-variant persons have always been here. -- Supporting Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Larson, Scott. “‘Indescribable Being’: Theological Performances of Genderlessness in the Society of the Publick Universal Friend, 1776-1819.” Early American Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, 2014, pp. 576–600. Beyond the Binaries: Critical Approaches to Sex and Gender in Early America (Fall 2014). Moyer, Paul B. The Public Universal Friend: Jemima Wilkinson and Religious Enthusiasm in Revolutionary America. Cornell University Press, 2015. Wisbey, Jr., Herbert A. Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend. Cornell University Press, 1964. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed