|

Which is scarier: a sudden death by inferno and collapsed buildings, or a slow death by lethal amounts of ubiquitous invisible radiation? Which is scarier: a single nuclear explosion in your community, or many nuclear explosions around your community?

In the 1950s, the US government determined that despite the presence of the US Submarine Base and General Dynamics: Electric Boat in the New London - Groton area, southeastern Connecticut would not be a major military target in the event of nuclear war. The area, however, is surrounded by several likely major targets. How would nuclear attacks in the region around southeastern Connecticut affect our corner of the state? In 1960, Professor Gordon S. Christiansen, chairman of the Connecticut College Chemistry Department at the time, gave a description of such a hypothetical horror in his pamphlet Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Over the past few months, we have slowly doled out the contents of the pamphlet in excerpts. Excerpts 1 & 2 regarded the effects of a Hiroshima-size atomic bomb detonated over the New London - Groton bridge: the initial blast, firestorms, and radiation. Parts 3, 4, & 5 explore the same scenario but with a much more powerful “modern” thermonuclear weapon. (Read Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2029219227228402) (Read Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2040482629435395) (Read Part 3 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2046153552201636) (Read Part 4 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2057147997768858) (Read Part 5 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2062709130546078) (Read Part 6 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2085738148243176) The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ famous Doomsday Clock was set at “100 seconds to midnight” in both 2020 and 2021. At no other moment in history since the Doomsday Clock began have we come so close to utter calamity as we are now. Even while covid continues to ravage many parts of the world, nuclear programs in multiple countries have recently accelerated while other efforts to control nuclear arms internationally have eroded. The result is a highly destabilized world with even more nuclear weapons, nuclear states, and possible reasons to use such weapons than even in Professor Christiansen’s day in the Cold War. Therefore, earlier this year, the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force, which made nuclear weapons illegal under international law. While there is still much work to do to convince the nuclear states to give up those arms, there is also reason to believe that this new treaty is the beginning of a new chapter in responsible international control of nuclear arms. — To complete the dismal prospect it is necessary to point out the difficulty of recreating a normal existence even after six months of imprisonment in a shelter. During the second half of the first year the average level of fallout radioactivity would be about 0.7 roentgens per hour, a level that makes human occupancy impossible. A person exposed to this radiation for six months would receive 3000 roentgens, probably a fatal dose even spread over so long a time. During the fifth year after the disaster, when levels of radioactivity would be slowly decaying from 0.1 roentgens per hour, a person who is constantly exposed would get a dose of something over 800 roentgens per year — a fatal injury in a single short dose but perhaps only a third of the fatal dose when taken slowly. The possibility of recreating this highly organized, industrial and partially urbanized community could only remain a dream of the future. Even the chance of a general rural farming community is slim. Undoubtedly natural changes in surface features of the land, greatly hastened by the excessive erosion of a denuded landscape, would cause great redistribution of the radioactive material. There would be some areas which would be naturally decontaminated by this process; there would also be other areas where the concentration of radioactivity would build up. It is quite probable that spotty areas would be reclaimed for farming, but it would be necessary to constantly and carefully check the produce of these farms for dangerous concentrations of radioactivity. It is well known that many plants and animals have a great tendency to concentrate some radioactive materials such as strontium 90 to levels far above their concentration in the soil. A safe and relatively unirradiated life in this area, even five years after the bombing, would depend first on a good working knowledge of the nature of radioactivity, its biological effects, its fallout origins, and its physical properties; it would also require considerable elegant radiological measuring equipment; it would also require a remarkable level of awareness, vigilance and restraint. The likelihood of help coming from outside this area is almost nonexistent. All ordinary means of communication and transportation would be totally destroyed. After several weeks or a few months it would be possible for an airplane or a boat to come here briefly (if facilities to receive them could be improvised). But one is always faced with the question, “Where would help come from? What could be brought here that is not needed just as badly elsewhere?” The probability is very great that conditions would be just as terrible throughout the whole eastern seaboard area, at least as far away as Washington, D.C. The more remote areas of the South and West, though probably not hit as badly as New England, would have fantastically difficult problems of their own. They would surely have more survivors — but would also have many more sick, injured and starving to care for. More probable than the arrival of teams of saviors would be the arrival of roving bands of marauders — frightened, injured, maddened, short-term survivors of other similarly devastated areas. If a person should be so lucky and so foresighted to have prepared and occupied in advance a perfect shelter stocked with the necessities of life underground, he might have to defend it against the raids of others who were not so lucky or so thoughtful in advance. He might even find it not worth defending. Could we survive a nuclear attack? Can shelters save us? Is there any defense? Is there anything we can do now to prevent this tragedy? The one clear and effective thing we can do is to strive to ensure that these hypothetical incidents do not become actual ones. — Take Action If you are concerned about nuclear weapons and live in Connecticut, consider joining the CT Committee on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Committee organizes demonstrations against nuclear weapons throughout the year. Sign up to the mailing list here: https://forms.gle/pX8v2U4CktAcz8s78 You can also sign petitions to pressure our government to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, like this one: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/support-the-nuclear-weapons-ban-treaty — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Christiansen, Gordon S. Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Connecticut College, 1961. — Further Resources “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat Mecklin, John, ed. “2021 Doomsday Clock Statement.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 27 January 2021 [Accessed 20 October 2021]. https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/ “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ Which is scarier: a sudden death by inferno and collapsed buildings, or a slow death by lethal amounts of ubiquitous invisible radiation? Which is scarier: a single nuclear explosion in your community, or many nuclear explosions around your community?

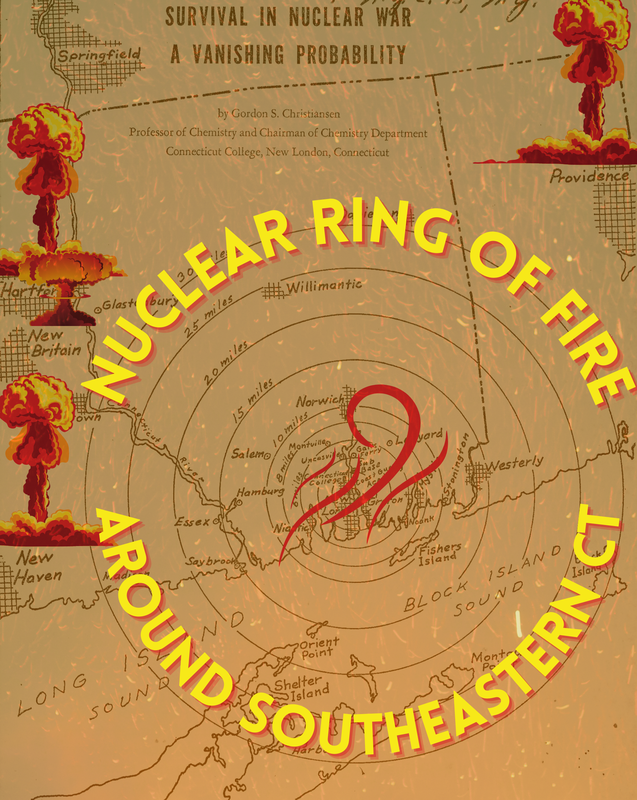

In the 1950s, the US government determined that despite the presence of the US Submarine Base and General Dynamics: Electric Boat in the New London - Groton area, southeastern Connecticut would not be a major military target in the event of nuclear war. The area, however, is surrounded by several likely major targets. How would nuclear attacks in the region around southeastern Connecticut affect our corner of the state? In 1960, Professor Gordon S. Christiansen, chairman of the Connecticut College Chemistry Department at the time, gave a description of such a hypothetical horror in his pamphlet Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Over the past few months, we have slowly doled out the contents of the pamphlet in excerpts. Excerpts 1 & 2 regarded the effects of a Hiroshima-size atomic bomb detonated over the New London - Groton bridge: the initial blast, firestorms, and radiation. Parts 3, 4, & 5 explore the same scenario but with a much more powerful “modern” thermonuclear weapon. (Read Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2029219227228402) (Read Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2040482629435395) (Read Part 3 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2046153552201636) (Read Part 4 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2057147997768858) (Read Part 5 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2062709130546078) The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ famous Doomsday Clock was set at “100 seconds to midnight” in both 2020 and 2021. At no other moment in history since the Doomsday Clock began have we come so close to utter calamity as we are now. Even while covid continues to ravage many parts of the world, nuclear programs in multiple countries have recently accelerated while other efforts to control nuclear arms internationally have eroded. The result is a highly destabilized world with even more nuclear weapons, nuclear states, and possible reasons to use such weapons than even in Professor Christiansen’s day in the Cold War. Therefore, earlier this year, the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force, which made nuclear weapons illegal under international law. While there is still much work to do to convince the nuclear states to give up those arms, there is also reason to believe that this new treaty is the beginning of a new chapter in responsible international control of nuclear arms. — The third hypothetical situation which should be examined is that in which no bombs are detonated in Southeastern Connecticut but some reasonably probable level of nuclear attack is suffered by the New York - New England area. In the 1959 Joint Congressional Committee estimates seventy metropolitan areas in the United States were assumed to have been hit by a total of 550 megatons explosive equivalent. This is a truly mild attack in view of the known Russian capabilities which include at least 40,000 megatons of nuclear weapons and adequate means (aircraft and missiles) to deliver most of them. Furthermore, the sizes of weapons tended on the small side of what might be reasonably expected. Ten megaton weapons were the largest considered in this hypothetical study and most were in the one to three megaton size — in spite of the fact that the standard big nuclear weapons, easily carried even by medium bombers, are the 20 megaton size. In the Congressional estimates it was assumed that New York and Boston would each be hit by two 10 megaton bombs; Providence by one 10 megaton; Albany by an 8 megaton; Hartford and Springfield by a 3 and 2 megaton each; Bridgeport, New Haven and Worcester by one 3 megaton each; and New Britain and Waterbury by a one megaton each. Thus, within a 100 mile radius of Southeastern Connecticut about 80 megatons of nuclear explosive would be detonated in a minimal attack. The distances of even the closest bursts are such that our community might escape the major blast and fire damage. The remaining major effect, radiation, would come from the local fallout. If there were a strong and persistent wind from the straight south, we would escape the worst of the fallout; if the wind were from any other direction, we would be in an area of fallout more intense than any except in the immediate vicinity of nuclear explosions. The prevailing south westerly wind would put us in the direct path of the fallout from the highest concentration of bombs in the nation. Consideration of the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory estimates of an average level of radiation of 7500 roentgens per hour makes it reasonable to assume a level of twice this, 15,000 roentgens per hour, near this heavily bombed area. This would be the level of fallout radiation at the end of the first hour after detonation, about the time heavy fallout would reach this area. Under these conditions unprotected exposure for five minutes would be a certainly lethal dose of radiation. To examine the effects of this radiation it is simplest to make a timetable of how much radiation a person in the open would likely to receive and then consider various types of protective measures he might take. If one takes the above assumptions: (a) that serious fallout reaches this area the first hour after detonation and (b) a level of 15,000 roentgens have dropped to about 1 roentgen per hour; in four years it would be about 0.1 roentgen per hour. The head of a household would probably be willing to risk exposure to radiation by leaving the shelter as much as an hour a week after the first two weeks of extremely intense fallout radiation. On such a schedule he would receive a total of about 150 roentgens in six months time. This would include the 75 roentgens he would receive during the major part of his time which he spends inside the shelter; the other 75 roentgens would have been his hour a week dose of direct radiation in the open. Half of this dose would have been the expense of his first four excursions out of the shelter, while an hour spent in the open six months after bomb day would cost him only about 1 roentgen. A person could avoid death by radiation on such a schedule but it is questionable whether he could avoid death by starvation or disease. And it is perfectly clear that no semblance of community life or function could be recreated. If the survivor could manage to avoid any exposure during the first month, then he could double his time above ground during subsequent months and still get the same exposure of 150 roentgens. But two hours a week could hardly be considered active community participation… — Take Action If you are concerned about nuclear weapons and live in Connecticut, consider joining the CT Committee on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Committee organizes demonstrations against nuclear weapons throughout the year. Sign up to the mailing list here: https://forms.gle/pX8v2U4CktAcz8s78 You can also sign petitions to pressure our government to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, like this one: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/support-the-nuclear-weapons-ban-treaty — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Christiansen, Gordon S. Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Connecticut College, 1961. — Further Resources “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat Mecklin, John, ed. “2021 Doomsday Clock Statement.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 27 January 2021 [Accessed 20 October 2021]. https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/ “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ Here at the end of Latinx Heritage Month, we are wrapping up our series on Puerto Rico by highlighting Jason Ortiz, a Connecticut Puerto Rican activist-organizer probably best known for his work in cannabis justice in our state: he’s the current executive director at Students for Sensible Drug Policy, the policy director for Connecticut United for Reform and Equity (CURECT), and founder and immediate past president of the Minority Cannabis Business Association. But Ortiz’s activist work has had a long arc. He was first trained in nonviolent direct action by VPT Board President Joanne Sheehan and had his political awakening as a teen when he participated in a protest at the infamous School of the Americas in Georgia with a YouthPeace organizer. But aside from cannabis activism, Jason Ortiz perhaps performed his most impactful work as the founder and president of CT Puerto Rican Agenda. It was through this organization that Ortiz was able to organize relief efforts and emergency lodgings in Connecticut for thousands of displaced Puerto Ricans after Hurricane Maria.

A few weeks ago, we got to interview Jason Ortiz about Connecticut Puerto Ricans, challenges and advantages in organizing along ethnic lines, and advice for organizers in those positions. We have included parts of that interview below. [Read The Recolonization of Puerto Rico, Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2012501098900215] [Read The Recolonization of Puerto Rico, Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2068347923315532] [Read The Recolonization of Puerto Rico, Part 3 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2073703802779944] When Hurricane Maria reached Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, the island was still recovering from its brush with Hurricane Irma just a couple of weeks earlier. The power grid had failed for about two-thirds of the island, another third had lost access to clean water, and various infrastructure elements were badly damaged. When Maria developed into a Category 4 storm and slammed into the already battered island, it knocked out the rest of the power grid and 95% of cell towers, majorly flooded thirty rivers, destroyed nearly all road signs and traffic lights, structurally damaged an unknown number of buildings, and closed over 90% of roads even a month after the hurricane had passed. The wide dispersal of Puerto Ricans through much of the United States has at times strengthened the home island. Puerto Ricans make up over 8% of the Connecticut population, the highest percentage of any US state. Puerto Ricans in Connecticut generally maintained close ties with family and friends on the home island, then and now, and many Puerto Ricans still frequently travel between the island and the US mainland. Thus, various issues and crises in Puerto Rico over the decades have often felt much closer to Connecticut than the geographical distance would suggest. Therefore, even before Maria ripped through the island, some Puerto Ricans in Connecticut were already preparing relief efforts for the aftermath of Irma. In June 2017, a group of Puerto Rican politicians, community leaders, and activists across the state founded CT Puerto Rican Agenda, a chapter of National Puerto Rican Agenda. Jason Ortiz became the first president of the Connecticut chapter and quickly joined the CT PR Agenda to the national Puerto Rico Hurricane Relief Network. Even considering past pan-Puerto Rican campaigns like the anti-Navy work on Culebra and Vieques islands, the scale of the effort for Hurricane Maria relief was “unprecedented” in the Puerto Rican diaspora. In the early stages, according to Ortiz, “the folks stateside were mobilizing faster than the needs on the island, and I think that does show… that that network [connecting Puerto Rico and the mainland US] is stronger than it ever has been before.” Despite the strong Puerto Rican network, there were still challenges to organizing around such a multifaceted and catastrophic issue as hurricane relief. For Jason Ortiz, part of the challenge was trying to balance the needs of hurricane-displaced Puerto Ricans and the needs of local vulnerable populations: “The work with the families was so hard, they needed things like housing and jobs which Hartford residents didn’t even have. For example, we had to ask for the displaced families to be put at the front of the affordable housing line, which meant Hartford families who were already waiting had to wait longer.” But organizing Puerto Rican communities statewide also meant that the coalition could draw from more resources. According to Ortiz, “The Center for Latino Progress played a big role. The San Juan Center and the Puerto Rican Day Parade of Hartford helped as well. Joe Rodriguez from Blumenthal’s office played a big role getting us spaces and donors. But mostly it was Puerto Ricans who were not in an official group. Through the hurricane efforts people kind of knew each other, but it felt like one of the few times we organized Ricans statewide — Hartford Ricans were meeting the Meriden Ricans, who finally met the Bridgeport Ricans, etc. outside of the establishment Ricans.” Many of the Puerto Ricans within these cities already had strong relationships with each other through extended family ties, churches, and various cultural activities. Jason Ortiz, the CT PR Agenda, and the rest of the statewide coalition were able to unite these pre-existing relationships and communities into a single cause. These unification efforts bore fruit. The Connecticut National Guard flew emergency supplies into Puerto Rico and St. Thomas. In the state itself, Connecticut acquired the temporary housing of roughly 13,500 displaced Puerto Ricans — 10% of all Puerto Ricans who left the island for shelter on the mainland. At the peak, 187 families were housed in hotels like the Red Roof Inn in Hartford through the FEMA Transitional Sheltering Assistance program. The coalition in Connecticut initially received $3 million in state funds to support displaced families, and in conjunction with state leaders like Senator Blumenthal and former Governor Malloy, successfully had the funding renewed multiple times. And all this was accomplished in the face of a president who was intentionally slow to respond to the crisis and who was at the time actively stoking white supremacy. Many of the intercity relationships between Puerto Rican communities in Connecticut that were forged during the Hurricane Maria crisis have continued to develop, although not necessarily through formal channels. While Jason Ortiz left CT PR Agenda to focus on cannabis justice in Connecticut, he has since been able to draw on some of these relationships he had helped to develop. Some had joined in the minority cannabis justice movement that successfully convinced the Connecticut State Legislature to decriminalize cannabis this year. Although CT PR Agenda is now defunct, Ortiz holds high hopes for the political potential of these communities. With the growing Puerto Rican population in Connecticut, as well as climate change exacerbating hurricanes in the Caribbean, the need for broad organizing will likely increase in the coming years. For the organizers who find themselves in these kinds of communities, Ortiz has some advice: “Don’t try to get everyone to do the same thing. Give folks lots of autonomy but then support. And trainings are a must, and on a continuing basis. It’s ok to start small and let folks develop relationships before, say, organizing a statewide march or something. Organizing around ethnic lines by definition requires it to be across ideological lines, so it will be necessary to put aside political purity to get to real unity, but simultaneously allowing for the views to be expressed even if you disagree with the content. It’s less about finding one path and more about finding lots of different ways.” -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources dos Santos, Cyrus. “Puerto Rico Struggles With Recovery, Connecticut Officials Promise Help.” CT News Junkie. 22 September 2017 [Accessed 12 October 2021]. https://ctnewsjunkie.com/2017/09/22/puerto_rico_struggles_with_recovery_connecticut_officials_promise_help/ “Housing Benefits Extension to Puerto Rican Families Halted.” NBC Connecticut. Last updated 19 January 2018 [Accessed 12 October 2021]. https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/housing-benefits-extension-to-puerto-rican-families-halted/141604/ Ormseth, Matthew. “Hurricane Maria, One Year Later: Exodus Strained Connecticut, But Families And Service Providers Still Resilient.” Hartford Courant. 20 September 2018 [Accessed 12 October 2021]. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-news-hurricane-maria-year-later-20180918-story.html Park, Daz. “Interview with Jason Ortiz on CT-PR Activist Organizing.” 14 Sept. 2021. Ragland, Jamil. “Ortiz: Puerto Rico facing long, challenging recovery — bravely.” The CT Mirror. 29 October 2017 [Accessed 12 October 2021]. https://ctmirror.org/2017/10/29/ortiz-puerto-rico-facing-long-challenging-recovery-bravely/ Scott, Michon. “Hurricane Maria’s devastation of Puerto Rico.” Climate.gov. Last updated 18 April 2021 [Accessed 12 October 2021]. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/hurricane-marias-devastation-puerto-rico Last week, we told the story of the popular nonviolent resistance of the early 1970s that ousted the US Navy from the Puerto Rican island Culebra. For decades, two-thirds of Culebra had been controlled by the US Navy which used the island for combat training and weapons testing, including a bombing range. Although the campaign was ultimately successful in forcing the US Navy out of Culebra, the US military simply moved their Culebra operations to the other Puerto Rican island they controlled: Vieques. But when an errant ordnance during a botched bombing run exploded and killed Viequense civilian worker David Sanes on April 19, 1999, a new campaign to remove the US Navy from Vieques was born.

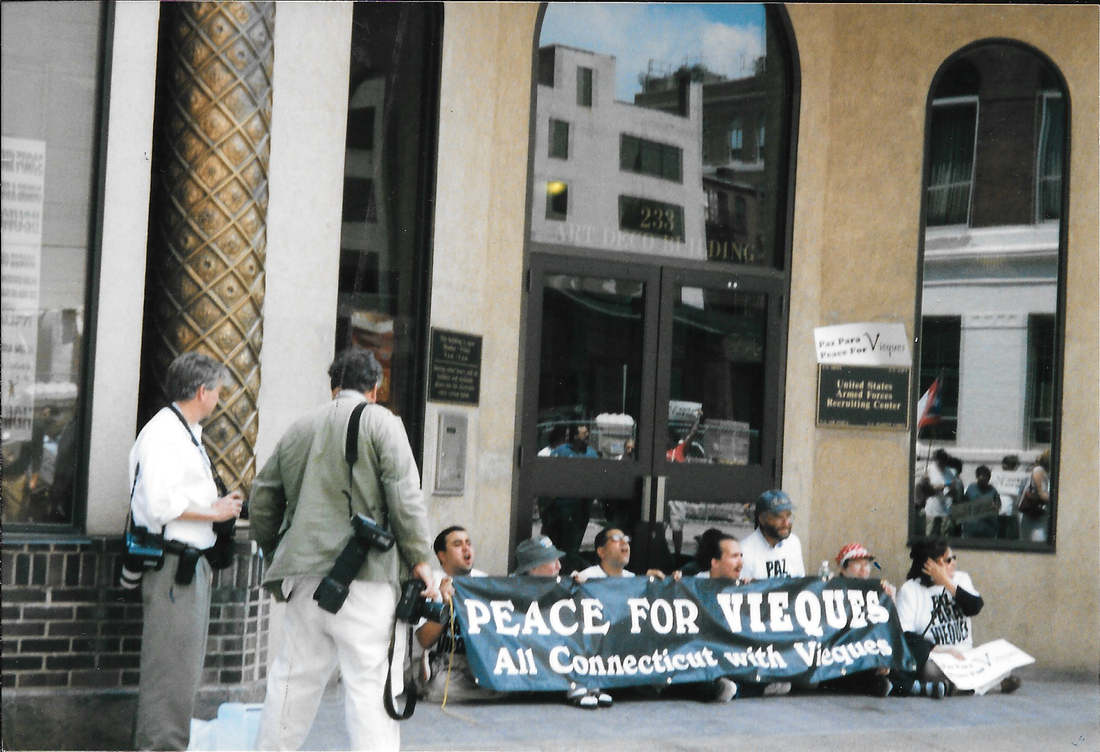

[Read The Recolonization of Puerto Rico, Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2012501098900215] [Read The Recolonization of Puerto Rico, Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2068347923315532] Protests against the US Navy presence in Vieques had been going on for decades — in fact, the New England Community for Nonviolent Action (CNVA; founders of the original VPT) had helped to organize a demonstration on the very matter as early as October 1978 at the Naval Submarine Base in Groton. They sought to end the decades-long occupation of their island by the US Navy which had harmed local fisheries and wildlife, disrupted civilian infrastructure and daily life, severely worsened the health of Vieques residents, and taken over three-quarters of the island. Additionally, the Viequenses demanded that the US clean up more than half a century’s worth of unexploded ordnance, industrial chemicals, and heavy metals including depleted uranium with which they had polluted the island and surrounding waters. In 1993, some of the local anti-Navy efforts from civic and community leaders in Vieques coalesced into the Committee for the Rescue and Development of Vieques (Comite por Rescate y Desarrollo de Vieques, CPRDV). Soon, the coalition expanded to include Vieques fishers, women’s and youth organizations, religious leaders, and other groups on the small island. On the night of Sane’s death, 200 residents of Vieques protested at the entrance of the US Navy’s Camp García. The number of protesters rose to 300 the next day, and the movement grew quickly from there. The Association of Fishermen in Vieques staged their own protest by laying wreaths and an eight-foot cross where Sanes was killed. Civil disobedience encampments appeared on the US Navy training grounds across Vieques, organized by various groups: a pan-denominational Christian coalition, the teacher’s federation, university students, political parties, and others. Trainers from the American Friends Service Committee, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and the War Resisters League held civil disobedience and nonviolent action workshops in the encampments. And as the protests grew, people began to connect the US military’s exploitation of Vieques as training and bombing grounds with the country’s controversial involvement in the Kosovo War and the military-industrial complex as a whole. Soon, the protesters successfully pressured some Puerto Rican government officials to make an official request to President Clinton to immediately cease military operations in Vieques. But despite the popular movement and the sympathies of some officials, Puerto Rican Governor Pedro Rosello refused to intervene on the protesters’ behalf. Many activists publications, including The Nonviolent Activist, shared solidarity and support requests widely: “The people of Vieques are asking mainland U.S. activists for support, specifically for environmental, ecumenical, peace and trade union organizations and individuals to bring up the issue of Vieques at the workplace, in schools, at community and religious meetings and to join the demand for the demilitarization of Vieques, a paradise invaded.” As mentioned last week, Connecticut has the highest percentage of Puerto Ricans among the fifty states. So, it is no wonder that when the Committee for the Rescue and Development of Vieques (Comite pro Rescate y Desarrollo de Vieques, CPRDV) began to organize a resistance campaign after Sanes’ death, many Puerto Ricans and non-Puerto Ricans from Connecticut joined. In Hartford, one group held demonstrations outside of the Puerto Rican Federal Affairs Office in solidarity with the people of Vieques and CPRDV to pressure Governor Rosello to side with the Puerto Rican people against US colonial exploitation. In February 2000, a demonstration with 150,000 protesters was held in San Juan. A couple of weeks later, Puerto Rican activists and teen members of the Norwich Free Academy YouthPeace Club (which held weekend workshops at VPT) demonstrated outside of the Navy Base in Groton. On May 4, 2000, US marshals and about 1000 Marines attempted to break up the encampments on Vieques only to find hundreds of CPRDV allies from around the world descend upon the restricted zones just five days later. That summer, the YouthPeace Club traveled up to Hartford to join the local Puerto Rican group All Connecticut with Vieques and their allies in solidarity. The US Navy and federal government attempted to negotiate with the CPRDV, offering $90 million in exchange for the continued use of part of the island as a live-munitions training zone. But CPRDV had unequivocally articulated their demand for the unilateral evacuation of the US Navy from Vieques within just a few months of Sanes’ death. Finally, in July 2001, over two years after the Sanes’ death, a nonbinding referendum was held on Vieques: 68% voted for the US Navy’s immediate removal, while 30% voted to accept the money in exchange for indefinite US Navy presence. Between the massive civil disobedience disruptions, the expenses related to property damage (mostly to barriers like fences), and now this very large and clear majority of Vieques residents and solidarity groups on the mainland maintaining their hard line after two years,(ADD) the US Navy and federal government had had enough. Reversing President Clinton’s decision to continue negotiations with the people of Vieques, President Bush declared that all military exercises in Vieques would cease by February, and that the US Navy would be evacuated from the island by May 2003. The federal government followed the agreement, but also established wildlife preserves on much of the land formerly used by the US Navy as waste dumping grounds and other heavily polluted areas. Some have argued that the redesignation of those lands freed the federal government from taking responsibility for cleaning up the pollution it had dumped there for decades. The fact remains that on both Culebra and Vieques, the vast majority of unexploded bombs and toxic waste has not been removed, and a recent federal report states that cleanup efforts will not be completed until at least 2032. Still, despite the challenges that remain, within just over three decades, the people of Puerto Rico and their allies successfully ousted the US Navy from not one but two of the islands using civil disobedience and nonviolent action. The VPT community is proud to have participated in the efforts to decolonize Puerto Rico and to bring peace to the islands. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Colón Cortés, Wanda. “How a People’s Movement Stopped the Bombing in Vieques.” Fellowship of Reconciliation. January 2007 [Accessed 5 October 2021]. https://www.proquest.com/openview/30aac6b5c1cbbdb811bd93bc212ef22b/1?cbl=2041863&pq-origsite=gscholar “Puerto Ricans force United States Navy out of Vieques Island, 1999-2003.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. [Accessed 5 October 2021]. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/puerto-ricans-force-united-states-navy-out-vieques-island-1999-2003 “Puerto Rico cleanup by U.S. military will take more than a decade.” NBC News. 26 March 2021 [Accessed 5 October 2021]. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-cleanup-us-military-will-take-decade-rcna529 Rabin Seigel, Robert L. “The U.S. Navy Bombs Puerto Rico: Paradise Invaded.” Nonviolent Activist. July-August 1999. Richards, Ron. “U.S. Naval Bombing `Accident' In Vieques, Puerto Rico, Kills Resident.” The Militant. 3 May 1999 [Accessed 5 October 2021]. https://www.themilitant.com/1999/6317/6317_4.html “The Vieques Referendum.” The Hartford Courant. 2 August 2001 [Accessed 5 October 2021]. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-2001-08-02-0108021821-story.html |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed