|

One hundred and ten years ago today, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City caught fire, causing the deaths of 146 workers locked inside. Most of the 123 women and 23 men were recent Italian and Jewish immigrants in their teens and twenties: the oldest victim was 43-year old Providenza Panno, while the youngest victims were 14-year olds Kate Leone and Rosaria “Sara” Maltese. Most of the victims succumbed to fire or smoke inhalation inside the building, their deaths as invisible to bystanders outside as their daily toils had been in life. But witnesses also watched helplessly as 62 of the victims jumped or fell to their deaths from the 9th floor of the burning building. One of the deadliest and most infamous workplace disasters in American history, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire sent a deep shock through New York and the country as a whole, marking a turning point for the labor movement. The political establishment in New York awakened to the social crisis of immigrant labor abuse, a flurry of progressive legislation was passed, and the owners of the Triangle Waist Company, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, were disgraced. A closer examination of the details, however, reveals the broader societal reasons for the disaster which have largely persisted and continues to endanger, maim, and kill poor workers in the United States and around the world today.

The fire likely started from a lit cigarette tossed into a fabric scrap bin by a male worker or supervisor, as few women smoked at the time, but the fire jumped quickly through the cotton dust to the heaps of lightweight fabric all around the factory. Soon, the entire floor was roaring in flames -- the buckets of water hanging from the walls not nearly enough to slow the spread -- and workers attempted to flee. The floor only had two narrow staircases: within minutes, one was completely blocked by flames, while the other was found to be locked from the outside. Locking the doors of a factory was common practice at the time to prevent workers from taking unauthorized breaks or from stealing material from the company. The elevator operators for the two elevators servicing the 9th floor, Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillaro, both valiantly saved many workers’ lives by continuing to take people down from the burning level until the elevators failed. About 20 workers crammed themselves onto a fire escape, only for the poorly installed emergency escape to collapse and drop the workers to their deaths. Most of the remaining people trapped on the factory floor asphyxiated and burned. But at least a few dozen more chose to leap 100 feet to their deaths instead of die by fire. Louis Waldman, a New York Socialist state assemblyman and witness to the tragedy, years later wrote of the night: “Horrified and helpless, the crowds -- I among them -- looked up at the burning building, saw girl after girl appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, and then leap to the pavement below, to land as mangled, bloody pulp. This went on for what seemed a ghastly eternity. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street. Life nets held by the firemen were torn by the impact of the falling bodies.” At the time, the factory was considered state-of-the-art, with modern, well-maintained equipment, and the 10-year old building itself was designed to be fireproof -- indeed, the building was still structurally sound after the fire was put out. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was for a time held up as the model factory, head and shoulders above the typical sweatshop of the time. But there were no laws at the time mandating an anti-fire sprinkler system in factories, building codes were outdated for taller buildings and were rarely enforced anyway, the workers compensation law that was passed two years prior was ruled unconstitutional the day before the fire, and both government and law enforcement had largely sided with factory owners in labor disputes for decades. With a seemingly endless number of work-seeking immigrants in New York ready to be exploited, Harris and Blanck, like most factory owners of the time, had little incentive to care for the safety of their workers. A week after the fire, socialist union activist Rose Schneiderman, who helped lead a strike for waistshirt workers two years earlier in the Uprising of the 20,000, gave an impassioned public speech about the victims in which she argued that only worker solidarity could bring about positive change for workers: “I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting… The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.” Others in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and in the broader community turned to the government for greater workers’ protections. Frances Perkins, who later went on to be the first woman to serve in a US Cabinet and who had a large part in shaping the New Deal, headed a new Committee on Public Safety in New York City in the wake of the fire. Having witnessed the fire firsthand, Perkins would dedicate the rest of her life to labor reform. The work done by Perkins and her committee convinced the New York political establishment to take immigrant labor issues seriously, and led to the New York State Legislature forming their own Factory Investigating Commission. In just a couple years, the State’s Commission conducted interviews and investigations in hundreds of factories to determine how common dangerous working conditions were and what regulations were required to keep workers safe. Blanck and Harris were indicted on first- and second-degree manslaughter charges, but avoided conviction. During the trial, in a disturbing echo of modern conspiracy theories around “crisis actors” giving false testimony about mass shootings, eyewitness and survivor Kate Alterman’s testimony was scrutinized, and the defense attorney convinced the court that she had likely been coached to slander Blanck and Harris. Just two years later, Blanck was caught locking workers inside a factory again. He was fined the minimum amount: $20. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire was one of those moments in history that suddenly gripped the country and convinced huge swaths of the public that radical change was necessary: like the Boston Massacre in 1770, Bleeding Kansas and John Brown’s Raid in the 1850s, the Haymarket Massacre in Chicago in 1886, and the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis just last year. After each of these violent tragedies, after witnessing or hearing accounts from eyewitnesses, people all over were inspired to cause change, and a bevy of social movements working for reforms and solutions rose up. But 110 years after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, sweatshops still produce the majority of our clothes, underclass workers still toil in dangerous and restrictive jobs, and immigrants still struggle for basic rights. What’s worse, the labor movement that made such gains for working people in the first half of the 20th century has been gutted by the last few decades of deregulation and concerted anti-union rhetoric from some politicians. In the past decade, union organizers have allied with workers who don’t have unions for the Fight for $15 campaign. Starting with smaller campaigns at the local and state level in 2012, the Fight for $15 is now a national issue. This effort continues to expose not only the ubiquity of jobs that pay below a living wage, but also all the attending hardships that lead to shorter lifespans and unnecessary suffering. The covid-19 pandemic has thrown the inequity into an even starker light: consider “essential workers” in the last year being denied hazard pay and forced to risk their lives during a deadly global pandemic. The cause of improving conditions for working people intersects in multiple ways with women’s issues, immigration issues, the everyday difficulties of poverty, and so much more. We must not wait for the next tragedy to act; the tragedy has been happening all around us. Support workers’ struggles for better pay and working conditions. Participate in strikes, disruptions, boycotts, and other collective actions to force corporations and politicians to provide workers with necessary benefits, a living wage, and human dignity. -- Supporting Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources: Blakemore, Erin. “How a tragedy transformed protections for American workers.” National Geographic. 25 March 2020 (accessed 25 March 2021). https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire-transformed-protections-american-workers Liebhold, Peter. “Why the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Makes for a Complicated History.” Smithsonian Magazine. 17 December 2018 (accessed 25 March 2021). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire-makes-complicated-history-180971019/ “The Fire that Sparked the Labor Movement.” AFGE. 23 March 2018 (accessed 24 March 2021). https://www.afge.org/article/it-took-1-fire-and-146-dead-workers-to-change-workplace-safety-laws/ “Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.” AFL-CIO. (accessed 24 March 2021). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire-makes-complicated-history-180971019/ On Tuesday evening of this week, a young white man shot and murdered 8 people in three different spas around Atlanta, Georgia; 6 of the victims were Asian-American women. Over the summer last year, many Asian-American rights groups joined Black lives groups to call for justice in George Floyd’s murder. In the wake of Tuesday evening’s seemingly targeted murder spree (the shooter has denied a racial motivation), many groups that have organized around Black lives have since likewise made statements in solidarity with Asian-Americans against racist violence. This kind of interracial solidarity is not new, and in recognition of the little-known Asian-American contributions to civil right and other social justice movements, this Women’s History Month let us spread the stories of three Asian-American women who dedicated their lives to fighting injustice.

Grace Lee Boggs Grace Lee Boggs was a philosopher, civil rights leader, and leftist revolutionary who contributed immensely to both the theoretical and practical aspects of social change. Born to Chinese immigrants in 1915 in Providence, Rhode Island, Boggs eventually moved to Chicago and became involved in the tenants’ rights movement and the workers’ movement. Through that work, she became involved in the historic 1941 March on Washington, which was primarily organized by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin and which was a major influence on Dr. King’s 1963 March on Washington. In Chicago, Grace met African-American activist-organizer and auto worker James Boggs. In 1953, Grace and James married and moved to Detroit, where they continued their work on northern Black civil rights by helping to organize coalitions of communities to protect workers and women, to decrease street violence, and to resist the economic and police assaults on Black Detroiters. In 1992, Grace and James founded Detroit Summer, a summer program for volunteer youth from across the country to help revitalize neighborhoods in the city. A staunch leftist revolutionary, Grace Lee Boggs constantly challenged her own thinking, always growing in her understanding of injustice and the ways to resist it. Early on, she was heavily influenced by the German philosophers Kant and Hegel, and later by the Black revolutionary and her contemporary, Malcolm X. Later, Boggs became convinced of Dr. King’s revolutionary nonviolence and his insistence on the cultivation of the “beloved community” as a necessary and practical part of a successful political revolution. Having immersed herself in the Black civil rights movement for most of her life, Grace became a role model and a symbol of interracial solidarity for a new generation of Asian-Americans inspired by Black civil rights and disturbed by US aggression in Southeast Asia in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Deeply influenced by the growing Black Panther Party and the Asian liberation movements, in 1970, she and James along with other Asian-American activists in Detroit founded the Detroit Asian Political Alliance. Later that year, in a speech Grace gave to the Alliance, she said: “We are the first generation of Asian-Americans who are resisting assimilation… We have this choice today only because… the American Establishment… began opening up all sorts of doors to Chinese and Japanese. Now… we are repelled by the United States way of life. The Vietnam war has given us a glimpse into its biocidal and genocidal character. The Black revolt has given us an idea of the dehumanizing principles by which it operates.” But, it was not until after the death of her husband James in 1993 that Grace Lee Boggs deeply examined her Asian-American identity. In the last couple decades of her life, Boggs continued writing, working for her community, and evolving in her thinking. Her autobiography Living for Change was published in 1998, and her last book The Next American REvolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century was published in 2011. Grace Lee Boggs passed away on October 5, 2015 at the age of 100. Marion Kwan Marion Kwan was a dedicated Chinese-American member of the Black civil rights movement. In 1965, after attending a lecture at Hastings College about racial discrimination and violence against Blacks in the South, Kwan moved to Mississippi to work with the Delta Ministry. Through that group, Kwan became acquainted with many of the major civil rights groups of the time, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Kwan immediately recognized the physical segregation of African-Americans from whites in the South as similar to the zoning laws that kept Chinese people contained within “Chinatown” in San Francisco, but also knew that the situation was significantly more dire for African-Americans. In her own words: “It was there, all right; systemic racism may be evident, but so was the strength of the community that would not give up on itself. Chinatown, too, was like that to me. Both minority ghettos within cities, hanging on as hard as it could. But that’s where the comparison stops. I was able to go beyond the boundaries of San Francisco Chinatown without being in imminent physical danger -- hateful stares and verbal insults notwithstanding -- but in Hattiesburg, I knew that going beyond borders one could end up being dead. I had learned about how Chinatowns were burned down to the ground and about Chinese lynching of the past, but I did not know that was still happening -- before my eyes, right then and there in the Deep South, to another race of people.” On her first day working for the Delta Ministry, Marion Kwan was tasked with attending the trial of a fellow civil rights activist from the North who had been arrested for walking alone by the highway. Southern jails were widely known to be dangerous for any civil rights workers, and so a strong presence from the movement was necessary during the trial proceedings. Before the trial could commence, however, Kwan and the 9 other civil rights workers there had to be divided into the “white” and “colored” sections. After forcing the Black activists to the “colored” section, the Deputy Sheriff apparently did not know where to place Marion. After a minute of whispering between the Judge and the Deputy Sheriff, the latter shocked the court by dismissing the case altogether. As Kwan said about the incident: “For that moment anyway, the conscience of the Nation sat in limbo and helped free my fellow-freedom fighter. That is the irony of racism. It’s not about color, it’s about human dignity and equal rights.” For the next few years, Kwan continued working in the movement: registering Black citizens as voters, organizing grassroots groups, and reaching out to others in the community. She eventually moved back to her home city of San Francisco, bringing with her the lessons she learned in Mississippi about community resilience, self-determination, civil rights and oppression. Back in San Francisco, Kwan continued to work in grassroots community organizations as well as national and international social justice. She worked as a Head Start Pre-K teacher in Chinatown, served as the YWCA Young Adult Program Director for a time, did social work for the International Rescue Committee in Hong Kong, and protested the US involvement in the war in Vietnam. Kwan is still alive today, continues to give interviews and work for social justice, and finds great inspiration in the new movement for Black lives. Patsy Mink Patsy Mink was the first woman of color and first Asian-American woman elected to Congress, representing the State of Hawai’i for 24 years from 1965 to 1977, then from 1990 to 2002. As a third-generation Japanese-American woman in ethnically diverse Hawai’i, Mink experienced One of the early examples of Patsy Mink’s commitment to justice occurred during her first year at the University of Nebraska when she organized her fellow students and successfully fought against segregated dorms. On her first day in Congress, Mink proposed and successfully passed a resolution protesting British nuclear testing in the South Pacific. She would go on to write the first draft of Title IX, the law that protects against discrimination based on gender in public schools and any other federally-funded education program; Mink would also co-write the final draft of the law. As the conflict in Vietnam increased in intensity and spread into Cambodia and Laos, Mink consistently criticized the United States’ critical role in escalating and accelerating the violence. In the second half of her career in Congress, Mink opposed the Supreme Court nomination of Clarence Thomas, co-leading a protest march to the Capitol to force the Senate Judiciary Committee to hear Anita Hill’s accusations of sexual assault against Thomas. Mink worked tirelessly to restore, maintain, and progress civil rights and socio-economic protections that had been neglected or diminished since the last time she was in Congress in the ‘60s and ‘70s. She opposed Republican-sponsored welfare reform laws, which would have gutted the protections and programs she had dedicated herself to defending. She was a co-sponsor of the original DREAM Act, which would provide basic civil rights protections for undocumented minors in the United States. From the moment it was proposed to the day of her death, Mink vehemently opposed the formation of the US Department of Homeland Security, presciently warning against the kinds of human rights abuses the US government perpetrated on Japanese-American ethnic minorities during the Second World War. Patsy Mink passed away on August 30, 2002 at the age of 74, just one week after winning in the 2002 primary; later that year, Congress officially renamed Title IX to the “Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act” in honor of her significant contributions to the landmark legislation. Sources: Aguilar-San Juan, Karín. “‘We Are Extraordinarily Lucky to Be Living in These Times’: A Conversation with Grace Lee Boggs.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 36, No. 2 (2015), pp. 92-123. University of Nebraska Press. Alexander, Kerri Lee. “Patsy Mink: 1927-2002.” National Women’s History Museum, 2019 (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/patsy-mink “Asian Americans in the People’s History of the United States.” Zinn Education Project (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/asian-americans-and-moments-in-peoples-history/#Patsy_Mink “Grace Lee Boggs.” Americans Who Tell the Truth (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.americanswhotellthetruth.org/portraits/grace-lee-boggs Kwan, Marion. “Fighting for Civil Rights in Hattiesburg, MS in 1965.” Eastwind: Politics & Culture of Asian America, 2020 (accessed 17 March 2021). Kwan, Marion. “They Hadn’t Counted On Me Comin’.” Civil Rights Movement Archives, 2016 (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.crmvet.org/nars/kwan-ct.htm McFadden, Robert D. “Grace Lee Boggs, Human Rights Advocate for 7 Decades, Dies at 100.” The New York Times, 5 October 2015 (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/06/us/grace-lee-boggs-detroit-activist-dies-at-100.html “Oral History/Interview: Marion Kwan March 2016.” Civil Rights Movement Archives, 2016 (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.crmvet.org/nars/kwan16.htm “Patsy Mink.” National Park Service (accessed 17 March 2021). https://www.nps.gov/people/patsy-mink.htm Tomorrow marks the 91st anniversary of the start of the famous Salt March, which inspired millions across British India to nonviolently rebel against their colonial masters. Although it was not the first campaign that Mahatma Gandhi led to resist British rule, it has been described as the event that transformed the thinking of myriad average Indians to envision self-government. Also known as the Salt Satyagraha (loosely, “truth-power”), the Salt March proved the power of nonviolent mass resistance, the prudence of focusing protest on a universally-used commodity, and the vital role of women in the independence movement. The Salt March was one of the most influential nonviolent direct action campaigns in history, inspiring colonized and oppressed peoples around the world to organize their own nonviolent mass resistance campaigns.

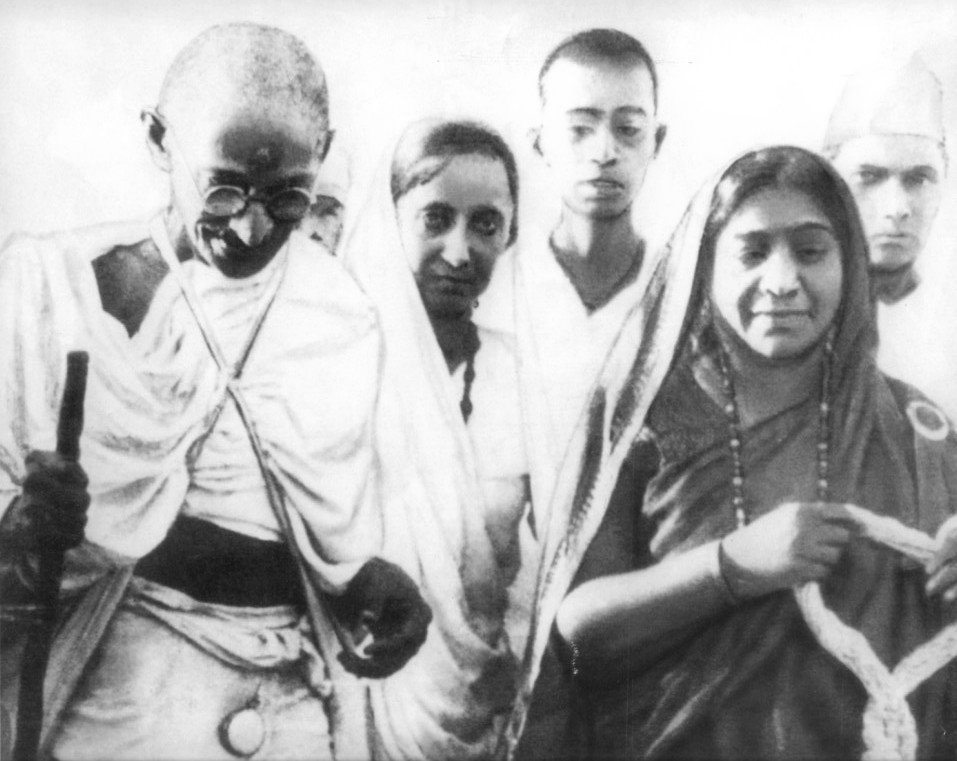

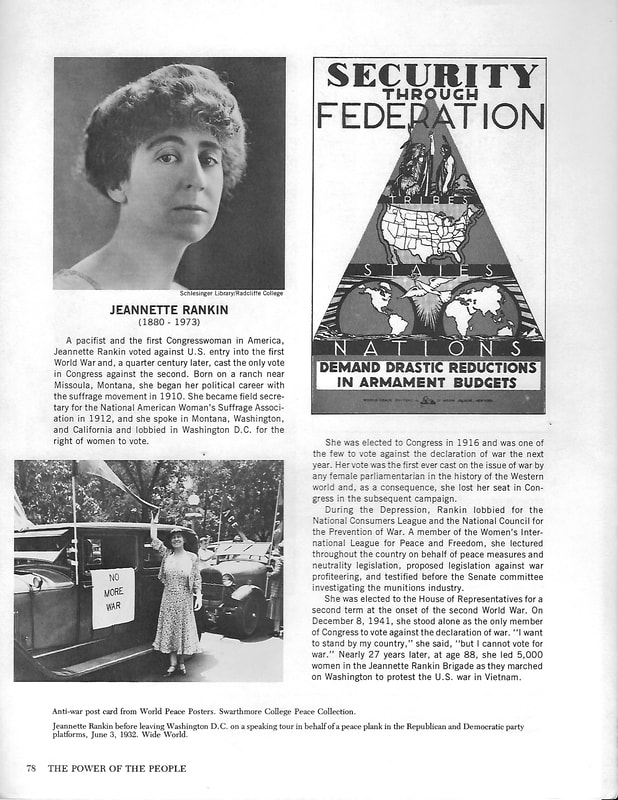

For almost 200 years of the modern era, much of south Asia including modern-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh was ruled by British entities in a vastly exploitative colonial system: first by the British East India Company starting in 1757, and then by the British Crown directly following the Indian Rebellion of 1857. During that time, British economic interests had come to monopolize and heavily tax entire industries in the region, including salt. Although the taxation of salt originated in ancient times, the tax burden increased dramatically with British Imperial rule, affecting every social class in British India. Thus, in December 1929 when the Indian National Congress’ demands for independence from the British were denied, and leaders were deciding on what form their mass civil disobedience should take, Gandhi suggested the salt tax. The original plan was for Gandhi and 78 trusted volunteer men following strict discipline to start the 240 mile walk from the Sabarmati Ashram in western British India to Dandi on the coast. The march would commence on March 12, 1930. In the weeks leading up to the event, Gandhi issued regular and increasingly dramatic statements to the Indian and international press about independence and his expectation of arrest. Along the 24-day walk itself, in the villages the group passed, Gandhi would stop to give speeches attacking the salt tax and British rule generally. Thousands would gather to hear what the man had to say. The international media coverage made Gandhi and this new stage of the Indian independence movement world-famous. When Gandhi and the satyagrahis reached the beaches of Dandi on April 5, he famously picked up a lump of salty mud and declared, “With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire.” He then boiled the mud in saltwater, producing usable salt, defying the British salt monopoly, and forcing colonial authorities to recognize that this satyagraha nonviolent mass action represented a real threat to their rule. Sarojini Naidu, first woman-President of the Indian National Congress, met Gandhi and the 78 male satyagrahis in Dandi. Naidu was one of the most prominent Indian politicians of any gender at the time, and criticized Gandhi for excluding women from the original Salt Satyagraha plan. Naidu encouraged other women to take an active part in the satyagraha movement, going further than Gandhi’s call for women to stick to less risky forms of protest, like picketing shops. Thousands across British India began collecting, producing, processing, selling, and buying illegal salt -- many of whom were women defying Gandhi’s suggestion to stay in their separate sphere. These seemingly little acts of civil disobedience were all the more meaningful because they were small acts in which nearly anyone could participate. The fact that the matter was salt was especially close to the daily issues of women: with household cooking traditionally left to wives and mothers, these women understood the importance of salt. But since everyone must eat, the salt tax and rebellion against it affected Indians of all genders, ages, and social classes. The march to Dandi was just the first step of the Salt Satyagraha. Since reaching Dandi and producing the salt in early April, the Salt Satyagraha had inspired countless people to commit mass civil disobedience on their own, and several women filled the need for local leadership. On April 6, the same day that Gandhi first produced the illegal salt, Kamaladevi Chattopadhayay organized and led women to start their own illegal salt production. On April 13, women held a conference in Dandi affirming their commitment to the independence movement and refusing to be sidelined by men in the struggle. On April 16, Chattopadhayay led 500 people to protest the Wadala salt depot outside Bombay (now Mumbai). Around the same time, the writer Lilavati Munshi led a group to the Wadala salt depot for a similar purpose. These and other lesser-known women were beaten, burned, and arrested, but their actions proved to be absolutely instrumental to the movement’s success. For the second step of the Salt Satyagraha, Gandhi planned a nonviolent raid of the Dharasana salt works, but was arrested in the night before the march and raid began. The Indian National Congress appointed the widely respected judge Abbas Tyabji to take over leadership of the action; Kasturbai Gandhi, the wife of Mohandas Gandhi, stepped up to the leadership role as well. But when both Tyabji and Kasturbai Gandhi were also arrested, it was Sarojini Naidu who took up the mantle and led the Dharasana Satyagraha. Though they were unsuccessful at raiding the site, the hundreds of protesters bravely withstood the violent tactics of the colonial authorities. They experimented with such strategies as the sit-down protest, as well as the strategy of exposing the brutish violence of the British in dealing with unarmed and nonviolent protesters; both would become popular and effective strategies during the US civil rights and antiwar movements. While it took 17 more years for south Asia to win independence from Britain, the 24-day march to Dandi and the rapid spread of the Salt Satyagraha campaign was a turning point in the struggle for many reasons. After the initial exclusion from the Salt March itself, enormous numbers of women -- most from modest backgrounds -- participated in active roles at every level of resistance for the first time in the independence movement. The dramatic entry of these women into the movement further inspired people of all genders across British India to stand up to colonial rule. Once south Asians understood they could stand up to the brutality of the British Empire without resorting to brutality themselves, they continued and eventually succeeded in their nonviolent resistance against the largest empire in history, inspiring independence movements around the world and creating a model that continues to be used and developed today. Sources: Chatterjee, Manini. “1930: Turning Point in the Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle.” Social Scientist, vol. 29, no. 7/8, 2001, pp. 39–47. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3518124 Live History India. “Women, Salt and Satyagraha: A Look at the Historic Protest at Mumbai’s Chowpatty Beach in 1930.” The Better India. 15 August 2017. https://www.thebetterindia.com/111930/the-chowpatty-satyagraha/ Karlekar, Malavika. “A Fistful of Salt: How Women Took Charge of the Dandi March.” The Wire. 30 January 2020. https://thewire.in/women/women-dandi-march-gandhi One hundred and four years ago to the day, Jeannette Rankin was seated as the first woman member of the US Congress. In her two nonconsecutive terms representing Montana, Rankin caused intense controversy for her work in the women’s suffrage movement, for her efforts to secure protections for workers, and most of all for her outspoken opposition to war. The uncompromising stance that she maintained over several decades on such controversial issues inspired many of her peers, inspired many the younger generation in the 1960s and ‘70s, and continues to inspire those who work against the grain in order to improve society for all.

Up until well into her twenties, Jeannette Rankin lived a fairly sheltered life in rural Missoula, Montana. She earned a Bachelor of Science in biology from the University of Montana in 1902, then worked as a teacher and a seamstress before becoming a caretaker for her sick father. It was not until 1904 that Rankin witnessed her first glimpses of urban, industrial poverty alongside unimaginable extravagance and wealth during a visit to the east coast. Returning home, Rankin began to read all the material she could find on progressive ideas, especially the issues related to women. After seeing the same inequality in San Francisco during another trip in 1907, Rankin was compelled to move to the city to teach recently-arrived immigrants at a private settlement house, then moved to the east coast to attend the New York School of Philanthropy in 1908. After graduating, Rankin moved back west to Washington state and became involved in the women’s suffrage campaign in Seattle. After the campaign was won in 1910, making Washington the fifth state in the Union to extend voting rights to white women, Rankin got a job as a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), traveling across the country to organize local women’s suffrage campaigns. Following the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, which killed 146 garment workers in New York City, Rankin also organized the immigrant women still working in similarly dangerous conditions in Manhattan’s Garment District. Meanwhile, Rankin led a revival of the women’s suffrage movement in Montana starting with a speech before the Montana legislature in 1911 -- the first woman to address the Montana legislature. The state legislature would pass a bill expanding voting rights to white women in 1913, and the public voted in favor of a women’s suffrage referendum in 1914, making Montana the 13th state in the Union to legalize women’s suffrage and the second women’s suffrage campaign that Rankin helped carry to victory. Hoping to build off of the landmark victory in her home state, Jeannette Rankin declared her candidacy for a Congressional seat representing Montana in 1916. Her platform followed a typical progressive slate including universal suffrage, child welfare legislation, and alcohol prohibition. Less universal among progressives was her outspoken opposition to US involvement in the First World War. But despite promoting what some may have thought were radical positions at the time, and despite being ignored by most of the newspapers in the state, Rankin won the second-most number of votes in Montana that year, becoming the first woman to be elected to Congress in the United States. Many women voters who knew the work Rankin had already done for them cast their votes for her, but Rankin’s modern, progressive platform convinced enough male voters as well that she beat the next runner-up by 6000 votes. On her first day as a House Representative, Rankin introduced the Susan B. Anthony amendment to guarantee and protect women’s suffrage in the US Constitution. Later that same evening, President Wilson requested Congress to declare war on Germany to make the world “safe for democracy.” In the days between Wilson’s request and the actual vote, Rankin’s colleagues and even her brother Wellington advised her to go against her personal feelings and vote in favor of the war. But she was not alone in her opposition to entering the war: the majority of the messages she received from her constituents in Montana urged her to vote against war, and 49 other House members also planned to vote against. Rankin apparently considered abstaining, but ultimately cast her vote, saying, “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.” The reaction was mostly negative and singled out Rankin despite the many other men who voted with her. In a parallel to civil rights leaders who expressed antiwar sentiments later on, Rankin was accused by some of her allies of sabotaging the broader women’s suffrage movement with her personal opinions. Still, Rankin continued leading the universal suffrage cause as the only woman in Congress. She was a founding member of the Committee on Woman Suffrage and continued to passionately argue for the Susan B. Anthony amendment. At one point, Rankin addressed the hypocrisy of Congress with regards to war and democracy: “How shall we explain to them the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted for war to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?” The measure was ultimately passed as the Nineteenth Amendment the year after her term ended. During her first term, Rankin also investigated accounts of worker abuse in government bureaus, as well as in the industries that encouraged the United States to join the war in the first place. In the two decades after her first term in Congress, Jeanette Rankin continued some of that work within a number of local, national, and international progressive organizations. She worked as a lobbyist, a field secretary, and traveling speaker, advocating for social welfare, increased education, and worker and consumer protections. When Senator Gerald Prentice Nye published his “merchants of death” investigation into powerful US arms manufacturers and their role in dragging the country into the First World War, Rankin publicized the findings. Those arms manufacturers had only grown in the last couple decades, and seemed to be sending the United States on another warpath. Eventually, the imminent threat of another war led Rankin to run in the Montana elections in 1940 and defeat her anti-Semitic opponent for the House seat. Early in her second term in Congress in 1941, Jeannette Rankin unsuccessfully introduced legislation to limit the range of the US military, hoping to make it legally impossible to join the brewing global conflict. On the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor later that year, unlike in her last term, Rankin was the sole member of both houses in Congress to vote against declaring war. The reaction to her vote was so intense that afterward, Rankin was forced to take refuge in a phonebooth while reporters and other Congress members harassed her; she ultimately had to be escorted out by police. The vote effectively ended her political career, but after her second term, Rankin continued to travel and learn. She became more aware of the global decolonization movement, went to India several times to learn Gandhian nonviolent resistance, and continued to speak out against war and exploitation. In the 1960s, as the United States involved itself more in the Vietnam War, a new generation of war resisters emerged. Rankin had purposely stayed out of the headlines since she left Congress, but the accelerating war in Vietnam pushed Rankin, now in her eighties, to participate in the new antiwar movement. In advanced age and suffering from a painful medical condition, Rankin nevertheless helped to organize a coalition of 5000 women and several women’s peace organizations to form the largest women’s march on Washington since the 1913 suffrage march. The Jeannette Rankin Peace Brigade, as it was named, included several women’s groups which emphasized the nurturing, protecting, and mourning roles of traditional mothers and wives. But the group also included a faction which called for the need to “bury traditional womanhood” and to draw feminine political power from new sources -- Rankin, herself, never married or became a mother, after all. As a trailblazer of women’s rights, a nonconformist in many ways, and a courageously consistent voice for peace and social justice, a great variety of women in the 1960s and ‘70s found inspiration in Jeannette Rankin. Indeed, as we today grapple with rollbacks of civil rights protections, worsening worker exploitation, the continual growth of the military-industrial complex, and an expansion of our endless wars, we may do well to look to Jeannette Rankin’s lifelong resistance to violence and injustice, and find inspiration ourselves. Sources: O’Brien, Mary Barmeyer. Jeannette Rankin 1880-1973: Bright Star in the Big Sky. Falcon Press Publishing Co., Inc., 1995. “Rankin, Jeannette.” History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives. https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/R/RANKIN,-Jeannette-(R000055)/ Smith, Norma. Jeannette Rankin: America’s Conscience. Montana Historical Society Press, 2002. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed