|

Tomorrow marks the 91st anniversary of the start of the famous Salt March, which inspired millions across British India to nonviolently rebel against their colonial masters. Although it was not the first campaign that Mahatma Gandhi led to resist British rule, it has been described as the event that transformed the thinking of myriad average Indians to envision self-government. Also known as the Salt Satyagraha (loosely, “truth-power”), the Salt March proved the power of nonviolent mass resistance, the prudence of focusing protest on a universally-used commodity, and the vital role of women in the independence movement. The Salt March was one of the most influential nonviolent direct action campaigns in history, inspiring colonized and oppressed peoples around the world to organize their own nonviolent mass resistance campaigns.

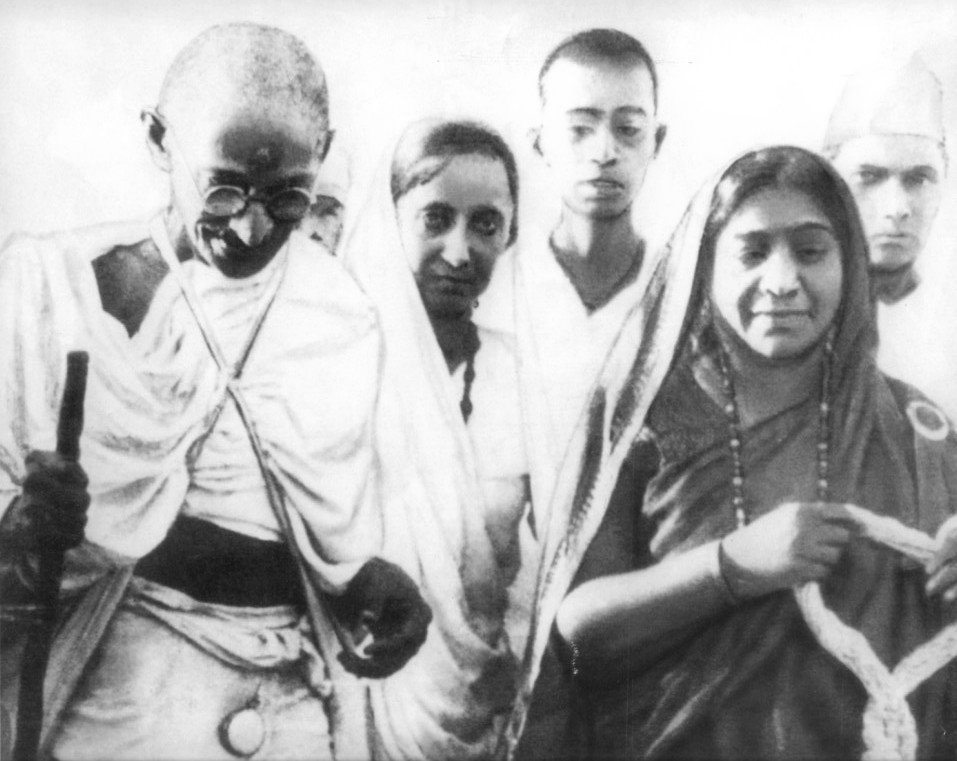

For almost 200 years of the modern era, much of south Asia including modern-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh was ruled by British entities in a vastly exploitative colonial system: first by the British East India Company starting in 1757, and then by the British Crown directly following the Indian Rebellion of 1857. During that time, British economic interests had come to monopolize and heavily tax entire industries in the region, including salt. Although the taxation of salt originated in ancient times, the tax burden increased dramatically with British Imperial rule, affecting every social class in British India. Thus, in December 1929 when the Indian National Congress’ demands for independence from the British were denied, and leaders were deciding on what form their mass civil disobedience should take, Gandhi suggested the salt tax. The original plan was for Gandhi and 78 trusted volunteer men following strict discipline to start the 240 mile walk from the Sabarmati Ashram in western British India to Dandi on the coast. The march would commence on March 12, 1930. In the weeks leading up to the event, Gandhi issued regular and increasingly dramatic statements to the Indian and international press about independence and his expectation of arrest. Along the 24-day walk itself, in the villages the group passed, Gandhi would stop to give speeches attacking the salt tax and British rule generally. Thousands would gather to hear what the man had to say. The international media coverage made Gandhi and this new stage of the Indian independence movement world-famous. When Gandhi and the satyagrahis reached the beaches of Dandi on April 5, he famously picked up a lump of salty mud and declared, “With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire.” He then boiled the mud in saltwater, producing usable salt, defying the British salt monopoly, and forcing colonial authorities to recognize that this satyagraha nonviolent mass action represented a real threat to their rule. Sarojini Naidu, first woman-President of the Indian National Congress, met Gandhi and the 78 male satyagrahis in Dandi. Naidu was one of the most prominent Indian politicians of any gender at the time, and criticized Gandhi for excluding women from the original Salt Satyagraha plan. Naidu encouraged other women to take an active part in the satyagraha movement, going further than Gandhi’s call for women to stick to less risky forms of protest, like picketing shops. Thousands across British India began collecting, producing, processing, selling, and buying illegal salt -- many of whom were women defying Gandhi’s suggestion to stay in their separate sphere. These seemingly little acts of civil disobedience were all the more meaningful because they were small acts in which nearly anyone could participate. The fact that the matter was salt was especially close to the daily issues of women: with household cooking traditionally left to wives and mothers, these women understood the importance of salt. But since everyone must eat, the salt tax and rebellion against it affected Indians of all genders, ages, and social classes. The march to Dandi was just the first step of the Salt Satyagraha. Since reaching Dandi and producing the salt in early April, the Salt Satyagraha had inspired countless people to commit mass civil disobedience on their own, and several women filled the need for local leadership. On April 6, the same day that Gandhi first produced the illegal salt, Kamaladevi Chattopadhayay organized and led women to start their own illegal salt production. On April 13, women held a conference in Dandi affirming their commitment to the independence movement and refusing to be sidelined by men in the struggle. On April 16, Chattopadhayay led 500 people to protest the Wadala salt depot outside Bombay (now Mumbai). Around the same time, the writer Lilavati Munshi led a group to the Wadala salt depot for a similar purpose. These and other lesser-known women were beaten, burned, and arrested, but their actions proved to be absolutely instrumental to the movement’s success. For the second step of the Salt Satyagraha, Gandhi planned a nonviolent raid of the Dharasana salt works, but was arrested in the night before the march and raid began. The Indian National Congress appointed the widely respected judge Abbas Tyabji to take over leadership of the action; Kasturbai Gandhi, the wife of Mohandas Gandhi, stepped up to the leadership role as well. But when both Tyabji and Kasturbai Gandhi were also arrested, it was Sarojini Naidu who took up the mantle and led the Dharasana Satyagraha. Though they were unsuccessful at raiding the site, the hundreds of protesters bravely withstood the violent tactics of the colonial authorities. They experimented with such strategies as the sit-down protest, as well as the strategy of exposing the brutish violence of the British in dealing with unarmed and nonviolent protesters; both would become popular and effective strategies during the US civil rights and antiwar movements. While it took 17 more years for south Asia to win independence from Britain, the 24-day march to Dandi and the rapid spread of the Salt Satyagraha campaign was a turning point in the struggle for many reasons. After the initial exclusion from the Salt March itself, enormous numbers of women -- most from modest backgrounds -- participated in active roles at every level of resistance for the first time in the independence movement. The dramatic entry of these women into the movement further inspired people of all genders across British India to stand up to colonial rule. Once south Asians understood they could stand up to the brutality of the British Empire without resorting to brutality themselves, they continued and eventually succeeded in their nonviolent resistance against the largest empire in history, inspiring independence movements around the world and creating a model that continues to be used and developed today. Sources: Chatterjee, Manini. “1930: Turning Point in the Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle.” Social Scientist, vol. 29, no. 7/8, 2001, pp. 39–47. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3518124 Live History India. “Women, Salt and Satyagraha: A Look at the Historic Protest at Mumbai’s Chowpatty Beach in 1930.” The Better India. 15 August 2017. https://www.thebetterindia.com/111930/the-chowpatty-satyagraha/ Karlekar, Malavika. “A Fistful of Salt: How Women Took Charge of the Dandi March.” The Wire. 30 January 2020. https://thewire.in/women/women-dandi-march-gandhi Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed