|

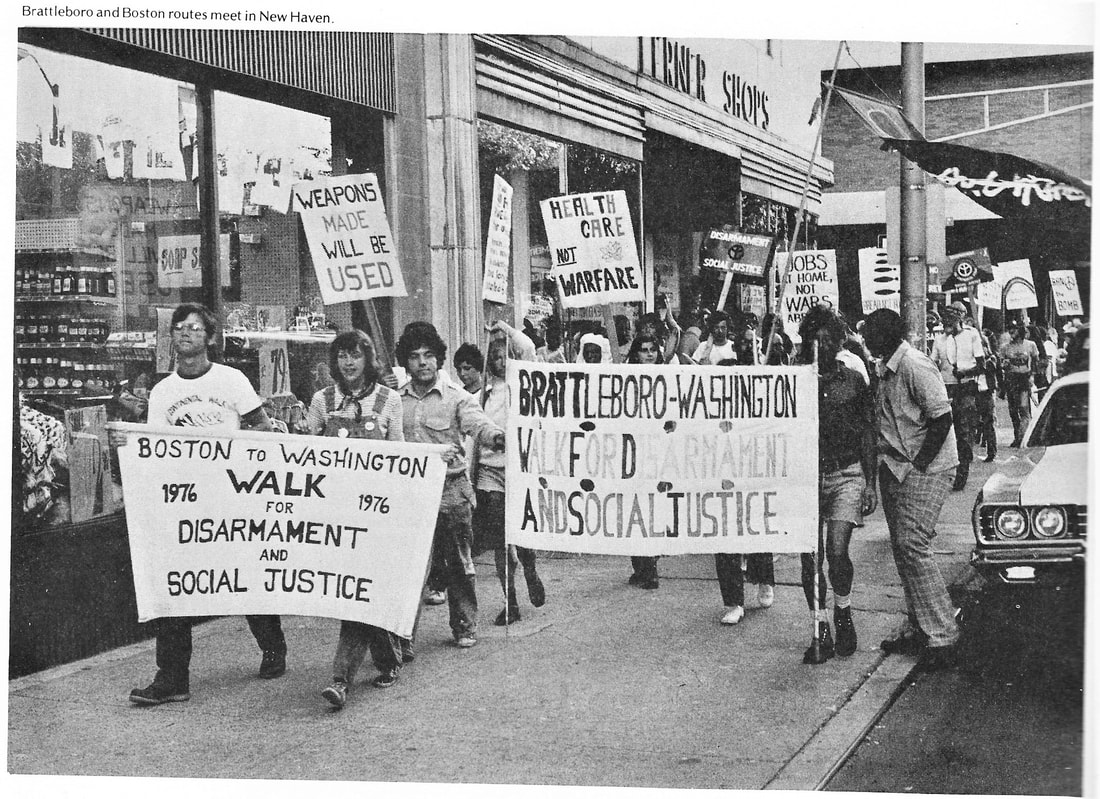

Last Friday, January 22, over thirty-eight individuals gathered in New London, CT to celebrate the United Nations Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) coming into force. Participants held signs thanking the 51 ratifying states on the road to the General Dynamics - Electric Boat engineering building. Those participants belong to a 61-year movement in southeastern Connecticut to raise awareness of the dangers of nuclear weapons and to move the region’s economic reliance away from the military-industrial complex. Indeed, almost exactly 45 years earlier on January 23, 1976, peace activists launched a national action with roots in southeastern Connecticut. Hundreds of people would eventually be organized to cross 34 states and a total of 8000 miles on foot in less than 10 months, all in order to spread the message of peace and justice to big and small communities in a post-Vietnam America. This was the Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice.

The organizers for the Continental Walk were inspired by an earlier project: the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace from 1960-1961. That earlier Walk also had a connection to southeastern CT: the idea for it was first conceived in New London, CT. The San Francisco to Moscow Walk was organized in just a couple short months, with a much more limited number of participants, volunteers, and funds (to read more about it, see our previous posts linked at the end). But the Continental Walk would be different. After 1967, CNVA (which organized the earlier San Francisco to Moscow Walk) merged with the War Resisters League (WRL), and it was WRL that organized the Continental Walk. The goals for the new Walk could be divided into four parts: educating the public about the military-industrial complex, organizing local people for social action and connecting them to greater resources, promoting unity between various disparate groups working for social justice, and reaching out to communities that are often ignored and forgotten. Preparations took eighteen months. Press releases had to be issued, bills tracked and paid, and fundraising orders processed. WRL made t-shirts, leaflets, bumper stickers, posters, and more to advertise and fund the Walk. They had to write, print, and distribute literature, establish routes and acquire permits, and arrange for speakers at various sites. The full name “The Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice” was chosen to emphasize the connections some had made a decade earlier: that the United States was investing so much into war at the expense of the needs of people already here. Incredible sums were (and are) spent researching and producing weapons which, in the best case scenario, would never be used -- while children in America went hungry. They also addressed issues such as racism, sexism, the growing problem of nuclear power, etc. The United States had officially left the Vietnam War in April 1975, less than a year before the Walk began. Many peace activists did not view the withdrawal from Vietnam as an opportunity to pat their own backs and rest on their laurels, but rather the time to maintain the momentum, stir up local organizing, and connect communities to prepare for future resistance. In preparation for the Walk, WRL even reached out beyond the United States, to Japan. Sixteen Buddhist monks and nuns from the Japan Buddha Sangha eventually joined the Continental Walk, ultimately establishing a permanent presence in the United States. Shortly after the main group took off from Ukiah, CA, several regional WRL and other co-sponsoring groups like the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) , the Catholic Worker, SANE, Socialist Party USA, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Women Strike for Peace worked to coordinate and train regional “feeder” routes. Each route had its own unique logistical challenges. On January 31, two hundred people met in Hartford, CT to celebrate the launch of the San Francisco feeder group and to drum up local interest in organizing New England feeder groups. Several months later in July 1976, the New England CNVA in Voluntown became the main hub for training and preparing walkers for the Northeast Route. Six people joined with the AFSC staff, spending six weeks preparing their minds and bodies for the difficulties of walking 20 miles a day, and organizing the logistics for the walkers. The Continental Walk also has another special connection to the Voluntown Peace Trust. Our current Chair of the Board of Directors, Joanne Sheehan (as well as her now-partner Rick Gaumer), served as part of just four national organizers in the WRL New York office at the time the Walk was happening, and was instrumental in helping to overcome some early challenges. Unlike the earlier San Francisco to Moscow Walk, which had a single small core group of walkers, too many people wanted to participate in the Continental Walk. A few of the core group invited anyone to walk with them, including people who did not agree to the guidelines. Soon, local organizers were unable to provide hospitality and assistance to the growing numbers of sometimes undisciplined participants. Joanne was one of several organizers who joined the Walk to help reinstate the guidelines, and work with the core group to return to the number of permanent walkers that could be sustained. Now, over 75 years after the first ever use of nuclear weapons in war, 51 governments have come together to assert that such weapons are illegal according to international law. Notably, the United States is not one of the ratifying nations. As the only country to ever use nuclear weapons aggressively in warfare, the United States of America has an unique moral obligation to ratify this treaty and disarm its nuclear weapons program. Just as the Continental Walkers reminded us of this fact in 1976, so too did the folks in New London last Friday. Yesterday, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists released their 2021 statement. It is 100 seconds to midnight, they said, citing how the covid-19 pandemic has exposed so many governments inability to manage massive and catastrophic issues such as climate change and nuclear weapons. And if we want to turn back the clock, perhaps we should take a look at the past. Sources: “Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice Records, 1975-1978.” Swarthmore College Peace Collection, accessed 27 January 2021. http://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/DG100-150/dg135cwdsj.htm Leonard, Vickie and Tom MacLean, Ed. The Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice. Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice, 1977. Lyttle, Bradford. You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. Greenleaf Books, Raymond, New Hampshire: 1966. Mecklin, John, Ed. “This is your COVID wake-up call: It is 100 seconds to midnight.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, accessed 27 January 2021. https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/ More on the earlier San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace: 12/5/2019 https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/permalink/10157606136922978/ 9/17/2020 https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/permalink/10158480028102978/ 9/24/2020 https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/permalink/10158495916447978/ 10/3/2020 https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/1825600097590317 Yesterday, Joseph Biden was inaugurated as the 46th President of the United States of America. To many Americans, this was a moment of immense relief: the authoritarian Donald Trump is finally out of the White House. And yet, many others on the left have already cautioned that a Democratic President is no guarantee for progressive, effective policies. Among Democrats, Biden is known for being a pushover for conservative policies and for being slow to adopt civil rights and other progressive legislation. Though there are recent signs of a progressive turn for Biden, we must not rest on our laurels yet. Indeed, our history shows that we must now work harder and smarter than ever.

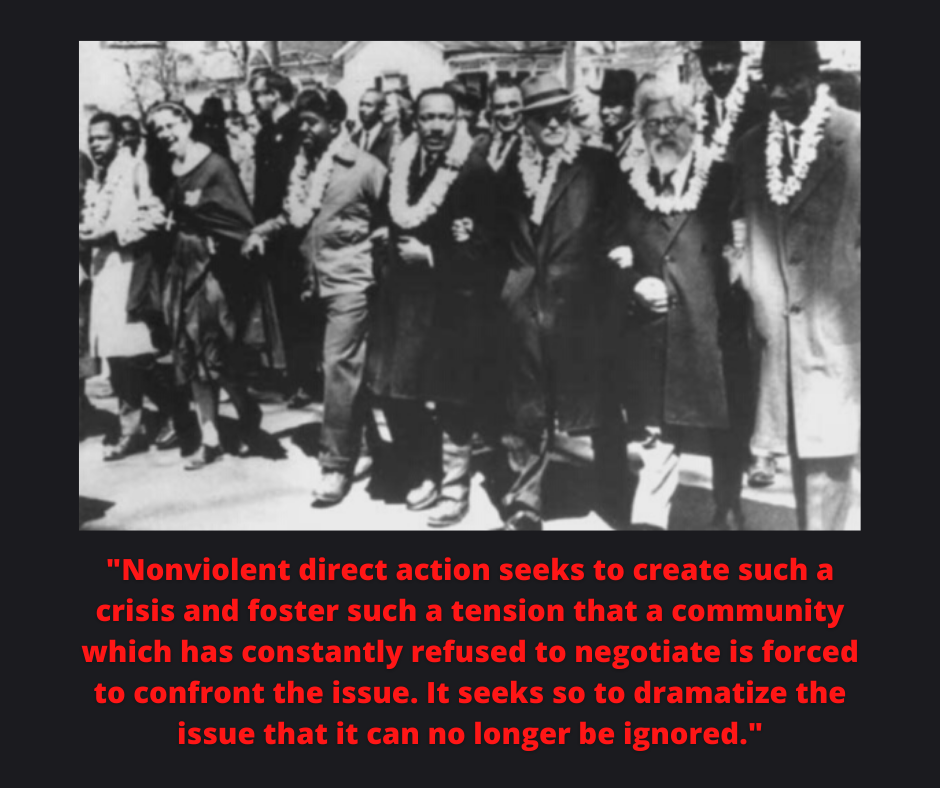

The determination and momentum carried by Dr. King provide an excellent example. Martin Luther King, Jr. did not stop seeking equality when the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 (which outlawed segregation and other forms of discrimination), nor justice when the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 (which removed racist laws that prevented countless Black Americans from voting), but rather continued to aggressively interrogate the root causes of injustice, inequality, and suffering in the United States. Despite Democratic President Johnson’s stated wish to focus on the “war on poverty,” after 1965 LBJ found himself diverting more funds from his “Great Society” project into the actual war in Vietnam. Dr. King clearly saw that militarism consistently funnelled much needed resources from the poor, even when the liberal President devoted to fighting poverty was reluctant to do so. Thus, King’s vision of civil rights and social justice came to include all Americans, regardless of race, suffering under the inequality of modern capitalism. After segregation was outlawed, he started speaking of a “revolution” in an era when peoples around the world were violently struggling to assert their rights, dignity, and self-determination after decades, sometimes centuries of colonization. Social and liberation movements have always demonstrated their strength most effectively on the streets in mass actions. But, of course, Dr. King meant a nonviolent revolution, one in which the nonviolent means would be consistent with just ends, one that would require immense cooperation, discipline, and organization. Nonviolence is sometimes criticized for being too insular and for caring more about the individual’s moral egotism than about improving real lives in society, but Dr. King’s nonviolence was always rooted in mass action and tangible results: from the 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott to the 1963 March on Washington to his last campaign, the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike. As King wrote in his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail": "Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored." Crucially, such action can force a community to confront the issue while still maintaining a certain moral legitimacy. Asking to consider legitimacy is not a call for respectability politics; it’s a call for practical strategic thinking. Donald Trump may be out of the White House, but the White supremacist / conspiracy theory movement he stirred can be found in communities all across this country. Their ideology is manifestly violent. But for every person who went to the Capitol to protest the election results on January 6, there were several more watching from home who had considered going but didn’t. With the authoritarian defeated but the threats to our society spread all across the country, now is our chance to frame the issues, expand our alliances, and inoculate our communities against such a movement. Source: King, Jr., Dr. Martin Luther. “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” 1963. https://letterfromjail.com/ Could Trump launch a nuke in the last week of his term? Following the right-wing conspiracy theorist insurrection that was instigated by President Trump at the Capitol last week, many have been wondering this question. Some might find the question irrelevant and silly -- what do nuclear weapons have to do with a domestic political conflict? -- and sweep questions of strategy, morality, power, and accountability under the rug. Others, however, have realized that the question is the logical end of US Presidential overreach, and one that should raise more questions as well. Why is the US nuclear arsenal under the command of one person, the President? What are they there for? And considering the history of deranged leaders of wealthy countries with powerful militaries, are these weapons safe to keep around at all? What can we do to keep ourselves and each other safe from nuclear weapons?

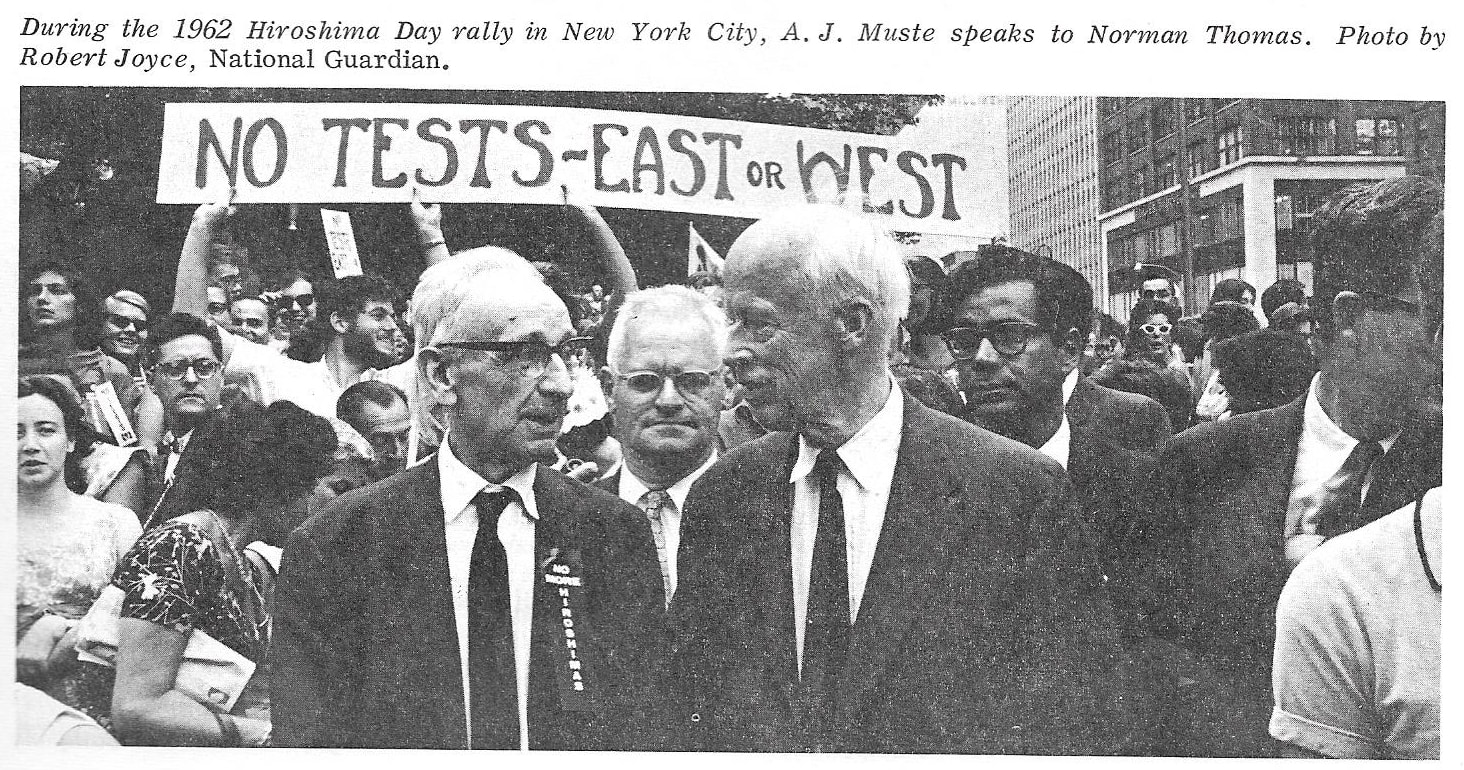

Activists have been asking these kinds of questions for over 70 years. Indeed, there has always been a pacifist faction of the left arguing for unilateral disarmament, even preceding the invention of nuclear arms. But everything changed after the United States dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the years immediately following, the former labor organizer A.J. Muste tried to reach his fellow Christians with the message of disarmament, especially in the face of this new super weapon -- but found that the vast majority of liberal Protestants had come to adopt a “realism” that, in the words of Muste biographer Leilah Danielson, “devolved into a kind of American moral complacency and self-satisfaction that exempted the United States from any responsibility in the rising tensions of the Cold War” (Danielson 247). He also sought to convince the country’s nuclear physicists and engineers that building these weapons at all was inconceivably dangerous, but was met with a different kind of obstinance: the scientists believed that peace could only come from supranational, one world organization and governance -- a long-shot, most of them would admit, given the tense relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union at the time. Failing with the majority of liberal Protestants and the scientific community, in 1947, Muste brought together pacifists from across the United States to discuss strategy in the new atomic era and the emerging Cold War. By then, Muste had become a prominent public critic of nuclear weapons. Disagreements with the more liberal pacifists, who still believed in working within the system, led Muste and others to hold a second conference in 1948. From this second conference would eventually develop a whole new anti-nuclear pacifist movement. In the 1950s, more groups began to emerge or shift their missions to include opposition to nuclear weapons: the Committee for Nonviolent Action (predecessor to the Voluntown Peace Trust), the War Resisters League, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), the Catholic Worker Movement, and more. Muste himself held a leading position in those first three groups listed, and was a close friend of Dorothy Day, a prominent leader of the Catholic Workers. All of these groups came to the same conclusion: nuclear arms production is a primary obstacle to world peace, and unilateral disarmament is the only solution to the existential threat of the Cold War. The United States had both the practical and ethical responsibility to be the first superpower to reject the nuclear arms system that it had started, since the United States alone was the only one to ever use such weapons in war. In the absence of a moral government, these groups argued, the ethical individual should refuse to participate in the unjust society. Stop following the script. Don’t play along. Surely we can find better uses for these physicists and engineers. Surely our spiritual lives would be richer if the world was consistent with our values. Resistance to nuclear arms in the United States have waxed and waned over the decades. In the early 1960s, small groups protested at nuclear and weapons production sites, including at General Dynamics Electric Boat in the New London-Groton area. Daring young activists in small sailboats like The Golden Rule chased nuclear-armed submarines, trying to board them -- some even succeeded. Women Strike for Peace organized the largest national women’s peace protest of the 20th century: 50 thousand women in 60 cities specifically calling for nuclear disarmament. Long-term peace walks, some lasting several months and covering thousands of miles, started to expand across the country and the world. Perhaps the most famous anti-nuclear protest occurred in 1977, when 1414 protesters of the Clamshell Alliance and other allied groups were arrested at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant and held in National Guard armories for 12 days. But five years later, in 1982, one million people in NYC’s Central Park protested against nuclear arms and the arms race -- the largest political demonstration in American history. Since the 1980s, the Cold War has ended and the arms race dissolved, but the issue of nuclear weapons has not closed. In some ways, without the principle of “mutually assured destruction” that supposedly kept the Cold War from “heating up,” the use of nuclear weapons in war is more likely now than it was forty years ago. But on January 22, 2021, people around the world will celebrate the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) entering into force. This is perhaps the first major step for global nuclear disarmament, what the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICANW) describes as “the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons.” On that afternoon from 2:45-4pm, volunteers will gather in New London to express thanks to each of the 51 nations that have ratified the Treaty Prohibiting Nuclear Weapons. Participants will stand along the route driven by General Dynamics Electric Boat employees. The goal is to honor the hard work of the treaty ratifiers, to call on the United States to begin the process of disarmament, and to make EB engineers consider the danger they are actively designing into the world. (To participate or learn more, please visit the RSVP form for this event here: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdF0x6tdnyisX9ACu2seMJoX21liUVGZOXls84O4-ggynnQZQ/viewform) Two days after the insurrection, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi called General Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to subtly ask him to prevent President Trump from commanding the nuclear arsenal. Milley argued that that was not his role, pointing to the legal process and norms in place. Checks and balances are great when they work, but under such an obviously unstable person as Donald Trump, it’s hard not to wonder at which point one would have to stop going along with it all. Sources: Danielson, Leilah. American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014. Sanger, E. David and Eric Schmitt. “Pelosi Pressed Pentagon on Safeguards to Prevent Trump From Ordering Military Action.” The New York Times, 8 January 2021 (updated 13 January 2021). On January 8, 1885, Abraham Johannes Muste was born to a humble, working-class family in Holland. At age 6, Muste and his family immigrated to a Dutch community in Grand Rapids, Michigan. A.J., as he would come to be known, was strongly influenced by his religious upbringing, instilling in him a deep devotion to justice and peace. But he never let his spiritualism cloud his view of reality. A story from A.J.’s seminary days tells of a friend warning him against reading Darwin. Muste’s response was to read all of Darwin’s writings he could get. Charismatic and well-loved by all, he was the captain of the basketball team at Hope College, graduating valedictorian. At the much more conservative New Brunswick Theological Seminary, Muste chafed against the lack of academic rigor and outdated thinking. And yet, despite his open criticism of the school’s academics, he remained popular with professors and fellow students when he graduated in 1909.

Muste took additional classes in philosophy and theology during and after his time at New Brunswick Theological Seminary. While attending lectures by William James in New York City, Muste met the great progressive theorist John Dewey. The two became good friends. Muste became influenced by Dewey’s theory of pragmatism: that learning and deep understanding is best achieved through direct experience. This was also the time in which Muste became more interested in the “Social Gospel” movement as well as other progressive and left ideas. He left his pastorship and the Dutch Reformed Church in 1914 over its conservatism, but joined the radical Christian-oriented Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) shortly after its founding in 1916. He resigned again from another pastor position over his pacifism in 1917, as the United States entered the First World War. For a time, Muste worked for the ACLU aiding conscientious objectors. Then, in 1919, A.J. Muste got involved with Lawrence Textile Strike. We have told the story of the 1919 Lawrence Textile Strike before (https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/permalink/10158108528137978/). Almost all outside support for the strike came from the Boston Comradeship, a group of radical pastors which Muste helped found. And so, after a week of picketing and violence, the workers asked Muste to organize and lead them. For the next 16 weeks, Muste personally led a nonviolent strike even as the police became more aggressive, winning public support and ultimately forcing the factory owners to accept most of the workers’ demands. Following this strike, Muste became more involved in the workers movement and socialist politics. For the next 17 years after the 1919 Lawrence Textile Strike, Muste worked on organizing unions, pushing dominant unions like the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to the left, and proving the practicality of nonviolent strikes. Among some of the strikes Muste led include the 1936 Goodyear Tire Strike in Akron, which is the first recorded use of the sit-down technique in a modern civil disobedience action. He became a Marxist-Leninist, a revolutionary, and became convinced of the need for an American labor party. Not all of his endeavors were successful. For two years after his first strike, Muste tried and failed to organize the Amalgamated Textile Workers of America. He had to leave his positions at both religious and secular organizations due to his politics numerous times. He even had to leave his director position at the Brookwood Labor College -- a school to learn labor theory and militancy -- in 1933 due to controversy over his activism. In 1929, Muste helped found the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA), from which the American Workers Party (AWP) was born. Muste’s sharp and effective organizing skills became so deeply associated with the AWP that many contemporaries called the group “Musteites.” Within a few years, the Musteites would merge with the Trotskyist Communist League of America to form the Workers Party of the United States (WPUS). Under the new organization, however, Muste started to become disillusioned with the efficacy of socialist politics, and began to consider leaving the Trotskyist movement. It was 1936 when Muste took a vacation and met the man himself, Leon Trotsky, in exile in Sweden. Muste was impressed, even captivated by Trotsky, but was ultimately unconvinced by the great revolutionary to stay within the movement. By the time Muste had returned to the United States, Muste had decided to retry the revolutionary Christian pacifist path, but now with all that had learned in the labor movement. He would stay that course for the rest of his life. But for Muste, leaving a college, a church, a political party, or a movement did not mean having to burn bridges. He served as the executive director of FOR from 1940-1953. He joined the national committee of the War Resisters League. He became a close friend and ally of Dorothy Day, one of the founders of the direct-actionist Catholic Worker Movement. He mentored the great civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin, who claimed that he never made a difficult decision before discussing it with Muste first. He organized for years against US nuclear weapons policies. He led opposition to US involvement in the Vietnam War, even traveling there with the Committee for Nonviolent Action in 1966. But even as Muste made more connections with new people all the time, he also kept in touch with his past allies: even the communists during the height of McCarthyism, when so many other allies abandoned them. He was trusted by anarchists and pacifists, housewives and union guys, New Left youth and old school socialists. His integrity was legendary. A year after his death in 1967, the War Resisters League began to rent the building at 339 Lafayette Street in Manhattan; they bought the building in 1974 before selling it to the A.J. Muste Institute four years later. From 1978 to 2015, 339 Lafayette Street was known as the “Peace Pentagon” for the number of social justice organizations that were headquartered there, including the War Resisters League, the Socialist Party USA, the Metropolitan Council on Housing, the Catholic Peace Fellowship, Political Art Documentation/Distribution, and more. For decades after his death, the leftists, pacifists, and progressives inspired by A.J. Muste’s example continued to work, if not side-by-side, then under the same roof: a fitting legacy for a person who directly and indirectly affected so many lives. Sources: Danielson, Leilah. American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014. Reyes, Gwen, editor. “WIN: Peace & Freedom Through Nonviolent Action.” 1967. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed