|

On January 8, 1885, Abraham Johannes Muste was born to a humble, working-class family in Holland. At age 6, Muste and his family immigrated to a Dutch community in Grand Rapids, Michigan. A.J., as he would come to be known, was strongly influenced by his religious upbringing, instilling in him a deep devotion to justice and peace. But he never let his spiritualism cloud his view of reality. A story from A.J.’s seminary days tells of a friend warning him against reading Darwin. Muste’s response was to read all of Darwin’s writings he could get. Charismatic and well-loved by all, he was the captain of the basketball team at Hope College, graduating valedictorian. At the much more conservative New Brunswick Theological Seminary, Muste chafed against the lack of academic rigor and outdated thinking. And yet, despite his open criticism of the school’s academics, he remained popular with professors and fellow students when he graduated in 1909.

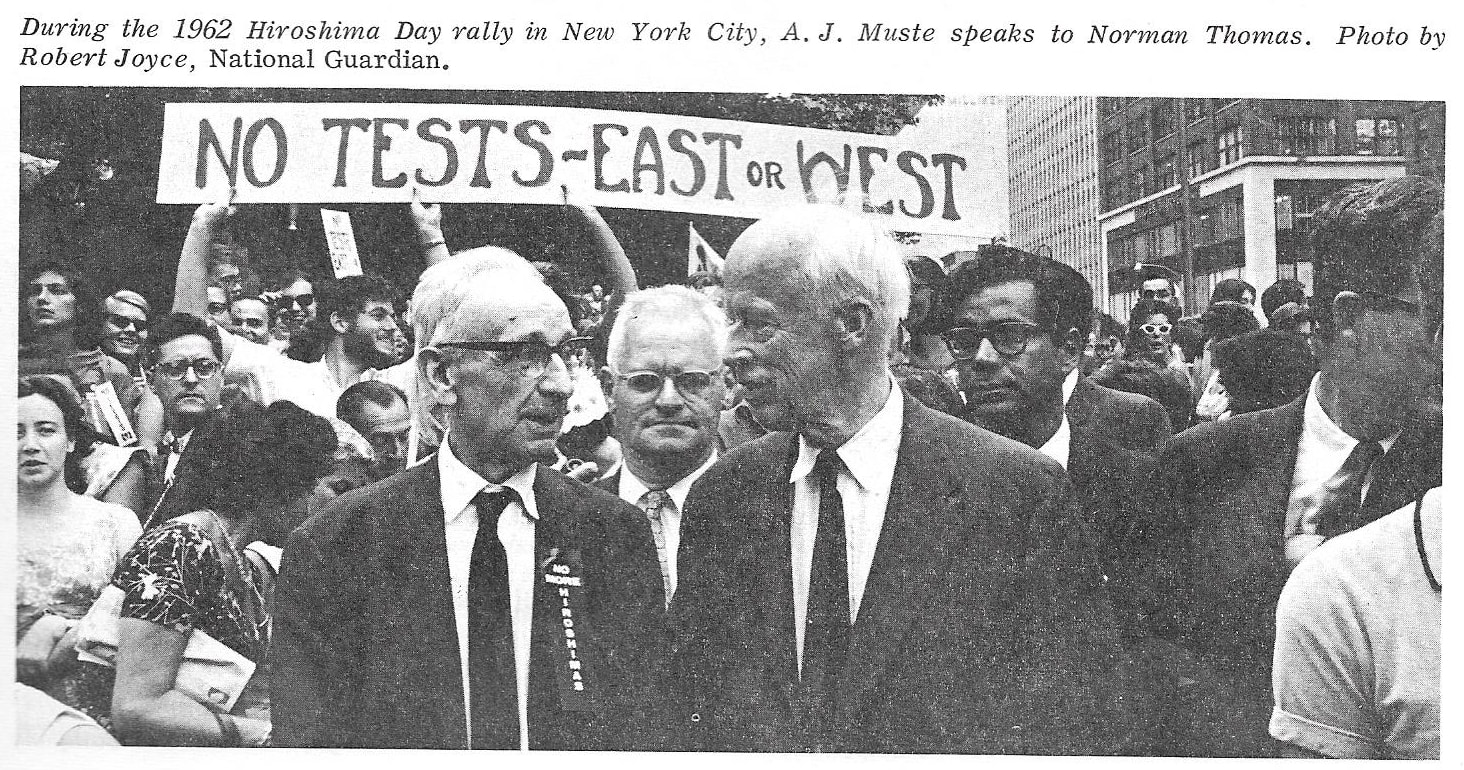

Muste took additional classes in philosophy and theology during and after his time at New Brunswick Theological Seminary. While attending lectures by William James in New York City, Muste met the great progressive theorist John Dewey. The two became good friends. Muste became influenced by Dewey’s theory of pragmatism: that learning and deep understanding is best achieved through direct experience. This was also the time in which Muste became more interested in the “Social Gospel” movement as well as other progressive and left ideas. He left his pastorship and the Dutch Reformed Church in 1914 over its conservatism, but joined the radical Christian-oriented Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) shortly after its founding in 1916. He resigned again from another pastor position over his pacifism in 1917, as the United States entered the First World War. For a time, Muste worked for the ACLU aiding conscientious objectors. Then, in 1919, A.J. Muste got involved with Lawrence Textile Strike. We have told the story of the 1919 Lawrence Textile Strike before (https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/permalink/10158108528137978/). Almost all outside support for the strike came from the Boston Comradeship, a group of radical pastors which Muste helped found. And so, after a week of picketing and violence, the workers asked Muste to organize and lead them. For the next 16 weeks, Muste personally led a nonviolent strike even as the police became more aggressive, winning public support and ultimately forcing the factory owners to accept most of the workers’ demands. Following this strike, Muste became more involved in the workers movement and socialist politics. For the next 17 years after the 1919 Lawrence Textile Strike, Muste worked on organizing unions, pushing dominant unions like the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to the left, and proving the practicality of nonviolent strikes. Among some of the strikes Muste led include the 1936 Goodyear Tire Strike in Akron, which is the first recorded use of the sit-down technique in a modern civil disobedience action. He became a Marxist-Leninist, a revolutionary, and became convinced of the need for an American labor party. Not all of his endeavors were successful. For two years after his first strike, Muste tried and failed to organize the Amalgamated Textile Workers of America. He had to leave his positions at both religious and secular organizations due to his politics numerous times. He even had to leave his director position at the Brookwood Labor College -- a school to learn labor theory and militancy -- in 1933 due to controversy over his activism. In 1929, Muste helped found the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA), from which the American Workers Party (AWP) was born. Muste’s sharp and effective organizing skills became so deeply associated with the AWP that many contemporaries called the group “Musteites.” Within a few years, the Musteites would merge with the Trotskyist Communist League of America to form the Workers Party of the United States (WPUS). Under the new organization, however, Muste started to become disillusioned with the efficacy of socialist politics, and began to consider leaving the Trotskyist movement. It was 1936 when Muste took a vacation and met the man himself, Leon Trotsky, in exile in Sweden. Muste was impressed, even captivated by Trotsky, but was ultimately unconvinced by the great revolutionary to stay within the movement. By the time Muste had returned to the United States, Muste had decided to retry the revolutionary Christian pacifist path, but now with all that had learned in the labor movement. He would stay that course for the rest of his life. But for Muste, leaving a college, a church, a political party, or a movement did not mean having to burn bridges. He served as the executive director of FOR from 1940-1953. He joined the national committee of the War Resisters League. He became a close friend and ally of Dorothy Day, one of the founders of the direct-actionist Catholic Worker Movement. He mentored the great civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin, who claimed that he never made a difficult decision before discussing it with Muste first. He organized for years against US nuclear weapons policies. He led opposition to US involvement in the Vietnam War, even traveling there with the Committee for Nonviolent Action in 1966. But even as Muste made more connections with new people all the time, he also kept in touch with his past allies: even the communists during the height of McCarthyism, when so many other allies abandoned them. He was trusted by anarchists and pacifists, housewives and union guys, New Left youth and old school socialists. His integrity was legendary. A year after his death in 1967, the War Resisters League began to rent the building at 339 Lafayette Street in Manhattan; they bought the building in 1974 before selling it to the A.J. Muste Institute four years later. From 1978 to 2015, 339 Lafayette Street was known as the “Peace Pentagon” for the number of social justice organizations that were headquartered there, including the War Resisters League, the Socialist Party USA, the Metropolitan Council on Housing, the Catholic Peace Fellowship, Political Art Documentation/Distribution, and more. For decades after his death, the leftists, pacifists, and progressives inspired by A.J. Muste’s example continued to work, if not side-by-side, then under the same roof: a fitting legacy for a person who directly and indirectly affected so many lives. Sources: Danielson, Leilah. American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014. Reyes, Gwen, editor. “WIN: Peace & Freedom Through Nonviolent Action.” 1967. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed