|

Latinx Heritage Month runs from September 15 to October 15. In Connecticut, more than half of our Latinx population is Puerto Rican, and we are home to the sixth largest Puerto Rican population in the fifty states. No state has a higher percentage of Puerto Ricans in their total population than Connecticut — roughly one out of every twelve CT residents (8.5%) can claim Puerto Rican heritage as of 2020. Due to the strong connections between so many Connecticut residents and Puerto Rico, this week we examine the story of the successful campaign at Culebra won by a coalition of Puerto Rican and mainland American activists including New England Committee for Nonviolent Action members (CNVA, predecessors of VPT).

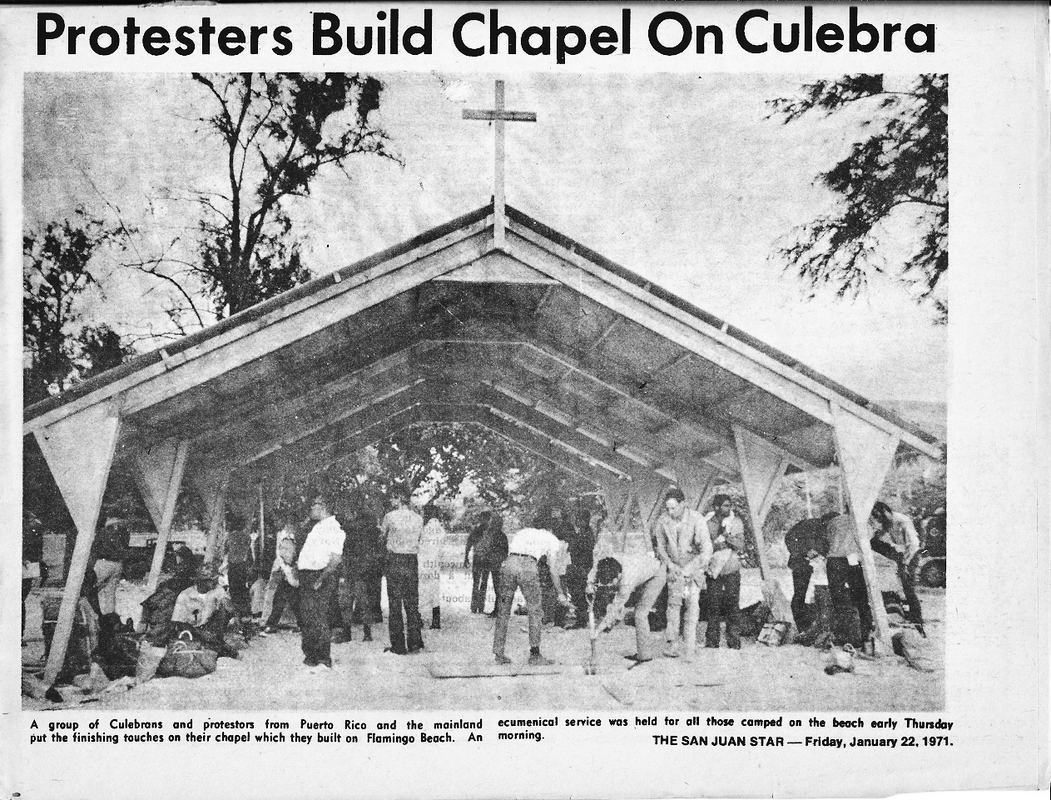

[Read The Recolonization of Puerto Rico, Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2012501098900215] The relationship between Puerto Ricans and mainland Americans was in part responsible for building up the campaign that successfully ousted the US Navy from the Puerto Rican island of Culebra in the early 1970s. Local resistance to the US Navy takeover of Culebra Island in Puerto Rico began shortly after the United States recolonized the nation from the Spanish Empire in 1898, but in the aftermath of the rapid US invasion, the Culebrans alone could not keep the US Navy out. Instead, the US Navy evicted all of the residents of the biggest town on the island, leveled the town, and built a naval base upon the ruin. By the time the United States joined WWII, the federal government claimed exclusive rights to the air space of Culebra as far out as 3 miles from the coastline, and had sights on converting the entire 10 square mile island into a military base. By 1950 the US Navy controlled ⅓ of the island, the civilian population had dropped from 4000 residents in 1900 to just 580 residents, and the small island was covered in bomb craters. Decades of live training exercises and weapons tests littered the island and surrounding waters with unexploded bombs, heavy metals, and other toxic chemicals. In the early 1950s, the US Navy attempted to evict the remainder of Culebra’s civilian residents, but was blocked by the Puerto Rican government on constitutional grounds. Less than two decades later in 1970, the US Navy attempted the mass eviction again, but this time they faced intense popular opposition and unwanted scrutiny by the press both in Puerto Rico and on the US mainland. As local Culebrans began to stage public demonstrations and nonviolent direct actions against the US Navy, a diverse coalition of allies began to form on both sides of the Caribbean: the Puerto Rican Senate urged President Nixon to reconsider the US military’s plans, the Puerto Rican Independence Party occupied San Juan naval base with 600 protesters for three days, and groups like the Rescue Culebra Committee (RCC) and the Clergy Committee to Rescue Culebra (CCRC) formed to coordinate support from the US mainland. One mainland ally organization, A Quaker Action Group (AQAG), originally formed in 1966 to “apply nonviolent direct action as a witness against the war in Vietnam” and soon found themselves involved in the Culebra campaign as an extension of their antiwar work. Several CNVA members participated in the campaign under the AQAG banner including New England CNVA cofounder Bob Swann. Many of these allies from the US mainland went to Culebra to join direct action efforts there. In January 1971, the Puerto Rican protesters and their allies from RCC, CCRC, and AQAG gathered on Flamingo Beach, a US Navy bombing range. As a former home builder for Frank Lloyd Wright, Bob Swann volunteered his skills for an ambitious project: to design and build a chapel on the beach over the site of an older church that the military had previously destroyed, all while being monitored and blockaded by the US Navy. They completed the chapel after just three days and AQAG members led worship services to disrupt Operation Springboard, a massive military training exercise involving eight countries. When US Marines deployed tear gas against the protesters, demolished the new chapel, and had over a dozen people arrested and jailed (including Puerto Rican Independence Party President Rubén Ángel Berríos Martínez), students at the University of Puerto Rico rebelled and joined 1000 other allies to protest the sentencing and hold daily vigils at the jail. Soon after the arrests were made, the US Navy agreed to relocate to another island by 1975 with the signing of the Culebra Agreement. Within a year, however, the US military’s duplicity was revealed when US Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird voiced intentions to keep using the military base on the island until at least 1985, if not indefinitely. The revelation was an insult to Puerto Ricans all over and sparked even more protests in Puerto Rico and the mainland US. Activists on the mainland built replicas of the demolished chapel in front of the Pentagon and several of the embassies of nations involved in Operation Springboard. In Puerto Rico, rival political parties united to oppose the US Navy’s true plans for Culebra. On the island of Culebra itself, someone put a cross on the fence blocking protesters from the original chapel location with the slogan “You tore down a chapel but you can’t destroy the spirit that builds it ever again.” Due to the sustained pressure on the US Navy from all sides in Puerto Rico and in D.C., President Richard Nixon finally declared in 1974 that the federal government would comply with the original Culebra Agreement and cease all military operations on the island by the end of 1975. While the US government’s clean-up of the toxic chemicals and unexploded ordnance on Culebra has been extremely slow, and while it is also true that the US military simply moved their Culebra operations to Vieques, another small Puerto Rican island, the success at Culebra proved to Puerto Ricans all over that they could successfully organize themselves to challenge their colonizers. Primarily using nonviolent direct action and the strategic use of ally groups, the Culebra campaign kicked out the most powerful military in the world. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Balderston, Daniel. “Culebra Action 1971.” [PDF]. https://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/20357/1/Culebra_Action_1971.pdf “Puerto Ricans expel United States Navy from Culebra Island, 1970-1974.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. [Accessed 28 September 2021]. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/puerto-ricans-expel-united-states-navy-culebra-island-1970-1974 Swann, Marj. “Culebra Action.” Direct Action for a Nonviolent World. 17 Feb. 1971. How much damage could a modern nuclear weapon cause in southeastern Connecticut? How far would the damage spread, and for how long could it last? How likely is a firestorm to develop, how is it different from a regular forest fire, and how big could it get? If the bomb goes off close to the shoreline, I’d be okay up in Willimantic, right? I mean, how bad could it really be?

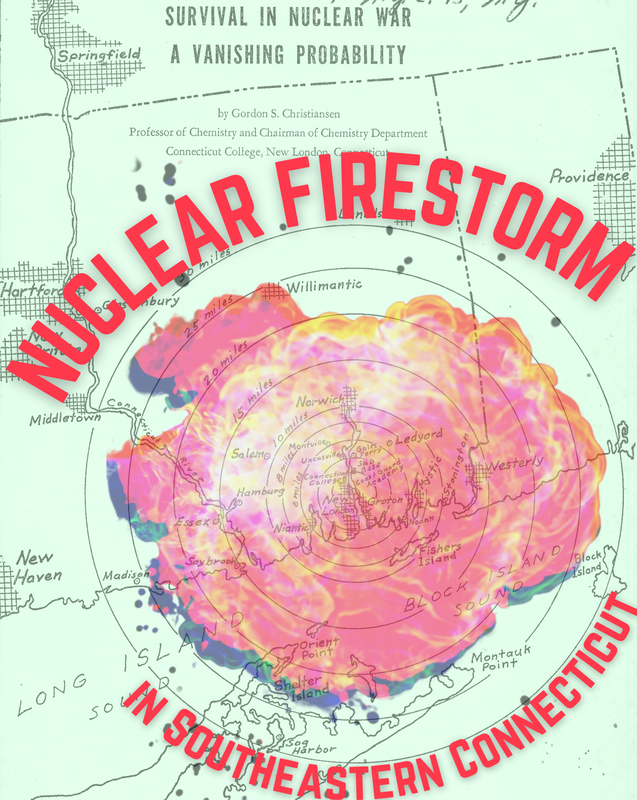

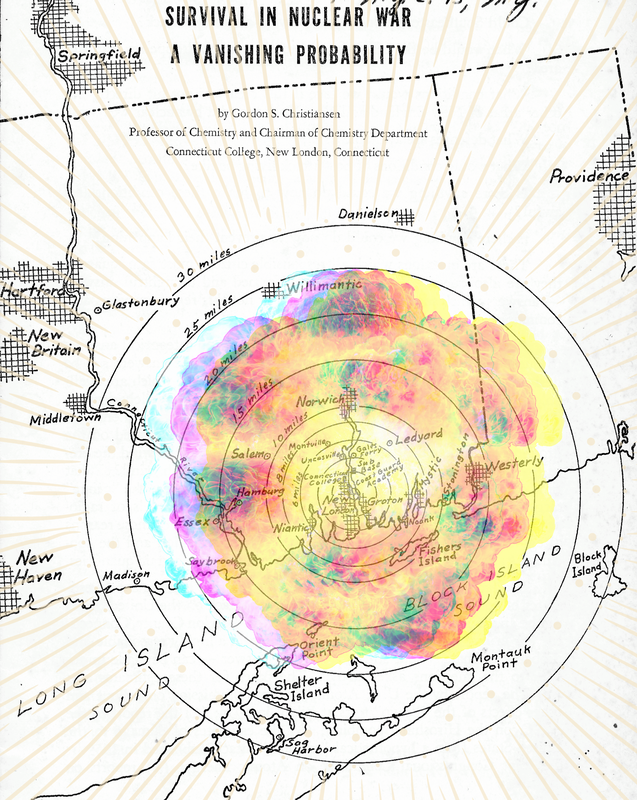

Professor Gordon S. Christiansen, chairman of the Connecticut College Chemistry Department in the 1960s, addressed these questions in this week’s excerpts from his 1960 pamphlet Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. The first two excerpts regarded the effects of a Hiroshima-size atomic bomb detonated over the New London - Groton bridge: the initial blast, firestorms, and radiation. Excerpts #3 & 4 explore the same scenario but with a much more powerful “modern” thermonuclear weapon. Today’s excerpt finishes the second scenario with a brief discussion on the devastating firestorm that would rip through the entire region. (Read Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2029219227228402) (Read Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2040482629435395) (Read Part 3 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2046153552201636) (Read Part 4 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2057147997768858) In all previous excerpts, the catastrophic scenarios described were the results of single bombs of different sizes detonated over the New London - Groton bridge. In the final two excerpts after this one, the topic will turn to the more likely scenario of a general widespread nuclear attack on the New York - New England region — and what effects such an attack would have on southeastern Connecticut. On Tuesday, people around the world celebrated the UN International Day of Peace. The theme this year was “recovering better for a sustainable and equitable world.” Earlier this year, the UN marked an even more impactful moment: the coming into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which made nuclear weapons illegal under international law. As we read the frightening scenario presented by Professor Christiansen, let us consider the barrier to international peace that the United States nuclear arsenal poses, how the mere existence of the arsenal encourages rival powerful governments to build their own nuclear weapons, the fact that the United States is the only government to ever use these weapons in war, and thus our special responsibility to dismantle our nuclear weapons immediately. A sustainable and equitable world cannot be recovered while we keep weapons of such destructive power in our holsters. — After describing the effects of radiation it is almost too much to turn now to the effects of the fire which would be an inevitable result of this hypothetical nuclear incident in Southeastern Connecticut. But the searing heat and the attendant fire store are facts of nuclear war and any serious appraisal of this incident must consider them. The detonation of the bomb takes place in less than a millionth of a second. During that time the materials of the bomb itself and all substances near it, the earth, water, steel, concrete, are vaporized, then are heated to temperatures in excess of a hundred million degrees and are compressed to many billions of pounds pressure. A huge fire ball develops, increasing in size quickly to two miles across and rising at a rate of 300 miles per hour to a height of 25 or 30 miles. There are two pulses of heat radiation, the first lasting only a fraction of a second, the second reaching a maximum in a few seconds but lasting for half a minute or more. If our hypothetical man in Willimantic had looked at this fire ball [in New London], he would have had a very brief impression of something many hundreds of times brighter than the noon sun — then he would have been blinded permanently; his exposed flesh would have been charred; his clothing would have been burned off him. His frame house would burst into flame; his lawn, shrubs and trees would take fire; his asphalt driveway would melt. The range of third degree burns to exposed people would be 25 to 30 miles out from this bomb. This would also mark the edge of the fire storm, in principle like the one described for the small, old fashioned atomic bomb but vastly greater and more devastating. The wooded areas of Southeastern Connecticut and Southern Rhode Island, extending from the Connecticut River almost to Narragansett Bay and north almost to Glastonbury and Danielson, would form one huge fire raging through the whole area, swept toward the center by 200 mile an hour winds. This fire would be many orders of magnitude greater than any ordinary forest fire. It is almost certain that it would only be extinguished by ultimately consuming all combustible material in its path. There would be some light rainfall along with the fallout during the early stages of the fire storm. But this would be ineffectual in controlling the fire and would also bring more unpleasant and dangerous material down with it. An example of such noxious secondary products of the bomb which would fall over the devastated area is the 120,000 tons of nitric acid which the nuclear explosion forms from the nitrogen and oxygen of the air. It is possible that many people in the outlying areas might survive this combination of assaults on human life. But any attempt at prediction of numbers would be meaningless. Geographic location, precautionary measures, and intelligent understanding of the nature and timing of the threats would be important factors in determining individual survival. But the most important factor of all would be plain luck. If a particular unique set of circumstances prevailed so that the blast, the initial flash of heat, direct radiation, flying objects, falling buildings, fallout radiation, and ingested radioactivity were all avoided, then the lucky person might survive to deal with the untold almost unimaginable, exigencies of the post-attack period. But if any single one of the primary threats could not be avoided then post-attack living would be a problem. — Take Action If you are concerned about nuclear weapons and live in Connecticut, consider joining the CT Committee on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Committee organizes demonstrations against nuclear weapons throughout the year. Sign up to the mailing list here: https://forms.gle/pX8v2U4CktAcz8s78 You can also sign petitions to pressure our government to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, like this one: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/support-the-nuclear-weapons-ban-treaty — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Christiansen, Gordon S. Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Connecticut College, 1961. — Further Resources “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ How much radiation does a nuclear detonation emit? How far does it span, and how long does it last? How quickly can radiation kill me after a nuclear explosion? These are the questions Professor Gordon S. Christiansen, chairman of the Connecticut College Chemistry Department in the 1960s, sought to answer in the following excerpt from his 1960 pamphlet Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Previous excerpts have dealt with the force of the initial blast, the potential for a firestorm to develop, and some of the effects or radiation.

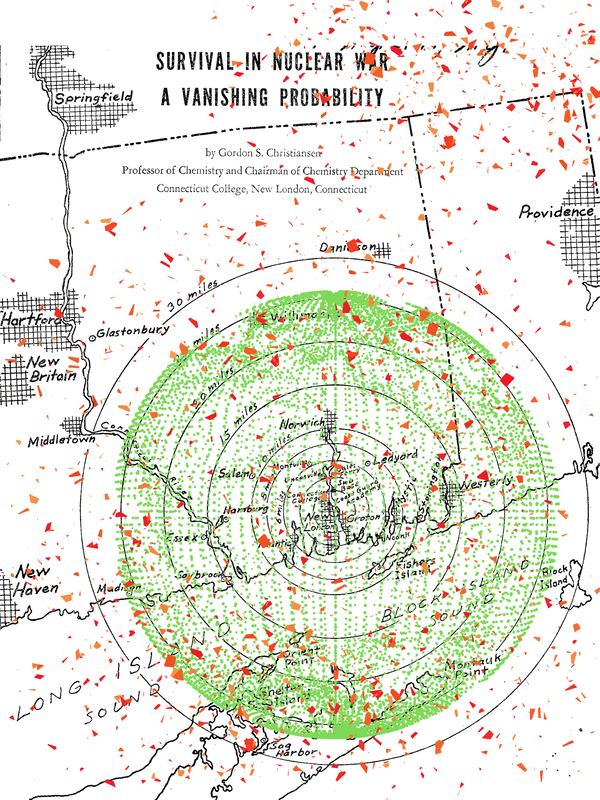

(Read Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2029219227228402) (Read Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2040482629435395) (Read Part 3 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2046153552201636) This excerpt continues the examination of radiation from a hypothetical nuclear blast over the bridge that connects New London and Groton, especially the shockingly brief amount of time one has to be exposed to radiation to receive a lethal dose, as well as the enormous geographical extent over which the radiation would spread. Because of the inevitability of these weapons eventually being used in war, and because of the unconscionably horrifying amounts and types of destruction these weapons cause, on January 22, 2021, the United Nations’ Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force. In honor of all of the victims of nuclear weapons, and with great hope in the new international treaty, we present Professor Christiansen’s Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability, part 4. — Again, the truly awesome destructive effects of radiation are shown by the fallout from the bomb. The energy released by large nuclear weapons is divided among three major effects; somewhat over a third appears as blast, a third as heat, and less than a third appears as radioactivity. Nearly half of this radioactivity will be carried by the huge mushroom cloud into the stratosphere and will be more or less equally distributed over the whole earth. Much of the radioactivity of this worldwide fallout will be lost while it is remotely high up; the remainder will be so evenly distributed over the surface of the earth that it is of no concern in the local crisis. The most damaging effect is caused by the so called “local” fallout, that which falls within several hours of the detonation and within a couple of hundred miles of the center of the burst. This local fallout is distributed in two patterns. The major one is a long elliptical area up to 250 miles long and about 40-50 miles wide, with the long dimension in the direction of the prevailing winds. From our hypothetical bomb dropped on the Thames river bridge a deadly wave of fallout would sweep to the northeast. Providence — and the whole state of Rhode Island — would be covered within two hours; Boston and all of Massachusetts between there and Cape Cod would be covered within four hours after the detonation here. Over half of this huge elliptical pattern of “local” fallout would fall harmlessly into Massachusetts Bay and the Gulf of Maine — harmless that is, except that the fish and other sea life in this area would become too radioactive to eat for several months after the incident. The second pattern of local fallout from this bomb would be of much more concern to us in Southeastern Connecticut. This pattern is roughly circular, about 25 miles in radius; it would start at Madison on the coast, include most of Middlesex County, just miss Middletown, include Willimantic to the north and the southwestern third of Rhode Island to the east; it would just miss Block Island and include the tip of Long Island as far back as Sag Harbor. Within this area large particles of fallout would rain down almost immediately after the bomb detonation; within an hour the whole area would be covered by a deep layer of wildly radioactive dust. It is not possible accurately to predict the level of this radioactivity within the area close to the bomb site. The most pertinent estimate is one made by the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory. This institution has made the most detailed studies of actual fallout levels in the Pacific bomb tests and on the basis of these actual measurements has estimated the average level of fallout radioactivity over the whole land surface of the United States which would result from the explosion of 263 hydrogen weapons on strategic and population targets scattered throughout the country. On the basis of their estimates the average level of fallout radioactivity would be 7500 roentgens per hour at the end of the first hour. Since there are sizeable areas which would have no fallout at all, clearly some areas would have levels of radioactivity inordinately higher than the average and certainly among these would be the area immediately surrounding a big bomb drop. An extremely conservative estimate would be that the 25 mile circle around New London would have an initial (end of the first hour) level of radioactivity of 20,000 roentgens per hour (roughly three times the average); the level in the elliptical pattern would be much lower than this, probably less than twice the Naval Laboratory Radiological Laboratory estimate of average radioactivity. A dose of radiation between 300 and 500 roentgens has a 50% probability of being fatal; a dose of around 700 to 900 roentgens is always fatal. Thus anyone exposed to the fallout within the 25 mile circle for as long as two minutes during the first hour would certainly die of radiation damage; in Providence the fatal exposure would be 10 to 20 minutes during the second hour. Further consideration of the damaging effects of the fallout radiation and the possibility of protection against it must take cognizance of three factors. The first is that the level of radioactivity decreases rapidly with time because of the natural decay of the radioactive materials[...] Thus, at the end of seven hours the level of radioactivity in Southeastern Connecticut would be about 2000 roentgens per hours[...] At the end of two days the level at the fringes would be about 200 roentgens per hour; at the end of two weeks it would be 20; in four months it would be 2 roentgens per hour. The second factor to consider is the protection offered by various structures or shelters. An automobile or the first floor of an ordinary home offers a protection factor of about 2. That is, a person in (or under) an automobile or inside a house would receive only half the radiation he would in the open. In the basement of a house the factor would be between 10 and 100; the best basement shelter recommended by OCDM has a protection factor of about 1000; a self contained deep blast shelter would decrease the radioactivity by several thousand. The third factor to consider is that harmful effects of radiation are cumulative. That is, if a person in Willimantic say, heard the explosion in New London and came out in the open to see what it was and stayed out long enough to be exposed to radioactive fallout for 30 seconds, he would have received about 150 roentgens. If he then went inside and took another 30 seconds to pick up his portable radio, he would have received another 75 roentgens. If he then went immediately to a near perfect deep blast shelter and stayed there from then on, he would still be in danger of dying from radiological exposure[...] The chances of survival for people further out from the bomb blast would be much better; but those closer in would have much less chance. Also it is quite clear that the first minute, the first hour, the first day are the times when protection is most effective. If a person is inside an adequate shelter at the time of detonation and has an adequate supply of uncontaminated air, food, and water and sanitation facilities to hold out in a deep shelter for the first few weeks, he can then safely stand brief periods of exposure to the unshielded radiation from fallout. — Take Action If you are concerned about nuclear weapons and live in Connecticut, consider joining the CT Committee on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Committee organizes demonstrations against nuclear weapons throughout the year. Sign up to the mailing list here: https://forms.gle/pX8v2U4CktAcz8s78 You can also sign petitions to pressure our government to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, like this one: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/support-the-nuclear-weapons-ban-treaty — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Christiansen, Gordon S. Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Connecticut College, 1961. — Further Resources “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ On 9/11, longtime War Resisters League staff person David McReynolds, who had been active with the Committee for Nonviolent Action, wrote this from the WRL National Office AKA the “Peace Pentagon” which was only a mile and half north of the World Trade Towers. While we emphatically denounce all attacks on civilians and other forms of terrorism, these excerpts are also a painful and perceptive reminder of the United States’ central role in the proliferation of violence around the world and that war is never the answer.

As we write, Manhattan feels under siege, with all bridges, tunnels, and subways closed, and tens of thousands of people walking slowly north from Lower Manhattan. As we sit in our offices here at War Resisters League, our most immediate thoughts are of the hundreds if not thousands of New Yorkers who have lost their lives in the collapse of the World Trade Center. The day is clear, the sky is blue, but vast clouds billow over the ruins where so many have died, including a great many rescue workers. In this piece that later became a Statement from the War Resisters League, they also recognized the deaths of innocent passengers in the other planes and that “We do not know at this time from what source the attack came.” But as an organization that believes that war is a crime against humanity, there was not a confusion about what was happening that included a prescient reminder about the prior U.S role in Afghanistan. The policies of militarism pursued by the United States have resulted in millions of deaths, from the historic tragedy of the Indochina war, through funding of death squads in Central America and Colombia, to the sanctions and air strikes against Iraq. This nation is the largest supplier of “conventional weapons” in the world - and those weapons fuel the starkest kind of terrorism from Indonesia to Africa. The early policy support for armed resistance in Afghanistan resulted in the victory of the Taliban - and the creation of Osama Bin Laden. And what do we do? The answer is the same now that it was 20 years ago: Let us seek an end of the militarism that has characterized this nation for decades. Let us seek a world in which security is gained through disarmament, international cooperation, and social justice not through escalation and retaliation. We condemn without reservations attacks such as those which occurred today, which strike at thousands of civilians - may these profound tragedies remind us of the impact U.S. policies have had on other civilians in other lands. We also condemn reflexive hostility against people of Arab descent in this country and urge that Americans recall the part of our heritage that exposes bigotry in all forms. We are one world. We shall live in a state of fear and terror or we shall move toward a future in which we seek peaceful alternatives to violence, and a more just distribution of the world’s resources. — Photo credit: Michelle Williams, “Union Square Memorial 7,” https://mlwms.com/9-11/ What would happen if a Hiroshima-size atomic bomb detonated in New London? Several weeks ago, we began to give the details of that hypothetical scenario as outlined in a pamphlet made by Professor Gordon S. Christiansen, chairman of the Connecticut College Chemistry Department in the 1960s, who became involved with the Committee for Nonviolent Action (VPT’s predecessor) due to his nuclear concerns. Last week, we finished that scenario with details about the likely firestorm and the extent of destruction caused by such a detonation. That first scenario described by Professor Christiansen would result in unimaginably intense destruction and loss of life, but would also allow the possibility for societal recovery and rebuilding.

(Read Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2029219227228402) (Read Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2040482629435395) Unfortunately, our modern nuclear weapons today are much more powerful than the first-generation weapons the United States used on Japan in 1945. In the pamphlet, Professor Christiansen goes on to describe what would result from the detonation of a “modern” (in 1960) 20 megaton nuclear weapon in New London starting with the initial blast, the mile-wide crater it would leave behind, and the damage to buildings and infrastructure out as far as 100 miles from the blast. Rarely do we have the opportunity to read a well-researched description of the effects of a nuclear detonation specifically on our own community. Due to rising tensions and the uncertain state of nuclear weapons in our world today, on January 22, 2021, the United Nations’ Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force, making the production, possession, and use of nuclear weapons to be an international crime. In honor of all of the victims of nuclear weapons, and with great hope in the new international treaty, we present Professor Christiansen’s Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability, part 3. — The possibility of recreating a community life in this area after a general nuclear attack is, to put it as mildly as possible, much less promising. But it will be more meaningful to consider such possibilities after examining the effects of modern nuclear weapons on this area. The effects of a nominal 20 megaton nuclear weapon (24 million tons of TNT explosive equivalent) have been determined by several actual tests of such weapons. A bomb of this size is over a thousand times as powerful as the Hiroshima type weapon and causes correspondingly greater damage. If such a weapon were to explode at ground level near the Groton-New London bridge, it would leave a crater about a mile across and 300 feet deep. This huge hole and the sizeable circular hill of earth and radioactive debris which would surround it would cover what was once the downtown New London and Groton areas. The sites of the present State pier, the railroads yards, Winthrop school, and the State Police barracks would be from 100 to 200 feet down the slope into the crater. The Coast Guard Academy, downtown New London and Groton, and the Electric Boat factory would be buried under the lip of the crater formed by the fall-back of the nuclear excavation. The area of total destruction, even of the most heavily reinforced concrete structures, would extend out about four miles. This circle includes Ocean Beach, Jordan Village, all of Quaker Hill and Connecticut College, all of the Submarine Base, all of the housing near the Sub Base, Poquonock Bridge, and Trumbull airport. In this area there would literally not be a stone in place. Streets, building sites and other landmarks would be obliterated in a tangled mass of wreckage; even deep blast shelters would be destroyed. No human being in this area would survive even the instantaneous blast. Out to an area of six miles radius, which includes Niantic, Flanders, Montville, Uncasville, Gales Ferry, much of Ledyard, Mystic, and Noank, all brick buildings, even those with few windows and heavy construction would be totally destroyed and with them any basement shelters under them. Also in this area the blast would cause severe lung damage leading to virtual total casualties from this cause alone. At a radius of ten miles there would be total destruction of all frame buildings, damage beyond repair to all brick buildings, and serious (though partially repairable) damage to reinforced concrete structures. On the fringes of this area (beyond about 8 miles), which includes all of the towns of East Lyme, Waterford, Montville, Ledyard, New London, Groton, and the outskirts of Norwich, half of the town of Stonington (including the Village) and all of Fishers Island, deep blast shelters would be effective protection but basement fallout shelters would be of no use. At a radius of 15 miles (a circle beginning at the town of Saybrook, touching Essex and Hamburg, including all of the town of Salem, all of Bozrah, going well beyond Norwichtown and Taftville, including all of the towns of Preston and North Stonington, the city of Westerly, Rhode Island, and the whole Watch Hill area) all frame buildings buildings would be damaged beyond repair and any basement shelters under them would be badly compromised. Brick buildings would be severely damaged but generally repairable. In this area much damage would be done by flying objects, not the least of which would be people. AEC [Atomic Energy Commission] tests which have included dummies resembling human bodies left in the open have shown that a very serious cause of casualties will be flying human bodies, thrown through the air by the initial blast effect. Minor damage to houses and other construction, such as broken windows, falling plaster, and cracked walls, will extend out from the center over 100 miles. The area of instantaneous killing radiation, intense enough to penetrate more than two feet of concrete or earth, will extend out from the center to a radius of two and a half miles, including all of New London, the Cohanzie and Quaker Hill sections of Waterford, Connecticut College, all of the Submarine Base, and all of the town of Groton as far away as Poquonock Bridge. But in this area total killing by radiation is simply added to total killing by blast. Again, the truly awesome destructive effects of radiation are shown by the fallout from the bomb. The energy released by large nuclear weapons is divided among three major effects; somewhat over a third appears as blast, a third as heat, and less than a third appears as radioactivity. Nearly half of this radioactivity will be carried by the huge mushroom cloud into the stratosphere and will be more or less equally distributed over the whole earth. Much of the radioactivity of this worldwide fallout will be lost while it is remotely high up; the remainder will be so evenly distributed over the surface of the earth that it is of no concern in the local crisis. The most damaging effect is caused by the so called “local” fallout, that which falls within several hours of the detonation and within a couple of hundred miles of the center of the burst… — Take Action If you are concerned about nuclear weapons and live in Connecticut, consider joining the CT Committee on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Committee organizes demonstrations against nuclear weapons throughout the year. Sign up to the mailing list here: https://forms.gle/pX8v2U4CktAcz8s78 You can also sign petitions to pressure our government to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, like this one: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/support-the-nuclear-weapons-ban-treaty — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Christiansen, Gordon S. Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Connecticut College, 1961. — Further Resources “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed