|

How much radiation does a nuclear detonation emit? How far does it span, and how long does it last? How quickly can radiation kill me after a nuclear explosion? These are the questions Professor Gordon S. Christiansen, chairman of the Connecticut College Chemistry Department in the 1960s, sought to answer in the following excerpt from his 1960 pamphlet Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Previous excerpts have dealt with the force of the initial blast, the potential for a firestorm to develop, and some of the effects or radiation.

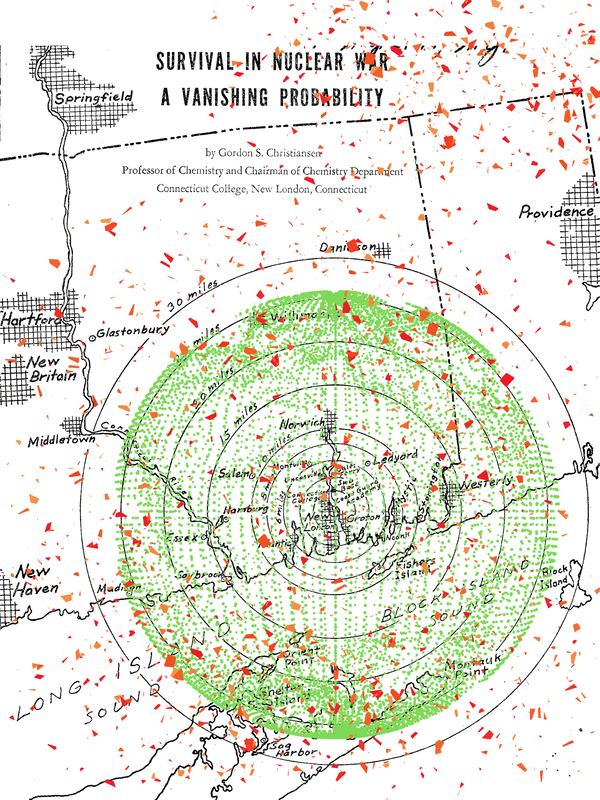

(Read Part 1 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2029219227228402) (Read Part 2 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2040482629435395) (Read Part 3 here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/2046153552201636) This excerpt continues the examination of radiation from a hypothetical nuclear blast over the bridge that connects New London and Groton, especially the shockingly brief amount of time one has to be exposed to radiation to receive a lethal dose, as well as the enormous geographical extent over which the radiation would spread. Because of the inevitability of these weapons eventually being used in war, and because of the unconscionably horrifying amounts and types of destruction these weapons cause, on January 22, 2021, the United Nations’ Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force. In honor of all of the victims of nuclear weapons, and with great hope in the new international treaty, we present Professor Christiansen’s Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability, part 4. — Again, the truly awesome destructive effects of radiation are shown by the fallout from the bomb. The energy released by large nuclear weapons is divided among three major effects; somewhat over a third appears as blast, a third as heat, and less than a third appears as radioactivity. Nearly half of this radioactivity will be carried by the huge mushroom cloud into the stratosphere and will be more or less equally distributed over the whole earth. Much of the radioactivity of this worldwide fallout will be lost while it is remotely high up; the remainder will be so evenly distributed over the surface of the earth that it is of no concern in the local crisis. The most damaging effect is caused by the so called “local” fallout, that which falls within several hours of the detonation and within a couple of hundred miles of the center of the burst. This local fallout is distributed in two patterns. The major one is a long elliptical area up to 250 miles long and about 40-50 miles wide, with the long dimension in the direction of the prevailing winds. From our hypothetical bomb dropped on the Thames river bridge a deadly wave of fallout would sweep to the northeast. Providence — and the whole state of Rhode Island — would be covered within two hours; Boston and all of Massachusetts between there and Cape Cod would be covered within four hours after the detonation here. Over half of this huge elliptical pattern of “local” fallout would fall harmlessly into Massachusetts Bay and the Gulf of Maine — harmless that is, except that the fish and other sea life in this area would become too radioactive to eat for several months after the incident. The second pattern of local fallout from this bomb would be of much more concern to us in Southeastern Connecticut. This pattern is roughly circular, about 25 miles in radius; it would start at Madison on the coast, include most of Middlesex County, just miss Middletown, include Willimantic to the north and the southwestern third of Rhode Island to the east; it would just miss Block Island and include the tip of Long Island as far back as Sag Harbor. Within this area large particles of fallout would rain down almost immediately after the bomb detonation; within an hour the whole area would be covered by a deep layer of wildly radioactive dust. It is not possible accurately to predict the level of this radioactivity within the area close to the bomb site. The most pertinent estimate is one made by the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory. This institution has made the most detailed studies of actual fallout levels in the Pacific bomb tests and on the basis of these actual measurements has estimated the average level of fallout radioactivity over the whole land surface of the United States which would result from the explosion of 263 hydrogen weapons on strategic and population targets scattered throughout the country. On the basis of their estimates the average level of fallout radioactivity would be 7500 roentgens per hour at the end of the first hour. Since there are sizeable areas which would have no fallout at all, clearly some areas would have levels of radioactivity inordinately higher than the average and certainly among these would be the area immediately surrounding a big bomb drop. An extremely conservative estimate would be that the 25 mile circle around New London would have an initial (end of the first hour) level of radioactivity of 20,000 roentgens per hour (roughly three times the average); the level in the elliptical pattern would be much lower than this, probably less than twice the Naval Laboratory Radiological Laboratory estimate of average radioactivity. A dose of radiation between 300 and 500 roentgens has a 50% probability of being fatal; a dose of around 700 to 900 roentgens is always fatal. Thus anyone exposed to the fallout within the 25 mile circle for as long as two minutes during the first hour would certainly die of radiation damage; in Providence the fatal exposure would be 10 to 20 minutes during the second hour. Further consideration of the damaging effects of the fallout radiation and the possibility of protection against it must take cognizance of three factors. The first is that the level of radioactivity decreases rapidly with time because of the natural decay of the radioactive materials[...] Thus, at the end of seven hours the level of radioactivity in Southeastern Connecticut would be about 2000 roentgens per hours[...] At the end of two days the level at the fringes would be about 200 roentgens per hour; at the end of two weeks it would be 20; in four months it would be 2 roentgens per hour. The second factor to consider is the protection offered by various structures or shelters. An automobile or the first floor of an ordinary home offers a protection factor of about 2. That is, a person in (or under) an automobile or inside a house would receive only half the radiation he would in the open. In the basement of a house the factor would be between 10 and 100; the best basement shelter recommended by OCDM has a protection factor of about 1000; a self contained deep blast shelter would decrease the radioactivity by several thousand. The third factor to consider is that harmful effects of radiation are cumulative. That is, if a person in Willimantic say, heard the explosion in New London and came out in the open to see what it was and stayed out long enough to be exposed to radioactive fallout for 30 seconds, he would have received about 150 roentgens. If he then went inside and took another 30 seconds to pick up his portable radio, he would have received another 75 roentgens. If he then went immediately to a near perfect deep blast shelter and stayed there from then on, he would still be in danger of dying from radiological exposure[...] The chances of survival for people further out from the bomb blast would be much better; but those closer in would have much less chance. Also it is quite clear that the first minute, the first hour, the first day are the times when protection is most effective. If a person is inside an adequate shelter at the time of detonation and has an adequate supply of uncontaminated air, food, and water and sanitation facilities to hold out in a deep shelter for the first few weeks, he can then safely stand brief periods of exposure to the unshielded radiation from fallout. — Take Action If you are concerned about nuclear weapons and live in Connecticut, consider joining the CT Committee on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Committee organizes demonstrations against nuclear weapons throughout the year. Sign up to the mailing list here: https://forms.gle/pX8v2U4CktAcz8s78 You can also sign petitions to pressure our government to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, like this one: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/support-the-nuclear-weapons-ban-treaty — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Christiansen, Gordon S. Survival in Nuclear War a Vanishing Probability. Connecticut College, 1961. — Further Resources “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed