|

Covid-19 has disrupted many of our Thanksgiving plans this year, but perhaps this disruption can give us an opportunity to reevaluate what the holiday really means. Thanksgiving is one of those holidays that is tied to a story that has become enshrined as an essential part of the history of the United States: the landing of the Mayflower, the assistance from Squanto, surviving the harsh winter, etc. How many children this year will be taught the story of hard-working Pilgrims and friendly Indians coming together for the first Thanksgiving? How many teachers will leave the story there? What kinds of harm, misinformation, and false understandings of the world do we perpetuate when we simply repeat the traditional Thanksgiving narrative? If we truly wish to respect Native Americans, we must listen to Indigenous voices.

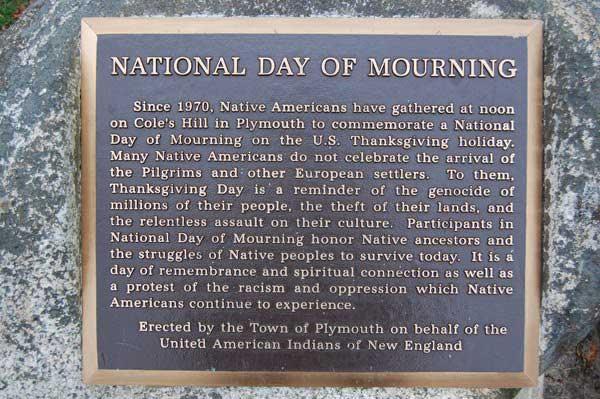

“THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG” To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970 ABOUT THE DOCUMENT: Three hundred fifty years after the Pilgrims began their invasion of the land of the Wampanoag, their "American" descendants planned an anniversary celebration. Still clinging to the white schoolbook myth of friendly relations between their forefathers and the Wampanoag, the anniversary planners thought it would be nice to have an Indian make an appreciative and complimentary speech at their state dinner. Frank James was asked to speak at the celebration. He accepted. The planners, however , asked to see his speech in advance of the occasion, and it turned out that Frank James' views — based on history rather than mythology — were not what the Pilgrims' descendants wanted to hear. Frank James refused to deliver a speech written by a public relations person. Frank James did not speak at the anniversary celebration. If he had spoken, this is what he would have said: I speak to you as a man -- a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction ("You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!"). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so. It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt's Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people. What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called "savages." Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other "witch." And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the "savage" and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again. The white man used the Indian's nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman -- but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we Indians have been termed "low man on the totem pole." Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons. What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as "civilized" people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags'] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty. History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood. The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his "savageness" has boomeranged and isn't a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian's temperament! High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians! Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently. Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting We're standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us. We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail. You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian. There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We're being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours. Wamsutta September 10, 1970 Source: James, Wamsutta (Frank B.). “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG.” United American Indians of New England. http://www.uaine.org/suppressed_speech.htm November is Native American Heritage Month, and Thanksgiving is just one week away. While Thanksgiving is a holiday fraught with a problematic history, it is also ostensibly a day to thank Native American contributions to the history of the United States. But of course, many of us are canceling Thanksgiving plans this year to keep our families safe as the covid-19 pandemic surges across the country. And with President Trump still refusing to concede the election and instead continuing to promote baseless conspiracy theories, some might think that it is a mistake to focus so much attention on the social representation of a small minority population at such a crucial time. A lack of accurate, positive representation leads to a reliance on easily manipulable and usually negative stereotypes, which in turn leads to the systematic dehumanization of the minority group. Combined with other societal narratives of “natural” entitlement and being threatened on all sides, this deadly mix has historically led to genocides. Indeed, both the means and the reasons used by the Nazis to perpetrate ethnic cleansing in Eastern Europe were inspired by the American conquest, cleansing, and forced resettlement of the American Indians of the Western United States.

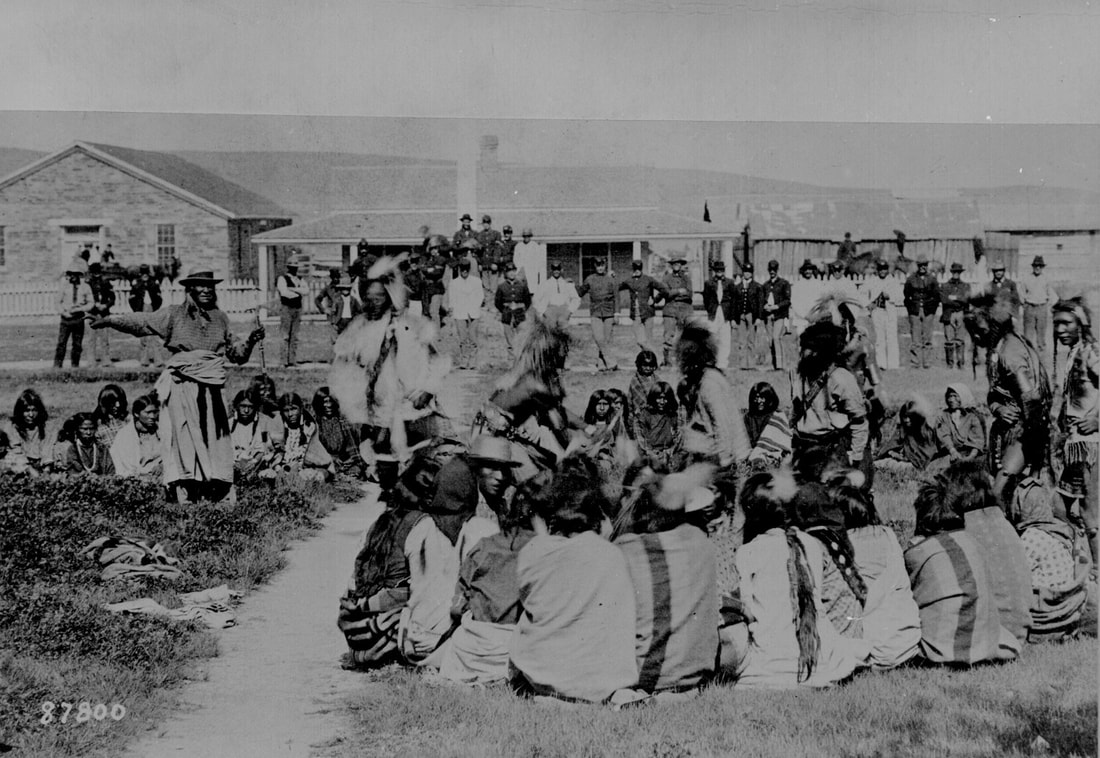

During the “Indian Wars” between 1846 and 1890, the U.S. massacred countless Native peoples and forced the rest onto “reservations” of unwanted tracts of land in order to open up desirable land for settlers. One way or another, Native peoples were expected by White Americans to be “eliminated” or else to “disappear” on their own. Not too long ago, these atrocities were celebrated as advancements in human progress, not just in the United States, but in Nazi Germany. According to Carroll P. Kakel, III, Hitler conceived of the German war in Eastern Europe as a colonizing war of ethnic cleansing to remove Slavic and Jewish peoples to make way for lebensraum, “living space” for Germans. Hitler himself encouraged his close associates to “look upon the natives [of Eastern Europe] as ‘Redskins’” of the American West. If the endgoal of both colonial wars was the removal of the Other to make space for White or German settlers, then the concentration camps of the Holocaust can be seen as an upgraded, more efficient Native reservation. Of course, the entire process of conquering and destroying Native peoples in the American West was just a small part of the massive racist project in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. James Q. Whitman has pointed out that Nazi Germany repeatedly found inspiration in restrictive American racial laws, not only with respect to Black Americans, but with all other non-“nordic” peoples. In fact, in the early 20th century, the United States led the world in racist law -- at least in the eyes of the Germans, Brazilians, Australians, and South Africans who implemented infamously racial codes in their own countries modeled after the American ones. As Whitman points out, Nazis themselves had a difficult time finding other models for racist codes like anti-miscegenation laws, except in the case of the “classic model” of the United States, where there was a robust tradition of forced segregation, restrictive racial immigration quotas, and second-class citizenship. Perhaps it is shocking to learn that the Nazis themselves were inspired by the American treatment of Indigenous, Black, and other non-White peoples. Most Americans do not associate the United States with fascism or Nazism -- we fought them, after all, didn’t we? Some have heard that prominent American figures like Henry Ford and Walt Disney were Nazi sympathizers before the attack on Pearl Harbor, but generally consider such information as curious details of eccentric tycoons during “a different time” in history. Some have even heard of the American Nazi rally in 1939 that attracted more than 20,000 people to Madison Square Garden. But most Americans would likely deny that any genocides have ever occurred in the United States -- not out of denialism, but out of historical misunderstanding and confusion about what genocides actually are. But then there are also those who believe in the “White genocide” myth, or the “Great Replacement” variation. The conspiracy theory is shockingly popular in some form or another among White conservatives and reveals the anxieties over ethnic diversity and the atrocities committed upon People of Color. Those who believe the “White genocide” myth fear that, given the chance, African-Americans would start a race war to exterminate White people out of revenge for slavery, disenfranchisement, terror, and more. The “Great Replacement” idea is more subtle, stating that unending waves of immigranion into Western countries like the United States will lead to the rapid growth and spread of non-White people, ultimately ending in the “replacement” and erasure of Whiteness and Western culture. Both of these variations often point to some shadowy group directing these massive demographic shifts specifically to exterminate White people. Strangely, these imaginary “globalist” or “New World Order” groups are usually composed of Jewish people. The United Nations defines “genocide” as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

Since there is no secret group imposing such policies on “White people” generally, and Black Americans time and again have faced violence with resolute nonviolent action. Those conspiracy theories are pure fantasy, but even entertaining them can be dangerous. If the preceived threat is as existential as death, replacement, and erasure, then the logic of those fantasies must always end with a kind of preemptive genocide or other atrocity to “protect” the “White race.” This is exactly the logic that led many ordinary Germans to look away from the worst atrocities their government committed upon Jewish, Slavic, and other peoples. It’s the logic that excuses separating children from their parents and locking them in cages today. It’s the logic that makes a threat out of any Black man, and what lets their murderers escape justice time and again.. The online series The Man in the High Castle, based on the novel by Philip K. Dick, takes place in an alternate 1960s in which the Axis powers won the Second World War. At one point in the series, a White asylum seeker studies with a Hitler Youth to become a naturalized citizen of The Greater Reich, which spans most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. As they study, the Hitler Youth brings up a question “about American exterminations before the Reich.” The asylum seeker asks with confusion, “exterminations?” to which the Hitler Youth replies almost with amusement: “Didn’t they ever teach you about the Indians?” Let’s just make sure we get the story straight. Sources and Further Reading: Cochran, David Carroll. “How Hitler found his blueprint for a German empire by looking to the American West.” Waging Nonviolence, 7 October 2020. https://wagingnonviolence.org/2020/10/hitler-found-blueprint-german-empire-in-the-american-west/ “Genocide.” United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide.shtml Kakel, Carroll P. The American West and the Nazi East: A Comparative and Interpretive Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Schwartzburg, Rosa. “No, There Isn’t a White Genocide.” Jacobin, 4 September 2019. https://jacobinmag.com/2019/09/white-genocide-great-replacement-theory Whitman, James Q. Hitler's American Model: the United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press, 2018. On Tuesday, November 11, many Americans celebrated Veterans Day, a tradition that has been held in the United States since 1954. The holiday began as “Armistice Day” to celebrate the end of the First World War; as many school children around the world are taught, on “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” of 1918, the conflicting nations of the Western Front finally laid down their arms. But after almost four decades and a few more wars, various veterans service organizations in the United States petitioned Congress to change the name of Armistice Day to “Veterans Day.” These organizations argued that the holiday should be opened up to honor all American veterans. After all, hadn’t those soldiers in the Second World War and the Korean War risked and sacrificed just as much as the doughboys of the First World War?

The argument seems reasonable until one stops to consider the original purpose for the holiday. Armistice Day was meant to celebrate an armistice -- an end to fighting before a more permanent peace treaty can be determined. And this particular armistice was particularly important. Although now treated primarily as the prelude to the Second World War, the psychological and societal trauma of the First World War cannot be overstated. The conflict was seen at the time as the ultimate existential war, and indeed the First World War collapsed four empires: the Russian, the Ottoman, the Austro-Hungarian, and the German. Deadly new technologies were deployed on the battlefield for the first time. Poison gas, machine guns, and other industrialized weapons helped kill a combined total of almost 10 million soldiers. Nations depopulated their own towns of able-bodied young men, sending them to their deaths en masse as cannon fodder. Finally, largely due to the transport of diverse peoples around the world to cramped and unsanitary conditions, and then sending those people back to their distant homes, the influenza pandemic crossed the globe at the end of the War and in its wake, killing 50 million more people by some estimates. Armistice Day emerged across the world to help collectively process the incomprehensible destruction and loss of life that resulted from the First World War, and to commemorate the moment when the leaders of all involved parties agreed to begin the process to end “the war to end all war.” The United States entered on the Allied side with fresh troops late in the war, and US President Woodrow Wilson emerged as the most influential arbiter of the eventual peace process. Starting before the US entry into the First World War, President Wilson urged the warring countries to seek “peace without victory.” Even after the US entry into the War, Wilson continued to develop his plan for a lasting international peace, which he eventually delivered to Congress on January 8, 1918 as the “Fourteen Points.” Wilson outlined several proposals that he believed would mitigate or neutralize altogether the factors that caused The Great War to begin in the first place: a prohibition on secret international treaties, freedom of navigation in the open sea, free trade, arms reductions, the restoration of recently conquered lands in Europe, etc. Notably, Wilson’s guidelines did not include a demand for reparations of the losing side, but rather implied shared responsibility of all parties for the War. The heart of his message, if not in the text itself, was that lasting peace could only be built through equitable relations between nationstates, the self-determination of nations, and the consent of the governed -- concepts central to the American mythology. Although the speech and its general message was largely met with approval in the United States and by most of the Triple Entente (with the exception of France’s Prime Minister Clemenceau), it was picked up and repeated most passionately by the peoples of the colonized world. On the streets of Beijing, citizens celebrated the end of The Great War carrying signs with Wilsonian slogans on them. The imam of Yemen sent a cable to Wilson asking for his support in the cause of Yemenian self-determination. African-American leaders led by the preeminent W.E.B. Du Bois joined their Afro-Caribbean and African counterparts in Paris for the Pan-African Congress to draft their own proposals for the post-war future of Africa. In 1919, as the Paris Peace Conference was getting underway, a 28-year old Ho Chi Minh, future freedom fighter and leader of the Communist Party in Vietnam, wrote to President Wilson requesting a private audience to hear his case for Vietnamese liberation from French colonial rule -- legend says that he even rented a suit for the occasion, but alas, the meeting never occurred. Unbeknownst to the future revolutionary, Wilson had been stricken with influenza weeks before. After the worst had passed, Wilson never fully recovered his vigor, and some historians point to his period of sickness as a major reason why he was ultimately unable to implement his Fourteen Points. Wilson’s failure at the Paris Peace Conference and the irony of Wilson’s own infamous personal racism notwithstanding, the ideas and values of the Fourteen Points shaped anticolonial thought for years until communism took its place. Colonized peoples were inspired and energized by Wilson’s words, looking to the United States as the leader of the free world, long before that phrase would be invented with a whole different set of connotations -- after all, the United States was the first to win its independence from the European colonial powers. And so it is especially ironic that the United States, the country whose leader fought the hardest for the right of self-determination, equality, and consensual governance of all peoples following the First World War, has been the country most responsible for interfering with democratic governments around the world since. Just a few years following the end of The Great War, US troops would join an international coalition to prevent Russia from implementing a popular communist government. In 1949, the democratically elected government in Syria was overthrown by a Syrian Army chief of staff with extensive ties to the CIA. In 1953, the CIA directed a coup in Iran to oust the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh to instead reinstate the constitutional monarch-turned-despot Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In the 1960s, the United States invaded Vietnam, just as the Vietnamese people liberated themselves from French rule. Guatemala, 1954. Indonesia, 1957-1959. Democratic Republic of Congo, 1960. Cuba, 1961. Brazil, 1964. Chile, 1964 and again in 1970-1973. Indonesia, 1965-1967. Bolivia, 1971. Afghanistan, 1979-1989. El Salvador, 1980-1992. Chad, 1981-1982. Nicaragua, 1981-1990. Grenada, 1983. Haiti, 1991. Venezuela, 2002 and again in 2019-present. Palestine, 2006-2007. And even those are just some examples of US military and political interventions; they say nothing about the outsized influence of the American dollar in international affairs, nor the exploitative international policies that have contributed to that influence. Garett Reppenhagen (US Army veteran and Executive Director for Veterans for Peace) summarized that connection succinctly in Waging Nonviolence: “The cultural identity [of militarism] is now so ingrained in our society that we unquestionably follow any military adventure despite the fact that poor people end up killing and dying and those who didn’t serve are handed the bill afterwards.” But the irony goes even beyond that. Armistice Day itself was never originally meant to be a holiday to honor soldiers who died in war; in the United States, Memorial Day fulfills that function. And yet, many other countries, notably those part of the Commonwealth of Nations, changed the name of the holiday to Remembrance Day during or shortly following the Second World War with the express purpose of honoring all patriotic soldiers who died in war. Armistice Day could be considered a day of mourning, but the mourning was never just about soldiers; the mourning included families, communities, nations. Despite the deadly serious, existential threats that the First World War presented to the powers of the time, it was also widely considered an incredibly wasteful and pointless war to have begun in the first place. According to historian Laurence Lafore, Europeans of the late 19th century believed that they were building a harmonious and prosperous future for human civilization: “Modern ideas were triumphing everywhere. Europe would soon be organized on a rational basis, its political and social symmetries would reflect the symmetry of nature and the universe. And it was going to happen, was happening, faster than anyone could have imagined ten years earlier. All that was needed now was hard work and common sense and education, and in the lifetimes of men already born the rising sun would light a Europe of perpetual peace and progress.” Considered within the context of those aspirations, the First World War becomes a cautionary and tragic tale, a catastrophe that Europe at its peak alone brought upon itself. The observance of Armistice Day could even be seen as a critique of war itself, a warning to those who think they can control the violence once it starts, and as a hopeful wish that future peoples would not make the same mistakes of the past. While observing Veterans Day, that hopeful wish is absent. Sources and Further Reading: Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Penguin Books, New York. 2005. Hagemann, Hannah. “The 1918 Flu Pandemic Was Brutal, Killing More Than 50 Million People Worldwide.” NPR. 2 April 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/02/826358104/the-1918-flu-pandemic-was-brutal-killing-as-many-as-100-million-people-worldwide “History of Veterans Day.” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 20 July 2015. https://www.va.gov/opa/vetsday/vetdayhistory.asp Lafore, Laurence. The Long Fuse: An Interpretation of the Origins of World War I. J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia. 1971. Manela, Erez. The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. Oxford University Press, New York. 2007. Osborne, Samuel. “Armistice Day, Remembrance Day and Veterans Day - what’s the difference?” The Independent. 11 November 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20181118032603/https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/armistice-day-remembrance-day-and-veterans-day-whats-the-difference-a6730081.html Reppenhagen, Garett. “Let’s reclaim Armistice Day.” Waging Nonviolence. 11 November 2020. https://wagingnonviolence.org/wr/2020/11/lets-reclaim-armistice-day/ Wilson, Woodrow. “Fourteen Points.” ourdocuments.gov. 1918 (accessed 11 November 2020). https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=62&page=transcript Twenty years ago, the United States Presidential election was undergoing a crisis. On Election Night, November 7, 2000, the nation waited with bated breath as Florida was first announced for Democrat Al Gore, then Republican George Bush, then backpedaled completely, claiming the results too close to call with confidence. That night, the count in Florida saw Bush winning by just 1784 votes, automatically prompting a machine-recount. Three days later, the automated recount results showed Bush leading again, but only by a scant 327 votes. The Gore campaign requested manual recounts in four counties, in part citing possible malfunctions with some of the voting machines and the “chads,” the bits of paper hole-punched out of ballots. Some ballots seemed to have “hanging chads” and other incompletions, leading to possible miscounts with the machines. All of these requests were legal according to Floridian law, and reasonable given the extremely close margin between the two candidates as well as the outstanding issues with the automated counting machines. The Gore campaign organized a legal team to argue his case in the Florida Supreme Court, and was granted the deadline of November 25 to complete the recount. Gore seemed to have won the legal case, and as the recount went ahead, the corrected results seemed to be counting in his favor.

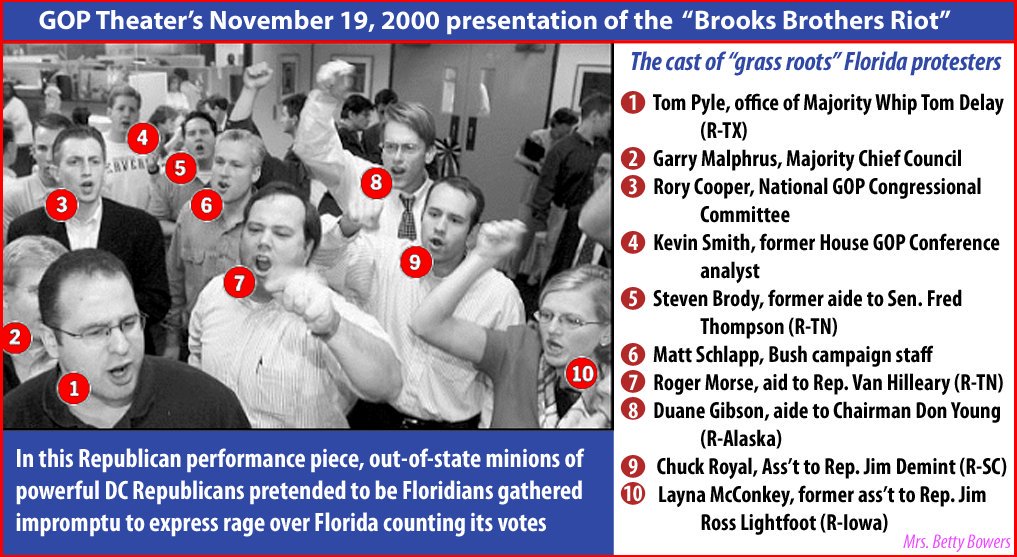

Meanwhile, however, a team of lawyers and other paid operatives of the Bush campaign and the Republican Party arrived in Florida. Well-coordinated and seasoned from working the campaign trail, they set about organizing protests among locals, trying to rile up conservatives and especially Cuban-Americans by conjuring up stories of leftists stealing elections. By November 22, with just three days left to count over 650,000 ballots, the officials at Miami-Dade County decided to focus on the 10,750 ballots that could not be read by the machines. By their own admission, Republicans expected the county to go to Gore. And so, as the counting continued, dozens of protesters led by those Republican operatives kicked, punched, and shoved themselves onto the floor of the building where the ballots were being counted, attempting to halt the process. According to the Democratic Chairman of Miami-Dade County at the time, Joe Geller, he was unable to even test his hypothesis about the machine errors due to protesters harassing him, accusing him of stealing ballots. While some Republicans maintain that most of the protesters were locals, there were enough Washington-types prominent in the crowd for the incident to be named for the distinctly conservative and expensive style of dress of most of the participants: “the Brooks Brothers Riot.” Among the Republican operatives involved were Roger Stone, former member of Nixon’s reelection committee, and current Texas Republican Senator Ted Cruz. These besuited thugs intimidated the Miami-Dade County Board with such a sudden and shocking show that the Board unanimously suspended the recount hours after the encounter. The Board was convinced that continuing the recount would be perceived as illegitimate by the public, and that that negative perception might damage the democratic process as a whole -- ignoring the fact that calling off the recount actually disenfranchised thousands of voters, and that stopping the count of all official votes is fundamentally anti-democratic. The recent reports coming out from Michigan, Arizona, and other battleground states of protesters attempting to disrupt or otherwise influence the electoral results through intimidation share some similarities with the Brooks Brothers Riot of 2000: mostly white, conservative, rowdy. Perhaps the most immediately noticeable difference is in the clothes: someone dubbed one of these ballot count disruptions in Michigan the “JC Penney Riot.” But focusing so much on the aesthetics of the protests ignores the most important difference between the Brooks Brothers Riot and these 2020 disruptions: the riot in 2000 was planned, organized, and executed by political operatives with months of experience on the presidential campaign trail. They knew each other, had worked together, trusted each other. With far less participants than in the large pro-Trump rallies being held now, those few Brooks Brothers rioters coordinated their demonstration so effectively that they got what they wanted within hours. These protests today, whether organized by locals on the ground or people within the Trump administration, so far do not seem to be nearly as well-organized. While President Trump has called for voter intimidation for weeks, it appears that he has not put in the work to actually organize such efforts. On the other side, however, national groups like Protect the Results, Election Defenders, and Choose Democracy have been preparing for weeks to ensure the elections are safe, accessible, and legitimate for all. Those groups have been analyzing the threats to the election, training people in de-escalation and nonviolent action, and coordinating with local groups for local efforts. The relative lack of voter intimidation, conflicts, and other issues this year despite calls to do so can likely be credited in-part to these groups. And if some of the present pro-Trump demonstrations continue to grow and even organize themselves, these same groups will still be here ready to respond. We must remember that politics is about power. Foreign observers have said that the institutions of American democracy are more fragile now than ever. Americans themselves openly worry about an imminent second civil war. But American conservatism has always held the rest of the country hostage against itself, using violence or the threat of violence to coerce society and government. Proud Boys and Oathkeepers are just some of the more recent incarnations of the long history of organized American racism and xenophobia. In 2019, Twitter made controversial news when it was revealed that executives at Twitter refused to implement an automatic content filter for White supremacy and neo-nazism because too many currently seated US Republicans would be kicked off the platform. A refrain circulating the internet goes: “Racism is so American that when you protest it, people think you are protesting America.” Perhaps we should not be so shocked that racist gangs and militias like the Proud Boys and the Oathkeepers have been praised repeatedly by the sitting President, and that members are often indistinguishable from “normal” community members. Maybe with the collective trauma of 9/11 -- and all the other disruptions that followed -- most Americans forgot about the Brooks Brothers Riot as just one more issue among the seemingly endless problems that plagued the 2000 election results in Florida. But it should have been a wake-up call. It’s long since time to examine our history honestly, without excusing or brushing aside the repeated pattern of right-wing violence as legitimate expressions of political power. Sources & Further Reading: Berman, Ari. “How the 2000 Election in Florida Led to a New Wave of Voter Disenfranchisement.” The Nation. 28 July 2015. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/how-the-2000-election-in-florida-led-to-a-new-wave-of-voter-disenfranchisement/ Cox, Joseph and Jason Koebler. “Why Won’t Twitter Treat White Supremacy Like ISIS? Because It Would Mean Banning Some Republican Politicians Too.” Vice. 25 April 2019. https://www.vice.com/en/article/a3xgq5/why-wont-twitter-treat-white-supremacy-like-isis-because-it-would-mean-banning-some-republican-politicians-too Gabbot, Adam. “Two decades after the 'Brooks Brothers riot', experts fear graver election threats.” The Guardian. 24 September 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/sep/24/us-elections-2020-violence-fears-brooks-brothers-riot Heye, Douglas. “I was in the 2000 ‘Brooks Brothers Riot.’ Trump supporters are way out of line.” The Washington Post. 5 November 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/11/05/trump-stop-count-maricopa-detroit-protests/ Kim, Richard. “Why The Brooks Brothers Riot Matters Now.” HuffPost. 5 November 2020. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/brooks-brothers-riot-trump_n_5fa44256c5b623bfac4d4043 Miller, Michael E. “‘It’s insanity!’: How the ‘Brooks Brothers Riot’ killed the 2000 recount in Miami.” The Washington Post. 15 November 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2018/11/15/its-insanity-how-brooks-brothers-riot-killed-recount-miami/ Shuham, Matt. “‘Brooks Brothers Riot’ Redux: GOP Sends Supporters To Swarm MI Vote-Counting Center.” Talking Points Memo. 4 November 2020. https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/brooks-brothers-riot-redux-gop-sends-supporters-to-swarm-mi-vote-counting-center Steinbaum, Marshall. “Brooks Brothers Riot.” Jacobin. 22 September 2016. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/09/trump-brexit-racism-xenophobia-globalization-gop/ Wolf, Cam. “The Brooks Brothers Riot, the J.C. Penney Skirmish, and the Changing Republican Uniform.” GQ. 5 November 2020. https://www.gq.com/story/brooks-brothers-riot-2020 |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed