|

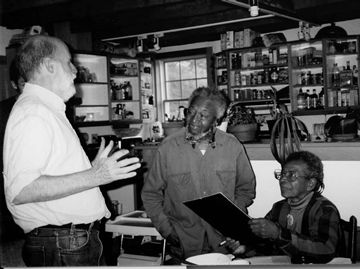

(Chuck Matthei (left) with Wally and Juanita Nelson. Photo: Peggy Scherer) This year, we mark the 20th anniversary of the death of Chuck Matthei, a key member of VPT’s history. Chuck first arrived at VPT the morning after the barn was burned in October 1966. At the time, VPT was known as the CNVA Farm, and Chuck had previously met several people involved in the wider CNVA community through Peacemakers and the Catholic Worker. During his days of itinerant activism, Chuck made the Peace Trust another one of his homes. Influenced by Gandhi and interested in nonviolent economics, Chuck became involved with Bob Swann's work on community land trusts after arriving at VPT. Bob invited Chuck to join the board of the Institute for Community Economics (ICE), which was based in Voluntown and then Boston.. Chuck became the Executive Director of ICE and moved the organization to Greenfield, MA. Chuck ultimately left ICE to develop his Equity Trust program into an organization which moved back to the Peace Trust in 1991. He had the old sauna renovated, but he hadn’t lived in it for long before he became ill with cancer. He died at Ahimsa where he was taken care of, and visited by, many friends. Directly below is Chuck Matthei’s obituary written by Joanne Sheehan for the War Resisters League magazine Nonviolent Activist in 2002. Below that is Robert Ellsberg’s reflections on Chuck’s life, work, and philosophy. -- Born on Valentine’s Day in 1948 in Wilmette, IL, Chuck opposed the growing war in Vietnam and decided to resist the draft by the time he was 18. He often told the story of staying with Wally and Juanita Nelson on his way to a Peacemakers Orientation Program. Wally told Chuck “Our house is your house, for as long as you need it. You’re always welcome here.” Wally, who died five months before Chuck (see NVA, July-August 2002) remained one of his closest friends. Throughout his life, he offered hospitality and encouraged others to do the same. Chuck remained close to movement “elders” like Ernest and Marion Bromley, Maurice McCrackin, Dorothy Day and Marj Swan, all of whom he met at the Peacemakers gathering. He spent time at the Peacemakers community in Cincinnati, the Catholic Worker Farm in Tivoli, NY, and the Community for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) in Voluntown. Chuck also befriended Lolita Lebrun, the Puerto Rican independence activist, visiting her at the women’s prison in Alderson, WV. Inspired by World War II total resister Corbet Bishop, Chuck became a total resister, refusing to work, walk, eat or drink when arrested. Arrested for draft resistance in February 1969, Chuck noncooperated as he was brought back to Chicago for trial. After discussions with him, the judge, who usually sentenced draft resisters to five years in prison, dropped the charges the next month. Chuck’s charisma often had a transformative effect on those who met him. Chuck and I were in the same New Hampshire armory after being arrested for occupying the Seabrook nuclear power plant in 1977. He went 11 days without food or water. I watched as Chuck interacted with a National Guard doctor who initially came to convince Chuck to eat, but developed a deep respect for him. Chuck spent a lot of time on the road, connecting with people and connecting people, participating in actions and inspiring people to act. In telling the story of the western Massachusetts Traprock Peace Center, Randy Kehler credits Chuck “the ever-present cross pollinator of the movement” for bringing together the people who then developed the Nuclear Weapons Freeze campaign. Chuck lived at New England CNVA while Bob Swann developed his community land trust philosophy. Chuck’s approach to poverty and inequality linked activism, economics and property issues into a powerful political message. From 1980 to 1990 Chuck served as Executive Director of the Institute for Community Economics (ICE), then based in Greenfield, MA, and now located in Springfield, MA. ICE pioneered modern community land trust and loan fund models. As Founder and Director of Equity Trust, Inc. (founded in 1991 and based in Voluntown at the site of the old CNVA farm), he focused on alternative models of land tenure and economic development. Equity Trust has provided technical and financial assistance to projects all across the United States and in Central America and Kenya. Two-and-a-half years ago, after learning that Chuck had terminal cancer, I encouraged him to write an article that would explain his understanding of nonviolent economics. Together we wrote “Toward a Nonviolent Economics,” for WRL’s Guns Greed Globalization. (An edited version appears in NVA, May/June 2001.) Chuck touched many people deeply with his conscience, discipline and commitment. His work on economic alternatives has made a difference in many lives. Even though Chuck didn’t live long enough to become an elder, he lived an incredibly full life. —Joanne Sheehan Joanne Sheehan, organizer for WRL/New England, first met Chuck in the WRL building in the early 1970s. More on Chuck and his work can be found on www.equitytrust.org. -- (Click on the image below to download the PDF, or see the whole issue at The Catholic Worker) —

Support Us If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Ellsberg, Robert. “Chuck Matthei, 1948-2002.” The Catholic Worker. 1 January 2003. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=CW20030101-01.2.11&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------- Sheehan, Joanne. “Chuck Matthei, 1948-2002.” Nonviolent Activist. November-December 2002. Second article in the link: https://www.warresisters.org/nva/chuck-matthei-1948-2002 Almost exactly sixty years ago, in September 1962, the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) officially changed its headquarters address to a historic farm in Voluntown, Connecticut. At that point, many of the members had been living in Connecticut for just over two years — ever since the first Polaris Action Summer in 1960, which had kicked off a radical new antiwar movement in the region. More were locals who were inspired to join the movement. With the acquisition of the farm in Voluntown, the New England CNVA could feel a little more secure as well as have the space and resources to develop a degree of self-sufficiency. Long before the hippie movement, the rise of the New Left, the environmental movement, or many other progressive groups, the CNVA had recognized the necessity for American society to change to one that works in harmony with the natural ecology, promotes a fair and egalitarian economy, defends human and civil rights, and opposes war. Indeed, the CNVA was one of the first groups in the United States to articulate the connections between all of these seemingly separate issues. The following pamphlet gives a good overview of the goals, methods, purpose, and general history of the New England CNVA over its first decade. For such a relatively small group, the range of projects pursued and relationships made is staggering. From the Providence CORE chapter and the Hartford Black Caucus all the way to Guatamalan nuns, Japanese Buddhist monks, and beyond, the organization was not just a node in a network that spanned the globe, but was an active bridge-builder in that network. Yet the New England CNVA never lost sight of the important work to be done locally on the ground. The move to the farm signaled the New England CNVA’s intention to establish a permanent oppositional presence in the vicinity of the “submarine capitol of the world” from which the organization could continue to press on Electric Boat workers’ consciences and promote the idea of economic conversion. We are proud to continue the New England CNVA legacy in Voluntown six decades later. (Click on the cover image below to download the full 8-page PDF) —

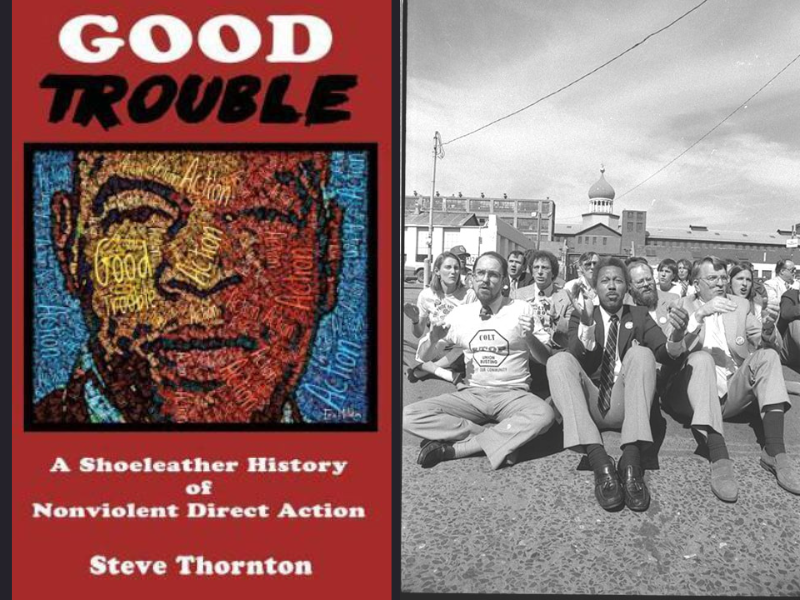

Support Us If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source Swann, Marjorie. Decade of Nonviolence: Through The Years With New England CNVA (c. 1970) On September 10, 1992, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which called for an outright ban on nuclear weapons testing involving critical mass (a requirement for the nuclear chain reaction which causes the detonation). Although adopted by the General Assembly, the treaty never came into force due to the refusal of eight key governments. While the United States was one of the eight that refused to ratify the treaty, the US government has since honored the terms of the agreement — however, the United States has continued to perform subcritical tests with regularity, and nothing legally prevents the United States from resuming critical mass tests at any time: a fact of which the rest of the world is all too aware. Over the past several months, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and NATO’s response has pushed the topic of nuclear weapons back into international affairs. We and others have illustrated the past and potential future horrors of nuclear war, but the dangers of nuclear weapons goes far beyond their intended uses in combat. History has shown that even just the testing of such weapons within one’s own borders has been rife with racist tragedies. In 2009, Dr. Bonnie Eberhardt Bobb wrote a piece about the infamous Nevada Test Site where the United States government has tested nuclear weapons starting in 1951, and where the very first demonstration of the Comittee for Nonviolent Action occurred in 1957. Dr. Bobb had visited the site repeatedly through the 1980s and 1990s, focusing specifically on the experiences of Native peoples in the area with regards to the weapons testing and subsequent radioactive fallout. She found that Native peoples disproportionately suffered from radiation due to every manner of neglect on the part of the United States government. We present her report in WIN Magazine below. As an alternative path to nuclear disarmament from the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban, the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force on January 22, 2021. The new treaty outright bans the possession or use of nuclear weapons by participating parties. It was meant as a “path forward” without the support of the officially recognized nuclear powers, including the United States. As of the time of writing, 66 governments around the world have ratified the treaty (about a third of all of the world governments), and twenty more have signed but not yet ratified. For the sake of past and potential future victims of nuclear weapons, whether during active war or “peacetime” testing, we must continue to work to erase these cursed items from the world. (See below for the article from WIN Magazine) -- Invisible Legacy: Western Shoshone & the Nuclear Era Dr. Bonnie Eberhardt Bobb In the 1980s, I traveled to Nevada several times to protest nuclear weapons testing at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) about 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas. A friend of mine was a “nuclear veteran,” one of the 6,000 soldiers positioned within a mile of one of the above-ground explosions in the 1950s to test the effects of the bomb. In other words, he was a subject of government experimentation without his knowledge or consent. As I stood at the cattle guard, facing a line of armed guards and sheriff’s deputies blocking the road to the mysterious desert facility, I wondered how much radiation I was breathing in with the heat and blowing sand. But I was young enough then that I did not worry about the possible long-term health effects, even though I knew the half-life of plutonium to be over 26,000 years. On my second trip to NTS, I met a Western Shoshone man, William Rosse, who was speaking at the event. He explained that the NTS was on land stolen from the Western Shoshone, who had signed a treaty of peace and friendship with the United States in 1863. The treaty, which was ruled in full force and effect in federal court, described the Western Shoshone boundaries: most of what we know as the state of Nevada, a bit of Utah, Idaho, and down to the Mojave Desert in California. It was huge—and it surrounded the test site. I realized that helping the Shoshone and recognizing the treaty were the keys to stopping the nuclear testing. In 1996, I moved to Nevada to work full time on assertion of Western Shoshone rights and stopping nuclear proliferation. If radiation remains present for so long, where was it? It had to still be there. Above-ground testing began January 27, 1951, and continued through October 31, 1958, when a moratorium went into effect. When the Soviet Union resumed testing in 1961, so did the United States. The last atmospheric test at the NTS was July 17, 1962. But underground testing continued. In 1996, the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed, “prohibiting any nuclear weapon test explosion.” A total of 928 nuclear tests have taken place at the Nevada Test Site. Of these tests, 100 were atmospheric tests. These figures do not include sub-critical tests, which continue. Western Shoshone and Paiute groups in the area had more exposure to radiation because of their culture and way of life. A study by a Native group, Nuclear Risk Management for Native Communities, showed that radiation was not monitored in areas where Native people spent most of their time. Air monitors were in towns near highways, not near their isolated homes and hunting, fishing, and gathering areas, many of which were at higher altitudes with more potential radiation. Researchers had not considered that Native people were outside most of the time, ate wild game and plants, and used plants and animal hides in creating tools, drums, clothing, housing, and art. CONTAMINATION Despite the large number of nuclear tests with accompanying fallout and the fact that Western Shoshone have not given up their foraging lifestyle, there have been few studies of off-site soil contamination and no studies of residual fallout on Western Shoshone land or on the vegetation there. No studies could be found that studied the effects of radionuclides on traditional foods like pine nuts or berries. There have been no studies of health effects, nor any baseline studies of overall health in the area—either of Western Shoshone or any other population. During the nuclear era, the only scientific health and safety information about nuclear testing came directly from the Department of Energy (DOE), and most of the documents remain classified. Thirty-nine nonprofit and environmental groups sued the DOE to gain access to independent analysis and review of DOE site activities. The lawsuit resulted in a 1998 settlement with $6.25 million being set aside for independent review and analyses of activities at DOE sites. I assisted two Western Shoshone groups in getting funding to study radiation remaining in the soils of Nevada. Locating radiation in soil over such a large area is a daunting task. Radiation did not fall in a uniform pattern. It fell indiscriminately and then blew over the surface of the sandy soil. Because soil tests were so expensive, over $600 each, the number of sites we could test were limited. A plan was devised to increase the likelihood of finding nuclear testing-related radiation if it was present. First, 13 Western Shoshone ranging in age from 55 to 92 who lived in or used areas near the test site during the period of atmospheric testing were interviewed about their memories of the nuclear testing era, including specific locations of hunting, fishing, gathering, camping, and tribal ceremonies. Next, those areas were examined by Western Shoshone participants using hand-held radiation meters. Soil samples were collected in undisturbed areas with the highest levels of radiation. The collections were sent to the laboratory in Washington State that conducts testing for the Hanford Nuclear facility. Radionuclides chosen for analysis were products of nuclear weapons testing that had a relatively long half-life. Many fission products are short-lived and thus would not be detected. In addition to gross alpha, beta, and gamma spectrometry, individual tests for plutonium-239 (half-life 24,065 years) and -240 (half-life 6,537 years), the most carcinogenic substance on earth; tritium; strontium90 (half-life 29.1 years), which behaves like calcium and is taken into the bones, marrow, and teeth; cesium-137 (half-life 30.17 years); and americium-241(half-life 432.7 years), a man-made isotope produced during detonations, were analyzed. The interviews clearly showed that the Shoshone communities were never notified of testing, nor were they told that the radioactivity might be dangerous or how to protect themselves. People found out through radio or newspaper reports following a test. “They made it sound safe so we wouldn’t panic, but later on, everyone knew it was dangerous,” said an interviewee who asked to remain anonymous. MUSHROOM CLOUD Descriptions of the tests were vivid. In warm weather, most Shoshone slept outdoors under the trees and thus witnessed the tests. They described rumbling sounds, dust in the air, and brilliantly colored flashes lighting up the sky. Many in the south saw the “funny-looking” mushroom cloud. Food sharing was common. Rabbits, deer, and big horn were hunted and shared with the whole community. In the 1960s, word started to leak out that testing was dangerous. “We ate rabbits—head, neck, and limbs, too,” said an interviewee. “Then we saw lots of disease in the rabbits.” Animals started to appear with boils. “We didn’t know it was going to be bad and hurt people. We didn’t think about it. They said they were testing [and] ‘It’s not going to hurt you.’” An elder in his 90s remembered killing diseased deer with foul-smelling black balls the size of a dime inside the muscles. “Nothing grows now,” he observed. “More people died off, and the animals disappeared with them. Lizards, squirrels, rabbits, doves—they never come back. My dad told me that when all the Indians (Shoshone) die, the food will go right with them. They won’t have nothing. Everything will die off.” At the NTS, an elder took pitch off the pine trees and made a big ball to take home. One of the ethnographers said she shouldn’t take it, that it was going to make her sick. Another person was at an NTS ethnographic project and picked some pine nuts and put them in his pocket. The leader told him to throw them away and not eat them because of the radiation. They had never been told that. One elder recalled, “People sometimes lived to 115, but now they’re dying earlier and they’re obese from not being active. I blame that on the government. They closed off our dreams and goals of what we could achieve. They came in and told us we can’t own land and kicked us off from ranching. Then they gave us commodities and boarding school. Now they might destroy our pine nuts too. They killed all the plants, and nothing grows now.” Several Shoshone discussed a woman who had lived in Death Valley and moved to Beatty, Nev., when she became ill. When she died, they tried to move her and the skin fell off her bones. Another elder recalled how miners came into the area to explore the area outside Tonopah for uranium. Because of the Cold War, uranium production and self-sufficiency were encouraged. Many mining claims were filed because of high Geiger counter readings. Despite repeated digging, the miners found no uranium. The high readings were apparently from a radionuclide that had covered the fields. And, in fact, the soil studies showed the fields outside Tonopah, Nev., contained both plutonium and americium. The results from the soil sampling showed alpha and beta radiation above acceptable limits in all 52 samples, including areas not being monitored west of Tonopah. Cesium and strontium were present in some of the north and west samples. The concept of “downwinder” assumes plume direction. Most DOE studies are based on plumes traveling north and east. But is this correct? Wind patterns cannot be predicted. While most wind moves west to east, currents at 10,000 feet may move differently than those at 20,000 or 30,000 feet. The Western Shoshone studies indicate that radiation has moved west and south. In fact, doses from the west were higher than doses in the assumed fallout areas. Is the radiation from another source, like Chernobyl? Perhaps there are more “downwinders” than we think. The complete studies, funded by the Monitoring and Technical Assessment (MTA) Fund, can be found at www.clarku.edu/mtafund/prodlib/tuppipuh/tuppipuh.pdf and www.clarku.edu/mtafund/prodlib/yomba/yomba.pdf, or contact Dr. Bobb at [email protected]. See the original article at the War Resisters League website: www.warresisters.org/win/win-spring-2009/invisible-legacy-western-shoshone-nuclear-era -- Further Resources Berrigan, Frida. “On Friday, ‘Say no to nuclear weapons.’” The Day. 1 August 2021 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.theday.com/article/20210801/OP03/210809975 “Electric Boat History.” General Dynamics: Electric Boat. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. http://www.gdeb.com/about/history/ “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. August 2020 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat “Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/tpnw/ Wellerstein, Alex. “Nukemap.” Nuclear Secrecy. [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/ “What if We Nuke a City?” Kurzgesagt — In a Nutshell. 13 October 2019 [Accessed 4 August 2021]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iPH-br_eJQ Two years ago, we posted the following excerpt from Steve Thornton’s book GOOD TROUBLE: A Shoeleather History of Nonviolent Direct Action. The story tells of the workers of the Colt Firearms factory going on strike starting in January 1986 — almost exactly a hundred years after the Haymarket massacre which inspired the original international Labor Day. Perhaps surprising some, many local nonviolence resistance activists also joined to support the strikers and their families. Indeed, a critical part of the campaign’s success was its wide and diverse network of allied organizations and individuals: local politicians, religious communities, teachers and schools, etc. Notably, despite the violent products that the workers were expected to make, as well as the overwhelming police and private security forces opposing them, the labor campaign was conducted nonviolently, and was ultimately won without a single shot fired.

(See below for the excerpt from GOOD TROUBLE) -- The Colt 45: Peace Work with a Union Label May 13, 1986 The Colt Firearms factory has been producing guns since the 1800s, from pistols to Gatling guns and now, M-16 automatic weapons. The Colt name is known worldwide. Workers at Colt have tried to establish a union since the turn of the 20th century, and finally succeed in the 1940s. Now, in 1986, they are in a life or death struggle with a company that will do anything to break their union, United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 376. Colt intends to rollback the gains made over the years by the white, black, and Puerto Rican workforce. “We are not claiming that we are losing money, nor were we basing our proposals on the Company's financial condition,” admits the company’s top negotiator. Colt workers have already been protesting on the inside for more than a year against poor treatment and blatant attempts to bust their union. Led by shop chairman Lester Harding, activists have been disciplined, suspended and fired for nonexistent infractions. In response, they print the names of the fired workers on their shirts, and parade in the plant during break time to communicate their anger. Once the strike begins on January 24 1986, the 1,000 strikers attempt to stop scabs from entering the factory and taking their jobs. Frequent scuffles on the picket line are met with overwhelming force by the city police. There are many arrests during the strike’s first months. At one point UAW leader Phil Wheeler is slapped with inciting a riot, a serious felony charge. The boss at Colt knows that public opinion is important in this fight. He thinks he can sway that opinion with full-page newspaper ads. He harps on the picket line conflicts, laying the blame solely on the strikers. He explains how reasonable his negotiating demands are, and how unreasonable the UAW is. Thanks to the newly formed Labor /Community Alliance, the propaganda falls flat. On May 13 1986, forty-five community activists, elected officials, clergy members, teachers and others converge at the Colt factory on Huyshope Avenue, Hartford. They sit down, blocking the parking lot entrance and the scabs attempting to enter the factory. The group is dubbed the “Colt 45,” an ironic take on the company’s most famous product. The civil disobedience is no picnic. The Hartford Police captain in charge of the cops on the line has been accused of acting against the strikers from the beginning. The workers are proven correct when he quits the police force during the strike and takes a job as the new head of security for Colt. The nonviolent Colt 45 action is only one of many community support events and marches organized during the record four-year struggle. Critical to the strikers’ morale is the solidarity they get from other unions and the city and state lawmakers, who support a successful nationwide boycott of Colt products. In fact, the strike itself is the longest sustained nonviolent action in Connecticut history. Included in the Colt 45 are a number of peace activists. Is this some mistake? No, they say. They issue a public statement signed by many of the most locally prominent anti-war figures, who explain that union jobs are good for families and neighborhoods. They understand that workers have no power to choose what they make in this society. The activists want to build relationships with unions and rank-and-file workers to find common ground and ultimately achieve “economic conversion,” the process by which industry changes to peacetime production. There are only two sides in this fight, and they choose the workers. In 1990, UAW 376 wins big. The company finally gives in after labor court decisions have found that Colt has been a massive law breaker. Workers win $10 million in back pay and benefits. All strikers can return to their jobs. A coalition of the state government, private investors-- and the UAW-- have bought the company. Thirty years later, union veterans, community activists, and college students hold a “commemoration of courage” to celebrate the Colt strikers’ victory. At first, some openly question the event’s purpose: do they really want to remember those hard times? But still, many strikers and their spouses attend. When asked about good memories from their historic strike, they answer “the Colt 45.” (Good Trouble: A Shoeleather History of Nonviolent Direct Action is a riveting chronicle of stories that prove time and again the actions of thoughtful, committed people can change their lives and their country. It is a brisk, inspiring primer for veteran political activists and newcomers alike. Civil Rights struggles. “Fight for $15” strikes. Tenant occupations. LGBT campaigns. Each of the 40-plus examples in good Trouble focuses on the power of organizing and mobilizing, relevant in any context, and serves as an “emergency tool kit” for nonviolent action. Excerpt republished with permission from the author.) — Take Action The CT Committee for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons organizes pro-disarmament demonstrations throughout the year. To participate in these demonstrations against nuclear arms and in support of the UN’s Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, please get in touch with us on Facebook at facebook.com/voluntownpeacetrust or email us at [email protected]. — Support Us If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source Kohn, Sally. “Why Labor Day was a political move” CNN. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/09/01/opinion/kohn-labor-day/ midtowng. “Knights of Labor” Progressive Historians. https://web.archive.org/web/20070930082656/http://progressivehistorians.com/showDiary.do?diaryId=2041 Thornton, Steve. GOOD TROUBLE: A Shoeleather History of Nonviolent Direct Action. Hardball Press, 2019. https://goodtroublebook.com/ |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed