|

On the gray and rainy morning of December 1, 1960, one hundred and fifty people gathered at San Francisco’s Union Square in excited anticipation: a diverse crowd of students, minor celebrities, the religiously-motivated, and others, along with a couple filmmakers and half a dozen people in news and media. The air was chilly, the wind blustery, and perhaps some in attendance were considering going home when, “As if by Providence, the grey ceiling opened and a stream of sunlight washed the Square as the marchers entered.” After a warm reception and a couple send-off speeches from community leaders, the walkers lifted their signs and strode out. No one, least of all the walkers themselves, knew if they would be admitted into Eastern Europe when they finally arrived, or if they would even find hospitality everywhere in their own country -- volunteers were out establishing contacts to support the Walk in California even as the walkers left Union Square. Thus, as flashbulbs burst from cameras and supporters chatted and laughed as they strode beside, and the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace began its 6000 mile journey.

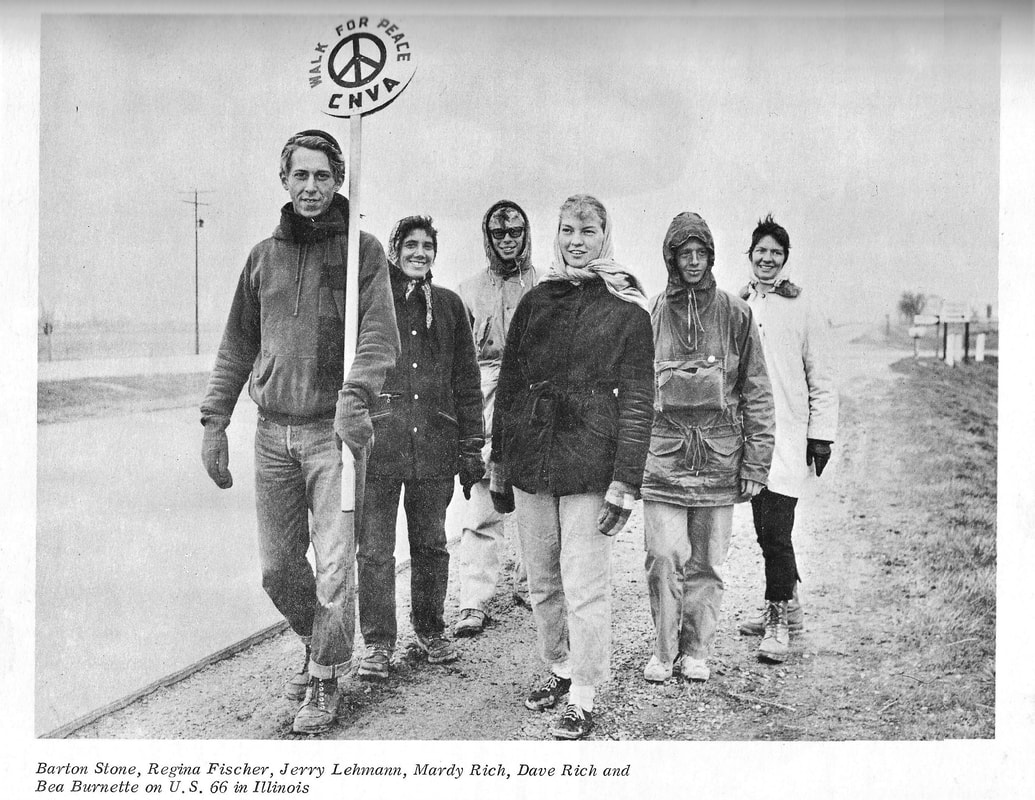

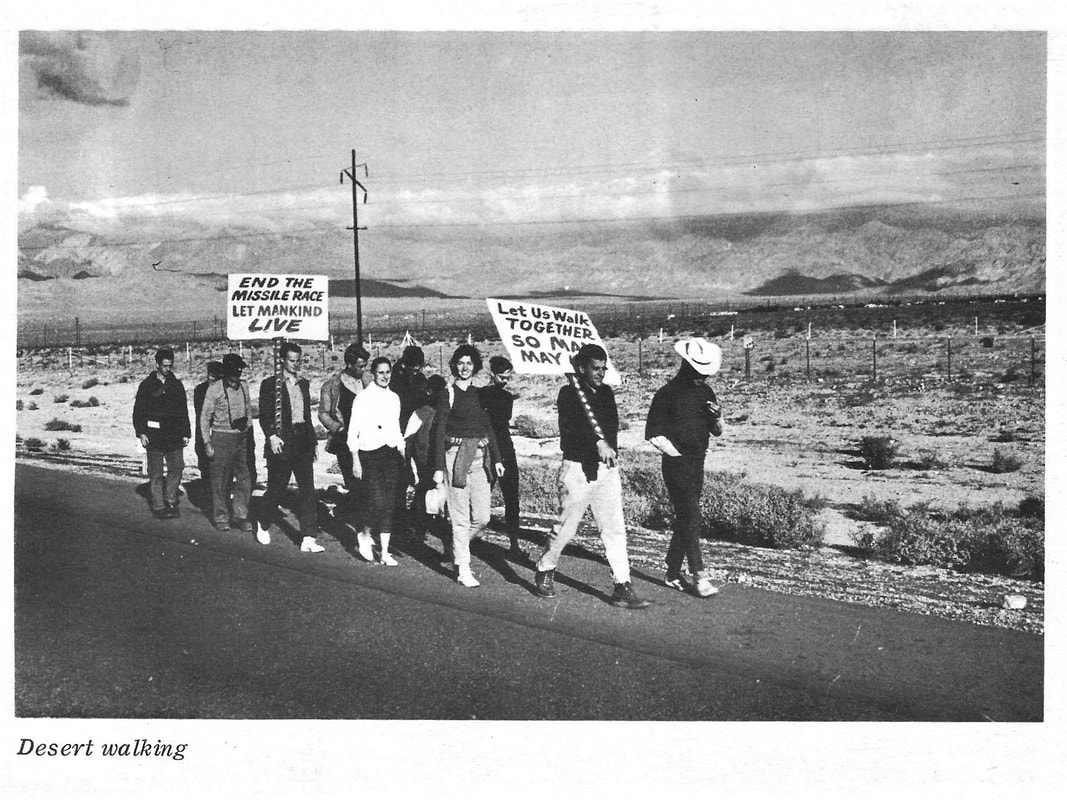

The whole project took a considerable amount of work to organize behind the scenes. So much had to be coordinated: meals, meetings and interviews with the media, rendezvous with local supporters, and especially overnight housing. Bradford Lyttle, one of the principal organizers of the Walk, started the Walk with the others, but eventually found himself zipping on ahead in cars and planes to coordinate. Lyttle especially organized a good amount of media coverage: a 10 minute radio interview here, a two hour radio interview there. Filmmakers even set up an interview between Brad Lyttle and Rand Corporation representative Herman Kahn, who had recently published the book On Thermonuclear War. It took the Walkers the entire first month to cross California and enter Arizona three days behind schedule -- a whole month of learning from painful mistakes and experience. They tested all types of boots and sneakers for walking -- Brad Lyttle estimated that the Walk wore out 200 pairs of shoes. They learned how to treat their blisters, and incorporated foot care into their routine. They learned the physical limits of their bodies, and that almost all of them would have to take the occasional break, at least until their bodies became used to walking an average of 23 miles every day. They learned that sending a car out a few miles ahead of the walkers to talk to the locals sometimes made the difference between free hot meals and empty stomachs. They learned the difference between coordinating in a small town versus a sprawling city: in Los Angeles, organizers had arranged for eight families scattered across the city to host the eight Team members, only to realize the difficulty of coordinating the transportation to each destination in a city like L.A. (especially before mobile phones). Perhaps most importantly, the Walkers learned how to work with each other. This “group of artists, intellectuals, mystics, anarchists and whatnot,” as Lyttle described them, learned to work through differences in opinions and make collective decisions -- despite the “desire for autonomous individuality [which] collides with our need for organization, resulting in relatively complete chaos most of the time.” Brad Lyttle was likely exaggerating about the chaos -- or perhaps he was accurate and it was exactly that creative individuality that also accounted for some of the Walk’s success. The Walk certainly attracted unique people. Bea Burnett was one early convert to the Walk. A corporate spokesperson who had been inspired by marchers at a meeting in San Francisco, Burnett threw herself into the project. At first, she volunteered for the advance work of securing food and housing for the walkers -- in the first week of the Walk, she even convinced local businessmen at a shopping center to give the walkers free lunches and haircuts. Barton Stone, a Buddhist who attended a meeting during the send-off for the Walk in San Francisco, was another early joiner. Others, like John Beecher, an eminent poet and English professor at Arizona State University, and his wife Barbara Beecher, an artist, had been developing their own pacifist feelings for some time, and took the Walk as their opportunity to finally commit to those feelings and do something. At a vigil at the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, ten men and women dressed in white and blue and calling themselves “Children of Light” joined the walkers. On Christmas 1960, Joan Baez showed up and played a short concert for the walkers -- she had visited Polaris Action in New London with Pete Seeger just a few months earlier. Most of January was spent in Arizona, where local receptions were less welcoming. In California, the Walk could usually get a platform, if not a sympathetic audience, at the universities; the worst the walkers would get was mild condescension at what the audience perceived as pacifist naivete. In Arizona, such privileges could not be guaranteed; en route to a speaking engagement organized by sympathetic faculty members of Arizona State University at Tempe, a crowd of over 50 hostile students threatened the walkers with violence if they attempted to proceed toward campus. Even after the marchers convinced the students to let them pass, the audience that ultimately attended the talk heckled and booed the walkers while holding signs like “EXTERMINATE THE ENEMY.” Members of the Team noted the influence of Barry Goldwater, The Arizona Republic, and the John Birch Society, creating a toxic atmosphere of isolationist conservatism and violent paranoia. Even the churches, reliable for a meal or place to spend the night in much of California, largely denied the Walk any help in Arizona. Time and again, advance workers would request assistance from individual church leaders as well as larger religious associations. Quakers and Unitarians were often most likely to answer the call, but it was no less disappointing when other denominations refused them. Some individual ministers who had initially welcomed the walkers even had to reverse their offers out of pressure from their hostile congregations. On the nights they couldn’t find shelter, the walkers camped. Arizona was where the walkers first experienced media blackouts regarding the Walk. In Tucson, a reporter told Team member Scott Herrick that the owner of the main Tucson daily had ordered that the Walk be ignored. Some of this institutional hostility could be explained by individual prejudices of locally powerful men, but the walkers began to suspect that a more coordinated effort might be organizing against them. Reports began to filter in about the FBI spreading rumors and false characterizations about the walkers to local military leaders and law enforcement, sending directives condemning the Walk and suggesting a “hands-off” policy to the media, and warning local chambers of commerce and ministers’ associations not to lend aid. Sometimes, these FBI directives were quite successful. Despite some moments of generosity and humanity along the way, the unfriendly pattern established in Arizona held throughout much of the American Southwest. But some communities perhaps never received the FBI message. When the Walk arrived in Alva, Oklahoma late on the evening of February 21, 1961, the walkers were not expecting what happened that night. From Brad Lyttle’s words about that night: “We had camped at a railroad overpass about a mile north of Alva. Immediately, people began coming to talk to us. There were several ministers who were interested but did not feel we were ‘safe’ enough to take in. Many students came. By the time we finished supper, cars were parked lining both sides of the highway and caused the police a bit of a traffic problem. What a scene. More cars continued to arrive. Our fleet of odd-looking vehicles parked around the green and orange tent, by camp-fire; guitars and singing, foodboxes, lanterns and paraphernalia strewn around. A crowd of fraternity boys parked up on the hill, gathered in a band, with torches. One boy had a bugle, another carried an improvised sign saying WORKERS ARISE. STAMP OUT THIRST. DRINK BEER. They walked yelling and jeering down to the camp, and became part of the crowd. At one time there were about 100 people, mostly students, from Northwestern State Teachers College gathered around our fire, but we must have talked to many more than that, for the crowd kept changing as some left and others came. These students were as a whole much different from others we had spoken to. They were more curious, open-minded, tried harder to understand what we were saying, less antagonistic. I got the impression too they were less informed about world affairs, not as ‘sophisticated’ as, for instance, the students in California. Many of them understood and agreed with us up to the point of taking personal action. They regarded Allan Hoffman and Betty Blanck [two Team walkers] as particularly curious specimens because of their frank atheism. Often they got sidetracked into theological discussions. “There were Five or six groups gathered around nuclei of two or three walkers. People drifted from one group to another. These students asked very intelligent questions which were obviously aimed at understanding, rather than discrediting what we said. “By 12:30 AM most of the crowd had left and many of us fell asleep exhausted. Dr. Beecher said that the last ones didn’t leave until 2:30 AM. He said it was one of the greatest experiences of his life.” Sources: Lyttle, Bradford. You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. Greenleaf Books, Raymond, New Hampshire: 1966. Peace of History

Around this time in September sixty years ago, three peace activists met at the Hygienic Restaurant (now Hygienic Gallery) in New London, Connecticut to plan the next steps in the campaign for nuclear disarmament. What they decided on was ambitious, unprecedented, and potentially dangerous: they were going to spread their message of peace across the United States, Western Europe, and the Soviet Union -- on foot. Over coffee and eggs in that historic restaurant on Bank Street, the idea for the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace was born. Since June 1, 1960, the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) had been in New London and Groton, CT for Polaris Action, a summer-long campaign to disrupt the production of nuclear-armed submarines at General Dynamics: Electric Boat and to educate the public about the dangers of the nuclear arms race. Most participants traveled in from other places and, according to the Hilary Harris documentary Polaris Action (1960), included “men and women, old persons and the very young, ministers and atheists, Negro and White, ex-servicemen and conscientious objectors.” Some picketed and marched with signs promoting peace. Others leafletted the workers of Electric Boat. Scott Herrick, a peace activist with a considerable personal fortune, sailed his sloop Satyagraha up and down the Thames River with the words “End the Arms Race; Polaris Action” on its sails. A few boarded the floating dry docks by rowing or even swimming over to talk to workers on the job and to hold “vigils of conscience.” Despite the signs around these facilities threatening a fine of up to $10,000 or 30 years in prison for trespassing, as well as the resignation of one research director as a result of the protesters’ arguments, no trespassers ever got arrested. And now summer was over, and Polaris Action hadn’t ended in the spectacular, highly publicized arrests that they had expected. So the three men at the Hygienic Restaurant -- Bradford Lyttle, Scott Herrick, and Julius Jacobs -- discussed what to do next. The anti-nuclear project here in New London-Groton was shaping up to be a long-term campaign; Bob and Marj Swann (who would later be founders of VPT) had recently committed to continuing with it. Lyttle, Herrick, and Jacobs were restless for the adventure and high drama of the next big action, and felt that the future of Polaris Action was in good hands without them. But where to go next? Brad Lyttle proposed taking up the challenge presented to them by so many Electric Boat workers: “Buddy, you’re in the wrong place. Go and talk to the Russians.” The three men knew of only one other attempt by Western peace activists to demonstrate in a Communist country. From July to November, 1951, Ralph DiGia, Bill Sutherland, Art Emery, and Dave Dellinger (later to be one of the Chicago Seven) attempted the Paris to Moscow Bicycle Trip for Disarmament. The trip was sponsored by the Peacemakers, who also provided training workshops in nonviolent action during Polaris Action. The three made it as far as the Soviet Army headquarters at Vienna before being turned away, but not before leafleting many soldiers and civilians. There was good reason to think the Communist countries would welcome the Western pacifists this time. The three men, working with CNVA, would organize the walk with more support, more participants, and more publicity. The Communist world had already established the World Peace Council, which primarily argued that the Communist governments were peaceful and that the Western capitalist countries were the aggressors. Lyttle had already been arrested in the US for protesting the Atlas nuclear missile. Herrick and Jacobs had risked life and freedom for protesting the Polaris submarines, backbone of the new US nuclear naval policy. By the time the walkers got to Eastern Europe, the whole world would be watching. It would make bad propaganda for the Soviets if they mistreated these high-profile pacifists. No peace walk of this scale had ever been attempted before. The last record was the 125-mile stretch from New York to New London: the one held a few months previously that had brought Jacobs and so many other Polaris Action participants to New London in the first place. Previous walk speeds averaged 15 miles/day up to 21 miles/day. The route they eventually settled on would require an average of 23 miles/day, covering roughly 6000 miles in 10 months if they wanted to reach Russia before winter. They would start on December 1 in San Francisco, head south for the winter to leaflet military industries around Los Angeles, then east to the Titan missile bases in Arizona and New Mexico, as well as the Strategic Air Command bases in New Mexico and Texas. As early spring arrived, the group would head north to Chicago, then east to Cleveland and southeast to Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C. After one more swing up northeast to Baltimore, Wilmington, Philadelphia, and New York City, they would fly to the UK and proceed on through Europe. Word spread quickly. Participants were organized into eight “Team” members who would walk the entire route, and various “supporters” who would join temporarily. All participants had to agree to a “Discipline” to maintain safety and order. Specific slogans for signs were decided upon in advance, as well as iconography: notably, the walkers decided to prominently feature the circular nuclear disarmament symbol which had only been invented two years earlier in the UK. (Story of the nuclear disarmament / peace symbol here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/voluntownpeacetrust/permalink/10157689009237978) As with any such organizing effort, all of this needed money and support. The men were confident that thousands of dollars could be raised at meetings and events after the participants had succeeded and returned home, but they needed funding to start. The proposal that the three men presented to CNVA required a budget of about $54,000 for transportation, food, equipment, communication, salaries and office overhead expenses for support staffers. Among the needed equipment were boots, winter clothes, rain protection, a gas stove, lanterns, pots & pans, groundcloths, first aid / snake bite kits, a flare gun to signal in case of an emergency, and sign frames, much of which would be loaded up in Herrick’s 1955 De Soto station wagon -- the walkers would go on foot, but most of their provisions and gear would be driven for them. All of this would come to be supplemented by “Gifts in kind and hospitality… donated in incalculable amounts” along the walk itself. The peace movement had perennial financial issues, but after Herrick proved his commitment by personally pledging $6000, the CNVA Executive Committee agreed to sponsor the walk in early November. For the next few weeks, Lyttle, Herrick, Jacobs and supporters worked furiously to organize enough to make the December 1 start date. Funds were raised via appeals to the CNVA mailing list, at rallies, and in private conversations. The average contribution was $8; the highest was Herrick’s $6000. At some point, Hilary Harris Films, Inc. decided to accompany the walkers with cameras and their own equipment in a Volkswagen minibus -- they had already shot footage that would become Polaris Action, and the footage they would get on the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace would make up the 1962 documentary The Walk. Word continued to spread, and the organizers continued to reach out to other peace organizations and sympathizers along the planned route for assistance in the walk. As a result, volunteers continued to sign up to help secure donations as well as churches and private residences for the walkers to stay the night. The American Friends Service Committee and Acts for Peace in Berkeley, in particular, helped to organize support for the walkers. Bob Pickus, director of Acts for Peace in Berkeley, organized a send-off including a press conference for the participants, which by his own estimation was the best press conference about pacifism in Berkeley ever up to that point. On December 1, the eight Team participants set off from San Francisco, determined to walk to Moscow. Renowned pacifist A.J. Muste wrote two pieces to promote the project. Here is the first, “The Walk’s Meaning,” in its entirety: Readers will, we think, readily see the symbolism involved in this project. That people are stirred by seeing pacifists who walk for peace has often been proved in this country and abroad. This is a walk across two continents. The message of unilateral disarmament will, by means of this walk across the US and Europe, reach great multitudes, suggesting that peace recognizes no national boundaries; the call for unilateral disarmament goes out to all people. If by next spring, as is very likely, a serious effort to supply NATO with Polaris missiles is under way, West European pacifists will certainly welcome support from US pacifists who have practiced direct action and civil disobedience here, and our walk will be coordinated with their efforts. In particular, we who have, through many projects over a number of years, called for unilateral action by the US, now show that we are prepared to exert every effort to bring that message also to the government and people of the Soviet Union. Sources: “Anti-war activists march to Moscow for peace, 1960-1961.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/anti-war-activists-march-moscow-peace-1960-1961 Lyttle, Bradford. You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. Greenleaf Books, Raymond, New Hampshire: 1966. “Pacifists Picket Atomic Submarines in a Rowboat.” The New York Times. August 26, 1960. https://www.nytimes.com/1960/08/26/archives/pacifists-picket-atomic-submarines-in-a-rowboat.html (pdf version available upon request) Polaris Action. Hilary Harris Films, Inc. 1960. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WjEXGm5hx4 “Timeline of a Life of Activism.” Ralph DiGia Fund for Peace & Justice. http://www.ralphdigiafund.org/life-work-of-ralph-digia/timeline/ After decades of Native and allied activists raising the consciousness and educating the public about the myths and truths about early European colonization of the Americas, starting in June of this year, Christopher Columbus statues started to topple all across the United States. Less than three decades ago, such a trend would have been unimaginable. In fact, during the 1992 “celebrations” of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ first transatlantic voyage, activists in eastern Connecticut focused their efforts not on the removal Columbus statues, but on another target: Captain John Mason, “Conqueror of the Pequots.” The colonial leader’s 9-foot tall, 2-ton heroic bronze statue stood for more than a century in Mystic, CT over the place where he led the massacre of 400-700 Pequot people of all ages and genders, mostly noncombatants. In the end, the Pequot leadership was assassinated; the Pequot name was forbidden; and the roughly 200 survivors were hunted down and either taken in by their former Native rivals, the Mohegans and the Narragansetts, or else enslaved by the English and sold to far away places. In simplified terms, the Pequot survivors who were taken by the Mohegans to the west became the Mashantucket Pequots, and the ones taken by the Narragansetts to the east became the Eastern and Eastern Paucatuck Pequots.

(To learn the story of the massacre itself, please visit the websites for the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center as well as the Battlefields of the Pequot War project.) The efforts to remove or relocate the John Mason statue that began in 1992 was not the first such attempt. Year earlier, starting in the 1970s and continuing into the mid 1980s, Raymond Geer of the Paucatuck Eastern Pequots led an attempt to remove the Mason statue, but did not gain much traction at the time. The Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Tribal Nation was only granted federal recognition in 1983, very narrowly having almost lost the entirety of their reservation land to the State of Connecticut a few years earlier. The Eastern Pequots and Paucatuck Eastern Pequots, two separate groups, unified and became recognized by the Department of Interior in 2002 -- only to have that recognition revoked in 2005 due to fears of a new possible casino on reservation land. In the 1970s-80s, indigenous groups such as the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the United American Indians of New England began publicly challenging the racist assumptions inherent to Columbus Day and Thanksgiving, but the full effects of those consciousness-raising campaigns would not be felt for years. In this period, the Pequot population that lived on reservation land was growing but still quite tiny. Geer had few allies to turn to when he made his attempts against the Mason statue, and this first attempt failed. But by the 1990s, changes in the broader culture were apparent. The recently federally-recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation completed phase 1 of the planned Foxwoods Resort Casino in 1992. Columbus Day “celebrations” were held across the country for the 500th anniversary just as more Americans than ever before started to realize the problems with honoring a figure like Columbus. And in that same year, Wolf Jackson of the Eastern Pequots asked the Southeastern Connecticut Coalition for Peace and Justice (SCCPJ), which had initially formed to oppose the First Gulf War, to help renew the campaign to remove the Mason statue. This time, the effort was built on alliances. The SCCPJ itself was composed of diverse groups including the Catholic Diocese of Norwich, Veterans for Peace, and the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. Wolf Jackson and the CCPJ circulated a petition that summer about removing the statue, which collected over 900 names agreeing that the statue is “an inappropriate commemoration of a massacre of over 700 men, women, and children and represents a distortion of history which is extremely offensive to many citizens, particularly Native Americans.” At first, none of the councils of the three Pequot tribal nations would officially endorse the move, despite the common opinion of Pequots that the statue was offensive. Complicating matters was the bitter rivalry between the Pequot tribes, especially between the darker-skinned Eastern Pequots and the lighter-skinned Paucatuck Eastern Pequots, that made forming a united front very difficult. But after two years of building alliances and healing old wounds, cultivating community support and exploring many possible options for compromise, the demand to remove the statue spread to more people and became impossible to ignore. The petition was presented to the Town of Groton, where there were allies on the Town Council. Despite the growing demand to remove the statue, a descendant of John Mason spoke in favor of keeping the statue on the massacre site. By then, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, suddenly a big player in Connecticut politics, had ended their initial silence and proposed not just the removal of the statue, but its relocation to the in-development Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. The Mashantucket Pequots even offered to pay for the statue’s removal, relocation, and storage while the museum was being built. The Town of Groton ultimately voted to follow the Mashantucket Pequot proposal, but the lawful owner of the statue, the State of Connecticut, instead moved it to Windsor, Connecticut, one of the towns John Mason founded. In May 1995, supporters of the campaign gathered at the statue’s location to witness its removal. The ceremony was one of Native unity and community power. Present were Pequots from all three tribal nations; Mohegans and Narragansetts descended from the old Pequot enemies; and members of SCCPJ and the neighborhood community. Rick Gaumer, SCCPJ member and a former resident of the Voluntown Peace Trust in the late 1970s, was in attendance of the ceremony. After working for the removal of the statue, he discovered that he was a descendant of Nicolas Olmstead, a soldier who followed John Mason’s command to burn the village. Rick spoke at the ceremony, describing how the burning of villages in Vietnam had made him a pacifist, bringing him to this place. A year later, the town of Windsor celebrated the “return” of their hometown founder. It was a solution that Wolf Jackson said he “could live with.” Now, the old question of what to do with the problematic statue is haunting Windsor. The statue has been a target of vandalism since it was moved to Windsor, and the most recent act of vandalism occurred within the last few months. On September 7 of this week, the Windsor Town Council voted 5-4 to take it down from its prominent position at the Palisado Green and move it to the Windsor Historical Society -- a decision difficult to imagine without the momentum of the many recent successes taking down Columbus statues right behind it. When Raymond Geer made his attempt to remove the John Mason statue in the 1970s and 80s, perhaps his society was not quite ready to hear him out. But within a decade or so, things in eastern Connecticut began to change. The 500th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas heightened the attention and scrutiny paid to colonial history, and raised consciousness of the European invasion that led to the genocides of indigenous peoples. The successes of the Mashantucket Pequots and other Native groups along with the 500th Columbus anniversary created a unique cultural moment in eastern Connecticut in the early 1990s -- a moment that Wolf Jackson and the SCCPJ used effectively to complete their campaign. The 400th anniversaries of the founding of Jamestown (1619) and the landing of the Mayflower (1620) have similarly focused some people’s attention on the violent realities of White supremacy and capitalism, bringing coalitions of people together who are now removing statues and dispelling historical myths. Like Wolf Jackson and the SCCPJ, our present challenge is to use our own cultural moment -- and together create a more just society. Sources: “1637 - The Pequot War.” The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. https://www.colonialwarsct.org/1637.htm Gaumer, Rick. “Reminder of the violence that founded a nation.” The Day. July 20, 2020. https://www.theday.com/article/20200720/OP03/200729992 Goode, Steven. “State will move John Mason statue and take it to historical society; monument honored colonial leader of attack on Pequots.” Hartford Courant. September 9, 2020. https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/city-officials-discuss-removal-of-controversial-statue-in-windsor/2301219/ “The History of the Pequot War.” Battlefields of the Pequot War. http://pequotwar.org/about/ Libby, Sam. “For one Pequot, statue’s removal is vision come true.” Hartford Courant. May 11, 1995. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1995-05-11-9505110513-story.html Libby, Sam. “THE VIEW FROM: MYSTIC; An 1889 Statue Leads to Second Thoughts About a Battle in 1637.” The New York Times. November 29, 1992. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/29/nyregion/the-view-from-mystic-an-1889-statue-leads-to-second-thoughts-about.html Libby, Sam. “Where a Statue Stands Is State’s Decision.” The New York Times. July 24, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/24/nyregion/where-a-statue-stands-is-states-decision.html Louie, Vivian and Sam Libby. “Groton Statue Stands at Center of Debate.” Hartford Courant. October 4, 1992. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1992-10-04-0000111690-story.html “The Pequot War.” The Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Tribal Nation. https://www.mptn-nsn.gov/pequotwar.aspx Purdy, Erika M. “Windsor council votes to remove controversial statue from Palisado Green.” Journal Inquirer. September 9, 2020. https://www.journalinquirer.com/towns/windsor/windsor-council-votes-to-remove-controversial-statue-from-palisado-green/article_6c12a68c-f2b0-11ea-a772-6fc4cbb99145.html Shanahan, Marie K. “John Mason Statue has a Homecoming.” Hartford Courant. June 1996. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1992-10-04-0000111690-story.html “Town Officials Discuss Removal of Controversial Statue in Windsor.” NBC Connecticut. July 12, 2020. https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/city-officials-discuss-removal-of-controversial-statue-in-windsor/2301219/ Underhill, John. “Newes from America; Or, A New and Experimentall Discoverie of New England; Containing, A Trve Relation of Their War-like Proceedings These Two Yeares Last Past, with a Figure of the Indian Fort, or Palizado” (1638). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 37. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/37 A Peace of History

While the rest of the world celebrated the labor of working people on May 1, Americans will observe Labor Day on Monday of next week. But what is it that we will be celebrating, exactly? On May 4, 1886, the Haymarket Affair occurred: a complex incident to which we will return another time. For now, the important thing to know is that violence broke out at a street protest, labor leaders were blamed, and following an openly biased trial, the state executed five of the eight labor leaders in what is now generally considered to be a miscarriage of justice. The entire affair was international news. In 1889, the Second Internationale (a coalition of socialist, anarchist, and labor groups from twenty nations) dubbed May 1 “International Workers’ Day,” co-opting the ancient European spring festival May Day for its proximity to the Haymarket Affair anniversary. Meanwhile, the Haymarket Affair became an important touchstone for many young participants in the socialist, anarchist, and labor movements in the United States as well. As the narrative in the general public gradually became more nuanced and sympathetic -- recognizing the executions as unjust “judicial murder” -- the U.S. government saw the commemoration of the incident as an existential threat. And so by 1894, President Grover Cleveland had thrown his support behind the alternative date in September, purely for anti-socialist/anarchist propagandistic reasons, specifically in an attempt to bury the memory of the workers’ tragedy and stifle the movement. Today’s main story begins in 1986, a century after the Haymarket Affair, and concerns the longest sustained nonviolent action in Connecticut’s history. In the 1940s, workers of the Colt Firearms company in Hartford, CT were finally able to organize a union. Four decades later, at the height of the Reagan era, the Colt company was harassing union members and rolling back gains in blatant efforts to shut down the union. During the four-year-long strike that followed, a number of peace activists joined the struggle in favor of the union workers, despite the inherently violent nature of the products the workers were meant to build. At first glance, this may seem completely self-contradictory, but the pacifists followed a different narrative, a more leftist analysis: under capitalism, the workers do not choose what they build, and are thus better understood as victims of worker-exploitation than as warmongers. President Grover Cleveland helped to bury the story of Haymarket, of the miscarriage of justice that followed, and of the left labor movement that was killed in Chicago. Much of U.S. foreign and domestic policy over the next century would be determined by the same xenophobic, anti-left, and anti-labor prejudices that led to the Haymarket executions. While we recognize the history of injustice perpetrated by the U.S. government against working people, we also recognize their perseverance despite it all. Today, many working class people are on the front lines of this pandemic, struggling for better pay and working conditions while trying to stay healthy. This Labor Day, let us remember and celebrate the heroic struggles of working people of the past, and let us thank and defend working people now. -- The Colt 45: Peace Work with a Union Label May 13, 1986 The Colt Firearms factory has been producing guns since the 1800s, from pistols to Gatling guns and now, M-16 automatic weapons. The Colt name is known worldwide. Workers at Colt have tried to establish a union since the turn of the 20th century, and finally succeed in the 1940s. Now, in 1986, they are in a life or death struggle with a company that will do anything to break their union, United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 376. Colt intends to rollback the gains made over the years by the white, black, and Puerto Rican workforce. “We are not claiming that we are losing money, nor were we basing our proposals on the Company's financial condition,” admits the company’s top negotiator. Colt workers have already been protesting on the inside for more than a year against poor treatment and blatant attempts to bust their union. Led by shop chairman Lester Harding, activists have been disciplined, suspended and fired for nonexistent infractions. In response, they print the names of the fired workers on their shirts, and parade in the plant during break time to communicate their anger. Once the strike begins on January 24 1986, the 1,000 strikers attempt to stop scabs from entering the factory and taking their jobs. Frequent scuffles on the picket line are met with overwhelming force by the city police. There are many arrests during the strike’s first months. At one point UAW leader Phil Wheeler is slapped with inciting a riot, a serious felony charge. The boss at Colt knows that public opinion is important in this fight. He thinks he can sway that opinion with full-page newspaper ads. He harps on the picket line conflicts, laying the blame solely on the strikers. He explains how reasonable his negotiating demands are, and how unreasonable the UAW is. Thanks to the newly formed Labor /Community Alliance, the propaganda falls flat. On May 13 1986, forty-five community activists, elected officials, clergy members, teachers and others converge at the Colt factory on Huyshope Avenue, Hartford. They sit down, blocking the parking lot entrance and the scabs attempting to enter the factory. The group is dubbed the “Colt 45,” an ironic take on the company’s most famous product. The civil disobedience is no picnic. The Hartford Police captain in charge of the cops on the line has been accused of acting against the strikers from the beginning. The workers are proven correct when he quits the police force during the strike and takes a job as the new head of security for Colt. The nonviolent Colt 45 action is only one of many community support events and marches organized during the record four-year struggle. Critical to the strikers’ morale is the solidarity they get from other unions and the city and state lawmakers, who support a successful nationwide boycott of Colt products. In fact, the strike itself is the longest sustained nonviolent action in Connecticut history. Included in the Colt 45 are a number of peace activists. Is this some mistake? No, they say. They issue a public statement signed by many of the most locally prominent anti-war figures, who explain that union jobs are good for families and neighborhoods. They understand that workers have no power to choose what they make in this society. The activists want to build relationships with unions and rank-and-file workers to find common ground and ultimately achieve “economic conversion,” the process by which industry changes to peacetime production. There are only two sides in this fight, and they choose the workers. In 1990, UAW 376 wins big. The company finally gives in after labor court decisions have found that Colt has been a massive law breaker. Workers win $10 million in back pay and benefits. All strikers can return to their jobs. A coalition of the state government, private investors-- and the UAW-- have bought the company. Thirty years later, union veterans, community activists, and college students hold a “commemoration of courage” to celebrate the Colt strikers’ victory. At first, some openly question the event’s purpose: do they really want to remember those hard times? But still, many strikers and their spouses attend. When asked about good memories from their historic strike, they answer “the Colt 45.” (Good Trouble: A Shoeleather History of Nonviolent Direct Action is a riveting chronicle of stories that prove time and again the actions of thoughtful, committed people can change their lives and their country. It is a brisk, inspiring primer for veteran political activists and newcomers alike. Civil Rights struggles. “Fight for $15” strikes. Tenant occupations. LGBT campaigns. Each of the 40-plus examples in good Trouble focuses on the power of organizing and mobilizing, relevant in any context, and serves as an “emergency tool kit” for nonviolent action. Excerpt republished with permission from the author.) Sources: Kohn, Sally. “Why Labor Day was a political move” CNN. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/09/01/opinion/kohn-labor-day/ midtowng. “Knights of Labor” Progressive Historians. https://web.archive.org/web/20070930082656/http://progressivehistorians.com/showDiary.do?diaryId=2041 Thornton, Steve. GOOD TROUBLE: A Shoeleather History of Nonviolent Direct Action. Hardball Press, 2019. https://goodtroublebook.com/ |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed