|

On the gray and rainy morning of December 1, 1960, one hundred and fifty people gathered at San Francisco’s Union Square in excited anticipation: a diverse crowd of students, minor celebrities, the religiously-motivated, and others, along with a couple filmmakers and half a dozen people in news and media. The air was chilly, the wind blustery, and perhaps some in attendance were considering going home when, “As if by Providence, the grey ceiling opened and a stream of sunlight washed the Square as the marchers entered.” After a warm reception and a couple send-off speeches from community leaders, the walkers lifted their signs and strode out. No one, least of all the walkers themselves, knew if they would be admitted into Eastern Europe when they finally arrived, or if they would even find hospitality everywhere in their own country -- volunteers were out establishing contacts to support the Walk in California even as the walkers left Union Square. Thus, as flashbulbs burst from cameras and supporters chatted and laughed as they strode beside, and the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace began its 6000 mile journey.

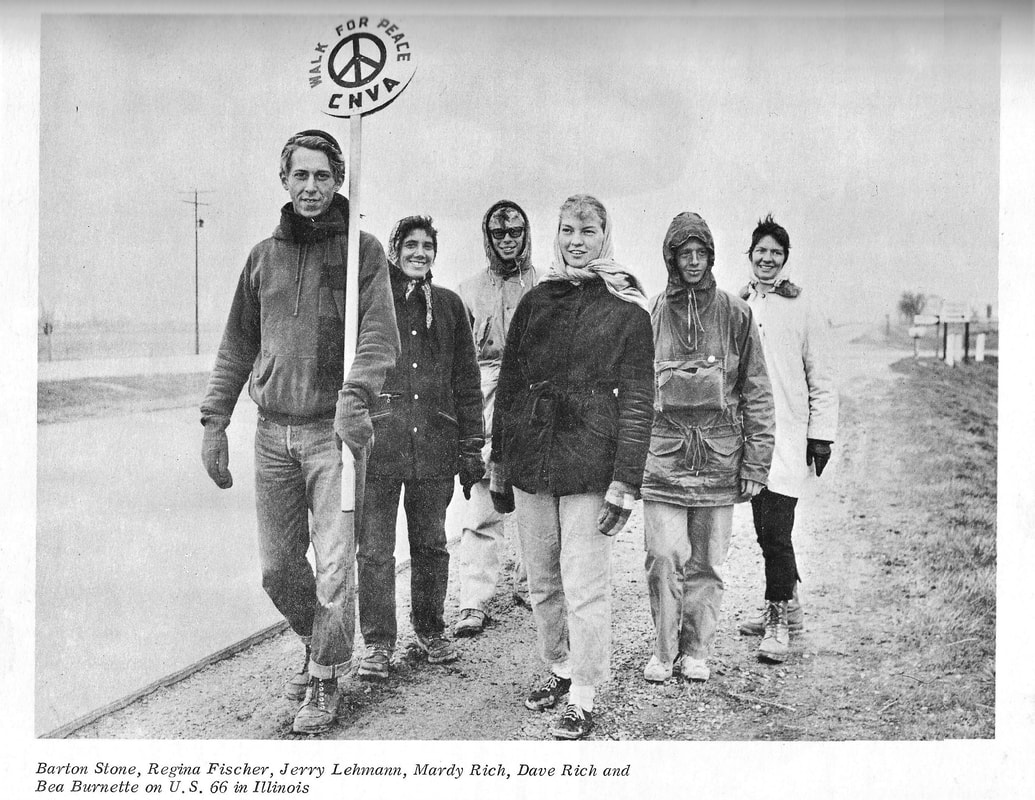

The whole project took a considerable amount of work to organize behind the scenes. So much had to be coordinated: meals, meetings and interviews with the media, rendezvous with local supporters, and especially overnight housing. Bradford Lyttle, one of the principal organizers of the Walk, started the Walk with the others, but eventually found himself zipping on ahead in cars and planes to coordinate. Lyttle especially organized a good amount of media coverage: a 10 minute radio interview here, a two hour radio interview there. Filmmakers even set up an interview between Brad Lyttle and Rand Corporation representative Herman Kahn, who had recently published the book On Thermonuclear War. It took the Walkers the entire first month to cross California and enter Arizona three days behind schedule -- a whole month of learning from painful mistakes and experience. They tested all types of boots and sneakers for walking -- Brad Lyttle estimated that the Walk wore out 200 pairs of shoes. They learned how to treat their blisters, and incorporated foot care into their routine. They learned the physical limits of their bodies, and that almost all of them would have to take the occasional break, at least until their bodies became used to walking an average of 23 miles every day. They learned that sending a car out a few miles ahead of the walkers to talk to the locals sometimes made the difference between free hot meals and empty stomachs. They learned the difference between coordinating in a small town versus a sprawling city: in Los Angeles, organizers had arranged for eight families scattered across the city to host the eight Team members, only to realize the difficulty of coordinating the transportation to each destination in a city like L.A. (especially before mobile phones). Perhaps most importantly, the Walkers learned how to work with each other. This “group of artists, intellectuals, mystics, anarchists and whatnot,” as Lyttle described them, learned to work through differences in opinions and make collective decisions -- despite the “desire for autonomous individuality [which] collides with our need for organization, resulting in relatively complete chaos most of the time.” Brad Lyttle was likely exaggerating about the chaos -- or perhaps he was accurate and it was exactly that creative individuality that also accounted for some of the Walk’s success. The Walk certainly attracted unique people. Bea Burnett was one early convert to the Walk. A corporate spokesperson who had been inspired by marchers at a meeting in San Francisco, Burnett threw herself into the project. At first, she volunteered for the advance work of securing food and housing for the walkers -- in the first week of the Walk, she even convinced local businessmen at a shopping center to give the walkers free lunches and haircuts. Barton Stone, a Buddhist who attended a meeting during the send-off for the Walk in San Francisco, was another early joiner. Others, like John Beecher, an eminent poet and English professor at Arizona State University, and his wife Barbara Beecher, an artist, had been developing their own pacifist feelings for some time, and took the Walk as their opportunity to finally commit to those feelings and do something. At a vigil at the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, ten men and women dressed in white and blue and calling themselves “Children of Light” joined the walkers. On Christmas 1960, Joan Baez showed up and played a short concert for the walkers -- she had visited Polaris Action in New London with Pete Seeger just a few months earlier. Most of January was spent in Arizona, where local receptions were less welcoming. In California, the Walk could usually get a platform, if not a sympathetic audience, at the universities; the worst the walkers would get was mild condescension at what the audience perceived as pacifist naivete. In Arizona, such privileges could not be guaranteed; en route to a speaking engagement organized by sympathetic faculty members of Arizona State University at Tempe, a crowd of over 50 hostile students threatened the walkers with violence if they attempted to proceed toward campus. Even after the marchers convinced the students to let them pass, the audience that ultimately attended the talk heckled and booed the walkers while holding signs like “EXTERMINATE THE ENEMY.” Members of the Team noted the influence of Barry Goldwater, The Arizona Republic, and the John Birch Society, creating a toxic atmosphere of isolationist conservatism and violent paranoia. Even the churches, reliable for a meal or place to spend the night in much of California, largely denied the Walk any help in Arizona. Time and again, advance workers would request assistance from individual church leaders as well as larger religious associations. Quakers and Unitarians were often most likely to answer the call, but it was no less disappointing when other denominations refused them. Some individual ministers who had initially welcomed the walkers even had to reverse their offers out of pressure from their hostile congregations. On the nights they couldn’t find shelter, the walkers camped. Arizona was where the walkers first experienced media blackouts regarding the Walk. In Tucson, a reporter told Team member Scott Herrick that the owner of the main Tucson daily had ordered that the Walk be ignored. Some of this institutional hostility could be explained by individual prejudices of locally powerful men, but the walkers began to suspect that a more coordinated effort might be organizing against them. Reports began to filter in about the FBI spreading rumors and false characterizations about the walkers to local military leaders and law enforcement, sending directives condemning the Walk and suggesting a “hands-off” policy to the media, and warning local chambers of commerce and ministers’ associations not to lend aid. Sometimes, these FBI directives were quite successful. Despite some moments of generosity and humanity along the way, the unfriendly pattern established in Arizona held throughout much of the American Southwest. But some communities perhaps never received the FBI message. When the Walk arrived in Alva, Oklahoma late on the evening of February 21, 1961, the walkers were not expecting what happened that night. From Brad Lyttle’s words about that night: “We had camped at a railroad overpass about a mile north of Alva. Immediately, people began coming to talk to us. There were several ministers who were interested but did not feel we were ‘safe’ enough to take in. Many students came. By the time we finished supper, cars were parked lining both sides of the highway and caused the police a bit of a traffic problem. What a scene. More cars continued to arrive. Our fleet of odd-looking vehicles parked around the green and orange tent, by camp-fire; guitars and singing, foodboxes, lanterns and paraphernalia strewn around. A crowd of fraternity boys parked up on the hill, gathered in a band, with torches. One boy had a bugle, another carried an improvised sign saying WORKERS ARISE. STAMP OUT THIRST. DRINK BEER. They walked yelling and jeering down to the camp, and became part of the crowd. At one time there were about 100 people, mostly students, from Northwestern State Teachers College gathered around our fire, but we must have talked to many more than that, for the crowd kept changing as some left and others came. These students were as a whole much different from others we had spoken to. They were more curious, open-minded, tried harder to understand what we were saying, less antagonistic. I got the impression too they were less informed about world affairs, not as ‘sophisticated’ as, for instance, the students in California. Many of them understood and agreed with us up to the point of taking personal action. They regarded Allan Hoffman and Betty Blanck [two Team walkers] as particularly curious specimens because of their frank atheism. Often they got sidetracked into theological discussions. “There were Five or six groups gathered around nuclei of two or three walkers. People drifted from one group to another. These students asked very intelligent questions which were obviously aimed at understanding, rather than discrediting what we said. “By 12:30 AM most of the crowd had left and many of us fell asleep exhausted. Dr. Beecher said that the last ones didn’t leave until 2:30 AM. He said it was one of the greatest experiences of his life.” Sources: Lyttle, Bradford. You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. Greenleaf Books, Raymond, New Hampshire: 1966. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed