|

On October 20 of last year, Bolivians cast their ballots in their national presidential election. Evo Morales of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party was expected to win, granting him a fourth term to continue the leftist policies that have thus far resulted in impressive economic growth for the country. Crucially, this economic growth has not occurred at the cost of the indigenous poor peoples of Bolivia, as right-wing governments of the past had attempted, but hand-in-hand with the economic and social uplifting of the people of Bolivia. With such socially and economically just policies already working for 14 years, President Morales and MAS enjoyed overwhelming support in the country -- especially among Indigenous and Mestizo peoples, which together constitute the majority of Bolivia’s population. But 21 days later, after the opposition contested the legitimacy of the election results and started targeting MAS party members and their families, chief commander of the Bolivian armed forces General Wiliams Kaliman publicly requested that President Morales resign his position, and Morales soon after fled the country. Right-wing senator Jeanine Anez was then able to declare herself interim president in a move supported by the US government, misconstrued by mainstream Western media to seem more legitimate, and openly joked about by billionaire capitalist Elon Musk who happens to have interest in the country’s lithium supply.

Along with the greed behind the plan to sell Bolivia’s national resources for their own personal short-term gain, we must also consider the coup leaders’ racism. Much has been made of the relatively high number of coups and coup attempts in Bolivian history, and some have attempted to frame the one last year as more of the same in a country that just can never seem to make democracy work. But while it is true that much of the 20th century saw Bolivia wracked in political crises or military dictatorships, the most recent power-grab by the right-wing coalition in the country was the first in over 39 years. It was also the first successful rebellion against the latest Constitution of Bolivia, approved by public referendum in 2009, which defined Bolivia as a unified plurinational and secular (not Catholic, as it was before) country and thereby enfranchised Indigenous groups to exercise local autonomy and participation in government on their terms. As right-wing White descendants of European colonizers, most of the 2019 coup leaders, including Jeanine Anez, had on multiple occasions said out loud, tweeted, or otherwise indicated their sense of racial superiority, disdain for Indigenous cultural practices, and fantasies of violence against Indigenous and Mestizo peoples. The coup leaders clearly identify with the predominantly White global elite over the actual people of their country, evidenced by their desire to privatize and sell off the government-owned industries, reversing the MAS socialist policies which have lifted myriad Bolivians from poverty. But if that were not enough, it is simple enough to find records online of Anez and others in her circle dehumanizing Indigenous and Mestizo Bolivians with terms like “poor Indians” and “satanic.” Indeed, that language is not always meant to be figurative: some, like early coup leader Luis Fernando Camcho, are connected with fascist paramilitary groups like the Santa Cruz Youth Union, which advocates for separation from what they consider a heathen state. As the 2019 Bolivian political crisis developed, many of these fascist paramilitary groups took to the streets. Some may have been involved in violent attacks and arsonry targeted at Morales, MAS members, and journalists. When the right-wing of the country coalesced behind Jeanine Anez and MAS began organizing protests against the new unconstitutional government in response, Anez made Decree 4078, which called on the Bolivian armed forces to assist in “the defense of society and maintaining public order” while exempting such participants from criminal liability. In the subsequent weeks, at least 25 people died of gunshot wounds and two of other causes, while hundreds were injured in clashes with law enforcement. A group of workers organized a march, only to be stopped by soldiers shooting into their ranks and killing nine. Road blockades and mass rallies were attacked by riot police, soldiers, and helicopters with live rounds. MAS, not fully realizing what had happened until it was too late, began negotiating with the new coup government in an attempt to stop the violence. Negotiating with the coup leaders, however, only legitimized the unconstitutional government and temporarily quelled much of the popular resistance. As the negotiations between MAS and the coup leaders continued and the dust settled, protests dissipated, but frustrations grew. The MAS leaders compromised with the coup leaders, and for several months convinced their supporters to accept the new reality. During that time, Anez and her allies have removed Bolivia from multiple international political and economic organizations, expelled people from foreign countries (including the 700 Cuban doctors that provided the foundation for Bolivia’s new free healthcare system), threatened disenfranchisement of largely Indigenous areas, relaxed covid-19 restrictions against the advice of health officials, and privatized key industries in Bolivia. But by July of 2020, after the fourth postponement of the promised new general elections in just 8 months, the people of Bolivia demanded the immediate resignation of Jeanine Anez as well as general elections to be held in September. The Pact of Unity, a national coalition of powerful trade unions and Indigenous groups supporting MAS, called for a general strike and widespread sabotage. Boulders were scattered across highways, trenches dug into rural roads, and mountain passes dynamited -- the number of blockaded roads in Bolivia reaching over 200 in just a few weeks, with some cities completely shut down. The state responded with threats of military repression, and then encouraged right-wing paramilitary groups to attack roadblocks, resulting in dozens injured. Despite the mass rebellion, both MAS and the Anez administration decided to stick with the postponed election date in October. The Bolivian Workers Center (COB), the country’s largest trade union federation, eventually called for an end to the strike, and the Pact of Unity announced the demobilization of protest actions. It may be tempting to think that the protests against the coup in November 2019 and July-August 2020 were inconsequential and ended in failure. The leaders of the trade unions, the Pact of Unity, and even MAS itself gave in to the demands of the coup government on multiple occasions long before popular resistance broke. But it is notable that after the uprising of July-August 2020, the date of the general election was not moved again. The coup government, despite their nominal command of the police and armed forces, was unable to even muster up a final attempt to retain power before the landslide defeat they suffered at the polls a couple weeks ago. The radical popular resistance exhibited across the country by the diverse multitudes of Bolivia reminded their supposed leaders in MAS that such strategies are what put MAS into power in the first place. Perhaps it is easy to say now with the benefit of hindsight, but with 14 recent years of wildly successful socialist economics and decades of organized allied social movements shaping the country, the leftist, progressive, and just forces of Bolivian society are too well-organized and entrenched to be defeated so easily. In the face of such commitment to Bolivian democracy, the long-term viability of Anez’ coup government never stood a chance. Sources: Blair, Laurence and Cindy Jimenez Bercerra. “Bolivia protesters bring country to standstill over election delays.” The Guardian. 9 August 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/09/bolivia-protesters-bring-country-to-standstill-over-election-delays-covid-19-evo-morales “Bolivia begins the week with an indefinite general strike and roadblocks.” Monthly Review Online. 6 August 2020. https://mronline.org/2020/08/06/bolivia-begins-the-week-with-an-indefinite-general-strike-and-roadblocks/ De Marval, Valentina. “Did Bolivia’s interim president delete anti-indigenous tweets?” AFP Fact Check.15 November 2019. https://factcheck.afp.com/did-bolivias-interim-president-delete-anti-indigenous-tweets Ferreira, Javo. “Coup and Resistance in Bolivia.” Left Voice. 12 January 2020. https://www.leftvoice.org/coup-and-resistance-in-bolivia “Healing the Pandemic of Impunity: 20 Human Rights Recommendations for Candidates in the 2020 Presidential Elections in Bolivia.” Amnesty International. 2020. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AMR1828712020ENGLISH.PDF Mackler, Jeff and Lazaro Monteverde. “Bolivia: Anatomy of a Coup.” Popular Resistance. 26 November 2019. https://popularresistance.org/bolivia-anatomy-of-a-coup/ McEvoy, John. “Fear, confusion, and resistance after far-right coup in Bolivia.” The Canary. 12 November 2019. https://www.thecanary.co/global/world-analysis/2019/11/12/fear-confusion-and-resistance-after-far-right-coup-in-bolivia/ Narai, Robert. “Bolivia's right-wing coup government is facing resistance.” Red Flag. 19 August 2020. https://redflag.org.au/node/7329 Snider, Ted. “Morales’s Coup Fits a Long Pattern in Bolivian History.” Truthout. 11 December 2019. https://truthout.org/articles/moraless-coup-fits-a-long-pattern-in-bolivian-history/ Shaw, Danny. “Behind the Racist Coup in Bolivia.” Council on Hemispheric Affairs. 11 November 2019. https://www.coha.org/behind-the-racist-coup-in-bolivia/ In the past week, the internet has been abuzz about the decisive victory Luis Arce and his Movement for Socialism (MAS) party won on October 18. And as well it should: the victory signals the return of democracy to Bolivia after last year’s far-right coup ousted President Evo Morales and other MAS party members from their positions. The internet being what it is, however, some facts and histories have become conflated and unsubstantiated rumors are being repeated as fact. Let us look into the brief history of Bolivia for context as to what happened last October, what happened just last week, and its relevance to the United States.

Bolivia has had a history of political instability and human rights violations particularly perpetrated against Indigenous peoples. Like much of Central and South America, that history begins with the near-complete destruction and subjugation of Indigenous civilizations through Spanish colonization that lasted for about 300 years. In the 19th century, with the European empires in crisis following the Napoleonic Wars, and inspired by the United States and Haitian revolutions against colonial rule, wars of independence were waged successfully across Spanish-American territories (Bolivia is named for the legendary Simon Bolivar, “the Liberator”). But, like in the United States, the pre-existing White male landholding elites led these new nations, with Indigenous peoples in almost every Latin American country designated second-class citizens. This was the case in Bolivia, as well, despite Indigenous people making up the vast majority of the population. Wealthy landowners forced Indigenous people into peasantry to work their estates and mines. The natural resources of the region, silver and then tin in Bolivia in particular, brought foreign investors and trading partners. Meanwhile, conflicts between the elites, seeking to consolidate or carve out some land and power of their own, brought even more violence -- Bolivia lost more than half of its land to neighboring countries in the 19th century following independence. After thirty years of free-market economics that collapsed with the Great Depression in the 20th century, Bolivia followed the shift in much of the world toward greater suffrage. More wars over land and resources were fought, strengthening the importance of the military in Bolivian society. At the same time, political parties like the popular Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR) emerged including persons of Native and mixed descent. Over the course of the 20th century, the Bolivian military intervened in the government on multiple occasions, almost always as right-wing reactions to the success of left-wing politicians and parties. At least one, the dictatorship of General Hugo Banzer from 1971-1978 was materially supported by the United States through CIA Operation Condor, and only brought down when four women started a hunger strike that inspired a national movement of nonviolent resistance. Right-wing coups continued to plague the people of Bolivia as they repeatedly tried to establish a peaceful, lasting democracy, while foreign multinational corporations gradually privatized more of Bolivia’s resources. It was not until the early 2000s, with the Water War of Cochabamba that saw Indigenous people fighting back against the privatization of municipal water, and the Bolivian Gas War over the ownership of the natural gas mines, that a new movement of Indigenous socialist organizations emerged, with labor activist Evo Morales at its head. Morales and MAS campaigned on a promise to finally empower the marginalized groups in the country; when he won the presidency in 2006, Evo Morales became the first Indigenous head of state in South America. Since MAS and Morales took leadership of Bolivia, to the shock and reluctant admiration from the neoliberal western powers, the socialist policies of de-privatization and public ownership of industries have fulfilled that promise, vastly raising the standard of living for the poor, while simultaneously improving the Bolivian economy. According to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, extreme poverty was reduced by half, and the country’s GDP grew by almost 5% per year. So, if things were going so well for Morales and MAS, how did this coup occur? First, for all the good Morales has accomplished -- and the list is impressive -- many leftists believe he probably should have taken a step back at some point to promote (and advise) a new face of his party. In 2016, the results of a national referendum seemed to agree that presidential term limits should be enforced. To many even in his own party, it did not matter that the Supreme Court later struck down the referendum based on the American Convention of Human Rights, and that Morales was legally permitted to run for a fourth term -- his image was already starting to sour. Fast forward to the Bolivian election of October 2019: reasonably assuming that the vast majority of rural Indigenous voters would overwhelmingly choose Morales, MAS declares victory before all the ballots are counted. The right-wing opposition quickly pounced, using the opening to claim manipulation and fraud. The far-right quickly fell in line behind notoriously racist legislator Jeanine Anez, who declared herself interim president. The police turned on Morales, killing dozens in street protests with Morales supporters. And it was not just Bolivians who were mobilized. An entire machine of anti-Morales propaganda aimed at audiences outside of Bolivia appeared seemingly overnight. The Organization of American States (OAS), which was originally established during the Cold War specifically to prevent the rise of democratically-elected leftist governments like MAS, almost immediately claimed to have “deep concern” (at first without evidence) that cast further doubt on the election results. Over a million tweets seemingly from Bolivian accounts claimed to the world “there is no coup.” And the vast majority of American mainstream media fell for the racist, historically ignorant, and simply inaccurate narrative of a corrupt and anti-democratic Latin-American “strongman” finally being removed, even refusing to call it a “coup” at all: the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, and even non-American liberal sources like the Guardian. Morales, his family, and others in his party were threatened with kidnappings, assassinations, and more. Morales fled to Mexico, and many others went into hiding. But it later turned out that the OAS had fabricated any evidence of election tampering, and those tweets came from a massive bot network created by one US Army veteran and apparent right-wing troll Luis Suarez. The mainstream media was either racist, lazy, and/or simply expressing their neoliberal ideologies. And then there’s the tweet from Elon Musk. Last year, as the internet blew up over the Bolivian election crisis, in an example of what some call “saying the quiet parts out loud,” the celebrity billionaire incredibly announced his naked hostility to democracy when it suits the interests of capitalists like himself. Being accused of conspiring with the United States government to organize the coup against Morales in order to obtain lithium from the country, Musk flippantly responded: “We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.” In the year since the coup, the right-wing government under Anez has allegedly kidnapped, murdered, and imprisoned MAS supporters in an effort to stamp out leftist politics in Bolivia. Less than a month after declaring the presidency for herself, and just a week after the military fired massacred at least 23 pro-Morales protesters during a nonviolent demonstration, Anez made Decree 4078 granting impunity for human rights violations committed by the Bolivian Armed Forces in maintaining “public order.” Well, as MAS returns to power in Bolivia, with citizens decisively siding against the right-wing anti-democratic conspirators, many on the internet have dug up the old tweet, along with those claims that Musk himself, or at least the United States government was involved in organizing the coup. Despite some overtures from the Anez regime to foreign businesses to buy up Bolivia’s lithium (including to Musk), the hard evidence of collusion is scant, and mostly conjecture. The troll Suarez seems to have been a lone actor, and no hard evidence has emerged that the conspirators in Bolivia received material aid from the United States. Admittedly, the false claims repeatedly promoted by the OAS are difficult to ignore, especially considering President Trump’s personal support of the coup, as well as the explicitly leftist reasons for the existence of OAS -- but spreading propaganda and misinformation is not necessarily evidence of a premeditated conspiracy. Indeed, the fact that the OAS could not produce any evidence, even faked evidence, for weeks after announcing their “deep concern” indicates that the Bolivian coup was a happy accident for the OAS to take advantage. Regardless of who organized the coup, many of the people who fanned the flames, especially outside of Bolivia, were based in the United States. Anti-democratic sentiments are exposing themselves with greater confidence -- just look at that Musk tweet. As the world’s premier “democracy,” last Cold War-era super power, de facto empire, and “leader of the free world,” we are in the strange position that what happens here has an outsized effect in the world. When we go to vote in a couple weeks, we must also consider the racist right-wing violence and undemocratic policies promoted by our own leaders -- there is more at stake than just the future of the United States. Sources: “Bolivia: Jeanine Añez must immediately repeal decree giving impunity to Armed Forces personnel.” Amnesty International, 18 November 2019. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/11/bolivia-derogar-norma-impunidad-fuerzas-armadas/ Chocquehuanca, David and Bruno Sommer Catalan. “Bolivia’s Socialist VP Candidate: “‘The Coup Against Evo Morales Was Driven by Multinationals and the Organization of American States.’” Jacobin, 26 January 2020. https://jacobinmag.com/2020/09/bolivia-elections-david-choquehuanca-mas-morales Derysh, Igor. “‘Cyber Rambo’: How a US Army vet aided the right-wing coup in Bolivia.” Salon, 23 January 2020. https://www.salon.com/2020/01/24/cyber-rambo-how-a-us-army-vet-aided-the-right-wing-coup-in-bolivia/ Johnston, Jake. “Data from Bolivia’s Election Add More Evidence That OAS Fabricated Last Year’s Fraud Claims.” Center for Economic and Policy Research, 21 October 2020. https://cepr.net/data-from-bolivias-election-add-more-evidence-that-oas-fabricated-last-years-fraud-claims/ Lambert, Renaud. “Bolivia’s coup.” Le Monde, December 2019. https://mondediplo.com/2019/12/02bolivia Macleod, Alan. “Why the Bolivia coup is not a coup — because the U.S. foreign policy establishment wanted it.” Salon, 13 November 2019. https://www.salon.com/2019/11/13/why-the-bolivia-coup-is-not-a-coup-because-the-u-s-foreign-policy-establishment-wanted-it/ “Massacre in Cochabamba: Anti-Indigenous Violence Escalates as Mass Protests Denounce Coup in Bolivia.” Democracy Now!, 18 November 2019. https://www.democracynow.org/2019/11/18/bolivia_cochabamba_massacre_anti_indigenous_violence Robinson, Nathan J. “Lessons From The Bolivian Coup.” Current Affairs, 26 November 2019. https://www.currentaffairs.org/2019/11/lessons-from-the-bolivian-coup Rozsa, Matthew. “Elon Musk becomes Twitter laughingstock after Bolivian socialist movement returns to power.” Salon, 20 October 2020. https://www.salon.com/2020/10/20/elon-musk-becomes-twitter-laughingstock-after-bolivian-socialist-movement-returns-to-power/ Wilgress, Matt. “The Far-Right Coup in Bolivia.” Jacobin, 14 November 2020. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/11/bolivia-coup-evo-morales-jeanine-anes-indigenous-violence [Content Warning: mention of extreme cruelty and violence, human rights abuses]

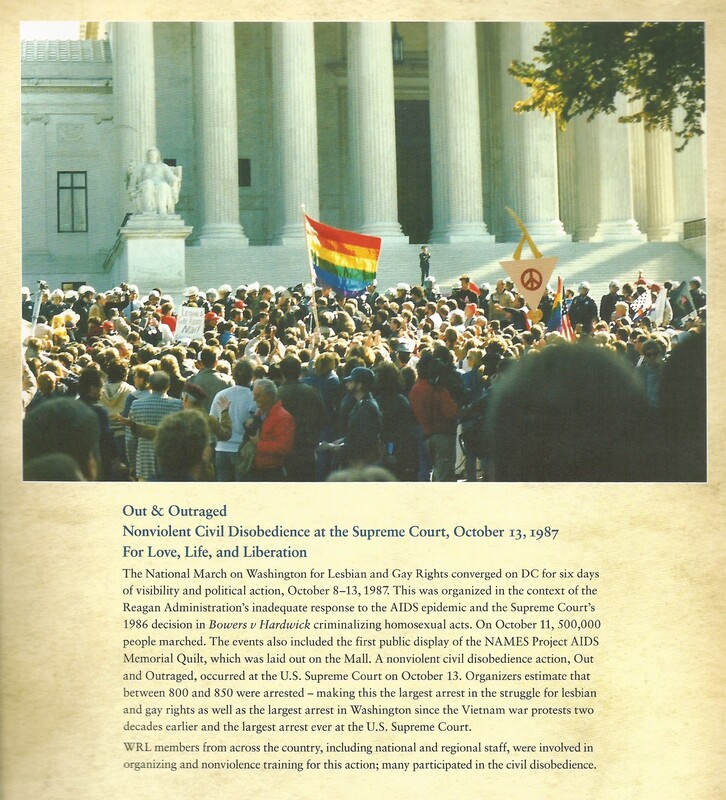

In 1987, Argentine military leaders started the Carapintada Mutiny against the relatively new civilian government, attempting to evade accountability for human rights violations perpetrated under the previous government. Argentina had suffered political instability throughout much of the 20th century, including multiple military coups, and this mutiny seemed to be the start of another powergrab. But the attempt failed, defeated not by the superior leadership of the civilian President Raul Alfonsin, but snuffed out by overwhelming numbers of citizens on the streets demanding an end to the violence and military rule once and for all. In 1976, a right-wing military junta supported by US Operation Condor seized power in Argentina and terrorized the country for the next seven years in what the junta itself called the Dirty War. Drawing its authority in part from a secret decree from the previous government, the National Reorganization Process, or Proceso, removed President Isabel Peron, suspended Congress and the Supreme Court, imposed strict media censorship, and banned all political parties and unions. With all checks on power removed, the Proceso sent military and right-wing paramilitary death squads to torture and massacre or otherwise disappear an estimated 10,000-30,000 people over seven years. Victims included anyone suspected of being a guerrilla, trade unionist, leftist, or other dissident of either the Proceso or the neoliberal economic policies of Operation Condor. The regime also disappeared hundreds of pregnant women, murdering them after giving birth and distributing their children as spoils of war: some were raised in new families, others abandoned, and still others sold into human trafficking. The Proceso only came to an end in 1983 after mismanaging the economy and permitting widespread corruption for years, suffering a humiliating defeat in the failed invasion of the Islas Malvinas (AKA the Falkland Islands), and being pressured by the international community to reinstate democratic processes. In fact, it was the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, women whose pregnant daughters had been disappeared, who were largely responsible for bringing global attention to the atrocities. Under pressure from all sides, the military junta permitted open elections in 1983, and the centrist candidate Raul Alfonsin won on a platform to bring the perpetrators of human rights abuses to justice. Shortly after taking office, President Alfonsin launched the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons. After a year of research, in September 1984, the Commission produced the “Nunca Mas” (Never Again) report detailing thousands of deaths and disappearances under the Proceso. The Trial of the Juntas officially began in April 1985, seven months later. The trials were gradual and methodical, and many who were to stand trial retained their positions in the military in the intervening years. In the meantime, anxiety grew among those who had perpetrated the state-sponsored atrocities of the Dirty War. In 1986, the military successfully pressured President Alfonsin and the National Congress under threat of a coup to pass the Full Stop Law, which effectively granted immunity for the atrocities the Commission was meant to investigate. Even still, on April 15, 1987, Major Ernesto Barreiro was called by civilian court subpoena to answer for allegations of torture and murder as chief torturer at the La Perla concentration camp. Barreiro refused to comply, instead taking refuge in the 14th Airborne Infantry Regiment camp at Cordoba with support from the local commander. The mutiny quickly spread to other military bases and barracks. Soon, the Carapintadas (“Painted Faces”), so-called for their military camouflage, demanded amnesty for all alleged human rights violations as well as a change to the military authority. President Alfonsin waffled on his response to the rebellion -- flatly refusing to negotiate at first, then later insisting on a compromise for “all the major political parties.” He even went on at a separate public address to call the mutineers “heroes of the Malvinas war,” a comment met with derision from the audience. Indeed, apparently dissatisfied with the government’s ambivalent response to the mutiny, Argentines themselves took action. Just two days after Barreiro’s subpoena refusal, about 500 civilians marched onto the Cordoba base, defying a tank placed there to intimidate them, and forced the surrender of the 80 officers there. Thousands more citizens besieged the Campo de Mayo facility, an infamous site of human rights atrocities, while 400,000 took to the streets of Buenos Aires in opposition to the coup attempt. The trade union federation called for a general strike, motorists waved Argentine flags and honked in support of protesters, and at least one massive street demonstration was happening in some major city every day. Protesters rallied around slogans: “Nunca mas” and “Long live democracy! Argentina!” Encouraged by the clear opposition to the mutiny by Argentine citizens, President Alfonsin finally took charge. He distributed a document to all the prominent members of Argentine society, asking them to “support in all ways possible the constitution, the normal development of the institutions of government and democracy as the only viable way of life of the Argentines.” Leaders of all the major political parties, civic organizations, labor unions, business groups, and the Catholic Church signed, effectively turning all corners of society against the coup. On April 17, President Alfonsin himself went to the citizen-besieged Campo de Mayo and negotiated the mutineers’ surrender, announcing later “The time for the coups has ended.” The mutiny had been defeated. Or so it appeared. In actuality, the centrist President Alfonsin ultimately gave in to most of the mutineers’ demands. In the weeks after the mutiny, Alfonsin changed the oversight authorities for the military, as the Carapintadas demanded. Alfonsin also passed the Law of Due Obedience shortly after the mutiny, which granted amnesty for subordinates who may have committed atrocities while carrying out orders. Justice regarding Proceso-era atrocities would not be resumed until 2003, when the Full Stop Law of 1986 and the Law of Due Obedience of 1987 were ruled unconstitutional, over 16 years later. The people of Argentina defeated a nascent military coup and saved democracy in their country, but in the process let their ambivalent centrist government betray the very reason for putting down the rebellion in the first place. So let us remember to maintain scrutiny of our legitimate leaders even after illegitimate power-grabs are defeated and democracy is saved, lest we put off justice any longer. Sources: “Argentina: The Full Stop and Due Obedience Laws and International Law.” Amnesty International, April 2003. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/3f13d9d34.pdf Blakemore, Erin. “30,000 People Were ‘Disappeared’ in Argentina’s Dirty War. These Women Never Stopped Looking.” History.com, March 7, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/mothers-plaza-de-mayo-disappeared-children-dirty-war-argentina “Nunca Mas (Never Again): Report of Conadep (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons).” Desaperecidos.org. http://www.desaparecidos.org/nuncamas/web/english/library/nevagain/nevagain_000.htm Zunes, Stephen. Civil Resistance Against Coups: A Comparative and Historical Perspective. ICNC Monograph Series, 2017. https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ICNC-Monograph-Civil-Resistance-Against-Coups.pdf On Sunday, October 11, many of us will celebrate National Coming Out Day. Few, however, know that October 11 was chosen to commemorate the largest demonstration on Washington, D.C. up to that point: the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, AKA “The Great March” of 1987. Between 500,000 and 750,000 participants marched on the National Mall for a number of interconnected issues, not least of all demands for the Reagan Administration to finally acknowledge and address the ongoing AIDS epidemic that was disproportionately affecting men who had sex with men. The March encompassed six days of activities, starting with a mass wedding conducted for 2,000 same-sex couples in front of the IRS building. In many ways, we in 2020 share much with those Americans 33 years ago: a fatal disease spreads unchecked through the population as a far-right government callously and intentionally ignores the danger. But against all odds, in just a single generation, activists and allies rapidly transformed attitudes and policies toward queer people altogether, leading to increased research into HIV/AIDS, the adoption and later repeal of the “don’t-ask-don’t-tell” policy, the legalization of equal marriage, and countless lives saved from disease, homophobic violence, or suicide. And many of those who helped shape the course of our society got their start at The Great March in 1987.

It was a pivotal moment in queer history. The HIV/AIDS epidemic had started in 1981, but had been permitted by the Reagan Administration to absolutely devastate gay communities the entire time. People struggled for years to get help from the medical community, from the government, from anyone -- all while watching their loved ones die. Then in 1986, in the ruling for Bowers v. Hardwick, the US Supreme Court upheld the criminalization of “sodomy” between two consenting men in the privacy of a home. This regressive and outrageous violation of individual privacy spurred a new impetus for people to organize in protest. The group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was one such group to form in this time -- a leaderless organization dedicated to ending the AIDS epidemic through nonviolent direct action: conducting medical research or forcing the government to fund such research, direct treatment of sick people and advocacy for sick people, promoting safe sex and comprehensive sex education, and more. ACT UP played a significant role in The Great March of 1987, featuring prominently in the march itself, the main rally, and the civil disobedience action at the US Supreme Court. It was the first time ACT UP was covered in national news, but it certainly would not be the last -- after participants had returned home, local ACT UP chapters began popping up all over the country, transforming society. Why was the Great March of 1987 so successful? After all, it was the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights -- what made this second one so much more successful than the first? The first march was held in 1979, ten years after the Stonewall Riots and a year after the assassination of Harvey Milk. Big names were in attendance: Allen Ginsberg, Audre Lorde, Congressman Ted Weiss, and more. The National Steering Committee mandated gender parity and 25% representation of people of color. A few other groups were contacted to support the March: Lambda Legal Defense Fund, National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, the National Organization of Women (NOW), and the National Gay Task Force. Organizers agreed upon a few specific demands unique and inclusive to all lesbian/gay people. Despite all that, only 75,000 to 125,000 participants attended -- a relatively small crowd compared to many other marches of the past couple decades. What’s worse, the event did not seem to inspire participants by and large to organize and take action on their own. By 1987, the situation had changed dramatically. The HIV/AIDS crisis in the United States started in 1981, two years after the first march. In the first six years, at least 1,920 people had died from AIDS, each one represented by a 3 ft by 6 ft panel of the AIDS Memorial Quilt first presented on the National Mall during The Great March, and the number was rising unchecked; when the Quilt was laid out for the first time, it covered an area larger than a football field. President Reagan himself did not publicly utter the word “AIDS” until well into his second term, and intentionally ignoring the crisis had become a de facto policy. But in the intervening years, queer activists had linked up with other social movements, learning from more experienced groups and coming to recognize the commonality of their oppressions. In preparation for The Great March, a new list of demands was made that included not just legal protection for people in homosexual relationships nor the mere repeal of all anti-sodomy laws, but also included a demand to end discrimination against persons with HIV/AIDS (regardless of sexual ortientation), a demand for reproductive freedom, and a demand for an end to racism in the United States and apartheid in South Africa. In the months of organizing leading to The Great March, queer activists contacted not just big names to participate, but big organizations to endorse this platform. The list of groups endorsing the March in 1987 filled several pages, and included labor unions, civil rights groups, women’s organizations, religious groups, and elected officials at various levels. Cesar Chavez, co-founder of the United Farm Workers and a leading figure in the Chicano civil rights movement, was a keynote speaker. Eleanor Smeal, three-term President of the National Organization for Women, was also a keynote speaker. In a speech at the March, Democratic Presidential candidate Jesse Jackson said, “We gather today to say that we insist on equal protection under the law for every American, for workers' rights, women's rights, for the rights of religious freedom, the rights of individual privacy, for the rights of sexual preference. We come together for the rights of all American people.” In a summary of how this new LGBTQ+ movement connected to other social movements, Chicago Mayor Harold Washington wrote in his endorsement letter, “The breadth of the issues highlighted by the March -- against racism and apartheid, as well as for civil rights -- is consistent with the historic thrust of struggles for civil rights in this country.” Indeed, the March in 1987 was one the first times the LGBTQ+ movement exercised another American tradition: mass civil disobedience. Three days into the activities, ACT UP led the nonviolent action “Out & Outraged” in which activists attempted to enter the US Supreme Court to demand the reversal of the decision in Bowers v. Hardwick. Although the scene may have appeared chaotic to some, ACT UP had previously learned certain organizing practices from groups like the War Resisters League in order to safely and effectively perform actions -- some practices that many other groups still use today. For example, every participant was required to be part of an autonomous “affinity group.” This rule meant that no single individual could spontaneously join the action without their group nearby to keep the individual both accountable and safe. It also meant that there was a great amount of trust shared between members of the same affinity group. Affinity groups would be formed months in advance, and members would often train, learn, and work together on the same issues. These best practices in organizing, like the use of affinity groups, helped maintain safety, accountability, and focus while diverse participants carried on potentially dangerous actions. With these practices, the LGBTQ+ movement joined the ranks of more mature, experienced, and successful movements that had already won many successes with the same nonviolent action strategies. Of course, the situation facing us now is not quite the same as in 1987. Because Covid-19 is a sickness of the breath, not the blood, and is thus much easier to spread than HIV/AIDS, we must exercise far greater caution. And yet, when George Floyd was murdered in May, people found ways to express their rage on the streets while staying safe. From 1981 to 1987, the United States tragically lost about 1,920 people to AIDS. The pain of those losses sparked a movement during a deadly epidemic that not only saved countless lives by pressuring a negligent government and speeding up HIV/AIDS research, but also helped to rapidly transform attitudes and policies toward queer people in the United States altogether. Sometimes, it is from pain and outrage that the most transformative movements grow. It’s time to let them come out again. (The image for this post is a part of a collection assembled by Markley Morris, a LGBTQ+ activist and artist involved with War Resisters League, and is featured in the War Resisters League Perpetual Calendar. Full source for the image below. To see more pages from the Perpetual Calendar as well as to order your own copy, follow this link: https://www.warresisters.org/store/wrl-perpetual-calendar If you would like to subscribe to the text-only Google Calendar version of the Perpetual Calendar, follow this link: https://calendar.google.com/calendar/embed?src=i10q0ba7d5vsn857rhopomg98o%40group.calendar.google.com&ctz=America%2FNew_York) Sources: “Affinity Groups & Support.” ACT UP. https://actupny.org/documents/CDdocuments/Affinity.html Butigan, Ken. “LGBTQ everywhere: the power of marching on Washington.” Waging Nonviolence. October 11, 2012. https://wagingnonviolence.org/2012/10/lgbtq-everywhere-the-power-of-marching-on-washington/?pf=true D’Emilio, John. “The 1987 March on Washington Committee: The Chicago Chapter.” Out History. December 21, 2016. http://outhistory.org/blog/in-the-archives-the-1987-march-on-washington-committee-the-chicago-chapter/ “Jim.radke.3” Nonviolent Civil Disobedience at the U.S. Supreme Court, October 13, 1987. http://supremecourtcd.org/Photos.html#38 Springate, Megan E. “LGBTQ Civil Rights in America.” LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History. National Park Foundation, 2016: Washington, DC. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/lgbtqheritage/upload/lgbtqtheme-civilrights.pdf Stein, Marc. “Memories of the 1987 March on Washington - August 2013.” Out History. http://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/march-on-washington/exhibit/by-marc-stein “Wedding, The.” Histories of the National Mall. http://mallhistory.org/items/show/532 Williams, Lena. “200,000 March in Capital to Seek Gay Rights and Money for AIDS.” The New York Times. October 12, 1987. https://web.archive.org/web/20070326092700/http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9B0DE7DA1E3CF931A25753C1A961948260 This past week, activists in Philadelphia made an incredible announcement: the city government had tentatively agreed to turn over 50 vacant homes to a community land trust, ensuring that those homes will remain affordable forever. This historic victory comes after six months of direct action: supported by a diverse network of activists, over 120 people in two homeless encampments protested the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA), while 15 mothers and their children weathered threats of eviction from the formerly vacant homes they had moved into. Activists and organizers at various levels coordinated and sustained pressure on the PHA to lead to this tentative agreement. With over 5000 homeless people in Philadelphia, and with this present deal for the first 50 homes not yet finalized, much more work is still to be done. But the success so far is a model for many other communities seeking to secure permanent affordable housing and equitable economic development -- a model first pioneered by Black farmers on a 5700-acre tract of land in Albany, Georgia in 1969.

The first community land trust (CLT) was New Communities, Inc., organized primarily by civil rights activists in the late 1960s for Black sharecroppers who had lost their homes and jobs for registering to vote. It was an experiment in cooperation and collective resilience in the face of endless challenges. Like the recent efforts in Philadelphia and elsewhere, the creation of New Communities grew out of resistance and necessity -- and so did the movements around the world that inspired the CLT in the first place. Influences include the Gramdan village movement in India organized by Vinoba Bhave, who had worked with Gandhi, as well as the single-tax movement in the United States and the garden city movement in the UK. One key figure in the development of the CLT was Bob Swann, a founding member of the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action (NECNVA; predecessor of the Voluntown Peace Trust), who began to explore “nonviolent economics” when he was in prison as a war resister during World War II. Swann’s major theoretical contribution to the development of community land trusts was to put the “C” in CLT, emphasizing the importance of community control of the land they put in trust. The “Peace Farm” that eventually became the Voluntown Peace Trust was an early experiment in some of Swann’s ideas for an intentional community, but it wasn’t until he began working with Slater King, president of the Albany Movement and a cousin of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Charles Sherrod, an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and others from the civil rights movement that the first community land trust in the United States was born. But what, exactly, is a community land trust? A community land trust (CLT) is a nonprofit corporation that actively acquires, holds, and stewards land for a place-based community, usually in order to provide affordable housing, increase food security, and equitably redevelop neighborhoods. The CLT acquires land with the intention of owning it forever, but any building on that land may be sold to an individual homeowner, a housing cooperative, a rental housing developer, or some other nonprofit, for-profit, or governmental entity. In addition, the CLT may also lease the land on which a building stands to the new building owner in a ground-lease, granting long-term exclusive-use rights to that land and a resale formula which maintains the permanent affordability while allowing limited equity. This means that one may buy, sell, alter, inherit, and even mortgage a building on land owned by a CLT. CLTs are designed to be guided by and accountable to the community that lives in and around it. The size of the community can range from a single neighborhood to an entire county, and all adults who live within the community typically qualify as voting members of the CLT. A board of directors leads the CLT, with members drawn equally from three groups of stakeholders within the community: residents/leaseholders of CLT-owned land, CLT members, and public representatives who can connect to broader constituencies. Many CLTs actively seek to expand their land holdings, including community gardens, civic buildings, commercial spaces, and other community assets. There is a great deal of diversity under the umbrella term of “community land trust.” The fundamental purpose for the CLT, however, is always primarily to secure permanent affordable housing for people with low or moderate income in an equitable way. From its founding in 1969 to 1983, many of the resident farmers of New Communities considered their land trust as a safe haven for other Blacks. The dozen or so residents of New Communities, as well as dozens more participating community members, grew and sold crops, raised and slaughtered hogs, operated a smokehouse, and even built a sugarcane mill. But a combination of systemic racism and bad fortune conspired against them. Racist Whites in the area boycotted their market and otherwise sabotaged New Communities. Blight and bad weather caused financial troubles to mount. Requests for an emergency loan from the federal Farmers Home Administration were consistently denied by local officials, despite the approval of similar requests from neighboring White farmers. Then, starting in 1981, a severe drought devastated the farms of southwest Georgia, exacerbating problems. When finally Washington officials forced local administrators to approve the loans, the assistance New Communities received was consistently too little, too late, and tied to arbitrary restrictions. New Communities persisted for a few years longer, but eventually lost the property to foreclosure in 1985. The residents of New Communities were just some of the victims of the systemic discrimination by the Farmers Home Administration over several years, as was revealed in a national class action lawsuit brought by Black farmers against the FHA in 1997. As one judge wrote later, “In several Southeastern states, for instance, it took three times as long on average to process the application of an African American farmer as it did to process the application of a white farmer.” But the members of New Communities did not disappear, instead continuing to meet regularly even after losing the original property. The case against the FHA was eventually settled, and in 2009, New Communities was awarded $12 million in damages. The community land trust invested the money in a new 1600-acre property named Resora, some miles outside of Albany, GA, to pick up where they had left off all those years ago. After almost two and a half decades, their persistence paid off. New Communities continues to foster and inspire community land trusts across the country and around the world as a model for permanent affordable housing and equitable economic development. They celebrated 50 years of resilience last year, hosting community land trust activists from around the country, supported by Grounded Solutions. Today, more than 330 CLTs exist around the United States, including the Southeastern Connecticut Community Land Trust (SE CT CLT), affiliated with the Voluntown Peace Trust. Sources: Arc of Justice: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of a Beloved Community. Producer/Directors Helen S. Cohen and Mark Lipman. Open Studio Productions. 2016. https://www.arcofjusticefilm.com/ Breed, Allen G. “Black Farmers’ Lawsuit Revives a Dream.” The Washington Post. December 6, 2001. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2001/12/06/black-farmers-lawsuit-revives-a-dream/f286668f-67de-400f-a10b-051ba9bf47a7/ Elliot, Debbie. “5 Decades Later, New Communities Land Trust Still Helps Black Farmers.” National Public Radio. October 3, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/10/03/766706906/5-decades-later-communities-land-trust-still-helps-black-farmers Lacey, Akela. “Philadelphia activists on verge of historic win for public housing.” The Intercept. September 29, 2020. https://theintercept.com/2020/09/29/philadelphia-public-housing/ Mills, Stephanie. On Gandhi’s Path: Bob Swann’s Work for Peace and Community Economics. New Society Publishers. 2010. Further Resources: Black and Brown Workers Cooperative (who led the Philadelphia CLT campaign): http://blackandbrownworkerscoop.org/ Philadelphia Housing Action (latest info from the coalition of groups in the Philadelphia CLT campaign): https://philadelphiahousingaction.info/ New Communities, Inc.: https://www.newcommunitiesinc.com/ More on the history of CLTs: http://cltroots.org/ Video-lecture and slideshow on the history of CLTs: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aC7YRbih4IY&t Southeastern Connecticut Community Land Trust: https://sectclt.org/ |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed