|

[Content Warning: mention of extreme cruelty and violence, human rights abuses]

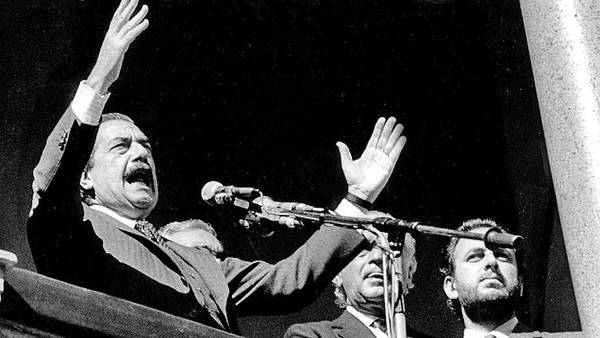

In 1987, Argentine military leaders started the Carapintada Mutiny against the relatively new civilian government, attempting to evade accountability for human rights violations perpetrated under the previous government. Argentina had suffered political instability throughout much of the 20th century, including multiple military coups, and this mutiny seemed to be the start of another powergrab. But the attempt failed, defeated not by the superior leadership of the civilian President Raul Alfonsin, but snuffed out by overwhelming numbers of citizens on the streets demanding an end to the violence and military rule once and for all. In 1976, a right-wing military junta supported by US Operation Condor seized power in Argentina and terrorized the country for the next seven years in what the junta itself called the Dirty War. Drawing its authority in part from a secret decree from the previous government, the National Reorganization Process, or Proceso, removed President Isabel Peron, suspended Congress and the Supreme Court, imposed strict media censorship, and banned all political parties and unions. With all checks on power removed, the Proceso sent military and right-wing paramilitary death squads to torture and massacre or otherwise disappear an estimated 10,000-30,000 people over seven years. Victims included anyone suspected of being a guerrilla, trade unionist, leftist, or other dissident of either the Proceso or the neoliberal economic policies of Operation Condor. The regime also disappeared hundreds of pregnant women, murdering them after giving birth and distributing their children as spoils of war: some were raised in new families, others abandoned, and still others sold into human trafficking. The Proceso only came to an end in 1983 after mismanaging the economy and permitting widespread corruption for years, suffering a humiliating defeat in the failed invasion of the Islas Malvinas (AKA the Falkland Islands), and being pressured by the international community to reinstate democratic processes. In fact, it was the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, women whose pregnant daughters had been disappeared, who were largely responsible for bringing global attention to the atrocities. Under pressure from all sides, the military junta permitted open elections in 1983, and the centrist candidate Raul Alfonsin won on a platform to bring the perpetrators of human rights abuses to justice. Shortly after taking office, President Alfonsin launched the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons. After a year of research, in September 1984, the Commission produced the “Nunca Mas” (Never Again) report detailing thousands of deaths and disappearances under the Proceso. The Trial of the Juntas officially began in April 1985, seven months later. The trials were gradual and methodical, and many who were to stand trial retained their positions in the military in the intervening years. In the meantime, anxiety grew among those who had perpetrated the state-sponsored atrocities of the Dirty War. In 1986, the military successfully pressured President Alfonsin and the National Congress under threat of a coup to pass the Full Stop Law, which effectively granted immunity for the atrocities the Commission was meant to investigate. Even still, on April 15, 1987, Major Ernesto Barreiro was called by civilian court subpoena to answer for allegations of torture and murder as chief torturer at the La Perla concentration camp. Barreiro refused to comply, instead taking refuge in the 14th Airborne Infantry Regiment camp at Cordoba with support from the local commander. The mutiny quickly spread to other military bases and barracks. Soon, the Carapintadas (“Painted Faces”), so-called for their military camouflage, demanded amnesty for all alleged human rights violations as well as a change to the military authority. President Alfonsin waffled on his response to the rebellion -- flatly refusing to negotiate at first, then later insisting on a compromise for “all the major political parties.” He even went on at a separate public address to call the mutineers “heroes of the Malvinas war,” a comment met with derision from the audience. Indeed, apparently dissatisfied with the government’s ambivalent response to the mutiny, Argentines themselves took action. Just two days after Barreiro’s subpoena refusal, about 500 civilians marched onto the Cordoba base, defying a tank placed there to intimidate them, and forced the surrender of the 80 officers there. Thousands more citizens besieged the Campo de Mayo facility, an infamous site of human rights atrocities, while 400,000 took to the streets of Buenos Aires in opposition to the coup attempt. The trade union federation called for a general strike, motorists waved Argentine flags and honked in support of protesters, and at least one massive street demonstration was happening in some major city every day. Protesters rallied around slogans: “Nunca mas” and “Long live democracy! Argentina!” Encouraged by the clear opposition to the mutiny by Argentine citizens, President Alfonsin finally took charge. He distributed a document to all the prominent members of Argentine society, asking them to “support in all ways possible the constitution, the normal development of the institutions of government and democracy as the only viable way of life of the Argentines.” Leaders of all the major political parties, civic organizations, labor unions, business groups, and the Catholic Church signed, effectively turning all corners of society against the coup. On April 17, President Alfonsin himself went to the citizen-besieged Campo de Mayo and negotiated the mutineers’ surrender, announcing later “The time for the coups has ended.” The mutiny had been defeated. Or so it appeared. In actuality, the centrist President Alfonsin ultimately gave in to most of the mutineers’ demands. In the weeks after the mutiny, Alfonsin changed the oversight authorities for the military, as the Carapintadas demanded. Alfonsin also passed the Law of Due Obedience shortly after the mutiny, which granted amnesty for subordinates who may have committed atrocities while carrying out orders. Justice regarding Proceso-era atrocities would not be resumed until 2003, when the Full Stop Law of 1986 and the Law of Due Obedience of 1987 were ruled unconstitutional, over 16 years later. The people of Argentina defeated a nascent military coup and saved democracy in their country, but in the process let their ambivalent centrist government betray the very reason for putting down the rebellion in the first place. So let us remember to maintain scrutiny of our legitimate leaders even after illegitimate power-grabs are defeated and democracy is saved, lest we put off justice any longer. Sources: “Argentina: The Full Stop and Due Obedience Laws and International Law.” Amnesty International, April 2003. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/3f13d9d34.pdf Blakemore, Erin. “30,000 People Were ‘Disappeared’ in Argentina’s Dirty War. These Women Never Stopped Looking.” History.com, March 7, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/mothers-plaza-de-mayo-disappeared-children-dirty-war-argentina “Nunca Mas (Never Again): Report of Conadep (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons).” Desaperecidos.org. http://www.desaparecidos.org/nuncamas/web/english/library/nevagain/nevagain_000.htm Zunes, Stephen. Civil Resistance Against Coups: A Comparative and Historical Perspective. ICNC Monograph Series, 2017. https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ICNC-Monograph-Civil-Resistance-Against-Coups.pdf Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed