|

For many, the end of the year is the time for being sociable, visiting friends and family, living in the present — but it’s also time for quiet reflection and planning for the future. This is as true for the activist as it is for the average person. At the end of 1972, a CNVA member living at VPT penned the following poem that expresses much of this balance between introspection and sociality — reflecting on the organization’s recent accomplishments and next steps to complete; on the tranquil solitude of VPT in wintertime interspersed with flurries of guests and activities; on the deep and wide connections this little group of antiwar activists had made in their area and across the country over the last decade; and on the ways in which these people formed genuine relationships and communities within and apart from the work. As the winter blues start up, it helps to remember that even a small group in sleepy old Voluntown can become a critical part of a mass movement. Happy a safe and happy new year. -- —

Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source Lynn. “Back at the Farm.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 30 December 1972 (Bulletin #129), page 4. “Christmas Week Training and Study Course in Nonviolent Direct Action and Peace Education” (1961)12/24/2022

For many, Christmas means taking time off from work and relaxing. For others, it’s all about spending time with family. But for Connecticut peace activists of the 1960s — perhaps inspired by the radical nonviolent resistance of Christ himself — Christmas was time for training. During the week after Christmas in 1961, the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action sponsored a four-day training and study course in New York City to teach their tactics and skills. This training course, and others like it, were responsible for spreading many of the protest methods and philosophies that the era has become known for. As shown in the “Tentative Schedule,” the organizers of the training were concerned not just with how one should protest, but also with why one should protest in certain ways — namely, nonviolently and with direct action. Much of the time would also be spent on learning and developing practical skills, such as writing leaflets and press releases. Moreover, the whole curriculum included multiple moments to reflect on recent history, current events, and both global and local issues. In fact, an early version of the “think global, act local” ethos can be seen in the CNVA’s organizing model: a mostly decentralized organization of mutually supportive locally- and regionally-based groups — all connected by newsletters, speaking tours, actions, and trainings like this one. Finally, the 1961 “Christmas Week Training” would end with an opportunity to apply some of what the participants had learned — out on the streets of New York. These activists of decades past show us that there is no shortage of opportunities to spin the conversation to the topic of peace and disarmament — and that many of our society’s traditional practices and values contradict our government’s eagerness for war. -- —

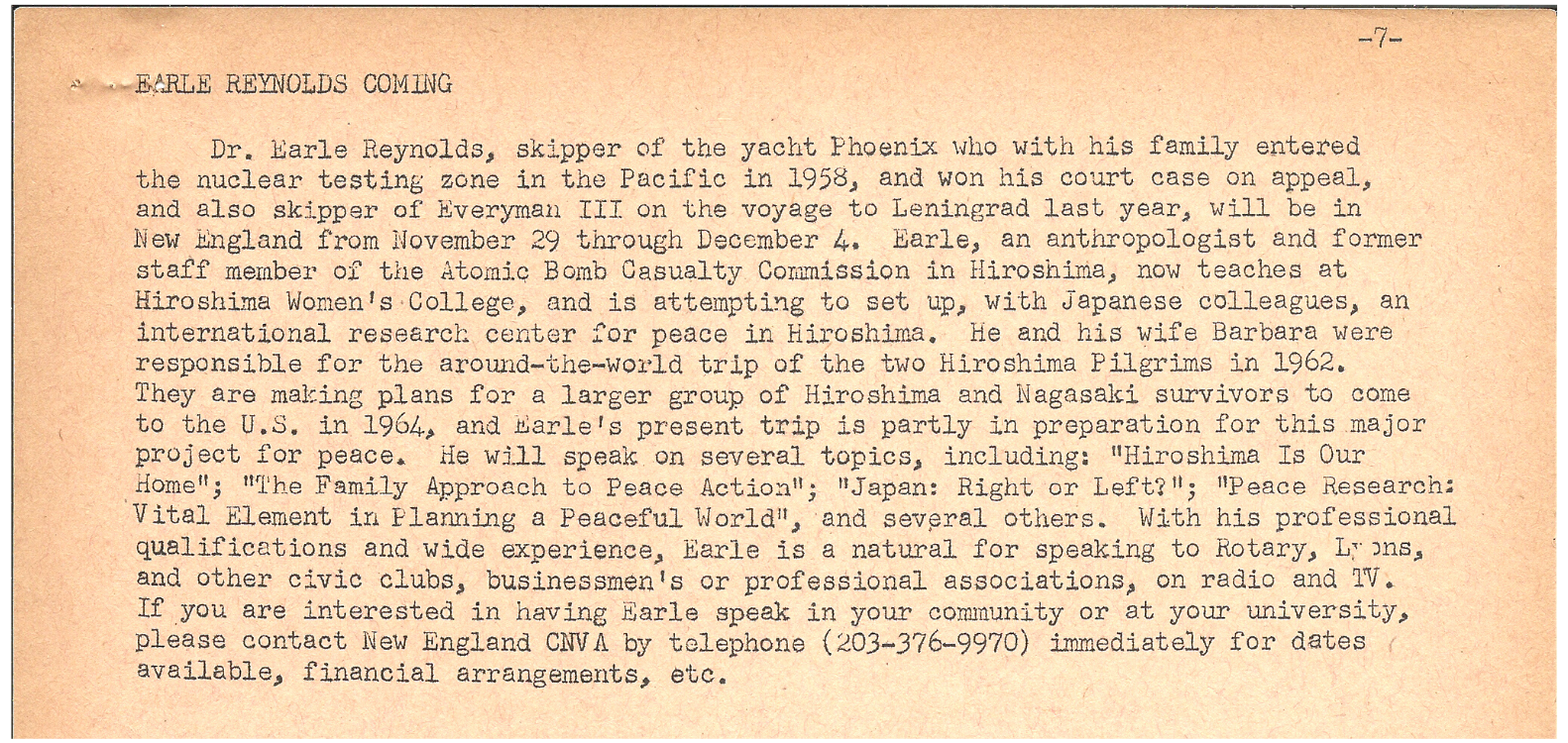

Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “Christmas Week Training and Study Course in Nonviolent Direct Action and Peace Education.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 16 December 1961 (Bulletin #29), pages 3-4. Near the end of the year 1963, the renowned Dr. Earle Reynolds visited New England as part of a speaking tour. Dr. Reynolds had joined the antiwar movement in dramatic fashion and became something of an activist celebrity years earlier in 1958: by sailing with his family (and one Hiroshima citizen) into the US Pacific Proving Grounds in protest of the nuclear weapons his government had been testing there for years. From then on, Earle Reynolds committed himself completely to resisting war and especially nuclear weapons. As a lead researcher for the US Atomic Energy Commission in Hiroshima from 1951 to 1954, Dr. Reynolds became one of the world’s foremost experts on the effects of radiation. Coming to understand the horrors of nuclear weapons better than almost anyone, Dr. Reynolds was so disturbed by what he had found in his research that he abandoned the rest of the study in 1954. Four years later, in the middle of a family sailing trip around the world, the Reynolds family met the crew of the CNVA’s Golden Rule ketch and together decided to carry out the Golden Rule’s mission in its stead: to disrupt the nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific by physically entering the restricted zone. (Read our story on the Reynolds' forbidden voyage here) For the next several years, Dr. Reynolds was prominently involved in a number of high-profile actions against nuclear weapons. He sailed to the Soviet Union twice to protest their participation in the nuclear arms race: the first time again with his family in 1961, the second time as the skipper of the CNVA ship Everyman III in 1962. Back to 1963, Dr. Reynolds would come to share his activist experiences and scientific expertise with some of his most ardent supporters — the premier antiwar group in the 1960s northeast, an organization that came out of the one that sent the Golden Rule to the Pacific in the first place, as well as VPT’s predecessor: the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA). Earle Reynolds, as well as his first wife Barbara, continued antiwar activism for the rest of their lives. Earle would go on to conduct more sail-based antiwar and humanitarian missions, including multiple trips to Vietnam during the American occupation. Barbara’s activist career was arguably even more impressive and deserves its own post at a later date. And while the Golden Rule was not able to complete its first mission, the ketch dutifully served in many more successive actions in the antiwar movement before eventually being scuttled. Years later, Veterans for Peace recovered and restored the ship in order to both preserve its history and continue its function as a protest ship. With a new crew from Veterans for Peace, the restored Golden Rule is currently sailing around the United States to spread its antiwar message. VPT is getting ready to welcome the historic ship when it visits New London in June 2023. See below for the original announcement of Dr. Reynolds’ New England CNVA visit from 1963. And watch this page for updates on events leading up to the Golden Rule’s arrival in New London! -- —

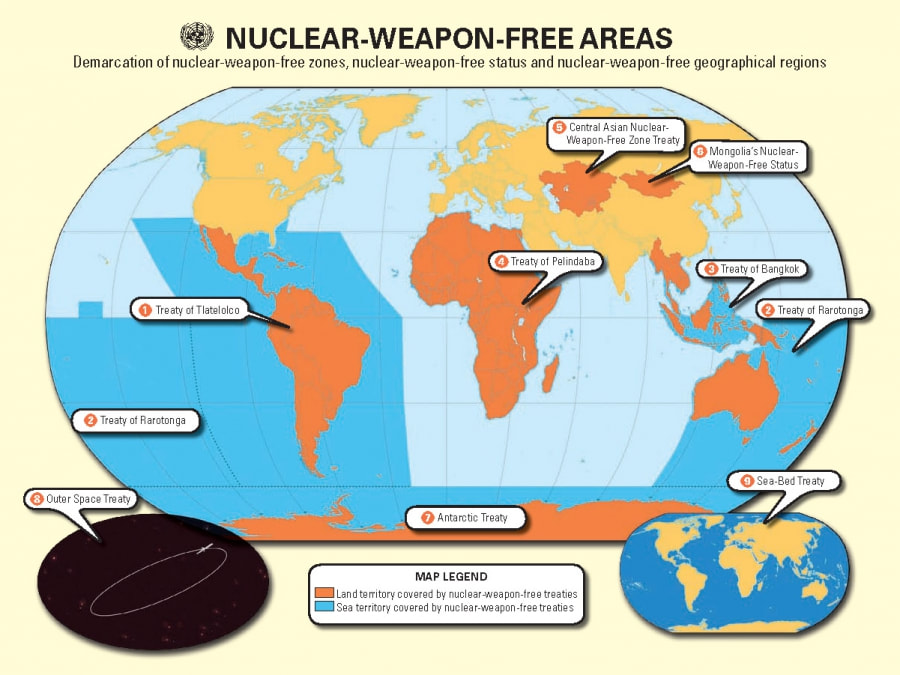

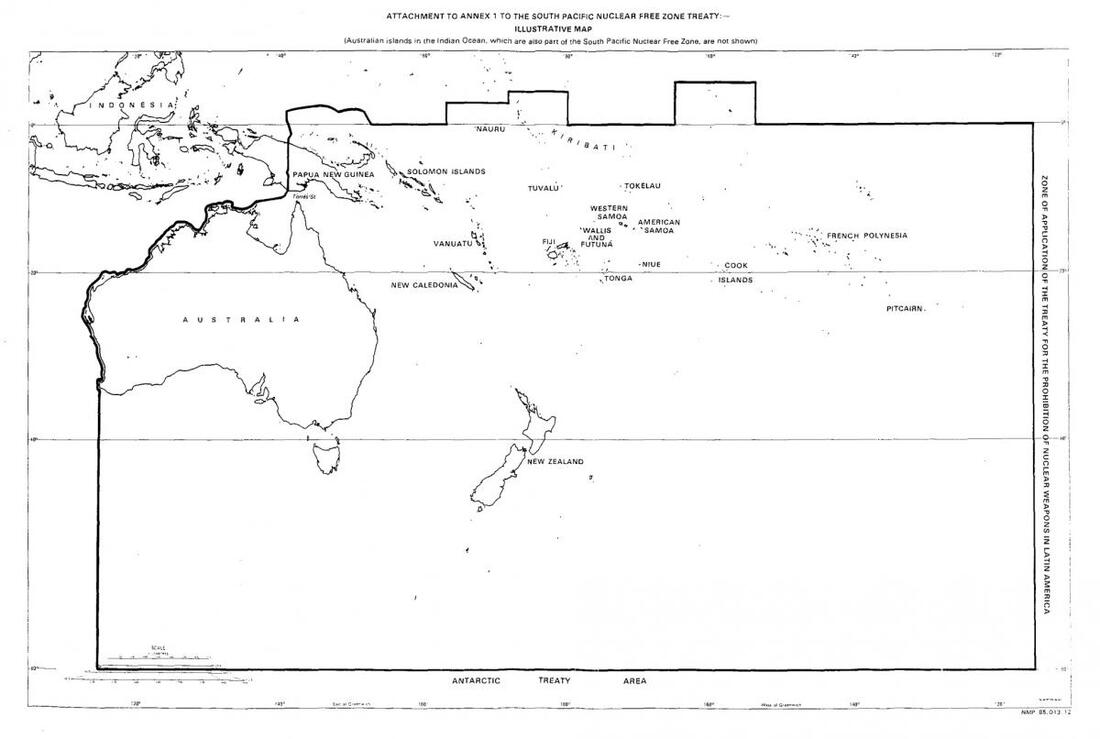

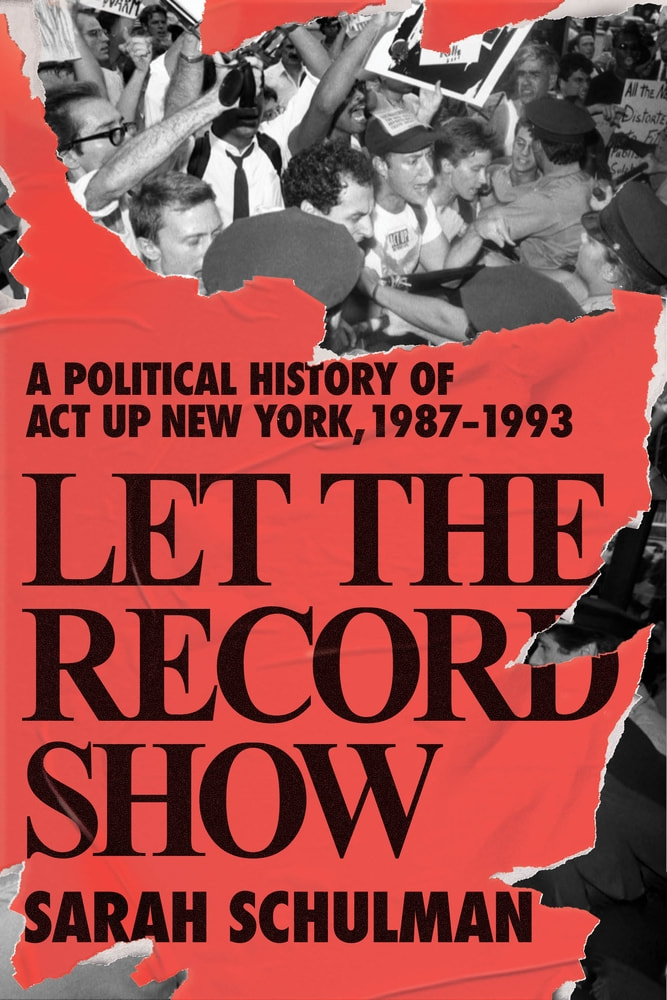

Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “Earle Reynolds Coming.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 28 October 1963 (Bulletin #46), page 7. December 11 is the anniversary of the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty coming into force in 1986 — one of eight international treaties which have banned the development, manufacture, control, possession, testing, stationing or transporting of nuclear weapons across large swaths of the planet. In fact, today, almost all of the sovereign governments in the southern hemisphere have forged regional nuclear-weapon-free zones, with some of these zones reaching up past the equator: all of South America, Central America, and the Caribbean (1968), the Pacific states (1986), and southeast Asia (1997). Central Asia (2009) is well into the northern hemisphere. And all of Africa, the second largest continent on Earth, is a nuclear-weapon-free zone (2009). In addition, Antarctica (1961), outer space (1967), and the seabed (1972) are internationally recognized nuclear-weapon-free zones. These treaties are recognized not just by the party nations, but also by the United Nations as well as the world’s officially acknowledged nuclear weapons states. Most of these treaties are decades old. Sometimes, in the United States, it feels like real change will never come. Opposition to war and promotion of voluntary national disarmament have been some of the most difficult issues for American activists. These demands may seem unrealistic to some, even to other activists. But if we look elsewhere in the world, we find large coalitions of national governments that have done exactly that — some long ago and others quite recently — and spurred on by popular movements of their own citizens. In the words of Nelson Mandela: “It always seems impossible until it’s done.” Below, we share an excerpt from an article on the topic by Lawrence Wittner, history professor at SUNY Albany. In the excerpt, Wittner provides an excellent overview of how determined local activists were able to grow their movements with domestic and international support, and how these movements successfully defied the nuclear weapons states (especially the United States) and convinced their own governments to reject nuclear weapons forever. The link to the full article can be found at the end of this post. -- Although the worldwide campaign against nuclear weapons was in the doldrums during the early 1970s, the antinuclear movement maintained a lively presence in the Pacific, largely in response to nuclear testing in that region. Spurning the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the French government continued atmospheric nuclear testing on Moruroa in the South Pacific, sending deadly radioactive clouds drifting across Pacific island nations. In response, New Zealand activists began defying the French government during 1972 by sailing small vessels into the test zone. Joining the fray, the New Zealand Federation of Labour pledged a strict ban on French goods and the Labour Party took a principled stand against continued nuclear testing, leading to its election victory that November. In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney; scientists issued statements demanding an end to the tests; unions refused to load French ships, service French planes, or carry French mail; and consumers boycotted French products. In Fiji, activists formed an Against Testing on Moruroa organization, which, in 1974, began planning a regional antinuclear conference. Nuclear testing in the Pacific also triggered the establishment of Greenpeace. In 1971, Jim Bohlen and Irving Stowe, two antiwar Americans who had relocated to Vancouver, Canada during the Vietnam War, decided to sail a ship north to Amchitka Island, off Alaska to protest U.S. government plans to explode nuclear weapons there. En route, the crew read of a Cree grandmother's 200-year-old prophecy that there would come a time when all the races of the world would unite as Rainbow Warriors, going forth to end the destruction of the earth. Deeply moved, the crew enlisted in that cause. Although U.S. authorities arrested the crew members as they approached the nuclear test site, thousands of cheering supporters lined the docks in Vancouver upon their return. Bohlen and Stowe embarked on another voyage to Amchitka and, although they failed to reach it before the U.S. government exploded its nuclear bomb, a new movement had been born. In New Zealand, a former Canadian, David McTaggart, convinced Canada's Greenpeace group that he should sail his yacht into France's nuclear testing zone around Moruroa. When he arrived with a crew in June 1972, a French minesweeper, at the order of the French government, rammed and crippled the ship. But McTaggart returned with a new ship and crew the following year.[...] During the early 1980s, as hawkish governments in the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, and elsewhere renewed the Cold War and threatened nuclear annihilation, the movement reached high tide.[...] Australia, like its counterparts elsewhere, experienced a phenomenal growth of nuclear disarmament activism. Antinuclear professional organizations sprang up, and hundreds of small, local antinuclear organizations appeared. Religious groups backed the campaign, as did women's groups, which established peace camps outside U.S. military bases and, in one case, staged a nonviolent invasion of a U.S. base and tore down its gates. Although the newly formed People for Nuclear Disarmament sought to coordinate activities at the state level and the Australian Coalition for Disarmament and Peace at the national one, the movement usually lacked central direction. Even so, the few united events illustrated its unprecedented popularity. On Palm Sunday 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians took to the streets for antinuclear rallies in the nation's biggest cities. Growing year by year, the rallies drew 350,000 participants in 1985. For the most part, the movement focused on abolishing nuclear weapons, halting Australia's uranium mining and exports, removing foreign military bases from Australia's soil, and creating a nuclear-free Pacific. Surveys found that about half of Australians opposed uranium mining and exporting, as well as the visits of U.S. nuclear warships, that 72 percent thought the use of nuclear weapons could never be justified, and that 80 percent favored building a nuclear-free world. In neighboring New Zealand, the movement attained even greater popularity. Older organizations like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament were reinvigorated, while hundreds of newer ones were formed, including a crop of professional groups. Union, church, and Maori organizations joined the antinuclear campaign. In May 1983, 25,000 women participated in an antinuclear rally in Auckland—the largest public gathering of women in New Zealand's history. Continuing their program of resistance, Peace Squadrons sought to prevent visiting U.S. nuclear warships from entering their nation's harbors. In June 1982, when a U.S. cruiser tried to enter Wellington, maritime workers and seamen closed the port for three days through work stoppages, and 15,000 other workers halted labor for two hours to hold protest meetings. In August 1983, 50,000 people turned out for an anti-warship protest in Auckland. Meanwhile, a Nuclear Free Zone Committee pressed to have local governments proclaim their jurisdictions nuclear free. As a result, by 1984, 65 percent of New Zealanders lived in nuclear-free zones. The New Zealand struggle reached a critical point during 1984-85. With the governing National Party (the conservatives) barely able to sustain an effective parliamentary majority against antinuclear resolutions, the prime minister scheduled an election for July 1984. Assuming that a warships ban (and the necessary revision of the Australia-New Zealand-United States alliance) would be unpopular, the Nationalists made the Labour party's antinuclear policy the centerpiece of their campaign. In turn, Labour and two minor parties spoke out vigorously for a nuclear-free New Zealand. On election day, 63 percent of the voters cast their ballots for the three antinuclear parties, catapulting Labour into power. Taking office as prime minister, David Lange announced a four-part program. It included barring nuclear weapons from New Zealand, halting French nuclear testing in the Pacific, blocking nuclear waste dumping in that ocean, and establishing the South Pacific as a nuclear-free zone. When the U.S. government requested entry for a nuclear-capable destroyer, Lange announced in January 1985 that the warship was banned from his country. Although U.S. officials and the opposition Nationalists bitterly condemned this action, it proved enormously popular. Between 1978 and early 1984, polls found that opposition to allowing nuclear armed ships into New Zealand's ports rose from 32 to 57 percent. And once Lange defied the United States, opposition soared to 76 percent. New Zealand had become a nuclear-free nation—and was proud of it. Protest was rising elsewhere in Asia, as well. In the Philippines, the building of a giant nuclear power plant inspired growing opposition, as did U.S. military bases at Subic Bay and Clark Field, which housed nuclear-armed planes and warships. With the government's nominal lifting of martial law in 1981, representatives of church, labor, women's, student, and other groups organized the Nuclear Free Philippines Coalition, dedicated to halting construction of the power plant and closing down U.S. military bases. By early 1983, it claimed the support of 82 organizations. In South Korea, the presence of large numbers of U.S. nuclear weapons and the frightening promises of U.S. officials to employ them in a future war led to a growing public fear of nuclear disaster and protests by church groups. Furthermore, in India, a newly-formed Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy issued numerous public statements by prominent citizens warning against the activities of their nation's "nuclear bomb lobby" and pressed the government to reject nuclear weapons. The antinuclear struggle reached a crescendo in the scattered island nations of the Pacific. Decades of western use of the region for thermonuclear explosions, nuclear missile tests, and nuclear warship ports, topped off by the latest great power nuclear confrontation, led to a surge of resistance among native peoples. In Fiji, church, union, and student organizations established the Fiji Anti-Nuclear Group to work for the creation of a nuclear-free Pacific. In Tahiti, thousands of people marched through the streets protesting French nuclear tests and demanding independence from France. On Kwajalein atoll, some 1,000 Marshall Islanders—reacting to a U.S. government plan to extend its military rights by fifty years—escaped their crowded squalor on Ebeye Island by staging "Operation Homecoming," an illegal occupation of eleven islands they had left years before to accommodate U.S. nuclear missile tests. In Palau, the U.S. government, stymied by that nation's antinuclear constitution, sponsored new referenda to overturn its antinuclear provision. When the third and fourth referenda proved unsuccessful, U.S. officials waged a $500,000 campaign to sway the nation's 7,000 voters in a fifth referendum. But the people of Palau stubbornly voted yet again to keep their islands nuclear free. Deeply resenting their mistreatment by the nuclear powers, delegates to the 1983 Nuclear Free Pacific conference renamed their organization the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement. By 1985, it had 185 constituent organizations. In response to this tidal wave of protest, public policy changed dramatically in the Pacific. In New Zealand, the new Labour government of Prime Minister Lange not only defied Washington by barring nuclear-armed warships, but became a leading proponent of a comprehensive test ban treaty and of a South Pacific nuclear weapons-free zone. In Australia, after the victory of the Labor Party in the 1983 elections, the new prime minister, Bob Hawke, appointed Australia's first minister for disarmament, instructed Australia's representative at the United Nations to support a Nuclear Freeze resolution, withdrew his earlier offer to have Australia test the MX missile, and made his country into a key force in world efforts to secure a comprehensive test ban treaty. Moreover, New Zealand and Australia joined the other eleven nations of the South Pacific in negotiating the Treaty of Rarotonga, designed to prohibit the testing, production, acquisition, or stationing of nuclear weapons in the region. Although nations lacking antinuclear movements, such as China and Pakistan, made progress on their nuclear weapons programs during these years, the Japanese government—beset by waves of protest—proved more cautious, and Japan's "three non-nuclear principles" remained officially enshrined.[...] — Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Lawrence S. Wittner, “Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009. https://apjjf.org/-Lawrence-S.-Wittner/3179/article.html — Further Reading Maharaj, Grace. “The Pacific nuclear legacy belongs to climate change activism” Griffith University: Asian Insights, 13 August 2020. https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiainsights/the-pacific-nuclear-legacy-belongs-to-climate-change-activism/ “Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs, accessed 7 December 2022. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/nwfz/ In observance of World AIDS Day, here we have two excerpts about Jamie Bauer: a member of ACT UP who directly helped shape the organization. Jamie brought the protest tactic of nonviolent civil disobedience to ACT UP, training members who went on to train even more — rippling out to an enormous scale. According to many within the movement, it was nonviolent civil disobedience which largely made ACT UP so successful. Jamie Bauer had been influenced by Barbara Deming, a feminist lesbian activist and writer who had been involved in the antiwar group the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA), which founded the original Voluntown Peace Trust. Jamie was also active with the Women’s Pentagon Action, which was supported by the War Resisters League (WRL). Because of that connection, Jamie knew WRL staff member David McReynolds, and the two ran a training that influenced ACT UP to use nonviolent tactics. David McReynolds also worked with Barbara Deming in both CNVA and WRL (learn more from Martin Duberman’s book A Saving Remnant: the Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds). By the time Jamie Bauer was getting involved with ACT UP, the CNVA had merged into WRL. The closer one looks, the more direct connections one can see between ACT UP, the antiwar movement, the civil rights movement, and many more of the time. In 2020, T: The New York Times Style Magazine interviewed 12 veteran activists of ACT UP to tell their experiences in the organization in their own words. Jamie Bauer was one of the members interviewed, and we have shared their words below. In 2021, a book was published about this period: Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman. Chapter 16 of the book is about the role of civil disobedience in ACT UP, and Jamie Bauer is a central figure throughout. Below, we share excerpts from the beginning of the chapter (find the source link at the end of this post to find your own copy and read the whole story for yourself). --

From “12 People on Joining ACT UP: ‘I Went to That First Meeting and Never Left’” in T: The New York Times Style Magazine JAMIE BAUER, 61 Joined in 1987 In 1981, I became active in the Women’s Pentagon Action, which is a feminist, anti-militarist group with connections to the War Resisters League (WRL), one of the oldest pacifist organizations in the United States. I was trained in nonviolent civil disobedience: We would discuss a demonstration and really walk through the safety of it to make sure that we weren’t doing anything to intentionally hurt people. When ACT UP started in 1987, some of the organizers of the first meeting reached out to the WRL. David McReynolds, a longtime member, and I dispatched WRL members who understood nonviolent civil disobedience — and that included the two of us, both queer — to go to the ACT UP meeting and do a brief training. After that, I just stuck with it. As a pacifist, for me, it was always about acknowledging your anger and channeling it into something productive — and, of course, with people dying, there was so much anger. Although ACT UP did not take a vow of nonviolence, we had a series of principles that were built upon that; we had very clearly drawn lines. For me, the biggest struggle was working with people to make sure that we didn’t overstep those boundaries, that we didn’t turn into the Weathermen [the ’60s and ’70s-era radical faction of the left-wing Students for a Democratic Society], that we didn’t bomb buildings — which, in a time of desperation, when you’re watching all your friends die, would have been an easy direction for us to go in. -- From Chapter 16: The Culture and Subculture of Civil Disobedience in Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman The most influential cohering experience in values inside ACT UP that almost everyone shared was civil disobedience training, and thousands of people experienced it together. Although based in an applied practice with tips and guidelines, all of the instructions were rooted in a very articulate and deep ethical belief system about community. The trainers became a moral center of this culture, profoundly influential on the movement as a whole, and specifically consequential on the individuals who shared this preparation and subsequent experience of nonviolent defiance. JAMIE BAUER Jamie Bauer grew up in Stuyvesant Town, in Manhattan. Their father was a salesman, and their mother was a homemaker. After Hunter High School they went to MIT to study civil engineering, architecture, and urban planning, and earned a master’s in transportation, which had a one-in-eight women-to-men ratio. Jamie found the program to be not very intellectual. “Rigorous, but not very interesting.” Although there was a small gay student union at the school, it was all men. On the other hand, MIT was in Boston, which had a huge lesbian community. And so Jamie came out pretty quickly and start making some connections into the mixed gay movement and into the lesbian movement, the two of which were still somewhat separate at that point. In 1981, they returned to New York to work for the MTA, eventually as director of subway schedules. About two decades after their time in ACT UP, Jamie started to live as nonbinary. In the early 1980s, Jamie had heard a lot about the Women’s Pentagon Action, a mobilization to create a large women’s peace action directly confronting the Pentagon. They went to a couple of meetings and got hooked, “because these women were so interesting and so smart and creative, and knew so much. And I just thought—Well I’m just going to sit here and hang out and absorb this.” Jamie worked with Grace Paley, Vera Williams, Eva Kollisch, Donna Gould, Sharon Kleinbaum, Toni Fitzpatrick, Laura Flanders, Harriet Hirschorn, and other women peace activists. The group came together to make the connections between war, the patriarchy, women’s oppression, the military–industrial complex. It was also an antinationalism group. They did not believe in borders, flags, or patriotism, and believed that women bonding together with other women could save the world. And at that time, 60 to 75 percent of the group were lesbians, but that fact was not acknowledged. “It wasn’t part of the dogma of the group. We were women—which I found a little hard to stomach, because it was so clear that so many [of the] women were lesbians anyway, but they didn’t want it to be a lesbian group.” Jamie learned a lot about organizing, dealing with the police, insisting on the right to take space, and just everything about doing politics on the street.[...] Influenced by the writings of Barbara Deming, Jamie picked up the concept that people have a right to free speech and freedom of assembly and should not have to ask permission for it. And if the state wanted to arrest us for it, that was their business, but the people were not going to ask the state’s permission. So it was nonviolent civil disobedience rooted in an insistence on people protecting their rights by using them, and not letting the government take those rights. When they first came to ACT UP, Jamie found it all very exciting. People were so charged up and just wanted to demonstrate, demonstrate, demonstrate. ACT UP would schedule five demonstrations in a week, and then the members would go to all of them. But Jamie found that they didn’t know anything about demonstrating. For example, at the first Wall Street demo, ACT UP gave the police a list of the seventeen people who were going to be arrested, and each person who was going to be arrested wore an armband so that the police wouldn’t accidentally take the wrong person. Jamie felt that this was overly orchestrated and made it impossible for anybody else to try to jump in. Jamie called this “Celebrity CD [civil disobedience]. They didn’t want three hundred people, at that point, necessarily doing CD. They wanted a couple of name people, with recognition so that would be what would be in the press.” Jamie understood that ACT UP was trying to figure out how to use its anger, because it was a group with a tremendous amount of rage and anger at the system. Although New York City was the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic, the federal decision-makers were in Washington. It was very frustrating to go out into the streets of New York and demonstrate, because they were demonstrating against buildings that people in power weren’t necessarily in. For Jamie, civil disobedience is an American tactic that people understand, in some ways. But Jamie had a particular commitment to a concept of safety. There were people who didn’t understand issues of public safety, personal safety, the safety of the community, or taking responsibility for one’s actions. Jamie and the other trainers really began to talk about civil disobedience as a safe tactic for making a stronger, direct, personal statement, and as a way of getting media attention. They tried to get everybody in the group trained for civil disobedience, because no one always knows when it’s going to happen, or when they’re going to want to do it. When dealing with the police, no organizers can guarantee people’s safety; there are a lot of things that can make it physically safer than just haphazardly running out into the street.[...] — Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. Macmillan: 2021. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374185138/lettherecordshow Turner, Kyle. “12 People on Joining ACT UP: ‘I Went to That First Meeting and Never Left’”. T: The New York Times Style Magazine, published 13 April 2020 (updated 17 April 2020). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/t-magazine/act-up-members.html — Further Reading Duberman, Martin. A Saving Remnant: the Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds. The New Press: 2012. https://thenewpress.com/books/saving-remnant |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed