|

Almost two months ago, we recounted the story of the first modern protest ship, the Golden Rule, which in 1958 the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) sponsored to sail from Hawai’i into the sea around the Marshall Islands (read about here: https://www.facebook.com/VoluntownPeaceTrust/posts/1970864523063873). The goal of the four-crew vessel was to disrupt the ecologically-devastating and belligerent US nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Ocean. Although the Golden Rule was prevented from achieving its goal, the peace vessel’s crew inspired the crew of another ship, the Phoenix of Hiroshima, to attempt the mission. The “Forbidden Voyage,” as the Phoenix’s captain Earle Reynolds would call it, changed his life and the lives of the other four on his yacht, made history as the first civilian vessel to ever disrupt a nuclear weapons test, and possibly influenced the US to accept the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

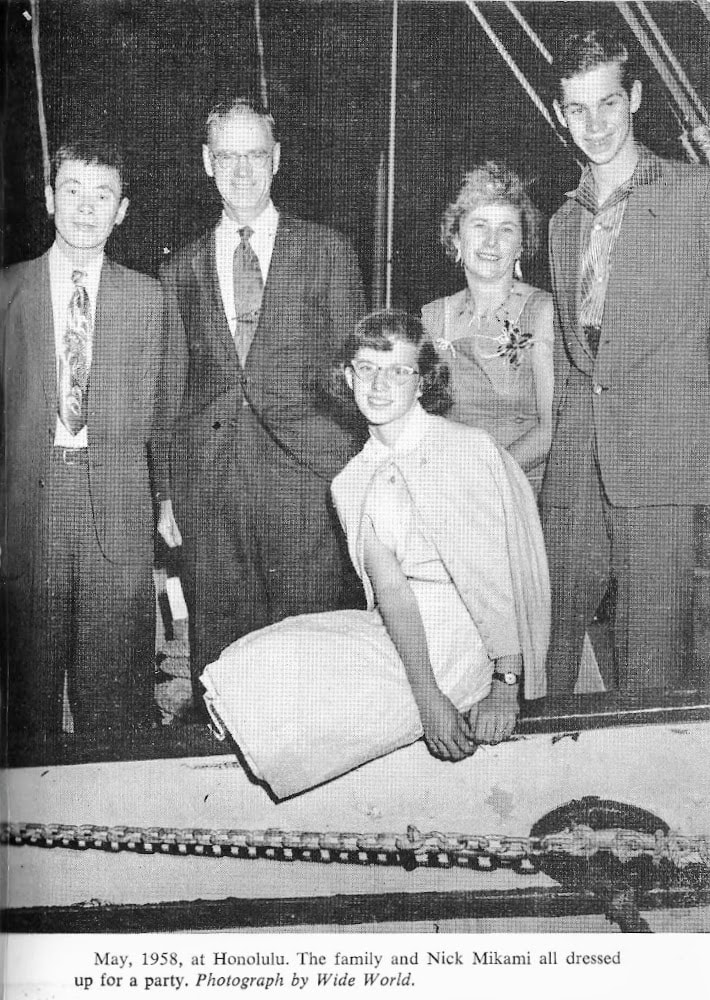

Anthropologist Earle Reynolds had not planned to become a peace activist: not when he left Antioch University to work for the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in Japan in 1951, nor after studying the effects of radiation on Japanese children for three years, becoming one of the world’s experts on health and radiation. Instead, Earle followed his dream of having a yacht built in which to travel the world with his family. In 1954, a native Hiroshima shipbuilder Mr. Yotsuda finished the 50 ft two-sail ketch to Earle’s specifications. Inspired by the mythical bird that rises from its own ashes, shared by both Western and Eastern traditions, and also by the fact that the East Asian variety symbolizes peace, they christened the ship the Phoenix of Hiroshima. Earle Reynolds completed the first part of his report to the AEC and, on May 5, 1954, he, his family, and three Japanese crewmen set sail. Earle, his wife Barbara, son Ted (16), daughter Jessica (10), and three young Japanese yachtsmen from Hiroshima, Niichi ("Nick") Mikami, Motosada ("Moto") Fushima and Mitsugi ("Mickey") Suemitsu first sailed to Hawai’i before looping down to the islands of the South Pacific, New Zealand, Australia, and Indonesia. They continued on west, stopping in South Africa rather than attempt the northern route during the Suez Crisis, stopping in Brazil, doing a tour of the east coast of the United States, visiting the West Indies, and crossing through the Panama Canal. There, Motosada and Mitsugi flew home. By that point, about four years into their journey, the Reynolds family had become well-experienced sailors themselves. When the Phoenix finally returned to Hawai’i, they found the Islands abuzz about the Quaker pacifists of the Golden Rule — the day before the Phoenix had arrived, the crew of the Golden Rule had made their first attempt. Earle, upon first hearing about the attempted action, thought that they sounded “a bit like crackpots” but also that “it’s about time somebody did something about those tests.” But after Barbara urged him to attend the Golden Rule crew’s trial, Earle quickly became fascinated by these men and tried to learn everything he could about their case. Ted, now 20 years old, also researched what he could about the legality of the injunction the US government had imposed while the Golden Rule had been en route from San Pedro to Honolulu. Meanwhile, Earle investigated his old employer, the AEC, discovering that the government agency had “been playing false with the American public” with regards to the extreme dangers of radiation. Father and son determined that the injunction had no legal precedent, actually contradicted international maritime law, and could not hold up in “an honest court.” Barbara, for her part, was almost immediately moved by the men’s moral conviction. In a newsletter to their hundreds of friends and fans, they condemned the AEC and announced their support for the Golden Rule. Only intending to stay for a couple weeks in Hawai’i before heading back to Hiroshima, the Reynolds family quickly realized that the nuclear tests blocked their route home too, and the bureaucratic process to pass through the zone legally seemed interminable. Meanwhile, the Golden Rule crew continued to impress the Reynolds family. On the evening of June 3, the day before the Golden Rule made its second attempt, its crew Albert Bigelow, Jim Peck, George Willoughby, and Orion Sherwood had dinner with the Reynolds family and Niichi, during which Earle expressed his desire to help the Golden Rule somehow. A few days after the crew of the Golden Rule were stopped and jailed for the second time, the Phoenix crew debated whether to take on the Golden Rule’s mission in their stead; they decided to sail as far as they could toward Hiroshima and to make the ultimate decision at sea, as they neared the restricted zone. Earle himself did not like to break rules and was also not eager to end his professional career — he knew that the AEC would never accept him back, and that he would likely be blacklisted in academia. But the coincidences were too great not to consider: the Phoenix was built in Hiroshima, the first victim of a nuclear attack; Niichi was a Hiroshima citizen whose family members had suffered and died as a result of the bombing, and was wholly supportive of the endeavor; Earle was one of the world’s foremost experts on the effects of radiation, and was personally concerned about it; they were intending to head back to Japan through that route anyway; and finally, as Barbara impressed on Earle, they were there at the exact time and place with the exact means to help. The Golden Rule crew gave the Phoenix crew their supplies. Earle and Barbara considered leaving Jessica, now 14 years old, in Honolulu and sending for her grandmother to take care of her, but Jessica fiercely refused to be left behind, arguing, “Remember, it’s my world too, and I have a right to fight for it just as much as you have.” On June 11, the Phoenix left for the restricted zone, but unlike the Golden Rule, no one tried to stop the Phoenix at first. After sailing for 20 days, as the Phoenix approached the edge of the restricted zone, the decision was finally made. Around noon on July 1, 1958, Earle announced by radio that they were crossing into the zone “as a protest against nuclear testing,” and at around 8:00pm that evening, the Phoenix did just that. The next day, Earle was arrested. Earle Reynolds was convicted of trespassing in the restricted zone, but he appealed and eventually had the conviction overturned. As he and his son Ted had suspected, the injunction had been illegal after all. Ultimately returning to Japan, the Reynolds family were hailed as heroes and the Phoenix as a national shrine. Niichi Mikami was praised as the first Japanese yachtsman to circumnavigate the globe, and moreover as an exemplary Hiroshima citizen in crossing into the restricted zone with the Reynolds family. Due to the experience, both Earle and Barbara became peace activists and continued to do actions. In 1961, the family sailed to Nakhodka, USSR with hundreds of letters appealing for peace from Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors, but were turned away by the Soviet Coast Guard. In 1962, Earle sailed to the Soviet Union again, this time as the captain of another CNVA vessel, Everyman III. Meanwhile, Barbara traveled around the world with two hibakusha (people affected by nuclear explosion) as Peace Pilgrims, urging world leaders to ban nuclear weapons. After their divorce in 1964, Earle and Barbara separately continued to work for peace, with Earle attempting “friendship and reconciliation” voyages into China in the late 1960s, and Barbara founding the World Friendship Center in Hiroshima 1965 to share the stories of hibakusha to foreign visitors. Years later, Barbara would assist Cambodian refugees fleeing Pol Pot. Their daughter Jessica went on to write many articles and three books about their experiences as peace activists on the high seas over the years, and their granddaughter Naomi Reynolds has been involved in raising and restoring the original Phoenix of Hiroshima. Regardless of the future for the Phoenix, the legacy of the Reynolds’ initial “Forbidden Voyage” reached far beyond the restricted areas around the Marshall Islands and provides inspiration for us today. — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “1951-1954: Origin of Phoenix.” Phoenix of Hiroshima Project. (Accessed 28 July 2021). https://phoenixofhiroshima.wordpress.com/our-history/building-the-boat/ “1954-1958: The Reynolds’ Family Voyage.” Phoenix of Hiroshima Project. (Accessed 28 July 2021). https://phoenixofhiroshima.wordpress.com/our-history/1951-1958-the-reynolds-family-voyage/ “1958-1961: Nuclear Protests.” Phoenix of Hiroshima Project. (Accessed 28 July 2021). https://phoenixofhiroshima.wordpress.com/our-history/pleasure-yacht/ “Friends Journal 1958 coverage of the Golden Rule.” Friends Journal. 31 July 2013 (accessed 28 July 2021). https://www.friendsjournal.org/golden-rule-1958/ Reynolds, Earle. The Forbidden Voyage. David McKay Company, Inc., 1961. “The Golden Rule and Phoenix voyages in protest of U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands, 1958.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. (Accessed 28 July 2021). https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/golden-rule-and-phoenix-voyages-protest-us-nuclear-testing-marshall-islands-1958 Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed