|

Native American rights and history have been a concern for the Peace Trust for decades; the 1990s campaign to remove the John Mason statue in downtown Mystic is a prime example (see the story here). But it was only a few years ago that we learned that part of our organization’s name — the “Voluntown” of the Voluntown Peace Trust — was a reference to lands conquered from local Native communities and granted to colonial volunteer soldiers in the so-called King Philip’s War (aka Metacom’s War).

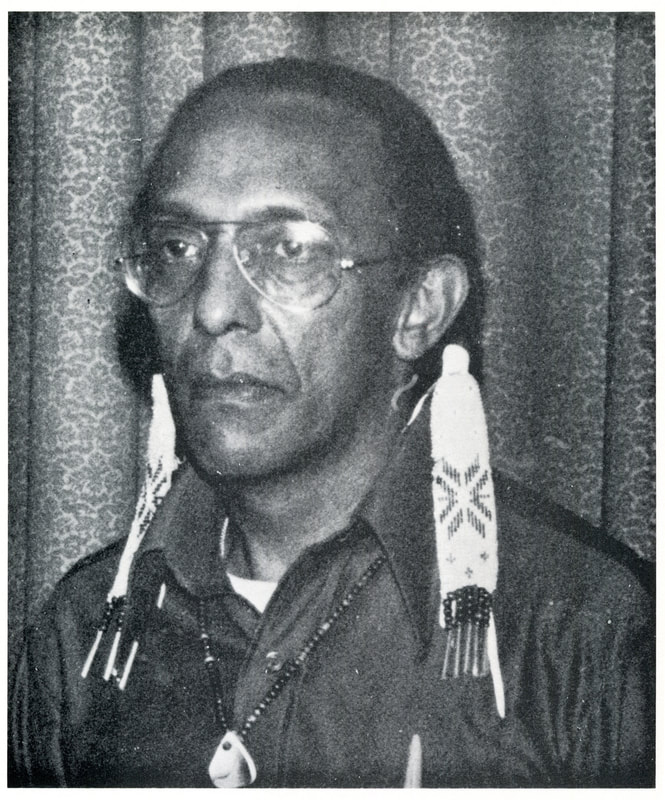

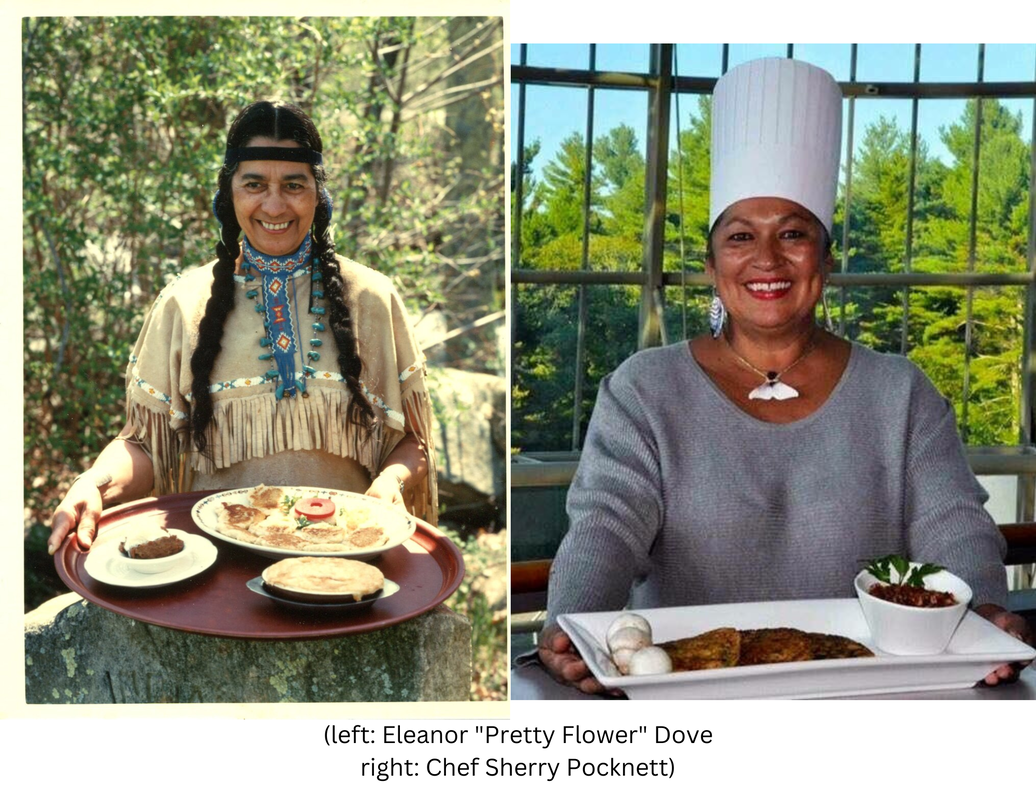

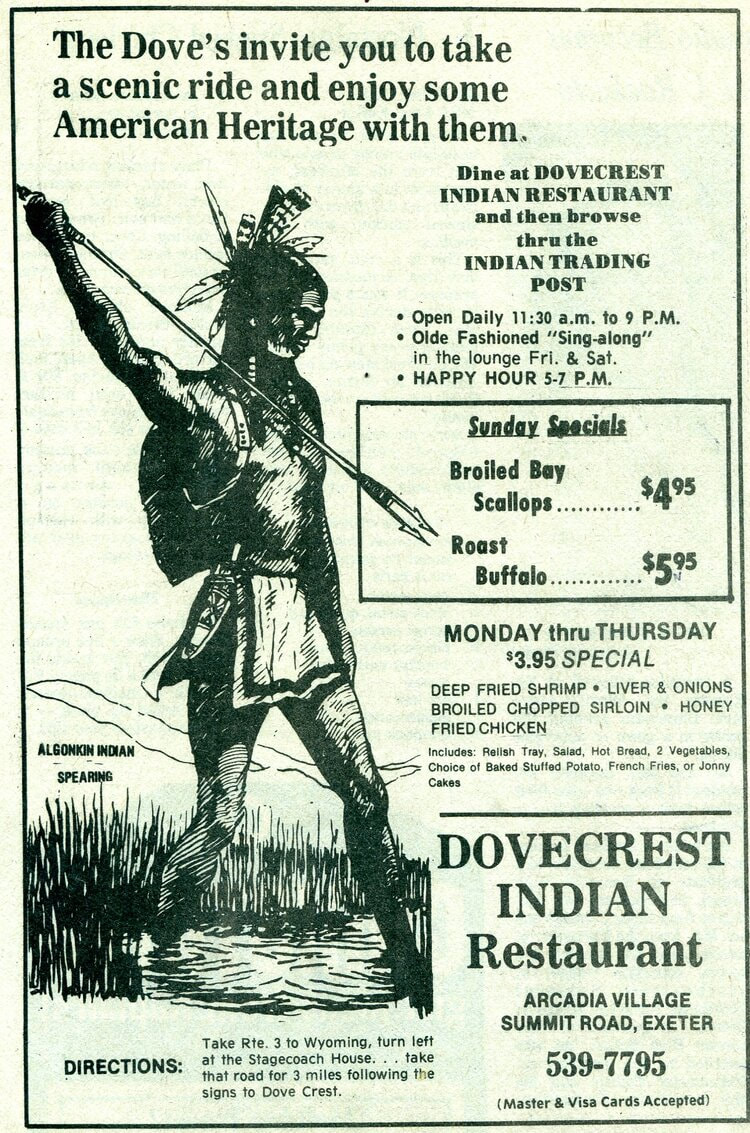

While the war was technically started by a coalition of Native groups led by Wampanoag leader Metacom, it was provoked by years of English aggressive expansion, assertions of dominance, and violations of treaties. In the end, the English colonists turned the conflict into a war of extermination, killing so many Wampanoag and Narragansett peoples that the two formerly powerful nations have not fully recovered to this day. The following is an account of Wampanoag history by Wamsutta (aka Frank James), Wampanoag leader in 1970. Shortly after the Commonwealth of Massachusetts denied his speech and returned to him a whitewashed version, Wamsutta founded the United American Indians of New England and declared Thanksgiving day a National Day of Mourning for Native Americans. This speech became a foundational text for the group, and remains a powerful retelling of the regional history through the Wampanoag perspective. As part of our efforts to learn more about local Native history, spread that historical understanding, and uplift Native voices, we again present “The Suppressed Speech of Wamsutta.” -- “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG” To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970 ABOUT THE DOCUMENT: Three hundred fifty years after the Pilgrims began their invasion of the land of the Wampanoag, their "American" descendants planned an anniversary celebration. Still clinging to the white schoolbook myth of friendly relations between their forefathers and the Wampanoag, the anniversary planners thought it would be nice to have an Indian make an appreciative and complimentary speech at their state dinner. Frank James was asked to speak at the celebration. He accepted. The planners, however, asked to see his speech in advance of the occasion, and it turned out that Frank James' views — based on history rather than mythology — were not what the Pilgrims' descendants wanted to hear. Frank James refused to deliver a speech written by a public relations person. Frank James did not speak at the anniversary celebration. If he had spoken, this is what he would have said: I speak to you as a man -- a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction ("You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!"). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so. It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt's Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people. What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called "savages." Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other "witch." And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the "savage" and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again. The white man used the Indian's nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman -- but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we Indians have been termed "low man on the totem pole." Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons. What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as "civilized" people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags'] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty. History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood. The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his "savageness" has boomeranged and isn't a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian's temperament! High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians! Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently. Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting We're standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us. We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail. You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian. There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We're being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours. Wamsutta September 10, 1970 — Take Action See how you can support the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative: http://www.narragansettfoodsovereignty.org/ Donate to the Sly Fox Den project here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/sly-fox-den-restaurant-and-bar Join our mailing list for announcements of upcoming events on Native history: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source James, Wamsutta (Frank B.). “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG.” United American Indians of New England. http://www.uaine.org/suppressed_speech.htm — Further Resources Here is a podcast episode for all ages about Wampanoag and Narragansett thanksgiving traditions featuring Loren M. Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum: “Giving Thanks!” Time For Lunch podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/giving-thanks/id1504928110?i=1000499993371 From 1963 to 1984, there was a Native American restaurant called Dovecrest in Exeter, Rhode Island. The place was founded by Eleanor (Pretty Flower, 1918-2019) and Ferris Babcock Dove (Chief Roaring Bull, 1915-1983), both members of the Narragansett-Niantic Tribal Nation. The eatery originally served “standard steakhouse fare,” but eventually some patrons started asking to try the traditional Indigenous food the family ate in the back. Soon, Indigenous cuisine was featured on the Dovecrest menu. But to call Dovecrest just a restaurant would be inaccurate — it was so much more than that. It was a meeting place and cultural center for many Narragansett-Niantic people in the area. It was an educational facility to spread knowledge of Narragansett-Niantic traditions, cultural practices, and of course, cuisine. And, starting in the late 1960s, Dovecrest became the home of Red Wing (Mary E. Congdon, 1896-1897), a very prominent storyteller and keeper of cultural knowledge for the Narragansett-Niantic and Wampanoag Tribes. When Red Wing moved in, she brought with her the contents of the first Tomaquag Museum, and reestablished the museum at Dovecrest. Today, the restaurant is no more, but the Tomaquag Museum is still there, at the old Dovecrest location. Soon, southeastern Connecticut will have a local Indigenous restaurant / community space / educational facility, too. Chef Sherry Pocknett, who was featured in a Time Magazine article earlier this week (link in the sources below), is a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Nation who is currently raising funds for a new facility on the Poquetanuck Bay in Preston, Connecticut. It will be called Sly Fox Den, and the full plan involves not just a Native cuisine restaurant and bar, but also an “Indigenous Native American Living Museum and Oyster Farm” which will include traditional Wampanoag buildings and gardens, an outdoor cooking area, an oyster farm, and live demonstrations of traditional Wampanoag tradecrafts like canoe-making. While funds are being raised for the primary Connecticut site, Chef Sherry Pocknett has opened another restaurant in Charlestown, Rhode Island — Sly Fox Den Too. Perhaps remembering the Narragansett Dovecrest Restaurant of decades past, the local Narragansett community around Charlestown graciously welcomed Chef Sherry Pocknett and her Wampanoag family when she opened the restaurant in the summer of 2021. Certainly, there is a history of immeasurable injustice committed by English colonists (and later “Americans”) to the Native peoples of this country, and it is vital that that history be shared, discussed, and addressed. But it is just as important to tell and celebrate the stories of Native resilience and accomplishments — from times past up to the present. While we eagerly wait for the opening of the primary Sly Fox Den in Connecticut, we share the following excerpt about their spiritual predecessor: Dovecrest Restaurant. To read the whole piece, find the original at the Tomaquag Museum’s blog Belongings. Check the source below the excerpt for the link to the full blog post, which includes additional details on the Dove family, Red Wing, the thanksgiving celebrations at Dovecrest, and more. On the Belongings blog page, you will also find four special Indigenous recipes! —

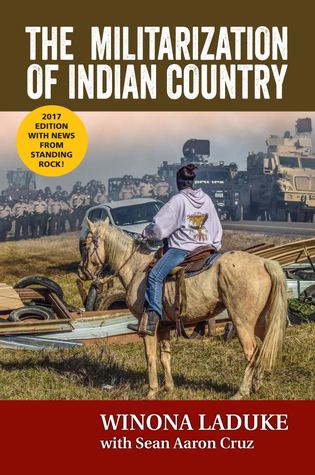

…Initially, when the Doves had opened Dovecrest Restaurant the menu offered “standard steakhouse fare,” which was typically considered main dishes such as beef steaks, pork chops chicken and seafood with sides of vegetables and hearty soups, stews and chowders- your typical Yankee style meat and potatoes type restaurant. (This was very much the backbone of the Dovecrest Restaurant for its entire existence.) It wasn’t until a few years after Dovecrest was in operation that patrons of the restaurant noticed that the Doves were preparing different meals for their children in the room behind the kitchen. These meals comprised of wild meats, or “game” meats. Soon, customers were asking that if instead of ordering the standard steakhouse fare, they were able to order dishes such as venison stew and creamed dried cod. Venison was of course an important staple for the Indigenous people throughout time on both the North and South American continents. Venison was essential to both survival and culture as the white tailed deer provided not only food, but clothing, adornments and tools. Ferris, in his own words, “When I was growing up in Charlestown, we depended on food like venison. We would have feasts of venison steaks, oysters we pulled from the bay, Johnnycakes and potatoes. This was 1930, and only the poor people were eating that stuff. Now it’s a delicacy. Isn’t it funny how things change?” And things did change. Slowly, but surely the Doves began incorporating wild game and other traditional Indigenous recipes, some that Eleanor had learned from her father, Joseph Spears, Sr. (who had also been a chef at the University Club in Providence) into the menu. These wild games were then appeared on for special occasions or whenever wild game or shellfish happened to be available and/or in season. Eleanor said she tried to always keep one game dish on the menu, but it was often difficult to have a steady stock on hand. Many of the wild game was procured locally, from friends and neighbors who hunted, but for other types of game, such as bison they had to rely on private, out of state distributors such as ranch in Western Massachusetts or Iron Gate Products in Manhattan. As the specialty wild game dishes began appearing on the menu, word traveled fast and Dovecrest started to become well known as a restaurant that was not only owned and operated by Indigenous people-at that time the only such establishment east of the Mississippi River-but Indigenous people who were also serving traditional Indigenous foods in this small, out of the way place in rural Exeter. One of the dishes which became a specialty at Dovecrest was a “briny fresh clam chowder” which were of course locally sourced from Narragansett Bay and other locations in Rhode Island and were shucked by Ferris every Friday and according to Eleanor “does it faster than anyone I’ve ever seen.” In addition to the venison stew, creamed dried cod and briny; or Rhode Island style clam chowder, Dovecrest entrees on the menu could include bison steak and pie, quahog pie, venison steak and pie, rabbit stew, squirrel pie, racoon pie, bear, elk, succotash, Indian pudding-and what they became most famous for, Johnnycakes. Johnnycakes, or “Journey cakes” as they were known during the contact (Colonial) period, were a traditional staple of Indigenous people throughout North America and the Caribbean before the invasion of Europeans and was quickly adopted by European colonists and anglicized into what we know now as Johnnycakes. Usually (but not always) they are made out of ground white flint maize, water, milk and butter, salted with a little sugar and cooked on a griddle until deep golden brown, Johnnycakes then became a staple of European colonial life and like many of the plants and animals in the Americas slowly had their Indigenous roots erased through time. Johnnycakes were served plain, as is, or with additional local, seasonal ingredients such as maple syrup, blueberries and cranberries. Over the years as their reputation grew, Dovecrest Restaurant was recognized in many ‘Best of” guides, winning rave reviews for their Johnnycakes as often the best in the state (and even some said New England) appearing in a New York Times article ‘Cuisine as American as Raccoon Pie’ in December 9, 1981 and even winning a 1982 Ocean Spray Cranberry Salute to American Food Award in Pittsburgh in addition to a USA Today article, ‘On The Menu Succotash and Venison.’ All of the awards and accolades were hard earned and well deserved for Dovecrest Restaurant, especially the Dove matriarch Eleanor, who was the primary chef and ran the kitchen. According to Ferris, “she’s the cook and I’m the waiter.” In addition to Ferris’ clam shucking, bartending and wait duties, Dovecrest Restaurant and Trading Post was a family operation and relied on the help of close family members such as their children, Mark, Paulla, Dawn and Lori and later granddaughters Elisabeth Dove (Manning) and Lorén Wilson (Spears) as well as Eleanor’s father Joseph Spears, Jr. and Ferris’ mother Mimi Babcock Dove as well as other extended family members and local tribal members… — Take Action See how you can support the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative: http://www.narragansettfoodsovereignty.org/ Donate to the Sly Fox Den project here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/sly-fox-den-restaurant-and-bar — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “From the Archives: Dovecrest Restaurant & Thanksgiving.” Tomaquag Museum. 26 November 2020 [Accessed 17 November 2021]. https://www.tomaquagmuseum.org/belongingsblog/2020/11/2/dovecrest-restaurant-and-thanksgiving Burns-Fusaro, Nancy. “Indigenously Delicious: Sly Fox Den Too opens in Charlestown.” The Westerly Sun, 21 July 2021. https://www.thewesterlysun.com/news/charlestown/indigenously-delicious-sly-fox-den-too-opens-in-charlestown/article_5bd5e3be-e4be-11eb-8294-c7f7dce648e1.html “Our Mission.” Sly Fox Den Restaurant. https://slyfoxdenrestaurant.com/our-mission Waxman, Olivia B. “Her Tribe Fed the Pilgrims. Here’s What She Wants You to Know About Indigenous Food.” Time Magazine, 15 November 2022. https://time.com/6233957/indigenous-chef-thanksgiving-pilgrims/ — Further Resources Here is a podcast episode for all ages about Wampanoag and Narragansett thanksgiving traditions featuring Loren M. Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum: “Giving Thanks!” Time For Lunch podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/giving-thanks/id1504928110?i=1000499993371 For Veterans Day, we again share excerpts from Winona LaDuke’s 2013 book The Militarization of Indian Country. We want to help shine light on the connections between the US military and many issues (past and current) that affect Native communities in the United States. The relationship between the US military and Native Americans is complex, but also clearly unequal and abusive. From her research, LaDuke tells story after story of the US military’s rapacious exploitation and consistent denigration of Native individuals, communities, and lands — a colonialist project that continues to this day. Little has changed in Native affairs since last November, and so we are posting these excerpts again this year. Winona LaDuke is a Native American Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) activist-economist who is known for her involvement in many large Native projects: the White Earth Land Recovery Project, which reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people (including Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm); Honor the Earth, a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues; and most recently, the Line 3 pipeline protests that seek to prevent enormous ecological disasters in Native lands. Following the whirlwind of political activism that brought down statues of slave owners, Columbus, and other colonizers in the last few years, many of these campaigns that did not resolve quickly have either become mired in bureaucratic purgatory or sputtered out altogether — the statue of John Mason, now-infamous leader of the Mystic Massacre, still stands at the Capitol in Hartford. Line 3 construction continues, as does Native resistance to it. The exploitation of Native peoples, present and past, goes on unabated. As LaDuke recently put it in an article for InForum: “Stop the Indian wars, and make new history.” (See below for the excerpts from The Militarization of Indian Country) — [...]

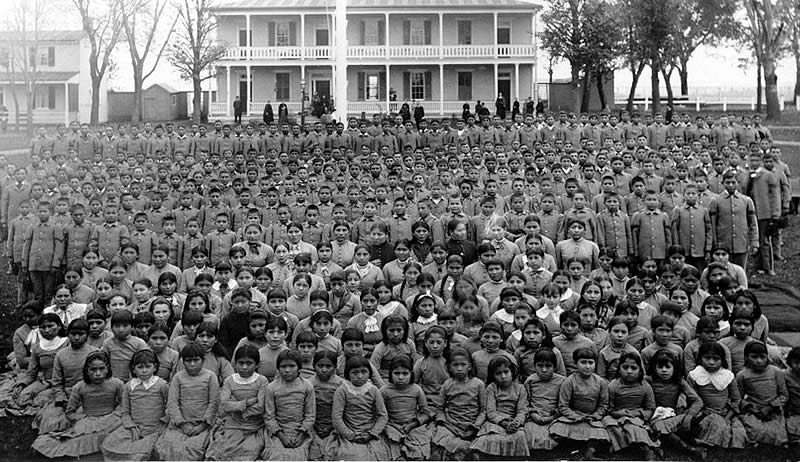

I do not hate the military. I do despise militarization and its impacts on men, women, children, and the land. The chilling facts are that the United States is the largest purveyor of weapons in the world, and that millions of people have no land, food, homes, clean air or water, and often, limbs, because of the military funded by my tax dollars. Countless thousands of square miles of Mother Earth are already contaminated, bombed, poisoned, scorched, gassed, bombarded, rocketed, strafed, torpedoed, defoliated, land-mined, strip-mined, made radioactive and uninhabitable. I despise militarization because those who are most likely to be impacted or killed by the military are civilian non-combatants. Since the Second World War, more than four fifths of the people killed in war have been civilians. Globally there are some 16 million refugees from war… I decided to write this book because I am awed by the impact of the military on the world and on Native America. It is pervasive. Native people have seen our communities, lands and life ways destroyed by the military. Since the first European colonizers arrived, the US military has been a blunt instrument of genocide, carrying out policies of removal and extermination against Native Peoples. Following the Indian Wars, we experienced the forced assimilation of boarding schools, which were founded by an army colonel, Richard Pratt, and which left a history of transformative loss of language and culture. The modern US military has taken our lands for bombing exercises and military bases, and for the experimentation and storage of the deadliest chemical agents and toxins known to mankind. Today, the military continues to bomb Native Hawaiian lands, from Makua to the Big Island, destroying life. The military has named us and claimed us. Many of our tribal communities are named after the forts that once held our people captive, and in today’s military nomenclature Osama bin Laden, the recently killed leader of al Qaeda, was also known as “Geronimo EKIA” (Enemy Killed in Action). Harlan Geronimo, an army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam and is the great grandson of Apache Chief Geronimo, asked for a formal apology and called the Pentagon’s decision to use the code name Geronimo in the raid that ended with al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden’s death, a “grievous insult.” He was joined by most major Native American organizations in calling for a retraction and apology. The Onondaga nation stated, “This continues to personify the original peoples of North America as enemies and savages. . . . The US military leadership should have known better.” The analogy from a military perspective is interesting. At the time of the hunting down of Geronimo, over 5,500 military personnel were engaged in a 13-year pursuit of the Apache Chief. Geronimo traveled with his community, including 35 men and 108 women and children, who in the end surrendered in exhaustion and were met with promises that were never fulfilled. It was one of the most expensive and shameful of the Indian Wars… The military, it seems, is comfortable with this ground. Indeed, Native nomenclature in the US military is widespread. From Kiowa, Apache Longbow and Black Hawk helicopters to Tomahawk missiles, the machinery of war has many Native names. (The Huey helicopter―Bell UH-1 is the Iroquois, and the Sikorsky helicopters are also known as Chickasaw, Choctaw and Mohave helicopters.) As the Seventh Cavalry invaded Iraq in 2003 in the “Shock and Awe” campaign that opened the war, one could not help note that this was the name of the cavalry division that had murdered 300 men, women and children at Wounded Knee. Yet, despite our history and the present appropriation of our lands and culture by the military, we have the highest rate of military enlistment of any ethnic group in the United States. We also have the largest number of living veterans out of any community in the country. We have borne a huge burden of post traumatic stress disorder among our veterans, and continue to feel this pain today, compounded by our own unresolved historic grief stemming from colonization. In this book, I consider the scope of our historic and present relationship with the military and discuss economic, ecological and psychological impacts. I then examine the potential for a major transformation from the US military economy that today controls much of Indian Country to a new community-centered model that values our Native cultures and traditions and honors our Mother Earth… — Take Action Sign the petition and see what else you can do to stop Line 3 and support Water Protectors: https://www.stopline3.org/biden While on the topic of Indigenous issues, there is a renewed campaign to free Native American activist Leonard Peltier from prison. Read about his story and, if you are moved to do so, support the Leonard Peltier Freedom Ride 2021 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources LaDuke, Winona. The Militarization of Indian Country. Michigan University Press, 2012. LaDuke, Winona. “LaDuke: Stop the Indian wars, and make new history.” InForum. 28 September 2022. https://www.inforum.com/opinion/columns/laduke-stop-the-indian-wars-and-make-new-history — Further Resources Honor the Earth: a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues. https://www.honorearth.org/ White Earth Land Recovery Project: reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people. https://www.welrp.org/ The following piece was originally posted in November 2020 to explain how American prejudices and historical ignorance has led to extermination campaigns of Native peoples, how American racist policies directly inspired Nazi practices, and how those ideas continue to influence American society and threaten minority groups. As we roll into Election Day next week, consider sharing this piece to start conversations and educate people on the topic. The following has been lightly edited from the original.

— November is Native American Heritage Month, and Thanksgiving is just one week away. While Thanksgiving is a holiday fraught with a problematic history, it is also ostensibly a day to thank Native American contributions to the history of the United States. But of course, many of us are canceling Thanksgiving plans this year to keep our families safe as the covid-19 pandemic surges across the country. And with President Trump still refusing to concede the election and instead continuing to promote baseless conspiracy theories, some might think that it is a mistake to focus so much attention on the social representation of a small minority population at such a crucial time. A lack of accurate, positive representation leads to a reliance on easily manipulable and usually negative stereotypes, which in turn leads to the systematic dehumanization of the minority group. Combined with other societal narratives of “natural” entitlement and being threatened on all sides, this deadly mix has historically led to genocides. Indeed, both the means and the reasons used by the Nazis to perpetrate ethnic cleansing in Eastern Europe were inspired by the American conquest, cleansing, and forced resettlement of the American Indians of the Western United States. During the “Indian Wars” between 1846 and 1890, the U.S. massacred countless Native peoples and forced the rest onto “reservations” of unwanted tracts of land in order to open up desirable land for settlers. One way or another, Native peoples were expected by white Americans to be “eliminated” or else to “disappear” on their own. Not too long ago, these atrocities were celebrated as advancements in human progress, not just in the United States, but in Nazi Germany. According to Carroll P. Kakel, III, Hitler conceived of the German war in Eastern Europe as a colonizing war of ethnic cleansing to remove Slavic and Jewish peoples to make way for lebensraum, “living space” for Germans. Hitler himself encouraged his close associates to “look upon the natives [of Eastern Europe] as ‘Redskins’” of the American West. If the endgoal of both colonial wars was the removal of the Other to make space for white or German settlers, then the concentration camps of the Holocaust can be seen as an upgraded, more efficient Native reservation. Of course, the entire process of conquering and destroying Native peoples in the American West was just a small part of the massive racist project in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. James Q. Whitman has pointed out that Nazi Germany repeatedly found inspiration in restrictive American racial laws, not only with respect to Black Americans, but with all other non-“nordic” peoples. In fact, in the early 20th century, the United States led the world in racist law -- at least in the eyes of the Germans, Brazilians, Australians, and South Africans who implemented infamously racial codes in their own countries modeled after the American ones. As Whitman points out, Nazis themselves had a difficult time finding other models for racist codes like anti-miscegenation laws, except in the case of the “classic model” of the United States, where there was a robust tradition of forced segregation, restrictive racial immigration quotas, and second-class citizenship. Perhaps it is shocking to learn that the Nazis themselves were inspired by the American treatment of Indigenous, Black, and other non-white peoples. Most Americans do not associate the United States with fascism or Nazism -- we fought them, after all, didn’t we? Some have heard that prominent American figures like Henry Ford and Walt Disney were Nazi sympathizers before the attack on Pearl Harbor, but generally consider such information as curious details of eccentric tycoons during “a different time” in history. Some have even heard of the American Nazi rally in 1939 that attracted more than 20,000 people to Madison Square Garden. But most Americans would likely deny that any genocides have ever occurred in the United States -- not out of denialism, but out of historical misunderstanding and confusion about what genocides actually are. But then there are also those who believe in the “white genocide” myth, or the “Great Replacement” variation. The conspiracy theory is shockingly popular in some form or another among white conservatives and reveals the anxieties over ethnic diversity and the atrocities committed upon People of Color. Those who believe the “white genocide” myth fear that, given the chance, African-Americans would start a race war to exterminate white people out of revenge for slavery, disenfranchisement, terror, and more. The “Great Replacement” idea is more subtle, stating that unending waves of immigration into Western countries like the United States will lead to the rapid growth and spread of non-white people, ultimately ending in the “replacement” and erasure of whiteness and Western culture. Both of these variations often point to some shadowy group directing these massive demographic shifts specifically to exterminate white people. Strangely, these imaginary “globalist” or “New World Order” groups are usually composed of Jewish people. The United Nations defines “genocide” as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

Since there is no secret group imposing such policies on “white people” generally, and Black Americans time and again have faced violence with resolute nonviolent action. Those conspiracy theories are pure fantasy, but even entertaining them can be dangerous. If the precieved threat is as existential as death, replacement, and erasure, then the logic of those fantasies must always end with a kind of preemptive genocide or other atrocity to “protect” the “white race.” This is exactly the logic that led many ordinary Germans to look away from the worst atrocities their government committed upon Jewish, Slavic, and other peoples. It’s the logic that excuses separating children from their parents and locking them in cages today. It’s the logic that makes a threat out of any Black man, and what lets their murderers escape justice time and again. The online series The Man in the High Castle, based on the novel by Philip K. Dick, takes place in an alternate 1960s in which the Axis powers won the Second World War. At one point in the series, a white asylum seeker studies with a Hitler Youth to become a naturalized citizen of The Greater Reich, which spans most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. As they study, the Hitler Youth brings up a question “about American exterminations before the Reich.” The asylum seeker asks with confusion, “exterminations?” to which the Hitler Youth replies almost with amusement: “Didn’t they ever teach you about the Indians?” Let’s just make sure we get the story straight. — Sources and Further Reading: Cochran, David Carroll. “How Hitler found his blueprint for a German empire by looking to the American West.” Waging Nonviolence, 7 October 2020. https://wagingnonviolence.org/2020/10/hitler-found-blueprint-german-empire-in-the-american-west/ “Genocide.” United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide.shtml Kakel, Carroll P. The American West and the Nazi East: A Comparative and Interpretive Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Schwartzburg, Rosa. “No, There Isn’t a White Genocide.” Jacobin, 4 September 2019. https://jacobinmag.com/2019/09/white-genocide-great-replacement-theory Whitman, James Q. Hitler's American Model: the United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press, 2018. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed