|

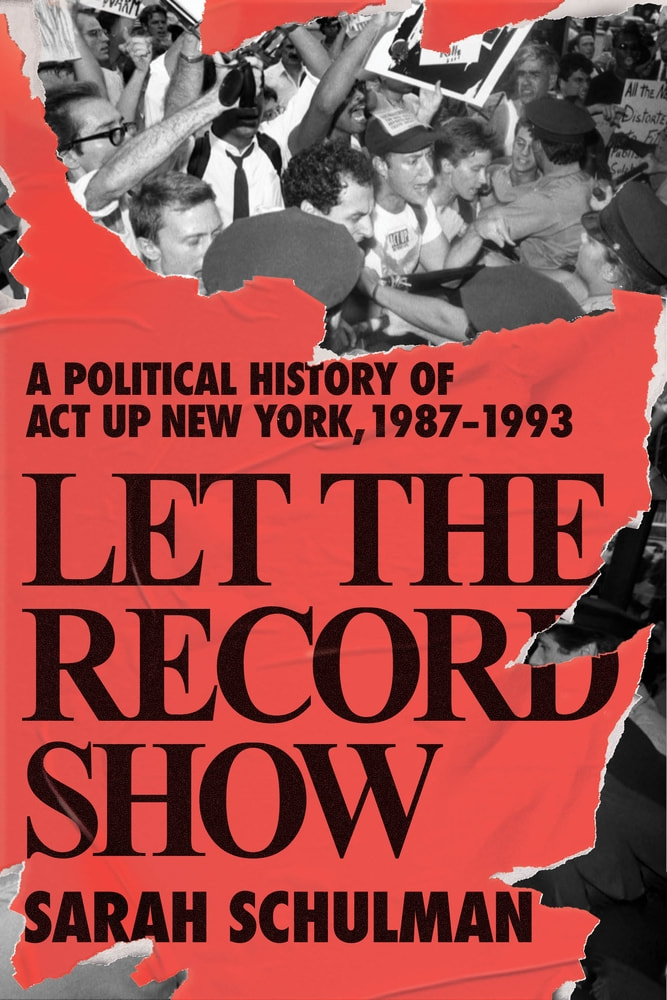

In observance of World AIDS Day, here we have two excerpts about Jamie Bauer: a member of ACT UP who directly helped shape the organization. Jamie brought the protest tactic of nonviolent civil disobedience to ACT UP, training members who went on to train even more — rippling out to an enormous scale. According to many within the movement, it was nonviolent civil disobedience which largely made ACT UP so successful. Jamie Bauer had been influenced by Barbara Deming, a feminist lesbian activist and writer who had been involved in the antiwar group the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA), which founded the original Voluntown Peace Trust. Jamie was also active with the Women’s Pentagon Action, which was supported by the War Resisters League (WRL). Because of that connection, Jamie knew WRL staff member David McReynolds, and the two ran a training that influenced ACT UP to use nonviolent tactics. David McReynolds also worked with Barbara Deming in both CNVA and WRL (learn more from Martin Duberman’s book A Saving Remnant: the Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds). By the time Jamie Bauer was getting involved with ACT UP, the CNVA had merged into WRL. The closer one looks, the more direct connections one can see between ACT UP, the antiwar movement, the civil rights movement, and many more of the time. In 2020, T: The New York Times Style Magazine interviewed 12 veteran activists of ACT UP to tell their experiences in the organization in their own words. Jamie Bauer was one of the members interviewed, and we have shared their words below. In 2021, a book was published about this period: Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman. Chapter 16 of the book is about the role of civil disobedience in ACT UP, and Jamie Bauer is a central figure throughout. Below, we share excerpts from the beginning of the chapter (find the source link at the end of this post to find your own copy and read the whole story for yourself). --

From “12 People on Joining ACT UP: ‘I Went to That First Meeting and Never Left’” in T: The New York Times Style Magazine JAMIE BAUER, 61 Joined in 1987 In 1981, I became active in the Women’s Pentagon Action, which is a feminist, anti-militarist group with connections to the War Resisters League (WRL), one of the oldest pacifist organizations in the United States. I was trained in nonviolent civil disobedience: We would discuss a demonstration and really walk through the safety of it to make sure that we weren’t doing anything to intentionally hurt people. When ACT UP started in 1987, some of the organizers of the first meeting reached out to the WRL. David McReynolds, a longtime member, and I dispatched WRL members who understood nonviolent civil disobedience — and that included the two of us, both queer — to go to the ACT UP meeting and do a brief training. After that, I just stuck with it. As a pacifist, for me, it was always about acknowledging your anger and channeling it into something productive — and, of course, with people dying, there was so much anger. Although ACT UP did not take a vow of nonviolence, we had a series of principles that were built upon that; we had very clearly drawn lines. For me, the biggest struggle was working with people to make sure that we didn’t overstep those boundaries, that we didn’t turn into the Weathermen [the ’60s and ’70s-era radical faction of the left-wing Students for a Democratic Society], that we didn’t bomb buildings — which, in a time of desperation, when you’re watching all your friends die, would have been an easy direction for us to go in. -- From Chapter 16: The Culture and Subculture of Civil Disobedience in Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman The most influential cohering experience in values inside ACT UP that almost everyone shared was civil disobedience training, and thousands of people experienced it together. Although based in an applied practice with tips and guidelines, all of the instructions were rooted in a very articulate and deep ethical belief system about community. The trainers became a moral center of this culture, profoundly influential on the movement as a whole, and specifically consequential on the individuals who shared this preparation and subsequent experience of nonviolent defiance. JAMIE BAUER Jamie Bauer grew up in Stuyvesant Town, in Manhattan. Their father was a salesman, and their mother was a homemaker. After Hunter High School they went to MIT to study civil engineering, architecture, and urban planning, and earned a master’s in transportation, which had a one-in-eight women-to-men ratio. Jamie found the program to be not very intellectual. “Rigorous, but not very interesting.” Although there was a small gay student union at the school, it was all men. On the other hand, MIT was in Boston, which had a huge lesbian community. And so Jamie came out pretty quickly and start making some connections into the mixed gay movement and into the lesbian movement, the two of which were still somewhat separate at that point. In 1981, they returned to New York to work for the MTA, eventually as director of subway schedules. About two decades after their time in ACT UP, Jamie started to live as nonbinary. In the early 1980s, Jamie had heard a lot about the Women’s Pentagon Action, a mobilization to create a large women’s peace action directly confronting the Pentagon. They went to a couple of meetings and got hooked, “because these women were so interesting and so smart and creative, and knew so much. And I just thought—Well I’m just going to sit here and hang out and absorb this.” Jamie worked with Grace Paley, Vera Williams, Eva Kollisch, Donna Gould, Sharon Kleinbaum, Toni Fitzpatrick, Laura Flanders, Harriet Hirschorn, and other women peace activists. The group came together to make the connections between war, the patriarchy, women’s oppression, the military–industrial complex. It was also an antinationalism group. They did not believe in borders, flags, or patriotism, and believed that women bonding together with other women could save the world. And at that time, 60 to 75 percent of the group were lesbians, but that fact was not acknowledged. “It wasn’t part of the dogma of the group. We were women—which I found a little hard to stomach, because it was so clear that so many [of the] women were lesbians anyway, but they didn’t want it to be a lesbian group.” Jamie learned a lot about organizing, dealing with the police, insisting on the right to take space, and just everything about doing politics on the street.[...] Influenced by the writings of Barbara Deming, Jamie picked up the concept that people have a right to free speech and freedom of assembly and should not have to ask permission for it. And if the state wanted to arrest us for it, that was their business, but the people were not going to ask the state’s permission. So it was nonviolent civil disobedience rooted in an insistence on people protecting their rights by using them, and not letting the government take those rights. When they first came to ACT UP, Jamie found it all very exciting. People were so charged up and just wanted to demonstrate, demonstrate, demonstrate. ACT UP would schedule five demonstrations in a week, and then the members would go to all of them. But Jamie found that they didn’t know anything about demonstrating. For example, at the first Wall Street demo, ACT UP gave the police a list of the seventeen people who were going to be arrested, and each person who was going to be arrested wore an armband so that the police wouldn’t accidentally take the wrong person. Jamie felt that this was overly orchestrated and made it impossible for anybody else to try to jump in. Jamie called this “Celebrity CD [civil disobedience]. They didn’t want three hundred people, at that point, necessarily doing CD. They wanted a couple of name people, with recognition so that would be what would be in the press.” Jamie understood that ACT UP was trying to figure out how to use its anger, because it was a group with a tremendous amount of rage and anger at the system. Although New York City was the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic, the federal decision-makers were in Washington. It was very frustrating to go out into the streets of New York and demonstrate, because they were demonstrating against buildings that people in power weren’t necessarily in. For Jamie, civil disobedience is an American tactic that people understand, in some ways. But Jamie had a particular commitment to a concept of safety. There were people who didn’t understand issues of public safety, personal safety, the safety of the community, or taking responsibility for one’s actions. Jamie and the other trainers really began to talk about civil disobedience as a safe tactic for making a stronger, direct, personal statement, and as a way of getting media attention. They tried to get everybody in the group trained for civil disobedience, because no one always knows when it’s going to happen, or when they’re going to want to do it. When dealing with the police, no organizers can guarantee people’s safety; there are a lot of things that can make it physically safer than just haphazardly running out into the street.[...] — Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. Macmillan: 2021. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374185138/lettherecordshow Turner, Kyle. “12 People on Joining ACT UP: ‘I Went to That First Meeting and Never Left’”. T: The New York Times Style Magazine, published 13 April 2020 (updated 17 April 2020). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/t-magazine/act-up-members.html — Further Reading Duberman, Martin. A Saving Remnant: the Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds. The New Press: 2012. https://thenewpress.com/books/saving-remnant Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed