|

One hundred and four years ago to the day, Jeannette Rankin was seated as the first woman member of the US Congress. In her two nonconsecutive terms representing Montana, Rankin caused intense controversy for her work in the women’s suffrage movement, for her efforts to secure protections for workers, and most of all for her outspoken opposition to war. The uncompromising stance that she maintained over several decades on such controversial issues inspired many of her peers, inspired many the younger generation in the 1960s and ‘70s, and continues to inspire those who work against the grain in order to improve society for all.

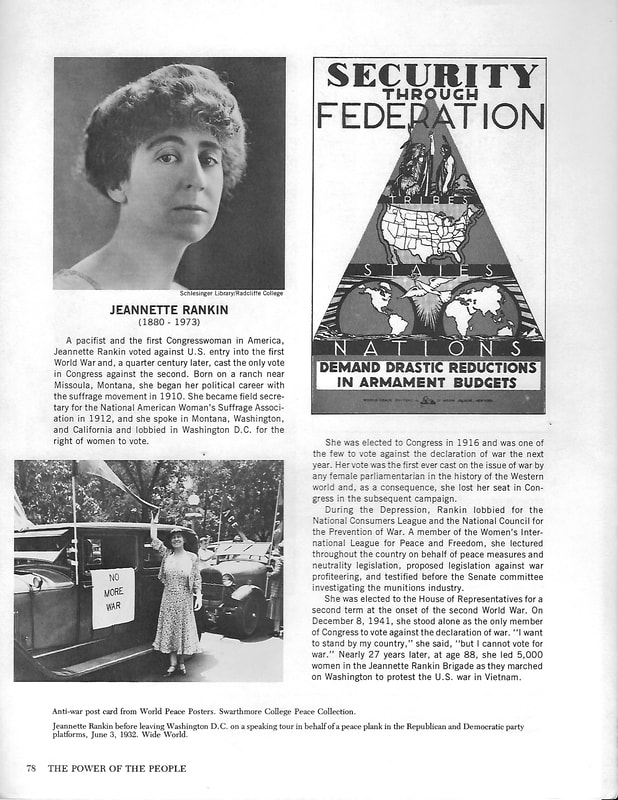

Up until well into her twenties, Jeannette Rankin lived a fairly sheltered life in rural Missoula, Montana. She earned a Bachelor of Science in biology from the University of Montana in 1902, then worked as a teacher and a seamstress before becoming a caretaker for her sick father. It was not until 1904 that Rankin witnessed her first glimpses of urban, industrial poverty alongside unimaginable extravagance and wealth during a visit to the east coast. Returning home, Rankin began to read all the material she could find on progressive ideas, especially the issues related to women. After seeing the same inequality in San Francisco during another trip in 1907, Rankin was compelled to move to the city to teach recently-arrived immigrants at a private settlement house, then moved to the east coast to attend the New York School of Philanthropy in 1908. After graduating, Rankin moved back west to Washington state and became involved in the women’s suffrage campaign in Seattle. After the campaign was won in 1910, making Washington the fifth state in the Union to extend voting rights to white women, Rankin got a job as a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), traveling across the country to organize local women’s suffrage campaigns. Following the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, which killed 146 garment workers in New York City, Rankin also organized the immigrant women still working in similarly dangerous conditions in Manhattan’s Garment District. Meanwhile, Rankin led a revival of the women’s suffrage movement in Montana starting with a speech before the Montana legislature in 1911 -- the first woman to address the Montana legislature. The state legislature would pass a bill expanding voting rights to white women in 1913, and the public voted in favor of a women’s suffrage referendum in 1914, making Montana the 13th state in the Union to legalize women’s suffrage and the second women’s suffrage campaign that Rankin helped carry to victory. Hoping to build off of the landmark victory in her home state, Jeannette Rankin declared her candidacy for a Congressional seat representing Montana in 1916. Her platform followed a typical progressive slate including universal suffrage, child welfare legislation, and alcohol prohibition. Less universal among progressives was her outspoken opposition to US involvement in the First World War. But despite promoting what some may have thought were radical positions at the time, and despite being ignored by most of the newspapers in the state, Rankin won the second-most number of votes in Montana that year, becoming the first woman to be elected to Congress in the United States. Many women voters who knew the work Rankin had already done for them cast their votes for her, but Rankin’s modern, progressive platform convinced enough male voters as well that she beat the next runner-up by 6000 votes. On her first day as a House Representative, Rankin introduced the Susan B. Anthony amendment to guarantee and protect women’s suffrage in the US Constitution. Later that same evening, President Wilson requested Congress to declare war on Germany to make the world “safe for democracy.” In the days between Wilson’s request and the actual vote, Rankin’s colleagues and even her brother Wellington advised her to go against her personal feelings and vote in favor of the war. But she was not alone in her opposition to entering the war: the majority of the messages she received from her constituents in Montana urged her to vote against war, and 49 other House members also planned to vote against. Rankin apparently considered abstaining, but ultimately cast her vote, saying, “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.” The reaction was mostly negative and singled out Rankin despite the many other men who voted with her. In a parallel to civil rights leaders who expressed antiwar sentiments later on, Rankin was accused by some of her allies of sabotaging the broader women’s suffrage movement with her personal opinions. Still, Rankin continued leading the universal suffrage cause as the only woman in Congress. She was a founding member of the Committee on Woman Suffrage and continued to passionately argue for the Susan B. Anthony amendment. At one point, Rankin addressed the hypocrisy of Congress with regards to war and democracy: “How shall we explain to them the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted for war to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?” The measure was ultimately passed as the Nineteenth Amendment the year after her term ended. During her first term, Rankin also investigated accounts of worker abuse in government bureaus, as well as in the industries that encouraged the United States to join the war in the first place. In the two decades after her first term in Congress, Jeanette Rankin continued some of that work within a number of local, national, and international progressive organizations. She worked as a lobbyist, a field secretary, and traveling speaker, advocating for social welfare, increased education, and worker and consumer protections. When Senator Gerald Prentice Nye published his “merchants of death” investigation into powerful US arms manufacturers and their role in dragging the country into the First World War, Rankin publicized the findings. Those arms manufacturers had only grown in the last couple decades, and seemed to be sending the United States on another warpath. Eventually, the imminent threat of another war led Rankin to run in the Montana elections in 1940 and defeat her anti-Semitic opponent for the House seat. Early in her second term in Congress in 1941, Jeannette Rankin unsuccessfully introduced legislation to limit the range of the US military, hoping to make it legally impossible to join the brewing global conflict. On the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor later that year, unlike in her last term, Rankin was the sole member of both houses in Congress to vote against declaring war. The reaction to her vote was so intense that afterward, Rankin was forced to take refuge in a phonebooth while reporters and other Congress members harassed her; she ultimately had to be escorted out by police. The vote effectively ended her political career, but after her second term, Rankin continued to travel and learn. She became more aware of the global decolonization movement, went to India several times to learn Gandhian nonviolent resistance, and continued to speak out against war and exploitation. In the 1960s, as the United States involved itself more in the Vietnam War, a new generation of war resisters emerged. Rankin had purposely stayed out of the headlines since she left Congress, but the accelerating war in Vietnam pushed Rankin, now in her eighties, to participate in the new antiwar movement. In advanced age and suffering from a painful medical condition, Rankin nevertheless helped to organize a coalition of 5000 women and several women’s peace organizations to form the largest women’s march on Washington since the 1913 suffrage march. The Jeannette Rankin Peace Brigade, as it was named, included several women’s groups which emphasized the nurturing, protecting, and mourning roles of traditional mothers and wives. But the group also included a faction which called for the need to “bury traditional womanhood” and to draw feminine political power from new sources -- Rankin, herself, never married or became a mother, after all. As a trailblazer of women’s rights, a nonconformist in many ways, and a courageously consistent voice for peace and social justice, a great variety of women in the 1960s and ‘70s found inspiration in Jeannette Rankin. Indeed, as we today grapple with rollbacks of civil rights protections, worsening worker exploitation, the continual growth of the military-industrial complex, and an expansion of our endless wars, we may do well to look to Jeannette Rankin’s lifelong resistance to violence and injustice, and find inspiration ourselves. Sources: O’Brien, Mary Barmeyer. Jeannette Rankin 1880-1973: Bright Star in the Big Sky. Falcon Press Publishing Co., Inc., 1995. “Rankin, Jeannette.” History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives. https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/R/RANKIN,-Jeannette-(R000055)/ Smith, Norma. Jeannette Rankin: America’s Conscience. Montana Historical Society Press, 2002. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed