|

(click here to view the original post on Facebook)

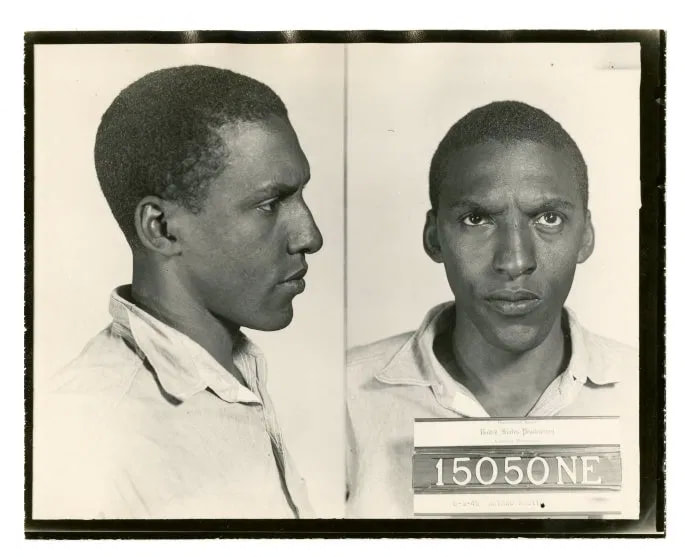

For this week’s Peace of History: In acknowledgment of Bayard Rustin’s 108th birthday and our recent theme of conscientious objection, we will highlight Rustin’s conviction and courage as a conscientious objector during WWII. Much has been done in the past couple decades to elevate heroic stories of African-Americans in the armed forces, as well as black veterans' roles in inspiring the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. But little has been shared of the stories of African-Americans who just as bravely refused compulsory military service at the same time, and who had laid the foundations for the civil rights movement before black vets came home en masse. As Matt Meyer with the War Resisters League wrote on Rustin’s centennial anniversary: “It is important first to note that, just as the foundations for much of the 1950s tumult around civil rights were laid by the Tuskegee Airmen and other members of the U.S. Armed Forces of African descent, Rustin was a part of another grouping of World War II veterans. When the black vets who helped liberate Europe from fascism and open the doors of the concentration camps came home to find that democracy and equality was not forthcoming despite their heroic efforts, Rustin and his World War II conscientious objector colleagues had spent their war years behind bars. Many of them, including Rustin, Dave Dellinger, Ralph DiGia, George Houser and Bill Sutherland, were active in efforts to desegregate the federal prisons they were held in, a daring effort 10 years before the widespread lunch counter sit-in and bus boycott campaigns.” Like many other conscientious objectors before him and since, Rustin was imprisoned from 1944-1946, for his refusal to register with the Selective Service Board. For Rustin, refusal to join the war effort was not merely about the injustice of war itself, but moreover, as he wrote in a letter to his local draft board in 1943: “Segregation, separation, according to Jesus, is the basis of continuous violence… Racial discrimination in the armed forces is morally indefensible.” According to Shaina Destine at the National Archives, Rustin’s prison file upon admission into Ashland Federal Correctional Institution on 1944 states: “...it is believed that this inmate will continue to bring up racial problems in this institution, as has been his practice before being committed here, and it is further indicated by his actions that he is already engaged in practices of agitating other inmates on the race problem. His adjustment in this institution is doubtful.” Indeed, before his arrest, Rustin had trained with the American Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia and had become involved in several racial justice efforts, including with the Harlem Ashram. (See the January 30th Peace of History for more on the Harlem Ashram.) As suspected, Rustin did not tone down his beliefs and behaviors much in prison. He was frequently disciplined for “arousing and agitating” the other prisoners about medical care, mail policies, and racial integration. From his prison file: “...this inmate objects to institutional ruling in not allowing Whites and Negroes to intermingle in so far as eating and sleeping is concerned. He will not walk in a line segregated or be segregated in the dining hall. Today at noon meal he came out with the Qurantive group but refused to line up with the Negroes, but instead started to deliver an oration on his opinions of segregation, etc. He was told to line up as required…but this he refused to do and then had to be excorted [sic] back to his cell.” In March 1946, Rustin began a hunger strike to protest racial segregation in prison. Support for Rustin among the prisoners and some sympathetic correctional officers broke when word of his homosexuality got out, but this did not break him. Rustin would go on to rack up ten disciplinary reports, finally forcing the Chief Medical Officer to designate Rustin as not “suitable for a correctional institute.” Rustin was transferred to a farm labor camp, but shortly after, Rustin was offered a conditional release with travel and publicity restrictions. He refused, citing his need for both freedoms to perform his job as field agent for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Some of these restrictions were removed. Yet, when the warden warned Rustin that he must at least try to conform to some of the other conditions for his release, Rustin refused again. In the end, the warden had to sign for him, and Rustin refused even the suit they had chosen for his release. Many have argued that WWII was a justified and necessary war for the United States to fight, and that the alternatives, fascist and imperial rule, were objectively worse. But Bayard Rustin’s resistance to participating in the Second World War highlights the essentially hypocrisy of U.S. involvement in the war: the fact that even while fighting Nazi racism abroad, America continued to racially segregate in the prisons and the barracks. Indeed, it was exactly this national cognitive dissonance, this mismatch of moral messaging and policy, that drove so many black vets to the post-war civil rights movement -- but it was conscientious objectors like Bayard Rustin who led the way. Next week: we will look into the government failure to respond during the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the grassroots organizing that gave rise to direct action groups like ACT UP. Sources: Destine, Shaina. “Bayard Rustin: The Inmate that the Prison Could Not Handle.” https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2016/08/16/bayard-rustin-the-inmate-that-the-prison-could-not-handle/ Mascari, John. “U.S. Conscientious Objectors in World War II.” https://www.friendsjournal.org/u-s-conscientious-objectors-world-war-ii/ Meyer, Matt. “Remembering Bayard Rustin at 100.” https://wagingnonviolence.org/2012/03/revisiting-rustin-on-his-centennial/ Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed