|

For this week’s Peace of History:

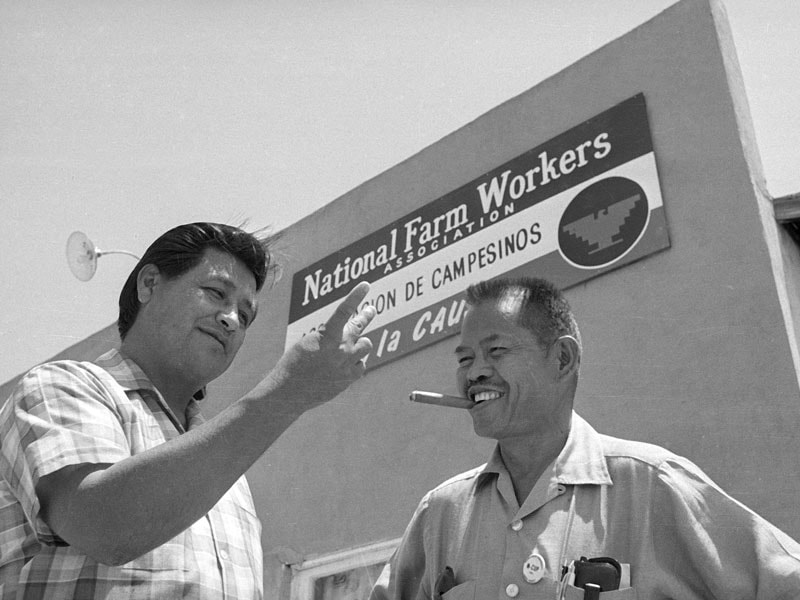

Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of the successful end of the 5-year Delano Grape Strike, which saw the formation of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW) and the rise of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta as legendary figures in the labor movement. And yet much has been forgotten, written out, or otherwise misunderstood about why the strike started in the first place, who was involved, how it succeeded, and what followed. Too often, key pieces of contextual history are excluded from the telling of a story. A more complete history of the founding of the UFW must include the story of Larry Itliong’s leadership, the initial unity of the Filipino-American manong generation and Mexican-American farm workers, and the dangers of placing too much power in the hands of a single person. To understand the Delano Grape Strike, we must trace back two separate lines, how they came together, and why they frayed apart. Following the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), the United States aggressively colonized the Philippines on multiple fronts. As a result of colonization, from 1917 to 1934, the tens of thousands of Filipino immigrants to the United States in the early 20th century did not face the heavy immigration restrictions that other Asians received, and many Filipino immigrants did not initially feel like such outsiders. Upon immigrating, however, Filipinos often suffered racist violence, prejudice, and segregation. It was not unknown for bosses to physically whip and beat Filipino workers, call grown men “boys,” and perform other acts of dehumanization. Moreover, in 1934, Congress changed immigration laws to change the status of all Filipino-American citizens to “alien,” and to restrict new Filipino immigration similarly to other Asians. Furthermore, anti-miscegenation laws prevented “Whites” (including most Hispanics) from marrying “Blacks,” “Asians,” and after 1930, “Filipinos.” With a gender disparity of 14 men to 1 woman in Filipino immigration in the early 20th century, this lost generation of mostly unmarried men became known as the manong (“older brother”) generation to later Filipino immigrants. The manong formed alternative communities and economies based both on their Ilocano Filipino heritage and on the new itinerant lifestyles many had adopted in the United States. While some Filipinos came to participate in American universities, the vast majority were young men seeking migrant manual labor. These mostly male communities dotted along the west coast and relied as much on the migrant Filipino agricultural workers as the workers did on these communities. Through years of traveling, working, eating, and sleeping side-by-side together, the manong developed a strong group identity and mutual trust with each other. Thus, they also started organizing as workers in the face of racist exploitation early on. When Larry Itliong immigrated to the United States in 1929 at the age of 15, Itliong found manong already starting to organize, and he quickly got involved. Over the years, Itliong helped to organize cannery and agricultural workers unions from Alaska’s dangerous fisheries in the north to California’s massive plantations in the south. Larry Itliong became known among the other manong for his charisma, militance, and skill in organizing. The 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s saw frequent, sometimes violent resistance from Filipino laborers in the United States, which was often successful at winning higher wages and other short-term concessions, but never resulted in written contracts with codified improvements. At first, the Delano Grape Strike in 1965 seemed to follow the pattern. The predominantly Filipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) led by Larry Itliong had won a strike months earlier in May against Coachella Valley grape growers ended with the typical results: no contract. Moving north to Delano in September, Filipino workers asked the AWOC to help organize a strike to win the same wages as in Coachella Valley. The strike began on September 8. Mexican-American workers, however, had also migrated into the area, and could easily provide the scab labor for the grape growers -- another pattern which had previously often led to Filipino workers physically confronting and fighting Mexican-American workers. But this was 1965: Dr. King’s message of interracial harmony, equal justice, and nonviolent methods were world-famous. Things were different now. And besides, by this time, most of the manongs were in their 50s and 60s, their bodies weathered by decades of manual labor -- Larry Itliong himself had years ago lost three fingers in a fishing accident. Itliong evaluated the situation carefully. Around the same time, Mexican-American workers on the west coast were starting to organize. The bracero federal workers program had ended in 1964, opening up more opportunities for Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to organize primarily Mexican-Americans working in agriculture. Chavez dreamed of leading a Chicano movement, with labor a key component. Huerta had already demonstrated her skill in community organizing with her work improving conditions in barrios, and looked to the farm workers as the next step. The two formed the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) in 1962, grew the membership rapidly, and in April 1965, helped to organize a short, successful strike for rose grafters. The NFWA’s reputation was growing steadily, but Chavez himself felt that they would not be ready for a large-scale strike for at least another three years. And yet, when Larry Itliong approached Chavez personally to join the strike, Chavez felt backed into a corner. The issue was put to a vote with the NFWA, and on September 16, Mexican Independence Day, an overwhelming majority of the more than twelve hundred of his union members voted in support of the Filipino workers. For years after, Mexican and manong workers alike picketed together, ate or went hungry together, and slept on the same dusty cold floors together. With the NFWA’s superior numbers, Chavez quickly took over organization of the strike, sending representatives to the Longshoremen to convince them not to pack grapes. Soon, the United Automobile Workers pledged financial support to the strikers. Inspired by the boycott tactic popular in the Civil Rights Movement, Chavez met with SNCC to learn their methods and foster an alliance. They started a national boycott of California grapes, with Dolores Huerta coordinating a campaign that sent hundreds of strikers across the country to share their stories. Chavez eventually led a 300-mile march from Delano to Sacramento to draw attention to the farm workers’ plight. The message was simple and clear: tens of thousands of strikers are making enormous sacrifices to secure labor justice and dignity as workers -- but average Americans can help by making the small sacrifice of abstaining from grapes. Unlike many of the boycotts of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, which were usually focused on local or regional businesses, the farm workers’ boycott campaign brought distant struggles for justice into countless grocery stores and suburban homes. This strategy proved to be particularly effective, and laid the groundwork for the success of future national boycotts like the Lettuce Boycott of 1970-1971 and the Gallo Wine Boycott of 1973-1978. About a year into the strike, the AWOC and the much larger NFWA merged to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, later known as the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), with Chavez as General Director and Itliong as Assistant Director. It was well-known, however, that Chavez organized around himself as a “one man union” with a few close, ambitious, like-minded confidantes like Huerta to carry the rest of the responsibilities. Itliong and other Filipino labor leaders found themselves a “minority within a minority,” filling largely symbolic roles in a union that increasingly seemed to forget about the very workers who started the strike in the first place. After five long years, in July 1970, the UFW won the strike over the Delano grape growers, and a contract for the agricultural workers specifying codified rules to improve conditions in the fields -- a first for the manong. But provisions negotiated by Chavez and Huerta also implemented hiring systems that drastically disrupted manong communities, many of whom still had no families or savings for support. The concerns of these aging Filipino men were increasingly ignored as they became a smaller and smaller minority in an organization they helped found. Chavez appointed Itliong the National Boycott Coordinator of the UFW in 1970, but Itliong increasingly felt uncomfortable with his own unelected position and how Chavez ran the union. In 1971, Itliong resigned from the UFW, citing the lack of concern for the manong workers and Chavez’ particular leadership style as his reasons. A key figure in the Asian American Movement, Larry Itliong continued to organize and advocate for his fellow manong workers until his death in 1977. Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez went on to become powerful figures in the labor and Chicano movements, and undoubtedly effected positive changes for countless workers. Utilitarianism posits that whatever effects the greatest good for the greatest number of people is the most ethical choice -- under such an analysis, the UFW’s victory in the Delano Grape Strike was an overwhelming success. But at the same time, many manong concerns were neglected, and some ended up worse off than before. As we build up our own groups and form coalitions, let us not repeat the mistake of the UFW. Let us remember the minority within the minority. Sources: “The 1965-1970 Delano Grape Strike and Boycott” https://ufw.org/1965-1970-delano-grape-strike-boycott/ “‘A Minority Within a Minority’: Filipinos in the United Farmworkers Movement” https://prizedwriting.ucdavis.edu/sites/prizedwriting.ucdavis.edu/files/sitewide/Barbadillo_vol28.pdf “COACHELLA VALLEY: Filipinos’ 1965 strike set stage for farm labor cause” https://www.pe.com/2005/09/03/coachella-valley-filipinos-1965-strike-set-stage-for-farm-labor-cause/ The Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the UFW https://www.pbs.org/video/kvie-viewfinder-delano-manongs/ Dunne, John Gregory. Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike. 1971 https://books.google.com/books?id=GQ1JkSnNmLQC&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false Jiobu, Robert M. Ethnicity and Assimilation: Blacks, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Japanese, Mexicans, Vietnamese, and Whites. 1988 https://books.google.com/books?id=VJa9SDpTfzEC&pg=PA49#v=onepage&q&f=false “The Forgotten Filipino-Americans Who Led the ’65 Delano Grape Strike” https://www.kqed.org/news/10666155/50-years-later-the-forgotten-origins-of-the-historic-delano-grape-strike “Forgotten Hero of Labor Fight; His Son’s Lonely Quest” https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/19/us/larry-itliong-forgotten-filipino-labor-leader.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed