|

Today is Veterans Day here in the United States — better known as Armistice Day or Remembrance Day throughout much of the world. In the past, we have used this holiday to draw comparisons between the United States and much of the rest of the world. But this year, we are turning inward to examine how the US military has affected one specific racial category within the United States itself: Native Americans.

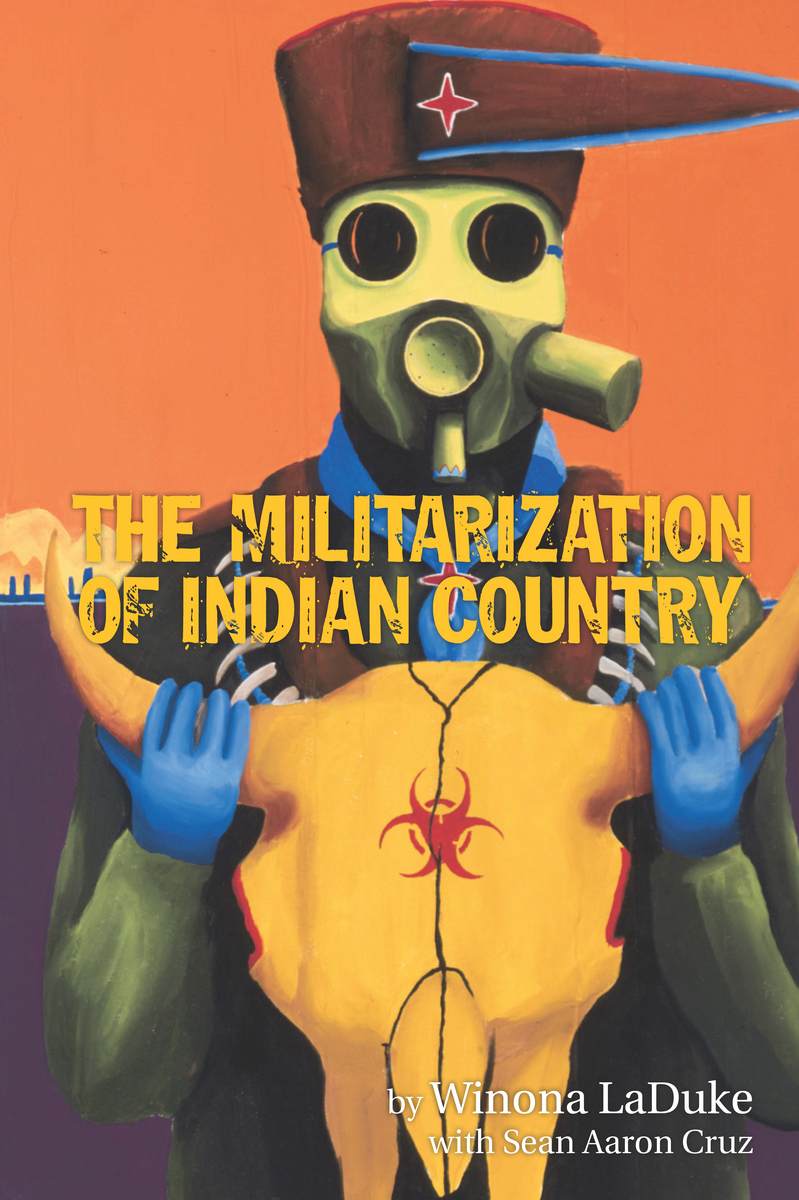

Winona LaDuke is a Native American Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) activist-economist who is known for her involvement in many large projects: the White Earth Land Recovery Project, which reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people; Honor the Earth, a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues; and most recently, the Line 3 pipeline protests that seek to prevent enormous ecological disasters in Native lands. In her 2013 book The Militarization of Indian Country, LaDuke explores several dimensions of the intersection of Native peoples and the US military, from historical seizures of Native land by the military, to contemporary post-traumatic stress disorder of Indigenous veterans, to glimmers of hope and peace in the future. As LaDuke alludes in these excerpts, the relationship between the US military and Native American peoples is complex and fraught. On the one hand, the military offered to many Native Americans a ticket out of desperate circumstances: the impoverished reservation, the horrifying residential schools, the abusive adoptive family, and other awful situations to which so many Native people had been subjected. On the other hand, it was precisely the US military that drove so many recent Native ancestors from their homes, violently fractured countless Native communities and families, and then appropriated Native names to describe the US military’s bases (all on occupied land), weapons and vehicles (inanimate death machines), and most problematically, enemies (nameless, faceless, irrational “Others”). — [...] I do not hate the military. I do despise militarization and its impacts on men, women, children, and the land. The chilling facts are that the United States is the largest purveyor of weapons in the world, and that millions of people have no land, food, homes, clean air or water, and often, limbs, because of the military funded by my tax dollars. Countless thousands of square miles of Mother Earth are already contaminated, bombed, poisoned, scorched, gassed, bombarded, rocketed, strafed, torpedoed, defoliated, land-mined, strip-mined, made radioactive and uninhabitable. I despise militarization because those who are most likely to be impacted or killed by the military are civilian non-combatants. Since the Second World War, more than four fifths of the people killed in war have been civilians. Globally there are some 16 million refugees from war… I decided to write this book because I am awed by the impact of the military on the world and on Native America. It is pervasive. Native people have seen our communities, lands and life ways destroyed by the military. Since the first European colonizers arrived, the US military has been a blunt instrument of genocide, carrying out policies of removal and extermination against Native Peoples. Following the Indian Wars, we experienced the forced assimilation of boarding schools, which were founded by an army colonel, Richard Pratt, and which left a history of transformative loss of language and culture. The modern US military has taken our lands for bombing exercises and military bases, and for the experimentation and storage of the deadliest chemical agents and toxins known to mankind. Today, the military continues to bomb Native Hawaiian lands, from Makua to the Big Island, destroying life. The military has named us and claimed us. Many of our tribal communities are named after the forts that once held our people captive, and in today’s military nomenclature Osama bin Laden, the recently killed leader of al Qaeda, was also known as “Geronimo EKIA” (Enemy Killed in Action). Harlan Geronimo, an army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam and is the great grandson of Apache Chief Geronimo, asked for a formal apology and called the Pentagon’s decision to use the code name Geronimo in the raid that ended with al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden’s death, a “grievous insult.” He was joined by most major Native American organizations in calling for a retraction and apology. The Onondaga nation stated, “This continues to personify the original peoples of North America as enemies and savages. . . . The US military leadership should have known better.” The analogy from a military perspective is interesting. At the time of the hunting down of Geronimo, over 5,500 military personnel were engaged in a 13-year pursuit of the Apache Chief. Geronimo traveled with his community, including 35 men and 108 women and children, who in the end surrendered in exhaustion and were met with promises that were never fulfilled. It was one of the most expensive and shameful of the Indian Wars… The military, it seems, is comfortable with this ground. Indeed, Native nomenclature in the US military is widespread. From Kiowa, Apache Longbow and Black Hawk helicopters to Tomahawk missiles, the machinery of war has many Native names. (The Huey helicopter―Bell UH-1 is the Iroquois, and the Sikorsky helicopters are also known as Chickasaw, Choctaw and Mohave helicopters.) As the Seventh Cavalry invaded Iraq in 2003 in the “Shock and Awe” campaign that opened the war, one could not help note that this was the name of the cavalry division that had murdered 300 men, women and children at Wounded Knee. Yet, despite our history and the present appropriation of our lands and culture by the military, we have the highest rate of military enlistment of any ethnic group in the United States. We also have the largest number of living veterans out of any community in the country. We have borne a huge burden of post traumatic stress disorder among our veterans, and continue to feel this pain today, compounded by our own unresolved historic grief stemming from colonization. In this book, I consider the scope of our historic and present relationship with the military and discuss economic, ecological and psychological impacts. I then examine the potential for a major transformation from the US military economy that today controls much of Indian Country to a new community-centered model that values our Native cultures and traditions and honors our Mother Earth… -- Take Action Sign the petition and see what else you can do to stop Line 3 and support Water Protectors: https://www.stopline3.org/biden While on the topic of Indigenous issues, there is a renewed campaign to free Native American activist Leonard Peltier from prison. Read about his story and, if you are moved to do so, support the Leonard Peltier Freedom Ride 2021 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source LaDuke, Winona. The Militarization of Indian Country. Michigan University Press, 2012. — Further Resources Honor the Earth: a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues. https://www.honorearth.org/ White Earth Land Recovery Project: reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people. https://www.welrp.org/ Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed