|

(click here to view the original post on Facebook)

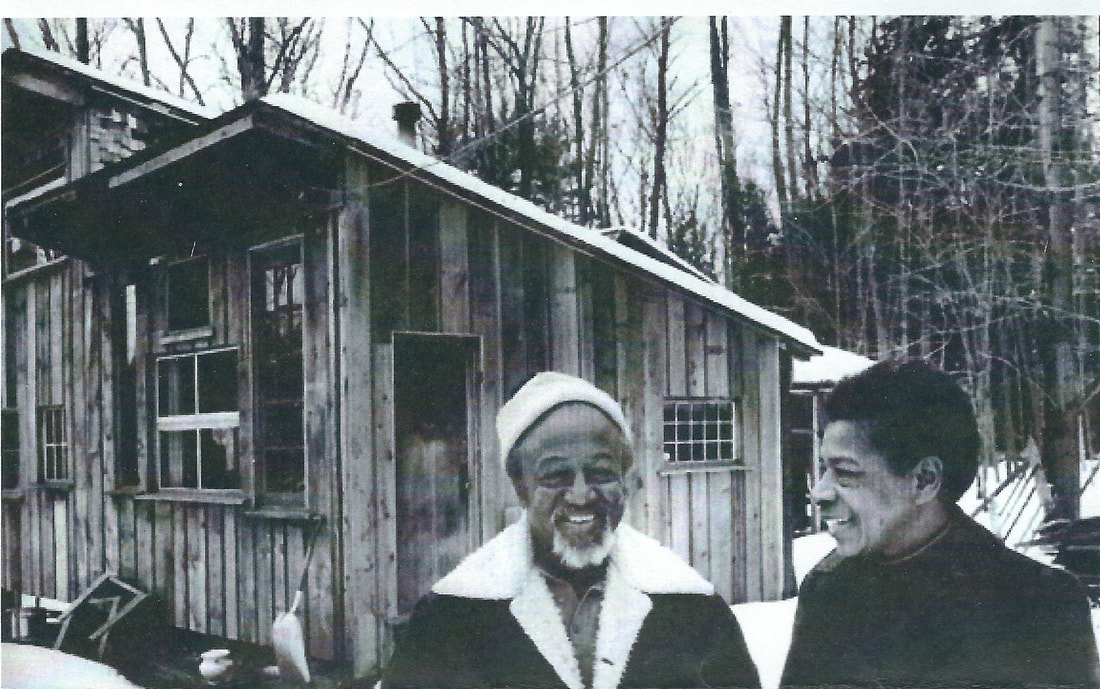

For this week's Peace of History: Let us continue honoring the legacies of Wally and Juanita Nelson. Last week, we surveyed some of the political movements, projects, and actions that carried Wally’s and Juanita’s respective brilliance across the country. This week, we will focus on how they lived as homesteaders in their later years, and how they influenced and inspired so many to live simply, happily, cooperatively, and consistently with pacifist values. We shall read some of the arguments the Nelsons themselves made in defense of their political convictions and their simplified lifestyle, as well as the words of friends, neighbors, and fans of these extraordinary individuals. Wally is quoted as saying: “Nonviolence is the constant awareness of the dignity and humanity of oneself and others; it seeks truth and justice; it renounces violence both in method and in attitude; it is a courageous acceptance of active love and goodwill as the instrument with which to overcome evil and transform both oneself and others. It is the willingness to undergo suffering rather than inflict it. It excludes retaliation and flight.” It is this expansive concept of nonviolence that proved to be a throughline in the lives of Wally and Juanita. In particular, the Nelsons’ belief in the “active love and goodwill as the instrument” for social transformation, as well as their “willingness to undergo suffering rather than inflict it” led to a successful radical rejection of the dominant economic system for decades. As US involvement in the Vietnam War escalated, in 1970, Wally and Juanita moved to Ojo Caliente, New Mexico to learn to be homesteaders. From Juanita’s memorial program: “...Juanita was intent on dissociating herself from an economic system that spawned injustice and war. She saw very clearly the connection between our modern lifestyles and war-making…Wally, who vowed he would never again have a hoe in his hand after the sharecropper days of his youth, needed some convincing. He could see, however, that Juanita’s vision of self-sufficiency was something totally different, and he acquiesced.” They learned to grow and preserve their own foods and live simply, with limited electricity and other “modern” amenities. In 1974, facing affordability issues, the couple relocated to Deerfield, Massachusetts upon the invitation of Randy Kehler and a Quaker-run school at Woolman Hill. There, with the help of old and new neighbors and friends, Juanita and Wally “...took apart and reassembled a cabin, had a well dug, and built an outhouse on the half-acre or so of land that the Woolman Hill community allowed them to use, as specified in a Memorandum of Understanding.” Despite -- or perhaps because of -- their extremely humble lifestyle, Wally and Juanita were known for their happiness and love for their fellow humans. Race had no meaning to them, except to mean the human race. Randy Kehler, long-time friend and neighbor of the Nelsons, said of Wally, “He showed us how to lead a life of integrity and how to have the courage of our convictions. He demonstrated that you can choose to live a different way and achieve a level of happiness most people can’t imagine. He was a very happy man.” And with Juanita, according to Ed Agro, “[E]ach conversation began and ended with hugs and smiles.” But their happiness did not necessarily mean they loved every part of their radical lifestyle. With clarity and humor, Juanita herself made reference to some of the sacrifices they’d had to make to follow what Wally referred to as “rightlivelihood” in a silly popular poem she wrote in New Mexico called “Outhouse Blues”: Well, I went out to the country to live the simple life, Get away from all that concrete and avoid some of that strife, Get off the backs of poor folks, stop supporting Uncle Sam In all that stuff he’s puttin’ down, like bombing Vietnam Oh, but it ain’t easy, ’specially on a chilly night When I beat it to the outhouse with my trusty dim flashlight -- The seat is absolutely frigid, not a BTU of heat… That’s when I think the simple life is not for us elite. Well, I try to grow my own food, competing with the bugs. I even make my own soap and my own ceramic mugs. I figure that the less I buy, the less I compromise With Standard Oil and ITT and those other gouging guys. Oh, but it ain’t easy to leave my cozy bed To make it with my flashlight to that air-conditioned shed When the seat’s so cold it takes away that freedom ecstasy, That’s when I fear the simple life maybe wasn’t meant for me. Well, I cook my food on a wood stove and heat with wood also, Though when my parents left the South I said, “This has got to go,” But I figure that the best way to say all folks are my kin Is try to live so I don’t take nobody’s pound of skin. Oh, but it ain’t easy, when it’s rainy and there’s mud To put on my old bathrobe and walk out in that crud; I look out through the open door and see a distant star And sometimes think this simple life is taking things too far. But then I get to thinkin’, if we’re ever gonna see The end of that old con game the change has got to start with me. Quit wheelin’ and quit dealin’ to be a leader in any band, And it appears the best way is to get back to the land. If I produce my own needs I know what’s goin’ down, I’m not quite so footsy with those Wall Street pimps in town. ’Cause let me tell you something, though it may not be good news, If some folks win you better know somebody’s got to lose. So I guess I’ll have to cast my lot with those who’re optin’ out. And even though on freezing nights I will have my naggin’ doubts, Long as I talk the line I do and spout my way out views I’ll keep on usin’ the outhouse and singin’ the outhouse blues. Inspirations to multiple generations of peace activists, Juanita and Wally were beloved by distant fans and their closest neighbors to the end. After Wally passed away, Juanita suffered a stroke in late 2010, at which point the community they had cultivated took action to take care of her. Let us end with the last part of Juanita’s memorial program: "[Many] opened their homes to Juanita and cared for her as a beloved member of their families for the last four years of her life. Many friends and acquaintances visited and supported her during this time. The love and steadfast commitment that Juanita extended to others during her long life circled back to embrace her: a beautiful ending to an extraordinary, well-lived, remarkable life.” Next week, we will take a look at Ray Robinson, a peace and civil rights activist who disappeared at Pine Ridge Reservation during the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee. “A Celebration of the Remarkable Life of Juanita Morrow Nelson" Long, Tom. “Wallace Nelson, 93, pacifist and early civil rights activist,” The Boston Globe. Nelson, Juanita. “Outhouse Blues” https://nwtrcc.org/juanita-nelson-remembrance-and-apprecia…/ Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed