|

(click here to view the original post on Facebook)

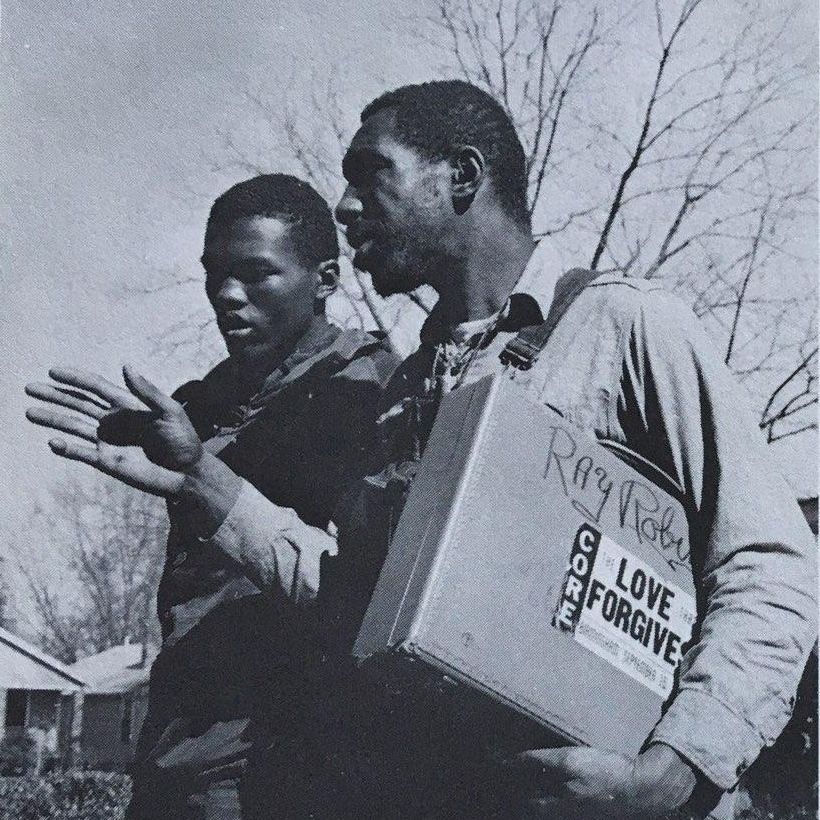

For this week’s Piece of History: We shine a light on the little-known peace and justice activist Ray Robinson. Born in Bogue Chitto, Alabama on September 12, 1937, Ray Robinson was a prize fighter before joining the peace and justice movements. Like Juanita and Wally Nelson, and many other African-Americans involved in the 20th century peace and justice movements, Ray is often characterized as a “civil rights” activist, but his work went well beyond black liberation in America. As his daughter Desiree Mark is quoted: “His whole thing was not black civil rights. It was human civil rights.” Ray attended the 1963 March on Washington, but one could argue that his fully active participation in the movement began later that year when he joined the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace organized by the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA). From Power of the People: “The purpose of the walk was to present to the Cuban people and their leaders the idea of nonviolent resistance and to protest the existence of the US naval base at Guantanamo.” From the beginning, however, the organizers had planned for the Walk to be racially integrated, and had expected to be challenged by citizens and law enforcement as they walked through the segregated South. Thus, the Quebec to Guantanamo Walk demonstrated nonviolent civil disobedience in practice, and promoted peace on the interpersonal, national, and international levels. Although not yet a “tried nonviolent activist” at the time he joined the Walk, Ray’s charisma, forthrightness, and audacity convinced Bradford Lyttle and other organizers to welcome him into the group. Ray was often described as a born leader, one who “put himself out in front of the project.” For example, while the other Walkers themselves were antiracist, many of them were still hesitant to openly challenge segregation in the South until Ray pointed out the hypocrisy of even entertaining the notion: “He wondered who was going to listen to us if we didn’t even feel free, ourselves, to behave naturally with one another” (Deming p. 75). Ray was tall, boisterous, and very visible, which sometimes made him a main target for segregationists. In Griffin, Georgia, after he and his fellow Walkers had been arrested for leafleting in a public park, the local police and a Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) agent used an electric cattle prodder on the walkers’ legs, genitals, spines, chests, and faces. Ray, however, was “particularly brutally tortured,” a pattern that would unfortunately repeat itself. The group was later arrested again in Albany, Georgia. There, Ray and several others went on a hunger strike to protest the conditions of the prison where they were incarcerated. Ray also attempted abstention from water multiple times. Chief Pritchett of the Albany Police Department had had a particular hatred for the Walkers, and especially for Ray Robinson. From Barbara Deming’s Prison Notes: “Ray has obsessed the Chief’s imagination from the start. He has, for one thing, been especially uncooperative -- even flipping himself off the stretcher as he was being carried into jail. Just the fact of his great physical strength and agility has obsessed the Chief, giving him hope of provoking him into using it to our discredit -- especially when he learned that Ray had once been a professional boxer…” (Deming p. 112). Pritchett attempted to break Ray’s fasts and provoke Ray’s aggression by a great range of physical and psychological tortures and threats, from beginning the process to transfer him to a mental asylum, to locking him in a “cell within [a] cell” where he could fit only if he “lay catercorner” (p. 107). There were more than a few times when Ray struggled with his own commitment to nonviolence under the injustice and torment of his incarceration. For example, at one point, Ray broke some shutters and a window in his overcrowded cell, and also pulled the toilet off the floor, in order to get medical attention for a sick but neglected African-American inmate. And yet, as Barbara Deming speculates, “Perhaps the very fact that Ray has to struggle with himself more than most to try to be nonviolent has made him especially real to a man like Pritchett.” Even as the Chief delighted in tormenting his prisoners, he was still known to deliver the handwritten notes that the prisoners would write to each other, including those of Ray. From Deming: “I remind myself, too, of the Chief’s surprising act upon Ray’s return -- when he brought around to my cell some writings Ray wanted me to see. Would he have been moved to such a gesture if, in the course of gaining his “victory” over Ray, Ray had not become for him the opposite of the grotesque stereotype the Chief liked to conjure up for us -- if he had not become for him a real person?” (Deming p. 115-116). Indeed, Ray had written a statement for Barbara Deming regarding the material damage he had caused in the prison, which Barbara then sent to the local paper. The text, more like a prayer than a legal statement, explained his personal growth and inner struggles regarding peace and nonviolence, and was widely circulated. Deming wrote: “I wonder now whether the words published in the Herald could have touched any of the paper’s readers in the white community. It doesn’t seem impossible to me… [An African-American woman Pritchett knew and respected] called him and read Ray’s statement to him over the telephone. Ray had now begun his first water fast… She told me that after she read Ray’s words to the Chief there was simply a long silence at the other end of the line. The Chief could usually find something to say, and it was her guess -- though it could only be a guess -- that he had been shaken.” (p. 114-115). After the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace, Ray continued his involvement in the peace and justice movements, participating in the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi, throwing in his support for Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1967, and helping to organize the Poor People’s Campaign’s Resurrection City at the Washington Mall in 1968, among many other activities. In 1973, while members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the FBI faced off at Wounded Knee at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, over the objections of his wife Cheryl, Ray Robinson traveled up to South Dakota to see what he could do to help reconcile the tense situation. Stories differ over what happened when Ray arrived at Pine Ridge, but most reports agree that he was shot by a Native man over a misunderstanding or what was perceived as insubordination. Anti-black prejudice may have played a factor, and some AIM members made it clear that Ray and other African-Americans were not wanted in “Indian Country.” Nevertheless, it appears that Ray’s last acts were guided by the pacifism and the faith in interracial peace he had begun to develop a decade earlier. Let us leave you this week with Ray’s statement from that Albany jail, that prayer that stunned his tormenter into silence: “Yes I was one of the angry young men, yes I rebel against society. I had no respect for law and order or man, especially the white man the one who has made me feel inferior… The most powerful weapon to me at the time being hatred, disrespect for anyone [white], I never trusted him, and every chance I got, I tried to hurt him… I was violence. I got at one point where I started waiting for one to assault me, where I could strike back with all my strength… I could not fight him legally, and win, so I decided to take up boxing where the world could watch and see me beat one with my hands… Revenge was what I thought I got… So now come a new thing to me that’s called nonviolence and I’m trying it. But yet my past of hatred for him has been stirred up again. Which way shall I go? It’s easy to go back to revenge, and God know I have all the rights… This thing that’s called nonviolence is the biggest challenge I have ever tried as a man and altho it’s hard, I have manage to continue to hold my violence in check. But how much longer can I stay this way? … Maybe more strength on my part will help. But really why should it be on my part, especially since I the oppressed. I’ll just leave things into God’s hands. But here I’m confused about God, where is he now? I need him now. But just when do God put his hand into this thing? … God … can’t you see just what I going thru as a young man? If I sound as tho I’m beginning to doubt you, God, if there’s one, show me your face, don’t keep hiding your face from me, don’t put words into others’ mouths to explain to me about you… But yet God I haven’t thrown you completely out of my mind. So give me strength and courage to continue onward to things unknown, who knows what the tomorrows will bring.” (Deming p. 112-113). Next week: we will tell the story of Bob Moses, an exceptional organizer and activist in the peace and civil rights movements. “A follower of Martin Luther King Jr. might be buried at Wounded Knee.” https://www.indiancountrynews.com/…/887-a-follower-of-marti… Cooney, Robert and Helen Michalowski (ed.). The Power of the People: Active Nonviolence in the United States. Peace Press. Deming, Barbara. Prison Notes. “Flash from Albany.” https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6312_cnva_albany2.pdf “Nonviolence and Police Brutality: A Document.” https://www.crmvet.org/info/quebec_guantanamo.pdf Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed