|

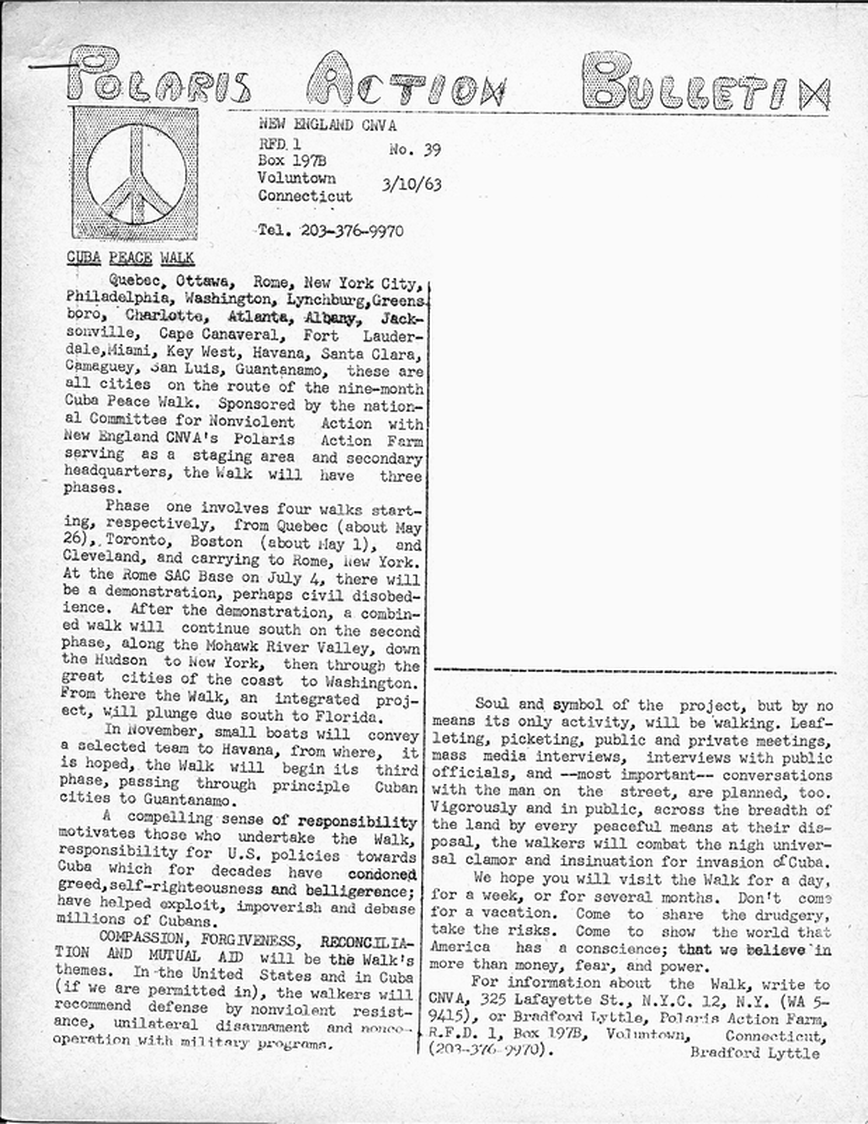

In the summer of 1963, less than a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis and just two years after the failed US invasion of Cuba, the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) organized the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace, a months-long journey down the North American east coast, calling for “compassion, forgiveness, reconciliation and mutual aid” between the United States and Cuba. Peace activists started the walk as far north as Quebec City, converged in Rome, NY, and then walked all the way down to Key West. From there, they planned to take small boats to Cuba itself in order to walk across the great island with the same message. The project was not without its risks. Many of the participants had done similar walks in the recent past — the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace had been completed in 1961, which inspired several shorter walks in the following years. So, many of the participants were prepared for the day-to-day difficulties of walking every day for months straight. Most were also accustomed to the occasional ridicule and hostility that arose in some places — part of the point of walking was to be able to stop and talk to locals at any time. Many had been arrested before and knew what to expect in jail. But on this walk, the activists would also have to contend with violent anti-communist Cuban immigrants as well as Jim Crow. Several activists were arrested in Albany, Georgia for challenging Jim Crow laws, as the walk was always planned to be racially integrated. For some participants, these experiences with such hatred illustrated just how these social justice issues are related to each other. Barbara Deming, New England CNVA member who was jailed at Albany, famously discussed this exact topic in her book Prison Notes. Indeed, several members of the New England CNVA at VPT (then called Polaris Action Farm) served as lead organizers of this project, and the Polaris Action Farm itself played an important role in the logistics. Intending to kick off at the end of May 1963, organizing efforts began several months earlier. In fact, the whole length of the walk actually started as three separate walks organized by regional groups — the New England CNVA’s newsletter Polaris Action Bulletin was promoting the walk to Rome, NY as far back as December 1962. But within the first couple of months of the new year, the regional groups had stitched the three routes together to form one of the biggest US peace actions of the early 1960s. On Monday, January 23, we will celebrate the 2nd anniversary of the international prohibition of nuclear weapons — an amazing international achievement that undoubtedly owes much to the efforts of those 1960s peace activists. To join us or to learn more, see the event page here: https://fb.me/e/2frWLbKeX Moreover, we at VPT are already starting to plan some summer events, including the arrival of the Golden Rule in New London, CT in July. Coincidentally, the Golden Rule just left Cuba a few days ago. As the world’s first modern protest ship and a vessel originally operated by the CNVA, the Golden Rule has strong historical ties to VPT. We at VPT will put on some public events related to the ship in the months before it arrives as well as when the ship is here. To stay in the loop about these events, sign up for our newsletter: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 —

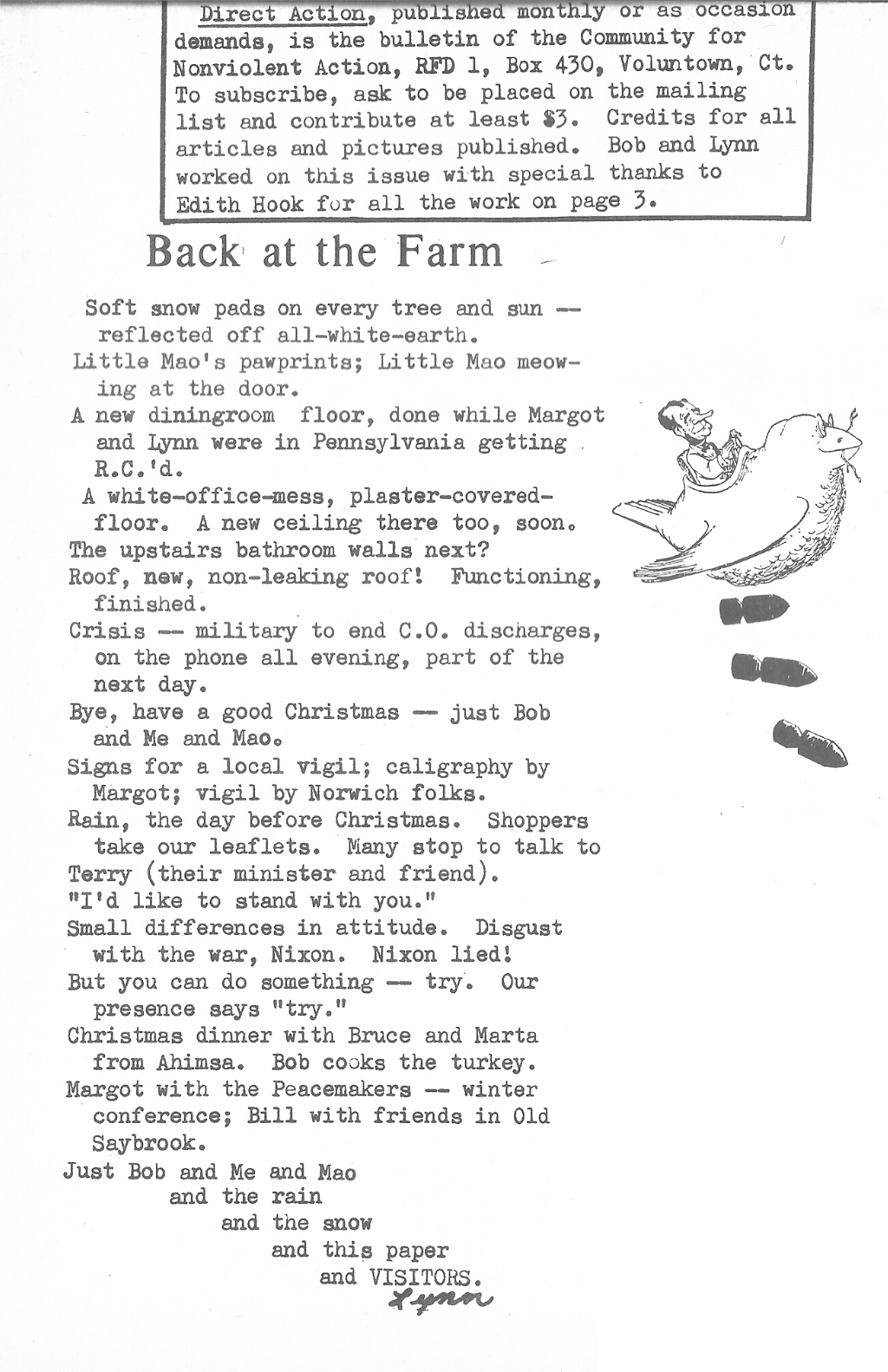

Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source Lyttle, Bradford. “Cuba Peace Walk.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 3 March 1963 (Bulletin #39), page 1. For many, the end of the year is the time for being sociable, visiting friends and family, living in the present — but it’s also time for quiet reflection and planning for the future. This is as true for the activist as it is for the average person. At the end of 1972, a CNVA member living at VPT penned the following poem that expresses much of this balance between introspection and sociality — reflecting on the organization’s recent accomplishments and next steps to complete; on the tranquil solitude of VPT in wintertime interspersed with flurries of guests and activities; on the deep and wide connections this little group of antiwar activists had made in their area and across the country over the last decade; and on the ways in which these people formed genuine relationships and communities within and apart from the work. As the winter blues start up, it helps to remember that even a small group in sleepy old Voluntown can become a critical part of a mass movement. Happy a safe and happy new year. -- —

Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source Lynn. “Back at the Farm.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 30 December 1972 (Bulletin #129), page 4. “Christmas Week Training and Study Course in Nonviolent Direct Action and Peace Education” (1961)12/24/2022

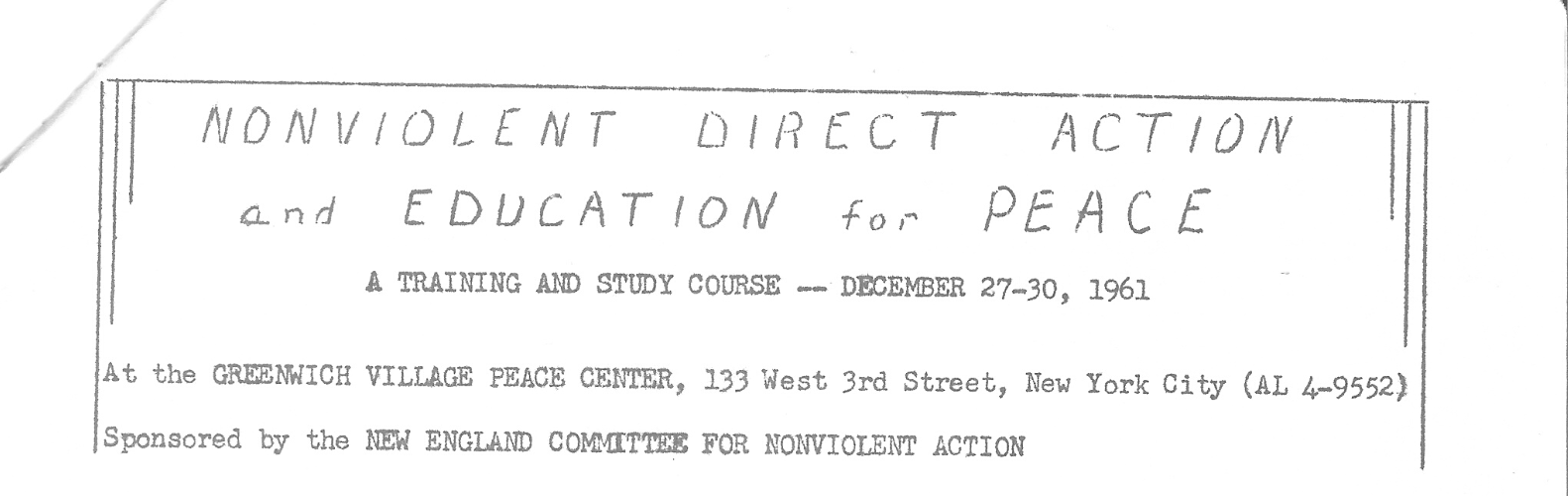

For many, Christmas means taking time off from work and relaxing. For others, it’s all about spending time with family. But for Connecticut peace activists of the 1960s — perhaps inspired by the radical nonviolent resistance of Christ himself — Christmas was time for training. During the week after Christmas in 1961, the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action sponsored a four-day training and study course in New York City to teach their tactics and skills. This training course, and others like it, were responsible for spreading many of the protest methods and philosophies that the era has become known for. As shown in the “Tentative Schedule,” the organizers of the training were concerned not just with how one should protest, but also with why one should protest in certain ways — namely, nonviolently and with direct action. Much of the time would also be spent on learning and developing practical skills, such as writing leaflets and press releases. Moreover, the whole curriculum included multiple moments to reflect on recent history, current events, and both global and local issues. In fact, an early version of the “think global, act local” ethos can be seen in the CNVA’s organizing model: a mostly decentralized organization of mutually supportive locally- and regionally-based groups — all connected by newsletters, speaking tours, actions, and trainings like this one. Finally, the 1961 “Christmas Week Training” would end with an opportunity to apply some of what the participants had learned — out on the streets of New York. These activists of decades past show us that there is no shortage of opportunities to spin the conversation to the topic of peace and disarmament — and that many of our society’s traditional practices and values contradict our government’s eagerness for war. -- —

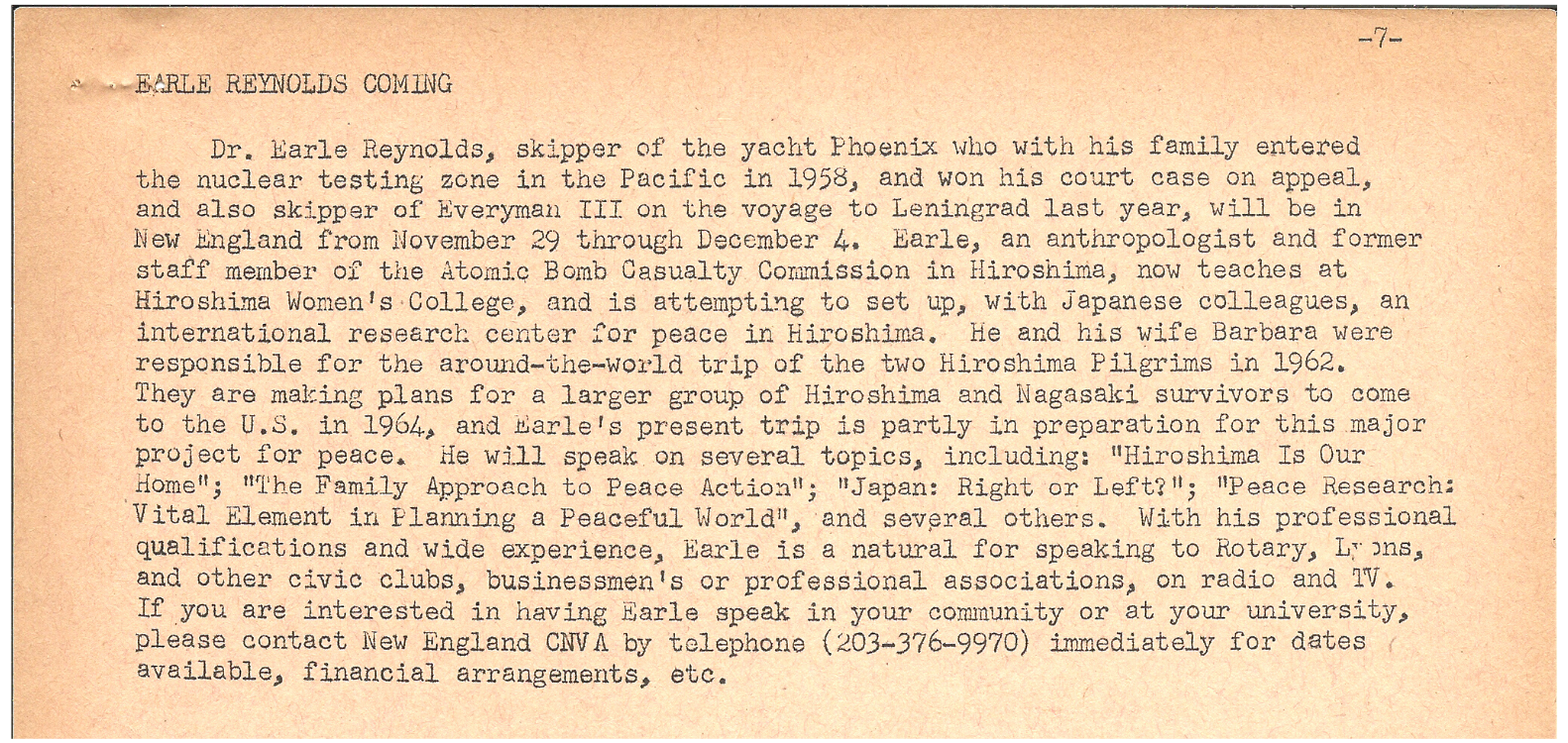

Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “Christmas Week Training and Study Course in Nonviolent Direct Action and Peace Education.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 16 December 1961 (Bulletin #29), pages 3-4. Near the end of the year 1963, the renowned Dr. Earle Reynolds visited New England as part of a speaking tour. Dr. Reynolds had joined the antiwar movement in dramatic fashion and became something of an activist celebrity years earlier in 1958: by sailing with his family (and one Hiroshima citizen) into the US Pacific Proving Grounds in protest of the nuclear weapons his government had been testing there for years. From then on, Earle Reynolds committed himself completely to resisting war and especially nuclear weapons. As a lead researcher for the US Atomic Energy Commission in Hiroshima from 1951 to 1954, Dr. Reynolds became one of the world’s foremost experts on the effects of radiation. Coming to understand the horrors of nuclear weapons better than almost anyone, Dr. Reynolds was so disturbed by what he had found in his research that he abandoned the rest of the study in 1954. Four years later, in the middle of a family sailing trip around the world, the Reynolds family met the crew of the CNVA’s Golden Rule ketch and together decided to carry out the Golden Rule’s mission in its stead: to disrupt the nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific by physically entering the restricted zone. (Read our story on the Reynolds' forbidden voyage here) For the next several years, Dr. Reynolds was prominently involved in a number of high-profile actions against nuclear weapons. He sailed to the Soviet Union twice to protest their participation in the nuclear arms race: the first time again with his family in 1961, the second time as the skipper of the CNVA ship Everyman III in 1962. Back to 1963, Dr. Reynolds would come to share his activist experiences and scientific expertise with some of his most ardent supporters — the premier antiwar group in the 1960s northeast, an organization that came out of the one that sent the Golden Rule to the Pacific in the first place, as well as VPT’s predecessor: the New England Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA). Earle Reynolds, as well as his first wife Barbara, continued antiwar activism for the rest of their lives. Earle would go on to conduct more sail-based antiwar and humanitarian missions, including multiple trips to Vietnam during the American occupation. Barbara’s activist career was arguably even more impressive and deserves its own post at a later date. And while the Golden Rule was not able to complete its first mission, the ketch dutifully served in many more successive actions in the antiwar movement before eventually being scuttled. Years later, Veterans for Peace recovered and restored the ship in order to both preserve its history and continue its function as a protest ship. With a new crew from Veterans for Peace, the restored Golden Rule is currently sailing around the United States to spread its antiwar message. VPT is getting ready to welcome the historic ship when it visits New London in June 2023. See below for the original announcement of Dr. Reynolds’ New England CNVA visit from 1963. And watch this page for updates on events leading up to the Golden Rule’s arrival in New London! -- —

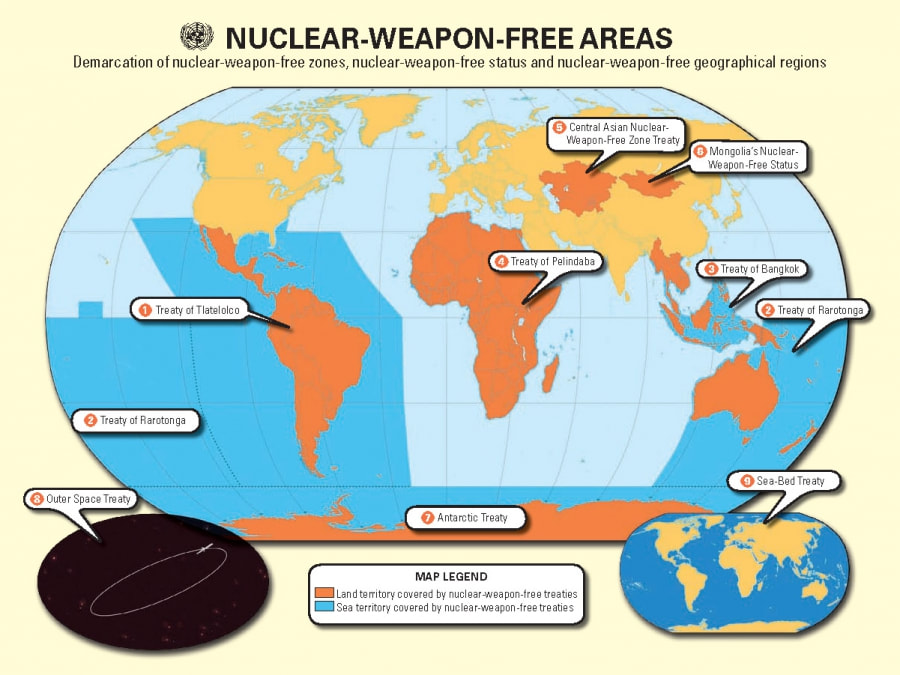

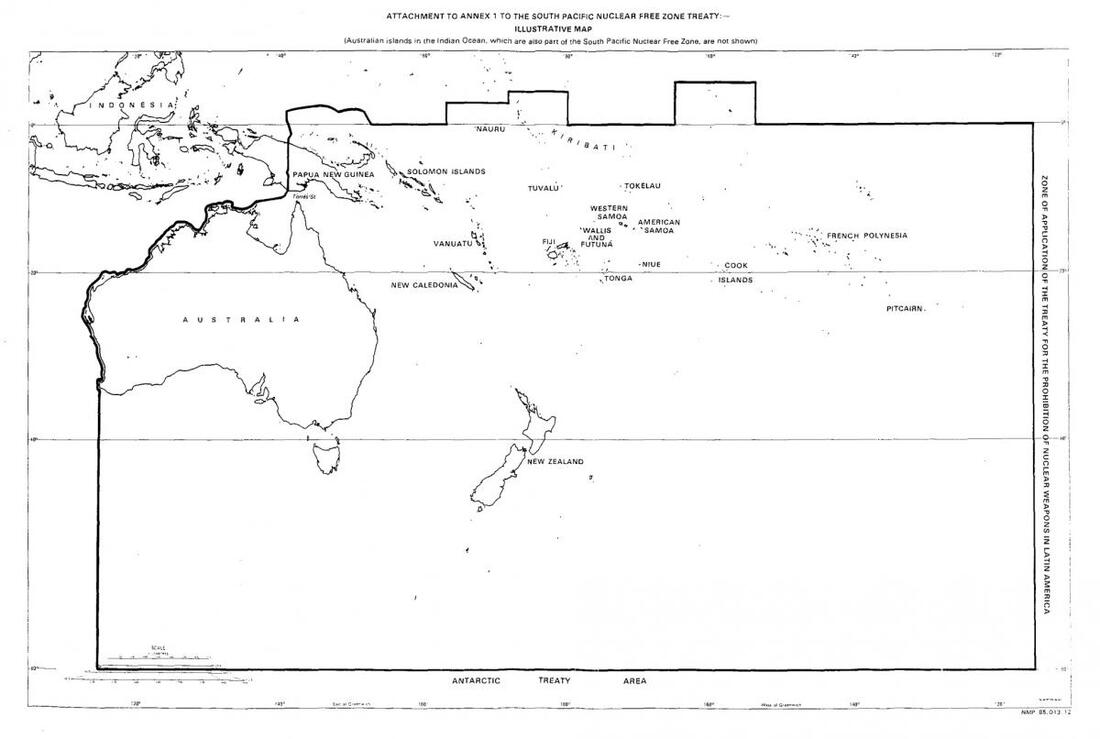

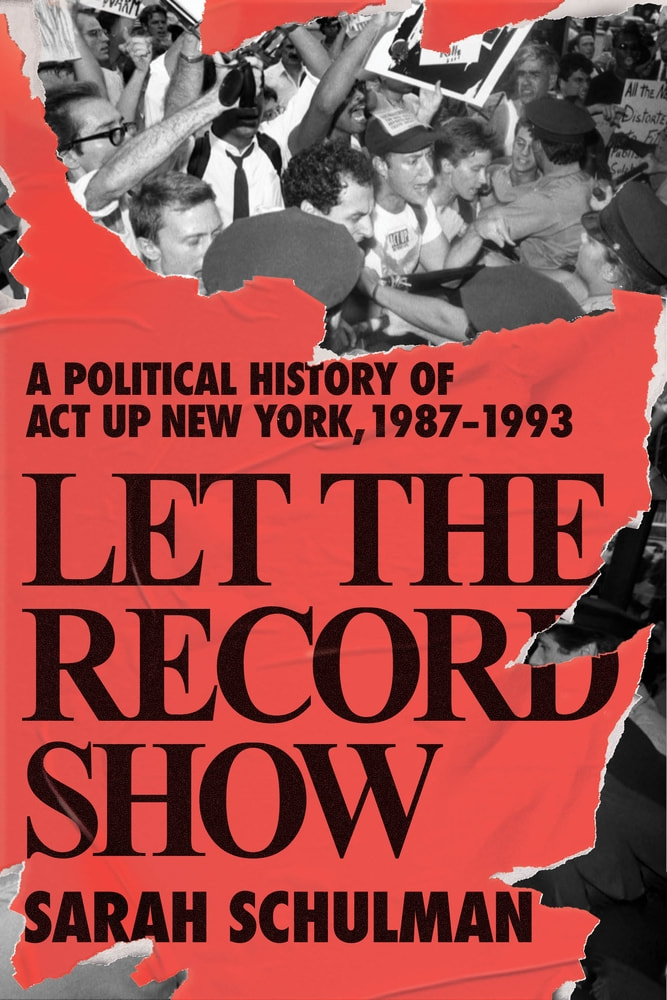

Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “Earle Reynolds Coming.” Polaris Action Bulletin. 28 October 1963 (Bulletin #46), page 7. December 11 is the anniversary of the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty coming into force in 1986 — one of eight international treaties which have banned the development, manufacture, control, possession, testing, stationing or transporting of nuclear weapons across large swaths of the planet. In fact, today, almost all of the sovereign governments in the southern hemisphere have forged regional nuclear-weapon-free zones, with some of these zones reaching up past the equator: all of South America, Central America, and the Caribbean (1968), the Pacific states (1986), and southeast Asia (1997). Central Asia (2009) is well into the northern hemisphere. And all of Africa, the second largest continent on Earth, is a nuclear-weapon-free zone (2009). In addition, Antarctica (1961), outer space (1967), and the seabed (1972) are internationally recognized nuclear-weapon-free zones. These treaties are recognized not just by the party nations, but also by the United Nations as well as the world’s officially acknowledged nuclear weapons states. Most of these treaties are decades old. Sometimes, in the United States, it feels like real change will never come. Opposition to war and promotion of voluntary national disarmament have been some of the most difficult issues for American activists. These demands may seem unrealistic to some, even to other activists. But if we look elsewhere in the world, we find large coalitions of national governments that have done exactly that — some long ago and others quite recently — and spurred on by popular movements of their own citizens. In the words of Nelson Mandela: “It always seems impossible until it’s done.” Below, we share an excerpt from an article on the topic by Lawrence Wittner, history professor at SUNY Albany. In the excerpt, Wittner provides an excellent overview of how determined local activists were able to grow their movements with domestic and international support, and how these movements successfully defied the nuclear weapons states (especially the United States) and convinced their own governments to reject nuclear weapons forever. The link to the full article can be found at the end of this post. -- Although the worldwide campaign against nuclear weapons was in the doldrums during the early 1970s, the antinuclear movement maintained a lively presence in the Pacific, largely in response to nuclear testing in that region. Spurning the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the French government continued atmospheric nuclear testing on Moruroa in the South Pacific, sending deadly radioactive clouds drifting across Pacific island nations. In response, New Zealand activists began defying the French government during 1972 by sailing small vessels into the test zone. Joining the fray, the New Zealand Federation of Labour pledged a strict ban on French goods and the Labour Party took a principled stand against continued nuclear testing, leading to its election victory that November. In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney; scientists issued statements demanding an end to the tests; unions refused to load French ships, service French planes, or carry French mail; and consumers boycotted French products. In Fiji, activists formed an Against Testing on Moruroa organization, which, in 1974, began planning a regional antinuclear conference. Nuclear testing in the Pacific also triggered the establishment of Greenpeace. In 1971, Jim Bohlen and Irving Stowe, two antiwar Americans who had relocated to Vancouver, Canada during the Vietnam War, decided to sail a ship north to Amchitka Island, off Alaska to protest U.S. government plans to explode nuclear weapons there. En route, the crew read of a Cree grandmother's 200-year-old prophecy that there would come a time when all the races of the world would unite as Rainbow Warriors, going forth to end the destruction of the earth. Deeply moved, the crew enlisted in that cause. Although U.S. authorities arrested the crew members as they approached the nuclear test site, thousands of cheering supporters lined the docks in Vancouver upon their return. Bohlen and Stowe embarked on another voyage to Amchitka and, although they failed to reach it before the U.S. government exploded its nuclear bomb, a new movement had been born. In New Zealand, a former Canadian, David McTaggart, convinced Canada's Greenpeace group that he should sail his yacht into France's nuclear testing zone around Moruroa. When he arrived with a crew in June 1972, a French minesweeper, at the order of the French government, rammed and crippled the ship. But McTaggart returned with a new ship and crew the following year.[...] During the early 1980s, as hawkish governments in the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, and elsewhere renewed the Cold War and threatened nuclear annihilation, the movement reached high tide.[...] Australia, like its counterparts elsewhere, experienced a phenomenal growth of nuclear disarmament activism. Antinuclear professional organizations sprang up, and hundreds of small, local antinuclear organizations appeared. Religious groups backed the campaign, as did women's groups, which established peace camps outside U.S. military bases and, in one case, staged a nonviolent invasion of a U.S. base and tore down its gates. Although the newly formed People for Nuclear Disarmament sought to coordinate activities at the state level and the Australian Coalition for Disarmament and Peace at the national one, the movement usually lacked central direction. Even so, the few united events illustrated its unprecedented popularity. On Palm Sunday 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians took to the streets for antinuclear rallies in the nation's biggest cities. Growing year by year, the rallies drew 350,000 participants in 1985. For the most part, the movement focused on abolishing nuclear weapons, halting Australia's uranium mining and exports, removing foreign military bases from Australia's soil, and creating a nuclear-free Pacific. Surveys found that about half of Australians opposed uranium mining and exporting, as well as the visits of U.S. nuclear warships, that 72 percent thought the use of nuclear weapons could never be justified, and that 80 percent favored building a nuclear-free world. In neighboring New Zealand, the movement attained even greater popularity. Older organizations like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament were reinvigorated, while hundreds of newer ones were formed, including a crop of professional groups. Union, church, and Maori organizations joined the antinuclear campaign. In May 1983, 25,000 women participated in an antinuclear rally in Auckland—the largest public gathering of women in New Zealand's history. Continuing their program of resistance, Peace Squadrons sought to prevent visiting U.S. nuclear warships from entering their nation's harbors. In June 1982, when a U.S. cruiser tried to enter Wellington, maritime workers and seamen closed the port for three days through work stoppages, and 15,000 other workers halted labor for two hours to hold protest meetings. In August 1983, 50,000 people turned out for an anti-warship protest in Auckland. Meanwhile, a Nuclear Free Zone Committee pressed to have local governments proclaim their jurisdictions nuclear free. As a result, by 1984, 65 percent of New Zealanders lived in nuclear-free zones. The New Zealand struggle reached a critical point during 1984-85. With the governing National Party (the conservatives) barely able to sustain an effective parliamentary majority against antinuclear resolutions, the prime minister scheduled an election for July 1984. Assuming that a warships ban (and the necessary revision of the Australia-New Zealand-United States alliance) would be unpopular, the Nationalists made the Labour party's antinuclear policy the centerpiece of their campaign. In turn, Labour and two minor parties spoke out vigorously for a nuclear-free New Zealand. On election day, 63 percent of the voters cast their ballots for the three antinuclear parties, catapulting Labour into power. Taking office as prime minister, David Lange announced a four-part program. It included barring nuclear weapons from New Zealand, halting French nuclear testing in the Pacific, blocking nuclear waste dumping in that ocean, and establishing the South Pacific as a nuclear-free zone. When the U.S. government requested entry for a nuclear-capable destroyer, Lange announced in January 1985 that the warship was banned from his country. Although U.S. officials and the opposition Nationalists bitterly condemned this action, it proved enormously popular. Between 1978 and early 1984, polls found that opposition to allowing nuclear armed ships into New Zealand's ports rose from 32 to 57 percent. And once Lange defied the United States, opposition soared to 76 percent. New Zealand had become a nuclear-free nation—and was proud of it. Protest was rising elsewhere in Asia, as well. In the Philippines, the building of a giant nuclear power plant inspired growing opposition, as did U.S. military bases at Subic Bay and Clark Field, which housed nuclear-armed planes and warships. With the government's nominal lifting of martial law in 1981, representatives of church, labor, women's, student, and other groups organized the Nuclear Free Philippines Coalition, dedicated to halting construction of the power plant and closing down U.S. military bases. By early 1983, it claimed the support of 82 organizations. In South Korea, the presence of large numbers of U.S. nuclear weapons and the frightening promises of U.S. officials to employ them in a future war led to a growing public fear of nuclear disaster and protests by church groups. Furthermore, in India, a newly-formed Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy issued numerous public statements by prominent citizens warning against the activities of their nation's "nuclear bomb lobby" and pressed the government to reject nuclear weapons. The antinuclear struggle reached a crescendo in the scattered island nations of the Pacific. Decades of western use of the region for thermonuclear explosions, nuclear missile tests, and nuclear warship ports, topped off by the latest great power nuclear confrontation, led to a surge of resistance among native peoples. In Fiji, church, union, and student organizations established the Fiji Anti-Nuclear Group to work for the creation of a nuclear-free Pacific. In Tahiti, thousands of people marched through the streets protesting French nuclear tests and demanding independence from France. On Kwajalein atoll, some 1,000 Marshall Islanders—reacting to a U.S. government plan to extend its military rights by fifty years—escaped their crowded squalor on Ebeye Island by staging "Operation Homecoming," an illegal occupation of eleven islands they had left years before to accommodate U.S. nuclear missile tests. In Palau, the U.S. government, stymied by that nation's antinuclear constitution, sponsored new referenda to overturn its antinuclear provision. When the third and fourth referenda proved unsuccessful, U.S. officials waged a $500,000 campaign to sway the nation's 7,000 voters in a fifth referendum. But the people of Palau stubbornly voted yet again to keep their islands nuclear free. Deeply resenting their mistreatment by the nuclear powers, delegates to the 1983 Nuclear Free Pacific conference renamed their organization the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement. By 1985, it had 185 constituent organizations. In response to this tidal wave of protest, public policy changed dramatically in the Pacific. In New Zealand, the new Labour government of Prime Minister Lange not only defied Washington by barring nuclear-armed warships, but became a leading proponent of a comprehensive test ban treaty and of a South Pacific nuclear weapons-free zone. In Australia, after the victory of the Labor Party in the 1983 elections, the new prime minister, Bob Hawke, appointed Australia's first minister for disarmament, instructed Australia's representative at the United Nations to support a Nuclear Freeze resolution, withdrew his earlier offer to have Australia test the MX missile, and made his country into a key force in world efforts to secure a comprehensive test ban treaty. Moreover, New Zealand and Australia joined the other eleven nations of the South Pacific in negotiating the Treaty of Rarotonga, designed to prohibit the testing, production, acquisition, or stationing of nuclear weapons in the region. Although nations lacking antinuclear movements, such as China and Pakistan, made progress on their nuclear weapons programs during these years, the Japanese government—beset by waves of protest—proved more cautious, and Japan's "three non-nuclear principles" remained officially enshrined.[...] — Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Lawrence S. Wittner, “Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009. https://apjjf.org/-Lawrence-S.-Wittner/3179/article.html — Further Reading Maharaj, Grace. “The Pacific nuclear legacy belongs to climate change activism” Griffith University: Asian Insights, 13 August 2020. https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiainsights/the-pacific-nuclear-legacy-belongs-to-climate-change-activism/ “Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones” United Nations: Office of Disarmament Affairs, accessed 7 December 2022. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/nwfz/ In observance of World AIDS Day, here we have two excerpts about Jamie Bauer: a member of ACT UP who directly helped shape the organization. Jamie brought the protest tactic of nonviolent civil disobedience to ACT UP, training members who went on to train even more — rippling out to an enormous scale. According to many within the movement, it was nonviolent civil disobedience which largely made ACT UP so successful. Jamie Bauer had been influenced by Barbara Deming, a feminist lesbian activist and writer who had been involved in the antiwar group the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA), which founded the original Voluntown Peace Trust. Jamie was also active with the Women’s Pentagon Action, which was supported by the War Resisters League (WRL). Because of that connection, Jamie knew WRL staff member David McReynolds, and the two ran a training that influenced ACT UP to use nonviolent tactics. David McReynolds also worked with Barbara Deming in both CNVA and WRL (learn more from Martin Duberman’s book A Saving Remnant: the Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds). By the time Jamie Bauer was getting involved with ACT UP, the CNVA had merged into WRL. The closer one looks, the more direct connections one can see between ACT UP, the antiwar movement, the civil rights movement, and many more of the time. In 2020, T: The New York Times Style Magazine interviewed 12 veteran activists of ACT UP to tell their experiences in the organization in their own words. Jamie Bauer was one of the members interviewed, and we have shared their words below. In 2021, a book was published about this period: Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman. Chapter 16 of the book is about the role of civil disobedience in ACT UP, and Jamie Bauer is a central figure throughout. Below, we share excerpts from the beginning of the chapter (find the source link at the end of this post to find your own copy and read the whole story for yourself). --

From “12 People on Joining ACT UP: ‘I Went to That First Meeting and Never Left’” in T: The New York Times Style Magazine JAMIE BAUER, 61 Joined in 1987 In 1981, I became active in the Women’s Pentagon Action, which is a feminist, anti-militarist group with connections to the War Resisters League (WRL), one of the oldest pacifist organizations in the United States. I was trained in nonviolent civil disobedience: We would discuss a demonstration and really walk through the safety of it to make sure that we weren’t doing anything to intentionally hurt people. When ACT UP started in 1987, some of the organizers of the first meeting reached out to the WRL. David McReynolds, a longtime member, and I dispatched WRL members who understood nonviolent civil disobedience — and that included the two of us, both queer — to go to the ACT UP meeting and do a brief training. After that, I just stuck with it. As a pacifist, for me, it was always about acknowledging your anger and channeling it into something productive — and, of course, with people dying, there was so much anger. Although ACT UP did not take a vow of nonviolence, we had a series of principles that were built upon that; we had very clearly drawn lines. For me, the biggest struggle was working with people to make sure that we didn’t overstep those boundaries, that we didn’t turn into the Weathermen [the ’60s and ’70s-era radical faction of the left-wing Students for a Democratic Society], that we didn’t bomb buildings — which, in a time of desperation, when you’re watching all your friends die, would have been an easy direction for us to go in. -- From Chapter 16: The Culture and Subculture of Civil Disobedience in Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman The most influential cohering experience in values inside ACT UP that almost everyone shared was civil disobedience training, and thousands of people experienced it together. Although based in an applied practice with tips and guidelines, all of the instructions were rooted in a very articulate and deep ethical belief system about community. The trainers became a moral center of this culture, profoundly influential on the movement as a whole, and specifically consequential on the individuals who shared this preparation and subsequent experience of nonviolent defiance. JAMIE BAUER Jamie Bauer grew up in Stuyvesant Town, in Manhattan. Their father was a salesman, and their mother was a homemaker. After Hunter High School they went to MIT to study civil engineering, architecture, and urban planning, and earned a master’s in transportation, which had a one-in-eight women-to-men ratio. Jamie found the program to be not very intellectual. “Rigorous, but not very interesting.” Although there was a small gay student union at the school, it was all men. On the other hand, MIT was in Boston, which had a huge lesbian community. And so Jamie came out pretty quickly and start making some connections into the mixed gay movement and into the lesbian movement, the two of which were still somewhat separate at that point. In 1981, they returned to New York to work for the MTA, eventually as director of subway schedules. About two decades after their time in ACT UP, Jamie started to live as nonbinary. In the early 1980s, Jamie had heard a lot about the Women’s Pentagon Action, a mobilization to create a large women’s peace action directly confronting the Pentagon. They went to a couple of meetings and got hooked, “because these women were so interesting and so smart and creative, and knew so much. And I just thought—Well I’m just going to sit here and hang out and absorb this.” Jamie worked with Grace Paley, Vera Williams, Eva Kollisch, Donna Gould, Sharon Kleinbaum, Toni Fitzpatrick, Laura Flanders, Harriet Hirschorn, and other women peace activists. The group came together to make the connections between war, the patriarchy, women’s oppression, the military–industrial complex. It was also an antinationalism group. They did not believe in borders, flags, or patriotism, and believed that women bonding together with other women could save the world. And at that time, 60 to 75 percent of the group were lesbians, but that fact was not acknowledged. “It wasn’t part of the dogma of the group. We were women—which I found a little hard to stomach, because it was so clear that so many [of the] women were lesbians anyway, but they didn’t want it to be a lesbian group.” Jamie learned a lot about organizing, dealing with the police, insisting on the right to take space, and just everything about doing politics on the street.[...] Influenced by the writings of Barbara Deming, Jamie picked up the concept that people have a right to free speech and freedom of assembly and should not have to ask permission for it. And if the state wanted to arrest us for it, that was their business, but the people were not going to ask the state’s permission. So it was nonviolent civil disobedience rooted in an insistence on people protecting their rights by using them, and not letting the government take those rights. When they first came to ACT UP, Jamie found it all very exciting. People were so charged up and just wanted to demonstrate, demonstrate, demonstrate. ACT UP would schedule five demonstrations in a week, and then the members would go to all of them. But Jamie found that they didn’t know anything about demonstrating. For example, at the first Wall Street demo, ACT UP gave the police a list of the seventeen people who were going to be arrested, and each person who was going to be arrested wore an armband so that the police wouldn’t accidentally take the wrong person. Jamie felt that this was overly orchestrated and made it impossible for anybody else to try to jump in. Jamie called this “Celebrity CD [civil disobedience]. They didn’t want three hundred people, at that point, necessarily doing CD. They wanted a couple of name people, with recognition so that would be what would be in the press.” Jamie understood that ACT UP was trying to figure out how to use its anger, because it was a group with a tremendous amount of rage and anger at the system. Although New York City was the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic, the federal decision-makers were in Washington. It was very frustrating to go out into the streets of New York and demonstrate, because they were demonstrating against buildings that people in power weren’t necessarily in. For Jamie, civil disobedience is an American tactic that people understand, in some ways. But Jamie had a particular commitment to a concept of safety. There were people who didn’t understand issues of public safety, personal safety, the safety of the community, or taking responsibility for one’s actions. Jamie and the other trainers really began to talk about civil disobedience as a safe tactic for making a stronger, direct, personal statement, and as a way of getting media attention. They tried to get everybody in the group trained for civil disobedience, because no one always knows when it’s going to happen, or when they’re going to want to do it. When dealing with the police, no organizers can guarantee people’s safety; there are a lot of things that can make it physically safer than just haphazardly running out into the street.[...] — Take Action Join our mailing list for more nonviolent resistance history, local antiwar protests and events, and other opportunities for learning and building community: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. Macmillan: 2021. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374185138/lettherecordshow Turner, Kyle. “12 People on Joining ACT UP: ‘I Went to That First Meeting and Never Left’”. T: The New York Times Style Magazine, published 13 April 2020 (updated 17 April 2020). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/t-magazine/act-up-members.html — Further Reading Duberman, Martin. A Saving Remnant: the Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds. The New Press: 2012. https://thenewpress.com/books/saving-remnant Native American rights and history have been a concern for the Peace Trust for decades; the 1990s campaign to remove the John Mason statue in downtown Mystic is a prime example (see the story here). But it was only a few years ago that we learned that part of our organization’s name — the “Voluntown” of the Voluntown Peace Trust — was a reference to lands conquered from local Native communities and granted to colonial volunteer soldiers in the so-called King Philip’s War (aka Metacom’s War).

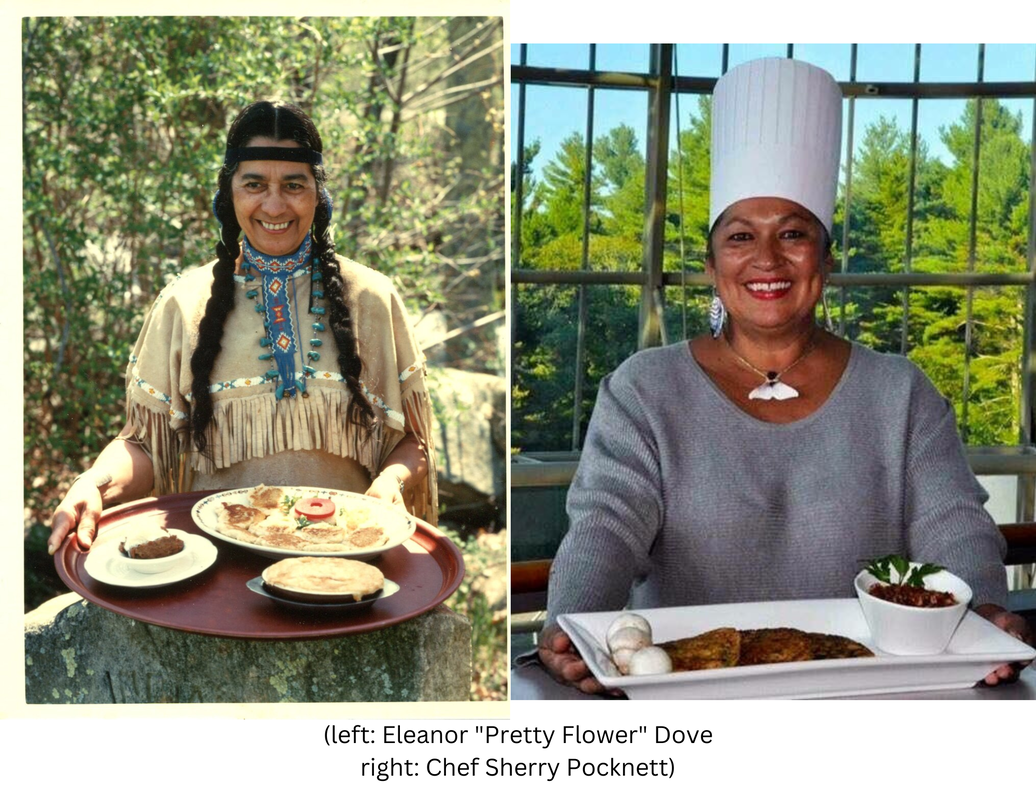

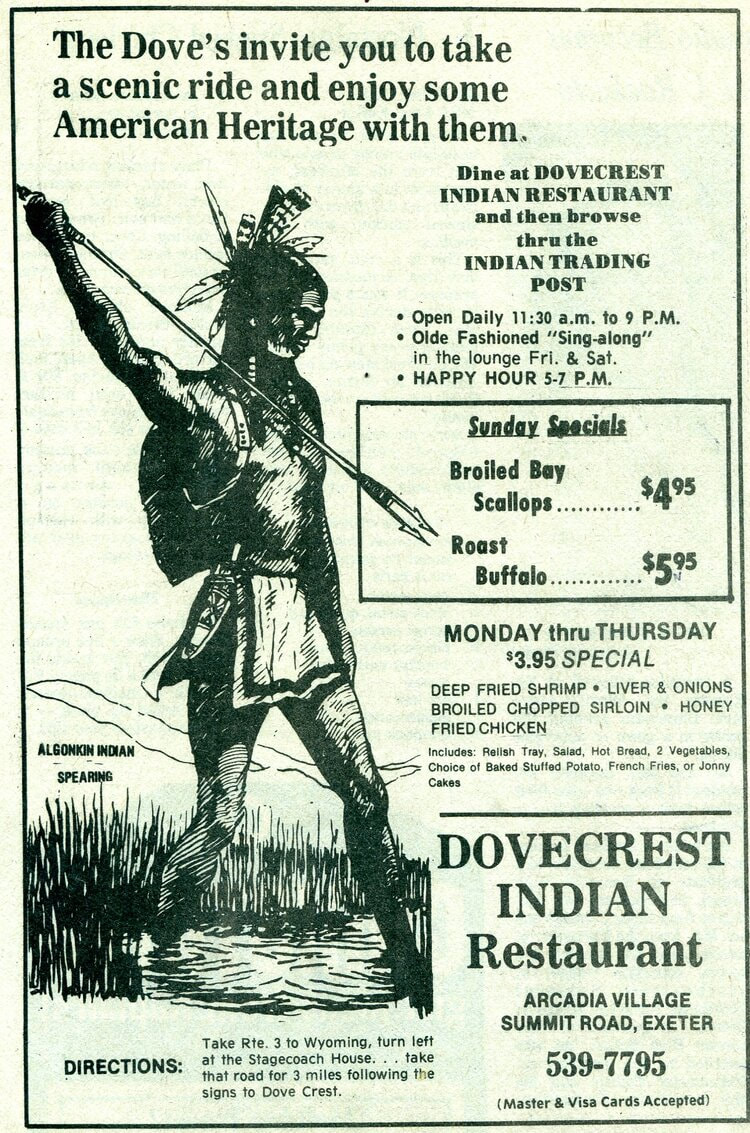

While the war was technically started by a coalition of Native groups led by Wampanoag leader Metacom, it was provoked by years of English aggressive expansion, assertions of dominance, and violations of treaties. In the end, the English colonists turned the conflict into a war of extermination, killing so many Wampanoag and Narragansett peoples that the two formerly powerful nations have not fully recovered to this day. The following is an account of Wampanoag history by Wamsutta (aka Frank James), Wampanoag leader in 1970. Shortly after the Commonwealth of Massachusetts denied his speech and returned to him a whitewashed version, Wamsutta founded the United American Indians of New England and declared Thanksgiving day a National Day of Mourning for Native Americans. This speech became a foundational text for the group, and remains a powerful retelling of the regional history through the Wampanoag perspective. As part of our efforts to learn more about local Native history, spread that historical understanding, and uplift Native voices, we again present “The Suppressed Speech of Wamsutta.” -- “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG” To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970 ABOUT THE DOCUMENT: Three hundred fifty years after the Pilgrims began their invasion of the land of the Wampanoag, their "American" descendants planned an anniversary celebration. Still clinging to the white schoolbook myth of friendly relations between their forefathers and the Wampanoag, the anniversary planners thought it would be nice to have an Indian make an appreciative and complimentary speech at their state dinner. Frank James was asked to speak at the celebration. He accepted. The planners, however, asked to see his speech in advance of the occasion, and it turned out that Frank James' views — based on history rather than mythology — were not what the Pilgrims' descendants wanted to hear. Frank James refused to deliver a speech written by a public relations person. Frank James did not speak at the anniversary celebration. If he had spoken, this is what he would have said: I speak to you as a man -- a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction ("You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!"). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so. It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt's Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people. What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called "savages." Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other "witch." And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the "savage" and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again. The white man used the Indian's nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman -- but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we Indians have been termed "low man on the totem pole." Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons. What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as "civilized" people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags'] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty. History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood. The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his "savageness" has boomeranged and isn't a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian's temperament! High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians! Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently. Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting We're standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us. We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail. You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian. There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We're being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours. Wamsutta September 10, 1970 — Take Action See how you can support the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative: http://www.narragansettfoodsovereignty.org/ Donate to the Sly Fox Den project here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/sly-fox-den-restaurant-and-bar Join our mailing list for announcements of upcoming events on Native history: http://eepurl.com/Oqf99 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Source James, Wamsutta (Frank B.). “THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG.” United American Indians of New England. http://www.uaine.org/suppressed_speech.htm — Further Resources Here is a podcast episode for all ages about Wampanoag and Narragansett thanksgiving traditions featuring Loren M. Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum: “Giving Thanks!” Time For Lunch podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/giving-thanks/id1504928110?i=1000499993371 From 1963 to 1984, there was a Native American restaurant called Dovecrest in Exeter, Rhode Island. The place was founded by Eleanor (Pretty Flower, 1918-2019) and Ferris Babcock Dove (Chief Roaring Bull, 1915-1983), both members of the Narragansett-Niantic Tribal Nation. The eatery originally served “standard steakhouse fare,” but eventually some patrons started asking to try the traditional Indigenous food the family ate in the back. Soon, Indigenous cuisine was featured on the Dovecrest menu. But to call Dovecrest just a restaurant would be inaccurate — it was so much more than that. It was a meeting place and cultural center for many Narragansett-Niantic people in the area. It was an educational facility to spread knowledge of Narragansett-Niantic traditions, cultural practices, and of course, cuisine. And, starting in the late 1960s, Dovecrest became the home of Red Wing (Mary E. Congdon, 1896-1897), a very prominent storyteller and keeper of cultural knowledge for the Narragansett-Niantic and Wampanoag Tribes. When Red Wing moved in, she brought with her the contents of the first Tomaquag Museum, and reestablished the museum at Dovecrest. Today, the restaurant is no more, but the Tomaquag Museum is still there, at the old Dovecrest location. Soon, southeastern Connecticut will have a local Indigenous restaurant / community space / educational facility, too. Chef Sherry Pocknett, who was featured in a Time Magazine article earlier this week (link in the sources below), is a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Nation who is currently raising funds for a new facility on the Poquetanuck Bay in Preston, Connecticut. It will be called Sly Fox Den, and the full plan involves not just a Native cuisine restaurant and bar, but also an “Indigenous Native American Living Museum and Oyster Farm” which will include traditional Wampanoag buildings and gardens, an outdoor cooking area, an oyster farm, and live demonstrations of traditional Wampanoag tradecrafts like canoe-making. While funds are being raised for the primary Connecticut site, Chef Sherry Pocknett has opened another restaurant in Charlestown, Rhode Island — Sly Fox Den Too. Perhaps remembering the Narragansett Dovecrest Restaurant of decades past, the local Narragansett community around Charlestown graciously welcomed Chef Sherry Pocknett and her Wampanoag family when she opened the restaurant in the summer of 2021. Certainly, there is a history of immeasurable injustice committed by English colonists (and later “Americans”) to the Native peoples of this country, and it is vital that that history be shared, discussed, and addressed. But it is just as important to tell and celebrate the stories of Native resilience and accomplishments — from times past up to the present. While we eagerly wait for the opening of the primary Sly Fox Den in Connecticut, we share the following excerpt about their spiritual predecessor: Dovecrest Restaurant. To read the whole piece, find the original at the Tomaquag Museum’s blog Belongings. Check the source below the excerpt for the link to the full blog post, which includes additional details on the Dove family, Red Wing, the thanksgiving celebrations at Dovecrest, and more. On the Belongings blog page, you will also find four special Indigenous recipes! —

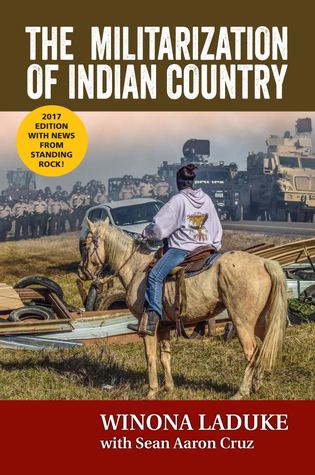

…Initially, when the Doves had opened Dovecrest Restaurant the menu offered “standard steakhouse fare,” which was typically considered main dishes such as beef steaks, pork chops chicken and seafood with sides of vegetables and hearty soups, stews and chowders- your typical Yankee style meat and potatoes type restaurant. (This was very much the backbone of the Dovecrest Restaurant for its entire existence.) It wasn’t until a few years after Dovecrest was in operation that patrons of the restaurant noticed that the Doves were preparing different meals for their children in the room behind the kitchen. These meals comprised of wild meats, or “game” meats. Soon, customers were asking that if instead of ordering the standard steakhouse fare, they were able to order dishes such as venison stew and creamed dried cod. Venison was of course an important staple for the Indigenous people throughout time on both the North and South American continents. Venison was essential to both survival and culture as the white tailed deer provided not only food, but clothing, adornments and tools. Ferris, in his own words, “When I was growing up in Charlestown, we depended on food like venison. We would have feasts of venison steaks, oysters we pulled from the bay, Johnnycakes and potatoes. This was 1930, and only the poor people were eating that stuff. Now it’s a delicacy. Isn’t it funny how things change?” And things did change. Slowly, but surely the Doves began incorporating wild game and other traditional Indigenous recipes, some that Eleanor had learned from her father, Joseph Spears, Sr. (who had also been a chef at the University Club in Providence) into the menu. These wild games were then appeared on for special occasions or whenever wild game or shellfish happened to be available and/or in season. Eleanor said she tried to always keep one game dish on the menu, but it was often difficult to have a steady stock on hand. Many of the wild game was procured locally, from friends and neighbors who hunted, but for other types of game, such as bison they had to rely on private, out of state distributors such as ranch in Western Massachusetts or Iron Gate Products in Manhattan. As the specialty wild game dishes began appearing on the menu, word traveled fast and Dovecrest started to become well known as a restaurant that was not only owned and operated by Indigenous people-at that time the only such establishment east of the Mississippi River-but Indigenous people who were also serving traditional Indigenous foods in this small, out of the way place in rural Exeter. One of the dishes which became a specialty at Dovecrest was a “briny fresh clam chowder” which were of course locally sourced from Narragansett Bay and other locations in Rhode Island and were shucked by Ferris every Friday and according to Eleanor “does it faster than anyone I’ve ever seen.” In addition to the venison stew, creamed dried cod and briny; or Rhode Island style clam chowder, Dovecrest entrees on the menu could include bison steak and pie, quahog pie, venison steak and pie, rabbit stew, squirrel pie, racoon pie, bear, elk, succotash, Indian pudding-and what they became most famous for, Johnnycakes. Johnnycakes, or “Journey cakes” as they were known during the contact (Colonial) period, were a traditional staple of Indigenous people throughout North America and the Caribbean before the invasion of Europeans and was quickly adopted by European colonists and anglicized into what we know now as Johnnycakes. Usually (but not always) they are made out of ground white flint maize, water, milk and butter, salted with a little sugar and cooked on a griddle until deep golden brown, Johnnycakes then became a staple of European colonial life and like many of the plants and animals in the Americas slowly had their Indigenous roots erased through time. Johnnycakes were served plain, as is, or with additional local, seasonal ingredients such as maple syrup, blueberries and cranberries. Over the years as their reputation grew, Dovecrest Restaurant was recognized in many ‘Best of” guides, winning rave reviews for their Johnnycakes as often the best in the state (and even some said New England) appearing in a New York Times article ‘Cuisine as American as Raccoon Pie’ in December 9, 1981 and even winning a 1982 Ocean Spray Cranberry Salute to American Food Award in Pittsburgh in addition to a USA Today article, ‘On The Menu Succotash and Venison.’ All of the awards and accolades were hard earned and well deserved for Dovecrest Restaurant, especially the Dove matriarch Eleanor, who was the primary chef and ran the kitchen. According to Ferris, “she’s the cook and I’m the waiter.” In addition to Ferris’ clam shucking, bartending and wait duties, Dovecrest Restaurant and Trading Post was a family operation and relied on the help of close family members such as their children, Mark, Paulla, Dawn and Lori and later granddaughters Elisabeth Dove (Manning) and Lorén Wilson (Spears) as well as Eleanor’s father Joseph Spears, Jr. and Ferris’ mother Mimi Babcock Dove as well as other extended family members and local tribal members… — Take Action See how you can support the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative: http://www.narragansettfoodsovereignty.org/ Donate to the Sly Fox Den project here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/sly-fox-den-restaurant-and-bar — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources “From the Archives: Dovecrest Restaurant & Thanksgiving.” Tomaquag Museum. 26 November 2020 [Accessed 17 November 2021]. https://www.tomaquagmuseum.org/belongingsblog/2020/11/2/dovecrest-restaurant-and-thanksgiving Burns-Fusaro, Nancy. “Indigenously Delicious: Sly Fox Den Too opens in Charlestown.” The Westerly Sun, 21 July 2021. https://www.thewesterlysun.com/news/charlestown/indigenously-delicious-sly-fox-den-too-opens-in-charlestown/article_5bd5e3be-e4be-11eb-8294-c7f7dce648e1.html “Our Mission.” Sly Fox Den Restaurant. https://slyfoxdenrestaurant.com/our-mission Waxman, Olivia B. “Her Tribe Fed the Pilgrims. Here’s What She Wants You to Know About Indigenous Food.” Time Magazine, 15 November 2022. https://time.com/6233957/indigenous-chef-thanksgiving-pilgrims/ — Further Resources Here is a podcast episode for all ages about Wampanoag and Narragansett thanksgiving traditions featuring Loren M. Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum: “Giving Thanks!” Time For Lunch podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/giving-thanks/id1504928110?i=1000499993371 For Veterans Day, we again share excerpts from Winona LaDuke’s 2013 book The Militarization of Indian Country. We want to help shine light on the connections between the US military and many issues (past and current) that affect Native communities in the United States. The relationship between the US military and Native Americans is complex, but also clearly unequal and abusive. From her research, LaDuke tells story after story of the US military’s rapacious exploitation and consistent denigration of Native individuals, communities, and lands — a colonialist project that continues to this day. Little has changed in Native affairs since last November, and so we are posting these excerpts again this year. Winona LaDuke is a Native American Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) activist-economist who is known for her involvement in many large Native projects: the White Earth Land Recovery Project, which reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people (including Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm); Honor the Earth, a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues; and most recently, the Line 3 pipeline protests that seek to prevent enormous ecological disasters in Native lands. Following the whirlwind of political activism that brought down statues of slave owners, Columbus, and other colonizers in the last few years, many of these campaigns that did not resolve quickly have either become mired in bureaucratic purgatory or sputtered out altogether — the statue of John Mason, now-infamous leader of the Mystic Massacre, still stands at the Capitol in Hartford. Line 3 construction continues, as does Native resistance to it. The exploitation of Native peoples, present and past, goes on unabated. As LaDuke recently put it in an article for InForum: “Stop the Indian wars, and make new history.” (See below for the excerpts from The Militarization of Indian Country) — [...]

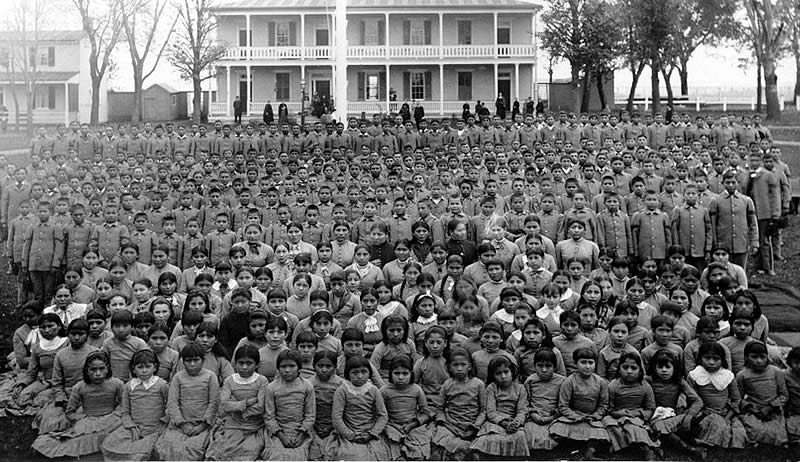

I do not hate the military. I do despise militarization and its impacts on men, women, children, and the land. The chilling facts are that the United States is the largest purveyor of weapons in the world, and that millions of people have no land, food, homes, clean air or water, and often, limbs, because of the military funded by my tax dollars. Countless thousands of square miles of Mother Earth are already contaminated, bombed, poisoned, scorched, gassed, bombarded, rocketed, strafed, torpedoed, defoliated, land-mined, strip-mined, made radioactive and uninhabitable. I despise militarization because those who are most likely to be impacted or killed by the military are civilian non-combatants. Since the Second World War, more than four fifths of the people killed in war have been civilians. Globally there are some 16 million refugees from war… I decided to write this book because I am awed by the impact of the military on the world and on Native America. It is pervasive. Native people have seen our communities, lands and life ways destroyed by the military. Since the first European colonizers arrived, the US military has been a blunt instrument of genocide, carrying out policies of removal and extermination against Native Peoples. Following the Indian Wars, we experienced the forced assimilation of boarding schools, which were founded by an army colonel, Richard Pratt, and which left a history of transformative loss of language and culture. The modern US military has taken our lands for bombing exercises and military bases, and for the experimentation and storage of the deadliest chemical agents and toxins known to mankind. Today, the military continues to bomb Native Hawaiian lands, from Makua to the Big Island, destroying life. The military has named us and claimed us. Many of our tribal communities are named after the forts that once held our people captive, and in today’s military nomenclature Osama bin Laden, the recently killed leader of al Qaeda, was also known as “Geronimo EKIA” (Enemy Killed in Action). Harlan Geronimo, an army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam and is the great grandson of Apache Chief Geronimo, asked for a formal apology and called the Pentagon’s decision to use the code name Geronimo in the raid that ended with al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden’s death, a “grievous insult.” He was joined by most major Native American organizations in calling for a retraction and apology. The Onondaga nation stated, “This continues to personify the original peoples of North America as enemies and savages. . . . The US military leadership should have known better.” The analogy from a military perspective is interesting. At the time of the hunting down of Geronimo, over 5,500 military personnel were engaged in a 13-year pursuit of the Apache Chief. Geronimo traveled with his community, including 35 men and 108 women and children, who in the end surrendered in exhaustion and were met with promises that were never fulfilled. It was one of the most expensive and shameful of the Indian Wars… The military, it seems, is comfortable with this ground. Indeed, Native nomenclature in the US military is widespread. From Kiowa, Apache Longbow and Black Hawk helicopters to Tomahawk missiles, the machinery of war has many Native names. (The Huey helicopter―Bell UH-1 is the Iroquois, and the Sikorsky helicopters are also known as Chickasaw, Choctaw and Mohave helicopters.) As the Seventh Cavalry invaded Iraq in 2003 in the “Shock and Awe” campaign that opened the war, one could not help note that this was the name of the cavalry division that had murdered 300 men, women and children at Wounded Knee. Yet, despite our history and the present appropriation of our lands and culture by the military, we have the highest rate of military enlistment of any ethnic group in the United States. We also have the largest number of living veterans out of any community in the country. We have borne a huge burden of post traumatic stress disorder among our veterans, and continue to feel this pain today, compounded by our own unresolved historic grief stemming from colonization. In this book, I consider the scope of our historic and present relationship with the military and discuss economic, ecological and psychological impacts. I then examine the potential for a major transformation from the US military economy that today controls much of Indian Country to a new community-centered model that values our Native cultures and traditions and honors our Mother Earth… — Take Action Sign the petition and see what else you can do to stop Line 3 and support Water Protectors: https://www.stopline3.org/biden While on the topic of Indigenous issues, there is a renewed campaign to free Native American activist Leonard Peltier from prison. Read about his story and, if you are moved to do so, support the Leonard Peltier Freedom Ride 2021 — Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust — Sources LaDuke, Winona. The Militarization of Indian Country. Michigan University Press, 2012. LaDuke, Winona. “LaDuke: Stop the Indian wars, and make new history.” InForum. 28 September 2022. https://www.inforum.com/opinion/columns/laduke-stop-the-indian-wars-and-make-new-history — Further Resources Honor the Earth: a Native arts and culture organization meant to support Indigenous communities and environmental issues. https://www.honorearth.org/ White Earth Land Recovery Project: reclaims Anishinaabe reservation land for the economic development of Anishinaabe people. https://www.welrp.org/ The following piece was originally posted in November 2020 to explain how American prejudices and historical ignorance has led to extermination campaigns of Native peoples, how American racist policies directly inspired Nazi practices, and how those ideas continue to influence American society and threaten minority groups. As we roll into Election Day next week, consider sharing this piece to start conversations and educate people on the topic. The following has been lightly edited from the original.

— November is Native American Heritage Month, and Thanksgiving is just one week away. While Thanksgiving is a holiday fraught with a problematic history, it is also ostensibly a day to thank Native American contributions to the history of the United States. But of course, many of us are canceling Thanksgiving plans this year to keep our families safe as the covid-19 pandemic surges across the country. And with President Trump still refusing to concede the election and instead continuing to promote baseless conspiracy theories, some might think that it is a mistake to focus so much attention on the social representation of a small minority population at such a crucial time. A lack of accurate, positive representation leads to a reliance on easily manipulable and usually negative stereotypes, which in turn leads to the systematic dehumanization of the minority group. Combined with other societal narratives of “natural” entitlement and being threatened on all sides, this deadly mix has historically led to genocides. Indeed, both the means and the reasons used by the Nazis to perpetrate ethnic cleansing in Eastern Europe were inspired by the American conquest, cleansing, and forced resettlement of the American Indians of the Western United States. During the “Indian Wars” between 1846 and 1890, the U.S. massacred countless Native peoples and forced the rest onto “reservations” of unwanted tracts of land in order to open up desirable land for settlers. One way or another, Native peoples were expected by white Americans to be “eliminated” or else to “disappear” on their own. Not too long ago, these atrocities were celebrated as advancements in human progress, not just in the United States, but in Nazi Germany. According to Carroll P. Kakel, III, Hitler conceived of the German war in Eastern Europe as a colonizing war of ethnic cleansing to remove Slavic and Jewish peoples to make way for lebensraum, “living space” for Germans. Hitler himself encouraged his close associates to “look upon the natives [of Eastern Europe] as ‘Redskins’” of the American West. If the endgoal of both colonial wars was the removal of the Other to make space for white or German settlers, then the concentration camps of the Holocaust can be seen as an upgraded, more efficient Native reservation. Of course, the entire process of conquering and destroying Native peoples in the American West was just a small part of the massive racist project in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. James Q. Whitman has pointed out that Nazi Germany repeatedly found inspiration in restrictive American racial laws, not only with respect to Black Americans, but with all other non-“nordic” peoples. In fact, in the early 20th century, the United States led the world in racist law -- at least in the eyes of the Germans, Brazilians, Australians, and South Africans who implemented infamously racial codes in their own countries modeled after the American ones. As Whitman points out, Nazis themselves had a difficult time finding other models for racist codes like anti-miscegenation laws, except in the case of the “classic model” of the United States, where there was a robust tradition of forced segregation, restrictive racial immigration quotas, and second-class citizenship. Perhaps it is shocking to learn that the Nazis themselves were inspired by the American treatment of Indigenous, Black, and other non-white peoples. Most Americans do not associate the United States with fascism or Nazism -- we fought them, after all, didn’t we? Some have heard that prominent American figures like Henry Ford and Walt Disney were Nazi sympathizers before the attack on Pearl Harbor, but generally consider such information as curious details of eccentric tycoons during “a different time” in history. Some have even heard of the American Nazi rally in 1939 that attracted more than 20,000 people to Madison Square Garden. But most Americans would likely deny that any genocides have ever occurred in the United States -- not out of denialism, but out of historical misunderstanding and confusion about what genocides actually are. But then there are also those who believe in the “white genocide” myth, or the “Great Replacement” variation. The conspiracy theory is shockingly popular in some form or another among white conservatives and reveals the anxieties over ethnic diversity and the atrocities committed upon People of Color. Those who believe the “white genocide” myth fear that, given the chance, African-Americans would start a race war to exterminate white people out of revenge for slavery, disenfranchisement, terror, and more. The “Great Replacement” idea is more subtle, stating that unending waves of immigration into Western countries like the United States will lead to the rapid growth and spread of non-white people, ultimately ending in the “replacement” and erasure of whiteness and Western culture. Both of these variations often point to some shadowy group directing these massive demographic shifts specifically to exterminate white people. Strangely, these imaginary “globalist” or “New World Order” groups are usually composed of Jewish people. The United Nations defines “genocide” as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

Since there is no secret group imposing such policies on “white people” generally, and Black Americans time and again have faced violence with resolute nonviolent action. Those conspiracy theories are pure fantasy, but even entertaining them can be dangerous. If the precieved threat is as existential as death, replacement, and erasure, then the logic of those fantasies must always end with a kind of preemptive genocide or other atrocity to “protect” the “white race.” This is exactly the logic that led many ordinary Germans to look away from the worst atrocities their government committed upon Jewish, Slavic, and other peoples. It’s the logic that excuses separating children from their parents and locking them in cages today. It’s the logic that makes a threat out of any Black man, and what lets their murderers escape justice time and again. The online series The Man in the High Castle, based on the novel by Philip K. Dick, takes place in an alternate 1960s in which the Axis powers won the Second World War. At one point in the series, a white asylum seeker studies with a Hitler Youth to become a naturalized citizen of The Greater Reich, which spans most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. As they study, the Hitler Youth brings up a question “about American exterminations before the Reich.” The asylum seeker asks with confusion, “exterminations?” to which the Hitler Youth replies almost with amusement: “Didn’t they ever teach you about the Indians?” Let’s just make sure we get the story straight. — Sources and Further Reading: Cochran, David Carroll. “How Hitler found his blueprint for a German empire by looking to the American West.” Waging Nonviolence, 7 October 2020. https://wagingnonviolence.org/2020/10/hitler-found-blueprint-german-empire-in-the-american-west/ “Genocide.” United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide.shtml Kakel, Carroll P. The American West and the Nazi East: A Comparative and Interpretive Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Schwartzburg, Rosa. “No, There Isn’t a White Genocide.” Jacobin, 4 September 2019. https://jacobinmag.com/2019/09/white-genocide-great-replacement-theory Whitman, James Q. Hitler's American Model: the United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press, 2018. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed