|

On July 25, 1898, the United States invaded Puerto Rico and recolonized the island nation, just one week after Puerto Ricans had established a semi-independent government from Spain. For the past 123 years, the United States has held possession of Puerto Rico as a colony in various forms; the official euphemism currently in use is “commonwealth.” Puerto Ricans on the island today are subject to federal laws, eligible for the draft, and technically hold US citizenship — but cannot vote in federal elections, have limited access to certain government services, and are not permitted to control their own trade policy. But to understand why some have called Puerto Rico “the oldest colony in the world,” we must first examine the history of the US-PR relationship.

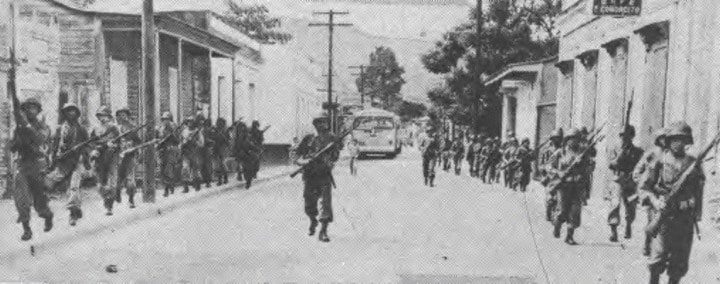

Before the 1898 invasion, the island of Puerto Rico had a centuries-long history as a colony of the Spanish Empire, a longer history of indigenous Taino cultural hegemony before the Spanish, and an even longer history of periodic migration waves from South America before the emergence of the Taino culture. But by the mid to late 19th century, international affairs had changed drastically from previous eras. The success of independence movements across the Americas had reduced the Spanish Empire to a shadow of its former self. With Cuba and Puerto Rico as the last remaining crown jewels left in the Spanish “New World,” and a new ascendant ideology emphasizing the importance of naval supremacy, the Spanish Empire was desperate to do whatever they could to keep the two large Caribbean islands — including granting concessions to the residents. By 1898, Puerto Rico was on a path to independence from Spain: Puerto Ricans won the abolition of slavery after the 1868 Grito de Lares uprising, adopted a national flag after the 1897 Intentona de Yauco uprising, and in the same year convinced the Spanish government to grant limited self-government including a partially-elected bicameral legislature. On July 17, 1898, the new Puerto Rican government began operating. Eight days later, as part of the Spanish-American War, the United States invaded the island and ended the PR self-rule experiment before it had a chance to prove itself. In the two years following the invasion and the end of Spanish-American War, the United States ruled Puerto Rico by a military government, which was replaced by a civilian government largely appointed by the US government. Over the next five decades, Puerto Ricans struggled against US rule at every level, trying to establish self-governance on the island. During this period, the US government adopted the Jones Act which reformed both houses of the PR legislature to a fully democratic system and granted US citizenship and the attending Constitutional rights to Puerto Rican residents. But the Jones Act also made Puerto Ricans eligible for military conscription just as the United States was preparing to join the First World War — indeed, the PR legislature unanimously rejected the Jones Act for this very reason, but was overruled by the US government. For three decades after the Jones Act, Puerto Ricans would suffer heavily from a major earthquake, a tsunami, several hurricanes, the effects of the Great Depression, and perennially insufficient aid from the United States. Many Puerto Ricans were also killed or injured while protesting the clearly exploitative relationship with the United States, most notably in the Ponce Massacre in 1937 in which the US-controlled Insular Police killed 19 people and injured 200 more at an unarmed protest. Prompted by the demonstrations in Puerto Rico, US Senator Millard Tydings unsuccessfully attempted to pass bills for PR independence twice in this period. It was only in 1948 that Puerto Ricans were finally able to vote for their own governor. But that same year, the Puerto Rican Senate passed the infamous Law 53 AKA the Gag Law which imposed heavy prison sentences and fines and suspended Constitutional rights for those found to promote Puerto Rican independence and/or nationalism. This move unofficially cemented Luis Muñoz Marín, one of the US government’s major political allies on the island, as the premier politician in Puerto Rico. By this point, US banks owned about half of the arable land and many other railroads and harbors in Puerto Rico, and the United States government was motivated to protect those investments. In 1950, when nationalists led a revolt against the drafting of what they considered a new colonial constitution, the United States responded by deploying 4000 troops, 10 fighter planes, and several 500-pound bombs. US Armed Forces destroyed much of the Jayuya and Utuado municipalities, killed and wounded dozens, and imprisoned and tortured nationalists in secret prisons for over a decade afterward. Over the 1950s and 1960s, the United States government with the help of Muñoz Marín began Operation Bootstrap to accelerate the economic colonization of the island. The plan under Operation Bootstrap offered tax exemptions for US businesses, which siphoned much-needed revenue from public necessities like schools, roads, and hospitals. The traditionally agrarian society transformed into an industrial one very rapidly, with wages increasing for many who could get work in the new industries. But the new economy could not support as many workers as the old one and so unemployment rates dramatically increased. In an effort to sustain this new economy, Muñoz Marín and the United States government encouraged the unemployed to emigrate to the United States mainland. Nearly half a million Puerto Ricans moved to US cities, most notably to New York City where they became known as “Nuyoricans.” In another attempt to limit the PR population, Muñoz Marín and the US government also conducted coerced sterilization programs, which were so effective that, according to one scholar, over ⅓ of all Puerto Rican women of child-bearing age had been sterilized by 1969. By 1970, Luis Muñoz Marín had retired from politics, but the economic system he had helped to engineer would continue to accelerate over the next few decades. With Operation Bootstrap, Puerto Rico was much more thoroughly integrated into the American economy, making exploitation even easier. The island would never be the same again. When we return to this story of the recolonization of Puerto Rico in a few weeks, we will examine the more recent troubles the island has faced, as well as some ways that Puerto Ricans have come together to support each other, to overcome (or at least cope with) many recent hardships, and to forge a new path for the island and its people. -- Support Us We commit a significant amount of research and writing to produce A Peace of History each week. If you like our weekly posts, please consider supporting this project with a one-time or recurring donation. Your gift will be used to continue producing more A Peace of History posts as well as the greater mission of VPT. You may type in however much you would like to give; contributions of all sizes are appreciated. Click this link to learn more about what we do and how you can donate: https://www.mightycause.com/organization/Voluntown-Peace-Trust -- Sources Cheatham, Amelia. “Puerto Rico: A U.S. Territory in Crisis.” Council on Foreign Relations. 25 November 2020 [Accessed 21 July 2021]. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/puerto-rico-us-territory-crisis Darder, Antonia. “Colonized Wombs? Reproduction Rights and Puerto Rican Women.” The Public i. December 2006 [Accessed 21 July 2021]. http://publici.ucimc.org/2006/12/colonized-wombs-reproduction-rights-and-puerto-rican-women/ Guisado, Angelo. “It’s Time to Talk About Cuba. And Puerto Rico, Too.” Current Affairs. 15 October 2020 [Accessed 21 July 2021]. https://www.currentaffairs.org/2020/10/its-time-to-talk-about-cuba-and-puerto-rico-too Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed